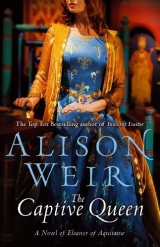

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

42

42

Argentan, 1171

Unable to bear the tension, the King abandoned the Yuletide festivities, dismissed his guests, and left with the Queen for Argentan. It was there that Brother Peter, a young monk from England, mud-spattered and exhausted from a hard ride, found him, just as he and Eleanor were entertaining Bishop Arnulf of Lisieux to supper in their private solar.

“Lord King,” the monk gasped, falling to his knees for sheer weariness. “I bring terrible news.”

Henry went white and clenched his knuckles. The bishop leaped up, scraping back his chair.

“What news?” Eleanor asked sharply.

“My lady, Archbishop Becket has been murdered, slain in his own cathedral two days ago, as he celebrated Vespers.”

Eleanor was momentarily speechless, unable to take in the enormity of what she had just heard. “Murdered?” she repeated stupidly. “The Archbishop of Canterbury?”

“He was cruelly slain by four of the King’s knights,” Brother Peter said, himself deeply distressed.

“Oh, God!” Henry wailed suddenly, beating his breast. “Thomas, my Thomas! May God forgive me—this is my doing. I have killed him, as surely as if I strangled him with my own hands.” Tears were streaming down his face and great sobs racking his stocky frame.

“May God avenge him,” the bishop murmured, crossing himself, appalled to the very core. “This is surely the worst atrocity I have ever heard of. It is unbelievable that anyone should commit such sacrilege as to slay an archbishop in the house of God.”

Henry turned a ravaged face to him. “It was done for me, at my behest. I am to blame. But as God is my witness, I lovedThomas, in spite of our quarrel. I spoke those words in anger. I did not mean them to be taken literally. I loved him!” His words were coming between short breaths; he was almost too paralyzed by shock to say more, and the bishop was staring at him, not quite comprehending what he was talking about. Eleanor went swiftly to Henry and would have comforted him, but he turned his back on her. “No—I am not worthy of consolation,” he wept bitterly. “Leave me to my terrible grief.”

She felt a pang of anguish at being rejected but thrust it away, realizing that Henry needed time to come to terms with what had happened. This was a matter for his confessor, not his wife, although in time he might come to confide in her. For now, she turned her attention to the poor, shivering monk, and herself poured him a goblet of wine. She also handed one to the weeping bishop, who gulped it back gratefully, then she offered another to Henry, but he was too distraught to notice.

“Now,” she said to Brother Peter, “please sit down and tell us everything that has happened.”

The young man did as he was bid, and piece by piece the whole tragic story came out. How Becket had gone back to England and, after all his fair words, defiantly excommunicated those bishops who had taken part in the coronation of the Young King. How the four knights turned up at Canterbury and threatened the Archbishop with dire punishment if he did not immediately leave the kingdom. How Becket calmly told them to stop their threats, as he was not going anywhere, and sent them away.

“All afternoon they were hanging around the courtyard, plotting together, shouting insults about His Grace to us monks, and putting on their armor,” Brother Peter related. Once he had overcome his initial diffidence and mastered his distress, the words had come tumbling out. “Then, when we proceeded into the cathedral for Vespers, they followed us almost to the very doors. Truly, sirs and lady, we were terrified. When His Grace the Archbishop entered the church, we stopped the service and ran to him, thanking God to see him safe, and we hastened to bolt the doors, to protect our shepherd from harm. But”—and the homely peasant face crumpled at the memory—“he bid us throw them open, saying it was not meet to make a fortress of the house of prayer, the church of Christ. And it was at that moment that the four knights burst in, with drawn swords …” Brother Peter could not go on.

“Take your time,” Eleanor soothed, offering him more wine, and some bread to soak it up. She was horrified at what she was hearing, but still in control of her emotions. The time for weeping would come later, but with Henry seemingly in a stupor, still standing with his back to them, while intermittently emitting pitiful groans and cries, and Bishop Arnulf awash with tears, someone had to remain in control.

“I must tell it all,” Brother Peter sniffed. “The world must know of this terrible deed.”

“We are listening,” Eleanor told him. “And you may rest assured that justice will be done.” She saw Henry flinch.

“We were that frightened when we saw the devilish faces of those knights and heard the clanging of their arms,” the monk continued. “Everyone was watching in horror—all save His Grace. He were calm, and when the knights asked where was Thomas Becket, that he was a traitor to his king, he answered, ‘I am here, no traitor, but a priest.’ There was no fear in him. He asked why they sought him, then he told them he were ready to suffer in the name of his Redeemer. And he were that brave—he actually turned away and began praying!”

Eleanor held her breath as the monk paused, forced himself to chew on some bread, for which he clearly had little appetite, and went on with his tale.

“The knights came forward. They demanded that he absolve the bishops he’d excommunicated, but he refused. ‘Then you shall die!’ they said. I will never forget those words. His Grace just looked at them, and told them he were ready to die for the Lord Jesus, so that, in his blood, the Church might find liberty and peace. They didn’t like the idea of him being a martyr, so they tried to drag him outside, laying sacrilegious hands on him. But he resisted, accusing them of acting like madmen, and fell to prayer. Then one knight raised his sword and smote him on the head, drawing blood. Brother Edward ran forward and tried to save His Grace, but they near sliced his arm off. Then it all happened very quickly. My lord was clinging to a pillar, and they hit him again on the head, but still he stood there. They struck him a third time, and he was bleeding badly when he fell on his hands and knees, calling us to witness that he was willing to embrace death for the sake of the Lord Jesus and the Church. He lay there on the paving stones; he were still alive and conscious, and then one of those devils went for him again, and sliced up the top of His Grace’s skull with such force that the sword broke. He spilled his blood and his brains all over the floor, defiling our holy cathedral. It was the worst thing I have ever seen in my life. Then the knights scattered, and we were left to minister to the poor Archbishop, who was then beyond mortal help. He’d embraced his martyrdom with powerful courage, and truly, as I do believe, his blissful soul is with God.”

There was an appalled silence in the solar as Brother Peter fell silent. Then the King emitted a strangled sound, as the bishop wiped his eyes on his sleeve.

“This surpasses the wickedness of Nero,” Arnulf pronounced. “Even Herod was not as cruel.”

“May God rest Archbishop Thomas,” Eleanor said. She was shocked by his murder, and shocked too to find herself wondering if it had been yet another of Becket’s dramatic gestures. It seemed he had almost welcomed martyrdom, had gone out of his way to court it. Yes, that would have appealed to his vanity! It would certainly have been the ultimate revenge on Henry …

Aghast at what she was contemplating, for it was unthinkable that she should be so uncharitable in the face of the terrible fate that had befallen Becket, she stood up, summoned the steward to arrange a bed and some food for Brother Peter, made it courteously clear to the bishop that it was time for him to leave, and then, when they were finally alone, turned her attention to her husband.

Henry was like a broken puppet, his movements jerky and uncoordinated, his breathing ragged. Wrapped in his torment, he did not resist as she led him to the bed and herself stripped off his tunic and hose. Recumbent, he lay there with his face working in distress, moaning and sobbing. When she tried to hold him, he shook her off again. There was no reaching him.

Rapidly, the dread news spread throughout Christendom. The whole world was—like Henry—in shock. The murder was unanimously condemned as being equal in iniquity to Judas’s betrayal of Christ, and King Louis loudly demanded that the Pope unleash the sword of St. Peter in unprecedented retribution. Everywhere, Becket was hailed unreservedly as a blessed martyr, and universally, people laid the blame for his killing at the door of the King of England.

“In truth, Becket is more powerful dead than he was alive,” Eleanor complained to her son Richard, as they listened to yet another tale of the good people of Canterbury flocking to the desecrated cathedral to smear themselves with the blood of their slaughtered archbishop, or to snip pieces from his stained vestments as relics. “Soon, they will be claiming that miracles are taking place at his tomb!”

“I heard him called ‘God’s doughty champion’,” the boy said. “His murder was a terrible thing, but people now forget his long disobedience to his king.”

“It is your father who is the villain now,” Eleanor observed bitterly. “I fear his fame will never recover. And the tragic thing is that he loved Becket, right to the end. He had no real wish to do him harm. And that, my son, is why you should always check yourself before uttering words in anger, words you do not really mean. Had your father done so, Becket would be alive today.”

Henry remained in seclusion for six weeks, refusing to attend to the business of ruling his vast domains. Shut away from the world, he put on a rough robe of sackcloth that he had smeared with ashes from the fire, in penitence for his terrible sin, although nothing, he was convinced, could ever truly expiate it. For three days he took no food, nor would he admit anyone to his chamber—not even his anxious wife. Soon, Eleanor was beginning to wonder if he had lost his reason; she even began to fear he might take his own life. It also occurred to her, although she begged God to forgive her for thinking it, that he was feigning such excessive grief in order to convince people that he could not possibly have desired Becket’s death.

In desperation, she summoned the Archbishop of Rouen, begging him to offer her husband some spiritual comfort.

“The King spoke quite lucidly to me,” the Archbishop told Eleanor after being closeted with Henry for some time. “He is not going mad, so you may put your mind at rest on that score. But he is suffering from an excess of remorse. He holds himself entirely responsible for Archbishop Becket’s murder, even though it had not been his desire or intent. Yet he knows he has brought upon himself the censure and condemnation of the whole of Christendom, and in my presence he called upon God to witness, for the sake of his soul, that the evil deed had not been committed by his will, nor with his knowledge, nor by his plan.”

“I believe that to be true,” the Queen said. “I know him well, and I was there. I heard him say those words. They were spoken in the heat of the moment. Devious and quarrelsome he may be, a tyrant and murderer never.”

“You speak truth,” he replied. “The hard part will be convincing the rest of the world of it. But the King your lord has willingly agreed to submit, through me, to the judgment of the Church, and, showing great humility, he has promised to undertake whatever penance she should decide upon.”

“What more can he do?” Eleanor asked despairingly.

“What of the murderers, those satellites of Satan? Is there any news?”

“They have disappeared, by all reports, although I have ordered the King’s officers in England to make a thorough search.”

“They are dead men already, or as good as,” the Archbishop commented acidly. “The Pope will certainly excommunicate them.”

“I pray he will not excommunicate my lord the King also,” Eleanor said.

“I hope not. The King has decided to send envoys to His Holiness, who will protest that he had never desired the sainted Becket’s death.”

“Alas, I fear that His Holiness will heed the general opinion, which is much to the contrary,” Eleanor worried. Waiting for the Pope to speak would be like having the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads.

Underlying her fear was anger. Henry was a great king; he did not deserve such calumny. Even in death, Becket was hounding him.

Eventually, Henry emerged from his long seclusion, thinner and aged by several years. He had recovered his composure, though, and was ready to take up the burdens and cares of government, but was still weighed down by remorse. Grief and guilt were eating at him, and made him short-tempered and difficult to live with.

Eleanor might have been a distant stranger. Henry had rejected all her offers of comfort in the time of his direst need, and he had nothing to give her now, nor did he appear to want even her companionship. He had withdrawn into himself, his emotions drained. With her fledgling hopes of a permanent reconciliation dashed, she felt that she had little to offer him, and that it might be better for both of them if she were to return to Aquitaine, at least for a short time. Maybe her absence would work its magic, as before. She was not surprised when Henry agreed to her going without protest.

“You are needed there,” was all he said.

As soon as the weather improved, and the roads were passable, she made her farewells, told Henry that he could be assured of her prayers, for the Pope had not yet spoken, and reluctantly rode south.

43

43

Limoges, 1172

Eleanor thought it was a great pity that Henry was not here to see Richard invested as Duke of Aquitaine. The sight of his fine, strapping son in his silk tunic and gold coronet, enthroned in the Abbey of St. Martial, would surely have gladdened his sad heart. It was a shame to be here alone, enjoying this triumph all by herself, watching the abbot place the ring of the martyred St. Valérie, the patron saint of Limoges, on the boy’s finger, and then hearing him proclaimed Duke, as he was presented to the cheering people of Limoges. And thank God they werecheering, she thought; it was as if they were aware that this ceremony, which she herself had devised, was a means of making a final reparation to them for tearing down their walls all those years before.

They had been in agreement, Henry and Eleanor, that Richard, now fourteen, was old enough to exercise power in Aquitaine as its ruler, although she herself, as sovereign duchess, would remain at hand to advise and assist him; they would govern her domains in association with each other—just as they had recently laid the foundation stone together for a new abbey dedicated to St. Augustine.

Richard was now taller than his father and showing signs of becoming a graceful, muscular man, with his long limbs and commanding appearance. In features, he resembled Eleanor, although he got his piercing gray eyes from Henry.

“The Young King is a shield, but Richard is a hammer,” Raoul de Faye perspicaciously declared as they walked in the cloisters taking the late evening air after the feasting had ended. “He will succeed at whatever enterprise he attempts.”

“He is single-minded enough to do so.” Eleanor smiled, knowing that once her son’s mind was made up, he was immovable—just like Henry. “Of all my sons, he is the one destined for greatness.”

“I am impressed to see how he reposes all his trust in you,” Raoul said. “Already, he strives in all things to bring glory to your name.”

“I am much blessed in Richard’s devotion,” she replied proudly. “He is inexpressibly dear to me. I am so sorry that Henry could not be here to witness this day, but he is busy in Normandy. At least he has made his peace with the Pope.” It had taken an oath, sworn by Henry in Avranches Cathedral, that he had neither wished for nor ordered the killing of Becket, but had unwittingly and in anger uttered words that prompted in the four knights the desire to avenge him.

Eleanor could only imagine what it had cost Henry to make this public confession, humiliating in the extreme for a proud man such as he. Maybe being formally absolved of the murder by the Archbishop of Rouen had helped to alleviate his guilt and remorse, but it came at a price. She had winced when they told her how the King, wearing only a hair shirt, submitted to the shame of a public flogging by monks, in the presence of the Young King and the papal legate. It was not the most edifying example for a father to present to his son, still less for a king to show his subjects—and yet she knew it had been a necessary gesture. She still shuddered to think how painful a penance this must have been for Henry, in every way, and could have wept for the bloody lacerations inflicted by the whips and the hair shirt, and for the deeper wounds to her husband’s soul.

Yet still, it seemed, God, the Church, and the ghost of Becket were not satisfied, for the King had also vowed to undergo a similar public penance in England at some future date; in the meantime, he was to make reparation to the See of Canterbury and to those who had suffered as a result of supporting Becket. He was also to found three new religious houses, and—most galling of all, Eleanor knew—revoke the most contentious articles of his cherished Constitutions of Clarendon.

Of all this, she said nothing to Raoul, who knew it already. She was still incensed on Henry’s behalf that Becket, in death, had won the moral victory, when Henry had had right on his side—she was convinced of this—all along. Unwilling to pursue this line of thought any further, for she had gone over it relentlessly in her mind, seething with indignation, and knew there was nothing to do but accept what had happened, she changed the subject.

“My lord has new plans for our youngest son, John,” she said. “He is not after all to be dedicated to the Church, which, I might say, is something of a relief.” She smiled faintly as she called to mind the unruly, lively five-year-old, whom all Abbess Audeburge’s strictures had failed to tame. John, she had realized on her all-too-rare, conscience-appeasing visits to Fontevrault, was meant for the world, not for the spiritual life. “Instead, he is to be married to the daughter of Count Humbert of Maurienne. As the count has no son to succeed him, John will inherit his lands, and that will be of some advantage to Henry, because whoever rules Maurienne controls the Alpine passes between Italy and Germany.”

“What is the daughter like?”

“Alice? She’s a mere child. As usual, my lord is resorting to hard bargaining. I doubt we will see them betrothed for many a month.”

“And is John to stay at Fontevrault now that he is not to enter the Church?” Raoul looked at Eleanor searchingly.

“That is for Henry to decide,” she said firmly. “I am more concerned about the Young King.”

She had been worrying about her eldest son for some time now. At seventeen, the younger Henry was ambitious and thirsty for power. He was a king, but he had no real authority beyond the superficial privileges that his father allowed him, and that had made him increasingly resentful.

“Geoffrey has Brittany, and Richard is to have Aquitaine, and both already have the freedom of their domains, yet I, the eldest, am ruled by my father,” he had complained, his eyes blazing, just before Eleanor left Argentan. “My titles are meaningless! I have asked him again and again to let me govern at least one of the lands I am to inherit—England or Normandy, even Anjou or Maine—Mother, I would even settle for Maine!—but he will not relinquish any part of his power, even to his own flesh and blood. I asked him if I could rule England as regent during his absence, but he appointed the justiciar instead.”

“I will talk to him,” Eleanor told him, but of course there had been no way of approaching Henry at that time, not when he was suffering agonies of guilt over Becket’s murder.

“It’s not just that,” the Young King had added. “He keeps me short of money. Even William Marshal thinks so. I have had to exist on what I can purloin from the Treasury or what profit I earn from tournaments. My father forgets I have a reputation for open-handedness to maintain. But what does he do? He bans tournaments in England, because he says that too many young knights have been killed. And he reserves the right to choose the members of my household. Mother, am I a king, or am I not? I cannot see why Father made me one, just to treat me like a child.” The boy was in anguish.

“It is hard for a father to accept that his children are grown up,” Eleanor soothed, “much less that they will one day hold what is his. Your father takes great pride in his domains. No English king before him had such an empire. I counsel you, my son, be patient, and act prudently in all things. You are young yet, and must prove yourself worthy.”

After the Young King had gone away, sullen and unmollified, Eleanor reflected that her wise words had not been what he had wanted to hear. Yet she knew him well, and she knew too why Henry was keeping him on a tight rein. Young Henry was a restless youth, inconstant as wax. He was a spendthrift, and had shown himself to be lacking in wisdom and energy. He had not yet learned to control the violent temper he inherited from his Angevin forebears, and probably never would. If the father couldn’t do that, there was no hope for the son. But Eleanor was confident, with a mother’s instinct, that given the privilege of adult responsibilities, Young Henry would quickly learn to live up to them. It was being treated like an incompetent child that was turning him into a wastrel. But Henry could not see that. He did not realize that he was driving a wedge between his son and himself.

“Henry is a doting parent,” she told Raoul now. “He lavishes more affection on his children than most fathers, and takes it for granted that his love is returned. He cannot see any faults in his offspring, and they know well how to deflect his wrath by bursting into tears. It never fails!”

“You are both indulgent and loving parents,” her uncle pointed out. She accepted the implied criticism, knowing it to be justified.

“Yes, I know. We have spoiled our children, and as a result, they are too headstrong for their own good. And unfortunately they have been witnesses to much discord between us, so they have learned to compete for our attention, and to play off one parent against the other shamelessly!” She threw a mock grimace at Raoul. “I have failed as a mother!”

It was a remark lightly made, but it masked an underlying anxiety. Despite the balmy night, with stars studding the clearest of skies, Eleanor felt a sudden chill. She ripped off a leaf from a creeper and began crushing it in her palm.

“You may recall a curse laid by a holy man on Duke William the Troubadour, my grandfather,” she said. “He swore that William’s descendants would never know happiness in their children. I told Henry about it once, long ago, and it quite upset him, because he could not imagine any of our brood causing us grief. Of course, they were small then, and easy to rule.”

“Does any parent ever know happiness in their children?” Raoul asked. “We nurture them, we love them as our second selves, then they go away and leave us. It is the natural course of things. Every time they are hurt, we suffer. If they forget us, we suffer. Is that happiness?”

“What on earth did you do to your children, Raoul?” Eleanor exclaimed, trying to inject some humor into the gloom. Yet there was an uncomfortable degree of truth in what he had said, and she felt depressed by it. Then she remembered something else.

“There is another ancient prophecy, Raoul, of Merlin’s. It has always puzzled me, and yet I have increasingly come to feel that it has some relevance for me and mine. It says that the ‘Eagle of the Broken Covenant’ shall rejoice in her third nesting. Is that prophecy to be fulfilled in me? Am I the eagle? And the broken alliance? Is that my marriage to Louis?”

“It is too vague to say,” Raoul opined dismissively, and began to walk toward the door that led to the abbey guest house. “I should not concern yourself with it.”

“Yes, but if it is about me, then it portends well for Richard. If you think of my living sons, then Richard is the third nesting, of whom I shall have cause to rejoice. I am almost convinced that he will be the fulfillment of the prophecy. It’s what might be meant by the ‘broken covenant’ that worries me.”

“Eleanor, you are worrying over nothing,” her uncle told her. “Let it alone. I am sure that, prophecy or no prophecy, Richard will fulfill your every hope.”

The Young King had been crowned again, with Queen Marguerite, in Winchester Cathedral. Now, Eleanor hoped, Henry would permit their son to exercise more power. He had written to say that since Marguerite had reached the age of fourteen, he had allowed the young couple to consummate their marriage and live together. That sounded promising; it was a start. But hot on the heels of that messenger came another from Young Henry himself.

He wrote indignantly that his father now insisted on keeping him under his eye at all times. He had dragged him from Normandy to the Auvergne to witness the betrothal of John to Alice of Maurienne, and when Count Humbert had asked what John’s inheritance would be, Henry promised to give him three castles. “But they are mine!” the Young King had dictated. “They were to come to me.” He made his anger clear to his father but had been ignored. Instead, Henry forced him to witness the marriage treaty that dispossessed him.

Henry was acting like a bull-headed fool, Eleanor thought. He loved his children, true, but when it came to inheritances, he was back to his game of pushing them around like pawns on a chessboard, with no thought for their feelings. All was policy, and often there seemed no rhyme or reason to it! But what of the wider implications of his heavy-handedness? Did he not realize that a house divided against itself falls?

The next she heard, King Louis had invited his daughter Marguerite and the Young King to Paris. That in itself was worrying.

“Louis has long been trying to make divisions in Henry’s empire,” she told Raoul one morning as they rode out with their hawks. “It would not surprise me if he has heard of the Young King’s dissatisfaction and is trying to exploit it to his own advantage. He fears that vast concentration of power in Henry’s hands.”

“And the French have always liked to make trouble for the English!” Raoul observed. “Maybe the King should have forbidden Young Henry to go to Paris.”

Eleanor agreed. “Maybe he does not wish to offend Louis,” she said. “After all, Marguerite is Louis’s daughter. But I think it is folly for them to go to the French court now.”

Soon it became clear that the situation was worse than she could ever have expected. In his next letter, her son informed her that before setting out for Paris, he had visited his father in Normandy and once more demanded to be given his rightful inheritance. But Henry had again been adamant in his refusal. “A deadly hatred has sprung up between us,” the young man confided. “My father has not only taken away my will, but has filched something of my lordship.” There was a palpable sense of grievance in his words—and it was entirely justified, Eleanor felt.

Her anger against her husband was mounting. How could he be so blind? It was unfair and unjust, the way he was treating their son—and it could be disastrous in the longer term. She almost hoped Louis would do something to provoke Henry into realizing that he was acting destructively and forfeiting the love of his heir.

She wondered if there was anything that she herself could do to stop it. She felt so helpless, so impotent—and so frustrated!