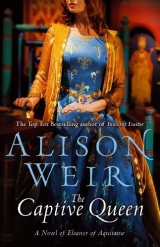

Текст книги "Captive Queen"

Автор книги: Элисон Уир

Жанры:

Историческая проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

32

32

Chinon, 1166

The court was staying at the Fort St. George, Henry’s magnificent castle of Chinon, which straddled a high spur above the River Vienne, when both the King and Queen sickened. Eleanor knew very well what was causing the familiar nausea: she was pregnant for the eleventh time, made fruitful with the seed planted that tragic night at Angers, the night when she realized that she had lost Henry in all the ways that were most important to her. Since then, matters had not improved between them, and now it seemed that there was an unbreachable distance. They still observed the courtesies, and they talked like civilized beings; he had frequented her bed on several nights, but it was like coupling with a stranger. She knew he sensed her withdrawal from him, a retreat less tactical than instinctive, born of the need to protect herself. She told herself that love was not essential in a royal marriage: she was Henry’s wife and queen; she was Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, Queen of England, Duchess of Normandy, Countess of Anjou and Maine. She was undefeatable, a match for any light-of-love to whom her lord might take a passing fancy. She dared not let the facade drop; she must think of herself as invincible.

Henry appeared not to be troubled by her studied amenity; she believed he welcomed it, for it absolved him of any need to put things right. There was no point in him trying to do that if his heart wasn’t in it. She did not want him to play a role for her: she needed his honesty, but she was damned if she would probe for it, for she feared to provoke any painful revelations. But now, here she was, pregnant with his child once more, another reason why the pretense that all was well must be maintained. And she must tell him her news.

She came upon him in their solar as he sat stitching a tear in his hunting cloak, and sat beside him on the wooden settle, struggling to suppress the rising bile in her throat. The thought of the coming months depressed her: she was weary of childbearing, had suffered it too often. She was forty-four, and she’d had enough. This, she vowed, would be the final time.

“I am to have another child, Henry,” she announced quietly. He paused in his mending.

“You are not pleased,” he said.

“If I spoke the truth, no. However, it is God’s will, and I must make the best of it. But I pray you, let this be our last child.” She looked at him as she spoke, but he would not meet her eyes. “You understand my meaning,” she persisted, her heart breaking. She had the horrible, sinking feeling that she was closing a door forever—and perhaps closing it prematurely.

Henry did not answer. The needle flew in and out.

“Henry?”

“It’s your decision,” he said.

“Do you care?” she ventured, thinking that she might as well be dead, and knowing she was about to shatter the fragile equilibrium between them.

Now he did raise his head and look at her. His eyes were guarded, his expression unreadable. There was a slight flush on his bristled cheeks; was it anger? That would be something … Surely he would not agree, uncomplaining, to what she asked. As her husband, he could insist on claiming his rights—and who knew, a miracle could happen and they might recapture the joy they had shared. She would endure ten more pregnancies for that, if he would just intimate, by one word, that he still wanted her.

“It’s your decision,” he said again, turning back to his handiwork. “You’re the one who has to bear the children. Whether I care or not is beside the point.”

“Are you accusing me of deliberately ignoring your needs?” Eleanor cried, forgetting her resolve to maintain a gentle and dignified detachment.

“I’m saying I don’t need this at this time!” Henry snarled. “I’ve got Thomas threatening to excommunicate me and proclaiming to the whole of Christendom that my Constitutions of Clarendon are unlawful. There’s trouble in Brittany, where my vassal, Count Conan, is unable to keep order, and your Aquitainian lords are up to their usual tricks. I’m not feeling well, Eleanor, in fact I’m feeling bloody awful, and you choose this moment to tell me you don’t want to sleep with me anymore!”

Relief flooded through her. He was ill. That explained much. Maybe things were not so bad after all. Then the implications of his being ill hit her like a blow.

“You are ill?” she echoed. “Why didn’t you tell me, Henry? What is wrong?”

“I feel sick to my bones,” Henry said, glad to be able to offer Eleanor an explanation—albeit a temporary one—for his coolness toward her; he could never have admitted that he no longer loved her as he had, that there was a new love in his life now. Overburdened by cares as he was, the sweet image of Rosamund remained with him constantly, his longing for her a continual ache in his loins. If that was a sickness, then yes, he was ill. But there was more to it than that.

Thomas was threatening him with anathema. Flippant as Henry could be in regard to religion, he still feared eternal damnation, and of being cast out from the communion of the Church. Where would that leave him as a ruler who held dominion over all the territories from Scotland to Aquitaine? When a man was excommunicated, all Christians were bound to shun him; he could not receive the Blessed Sacrament, or any of the consolations of his faith. He would be as a leper.

He knew, though, that it was forbidden to excommunicate a man who was sick. The Church, in her wisdom and mercy, held that the sick were weak in judgment and incapable of rational thought. It would make good sense, therefore—for so many reasons—to take to his bed and feign illness.

So he took to his bed, and had it given out that he was laid low by a mysterious malady. He even fooled his doctors, groaning and rolling his eyes in mock pain as they approached. A mystery illness indeed, they agreed, conferring privately among themselves. Had they not seen the King in such evident discomfort they would have said there was nothing wrong with him.

Eleanor was at her wits’ end. Henry had not thought fit to take her into his confidence, so she was terrified of him dying, and distraught at the doctors’ failure to cure him. When she came to sit beside him, he affected to be all but comatose, suffering her ministrations in silence and wishing she would go away. Nothing further had been said by either of them on the subject of their quarrel: the issue remained unresolved, although, a thousand times each day, Eleanor crucified herself for what she had said. She made bargains with God; she demanded that He heal Henry; and when He had done that, she beseeched Him to make things right between them. Daily, on her knees, she nagged, pleaded with, and bullied Him as if He were one of her subjects.

Henry had lain abed for two months, and Eleanor was beginning to lose all hope of his recovery, and to worry if Young Henry was ready for the heavy task of ruling the empire, when news came from Vézelay.

“Becket has excommunicated all those who formulated the Constitutions of Clarendon,” announced the Empress, who, frail as she was, had traveled from Rouen to be with her ailing son. Wearily, she climbed the stairs to the Queen’s bower to convey the latest tidings to her exhausted daughter-in-law.

Eleanor swayed. It had come, this news they had all dreaded, the fear of which—she had begun to suspect—was one of the causes of Henry’s malady.

“Sit down, Eleanor!” the Empress commanded. “You must think of the child you carry, and take comfort from the fact that Henry is not included with the rest, on account of his illness. Even Becket did not dare to go so far.”

“Thanks be to God,” Eleanor breathed fervently, collapsing onto a stool with relief. “We must tell Henry at once.”

They found him propped up on his pillows, partaking of a little pottage. When they told him the news, his face contorted and he wept in such rage that they both feared he might suffer a relapse.

“The bastard! I will have him. I will ruin him! He will not defy me again, I swear it, by the eyes of God!” And then he fairly leaped out of bed, this invalid who had been almost at death’s door, with all trace of his illness gone. His wife and his mother looked at each other in astonished incomprehension. Then, as Henry shouted for water to wash in and clean clothes to put on, realization dawned—and, for Eleanor, the bitter understanding that he had not been ill at all, but carried on this long-drawn-out charade without a word in her ear; that he had let her suffer prolonged anguish and fear, and not thought to alleviate her misery. How, she wondered bitterly, could things ever be right between them after this?

Henry was still yelling his head off, heedless of his mother’s admonishments.

“My son, you must have a care to your health!” she enjoined him.

“There’s nothing wrong with my health!” he retorted, then his furious eyes met Eleanor’s appalled ones, and he had the grace to look guilty. But the moment was fleeting.

“I will write to the Pope, and to Frederick Barbarossa,” he vowed. “I will demand that the excommunications be revoked.”

“I have no doubt His Holiness will comply,” the Empress said. “He needs your support, and the Emperor Frederick’s. I, for my part, intend to write to Becket and give him a piece of my mind for showing such base ingratitude for all the favors you have showered upon him.”

“Thank you, Mother. Someone needs to make my Lord Archbishop see sense.”

“I shall warn him,” Matilda went on determinedly, “that his only hope of regaining your favor lies in humbling himself and moderating his behavior. I shall go and write the letter now, so that he may see how angry I am. And, my son, I rejoice to see you restored to health. Your recovery is no less than miraculous.” Her tone was sardonic.

When she was gone, and the sound of her footsteps had faded down the stairwell, Henry looked again at Eleanor, who had said not a word.

“I couldn’t tell either of you,” he explained. “You had to believe I was ill, so that others would be convinced.”

“You think I can’t act as well as you?” she answered in an icy tone. “You don’t know the half of it!”

Henry raised one eyebrow questioningly, but did not rise to the bait. He could not be troubled with confrontations with Eleanor at this time; his mind was busy elsewhere.

“I will have that priest!” he seethed. “I will crush him to the ground.”

33

33

Rennes, 1166

Eleanor was present in the cathedral of Rennes when Henry formally took possession of Brittany, having deposed his ineffectual vassal, Count Conan. It was a triumphant day, coming as it did so soon after the Pope had ordered Becket to annul his sentences of excommunication and molest his king no more.

With Henry formally invested with the insignia of the newly created Duchy of Brittany, the Archbishop now sealed the betrothal of eight-year-old Geoffrey to Conan’s daughter Constance, a proud little lady of five. Try as she might, Eleanor could not take to this blond-haired madame, with her pixie face, winged eyebrows, and posturing, imperious manner. She had been spoiled and allowed her head, and Eleanor feared that Geoffrey would have his work cut out to control her in the years to come, unless she, Eleanor, took steps to discipline the little minx. And that she would do, she promised herself. Constance could have her moment today, but after that she must be taken in hand.

Eleanor gazed fondly at Geoffrey as he joined hands with his pouting betrothed. He was a dark, handsome boy, devious by nature, it was true, but clever and charming. He was to be Duke of Brittany when he married, Henry had decreed, but until then his father would hold and rule the duchy for him. It was gratifying to have the boy’s future so happily and advantageously settled, and the problem of Brittany brought to such a satisfactory conclusion.

There was but one jarring note to mar this day of celebration, and that was Eleanor’s nagging awareness that although Young Henry’s and Geoffrey’s futures were mapped out—Henry was to have England, Anjou, and Normandy—and brides had been found for both of them, Henry had as yet made no provision for her adored Richard, his middle son.

She tackled him about this as they presided at the high table over the feast that followed the ceremonies in the cathedral.

“It more than contents me to see two of our boys settled,” she began diplomatically, “but tell me, what plans have you for Richard?” Her eyes rested on the nine-year-old lad with the flame-red curls who sat gorging himself on some delicious Breton oysters and scallops farther down the table. A strong child he was, a vigorous child, who was surely destined to make his mark. What she was really determined upon was to make him heir to all her dominions; and she believed that was what Henry too had in mind for Richard. It would be entirely fitting.

“Not yet,” Henry said, his mouth full of lamb. “But, since you mention it, I have something in mind for Young Henry, and I should like your approval.”

“And what is that?” Eleanor asked.

“I want to make him your heir in Aquitaine.”

“No!” she told him, shocked. “Why Henry? What of Richard? That would leave Richard with nothing!” Her face had flushed pink with fury, and a few of the revelers were looking at her curiously.

“Calm yourself,” Henry muttered. “Do you think I would not see Richard well provided for? Does it not occur to you that it would be better to keep this empire of mine in one piece, under one ruler? There is strength in numbers, Eleanor, and by God I need all the strength I can get to keep your vassals in order. It’s one thing to confront them with the Duke of Aquitaine, quite another when that duke is also to be King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Maine, and Count of Anjou. You must see that!”

Eleanor did not. All she was aware of was the need to fight for the rights of her beloved. “Richard is but two years younger than Henry. You know he has the makings of what it takes to rule Aquitaine, he is a true child of the South, and I want him as my heir, and to see him settled as Henry and Geoffrey are settled. It would only be fair.”

Henry turned to her, his face set. “Trust me. I will see Richard settled.”

“With what?” she asked defiantly. “All your domains are spoken for. What if you died after naming Henry my heir? Richard would be left landless!”

By now a lot of the guests were watching them speculatively as they quarreled. Eleanor saw it but did not care. All that mattered was Richard’s future. But Henry, seeing that their discord was observed, resolved to put an end to it.

“It’s no use arguing, Eleanor,” he said. “My mind is made up. I but asked for your approval as a courtesy. You know I do not need it. There is no more to be said, except that after these celebrations are over, I intend to deal once more with your ever-impudent seigneurs, and then go to Poitiers, where I shall hold my Christmas court and present Young Henry to your people as your heir. I should like you to be there too, obviously, to show some solidarity.”

“Never!” she retorted furiously. “I will go to England and stay there until this child is born. I will not be witness to an act that effectively disinherits Richard. Instead, I will help Matilda to prepare for her wedding journey next year.” She had decided all this on impulse, in the heat of the moment, and was wondering, even as she said it, if she would come to regret it, for going to England would mean that she would certainly not see Henry again for months. Was it wise to leave him to his own devices at a time when relations between them were so distant? She knew she might be sentencing herself to a lengthy period of emotional turmoil—but it was too late to retract. The words were now said, and she could not unsay them. Besides, she knew she had right on her side.

Henry was frowning, but he was immovable.

“You may go where you will,” he said. “I will make the arrangements.”

34

34

Woodstock and Oxford, 1166

It was cold in the wilds of Oxfordshire, and there was a promise of snow in the leaden air. The sky was lowering, the skeletal trees bending before the icy wind. Eleanor sat huddled in her litter, her swollen body swathed in furs, aware that she should find some place of shelter soon, for it could not be long now before this babe was ready to greet the world.

Poor child, she thought: it had been conceived in sorrow and would be born in bitterness, for Henry had let her go without a protest, and she’d had no word from him since. He was angry at her defiance, of that there could be no doubt, but she still maintained adamantly that she had a just grievance: the thought of Young Henry having Richard’s inheritance was an open wound that would not heal.

She was weary of the ceaseless jostling with Henry for autonomy in her own lands, enraged with him for slighting her adored boy, and tortured by the crumbling of their marriage. It was a relief to be away from him, and yet … and yet, for all that, she missed him, wanted him, needed him … The pain was relentless. She tortured herself with speculation about the possibility that she had been supplanted by another woman. There was no proof, nothing at all, but what else could have caused such a change in his manner toward her? Had he simply ceased to care for her?

She rested her head back on the pillows. It was no good tormenting herself with these disturbing thoughts—it was not beneficial for her, in her condition. She must think of her coming child.

They had been making for Oxford, hoping to get there by dusk, before the snow fell, but their battle with the elements delayed them, and the Queen now had no choice but to order that they divert to Woodstock for the night. The royal hunting lodge was a favorite residence of Eleanor’s; she had a suite of rooms there, and was hoping the steward would have kept them in a habitable condition. She did not think she could face freezing chambers, an unaired bed, or damp sheets; what she needed right now was a roaring fire, warming broth, a feather bed, and the ministrations of her women. She was weary to her bones.

At last the litter was trundled across the drawbridge, the men-at-arms clip-clopping on either side. As the little procession drew to a standstill, Eleanor parted the leather curtains of her litter, allowed her attendants to assist her to her feet—and then gaped in astonishment. For she saw that Woodstock now boasted a new, fair tower of the finest yellow stone. It was perhaps only to be expected, for Henry had been indefatigable in improving or rebuilding the royal residences, and he had spent much time doing so not long ago. What wassurprising was what lay before it, nestling within the curtain walls. It was some kind of enclosed garden—indeed, the most curious of pleasaunces—and it certainly had not been here when she last visited. She walked heavily toward it, almost in a daze. Henry had been here for much of last winter and spring, she remembered. Had he gone to the trouble of ordering it planted for her, for some future visit? And that tower? Was that for her too?

She soon saw that the pleasaunce was in fact a labyrinth, laid out in a circular design with young yews and briars; a paved path disappearing into its depths could be glimpsed at the entrance. The maze was not large, but it looked enticing, even magical—and not a little sinister—in the light of the torches carried by her people against the deepening dusk. Had Henry gone to the trouble of having this intricate thing laid out just for her? How strange! He had had no idea that she would come here in the foreseeable future.

There was a grassy path skirting the labyrinth; one branch of it led to the tower, the other to the older hall with the King’s and Queen’s solars above, but Eleanor walked past that one. She had noticed a light in the tower, at one of the upper windows; it was flickering behind grisaille glass, such as that usually found only in great churches. Could some personage of importance be lodging here? Or, more likely, was some servant about his or her duties? That would account for the light.

Suddenly, a door opened and the steward materialized breathlessly out of the gathering darkness. His face was red, his manner flustered.

“My lady, welcome, welcome!” he cried, bowing hastily. “We had no idea you were coming. I will make all ready. I pray you, come in and get warm.” He indicated that Eleanor should go before him into the large room at the base of the solar block, but she swept on.

“In a moment, I thank you. But first, I have a mind to see that impressive new tower,” she told him.

His face blanched. “Madame, I should not advise it. It is, er, unfinished, and may not be safe.”

“Someone is up there!” Eleanor pointed, and strode in ungainly fashion toward the studded wooden door at the base of the tower.

“My lady!” the steward protested, but she ignored him.

“Open the door!” she commanded. Unhappily, he did as he was bidden, and the Queen brushed past him and began climbing the spiral stairs. She was out of breath by the time she reached the first-floor chamber and had to stop for a few moments, her hand resting on her swollen belly. Clearly, there was no one on this story, and the steward had spoken the truth: the tower was as yet unfinished. Half-completed murals adorned the lime-washed walls; the wooden floor was stacked with ladders, crocks of paint, brushes, and stained rags.

When she had rested a bit, she took the stairs to the next level, a vaulted storeroom containing several iron-bound chests, some stools, and very little else. No one here either. Determined to satisfy her curiosity, she dragged herself up to the topmost story, panting determinedly, and found herself outside a narrow wooden door. Light streamed from beneath it.

Eleanor took a deep breath and depressed the latch. The door swung open to reveal a pretty domestic scene. The room was warm, heated by the coals in a glowing brazier. An exquisitely beautiful young girl was sitting before a basin of chased silver, humming as she washed herself with a fine holland cloth by the dancing light of many wax candles. She wore only a white chemise, draped around her waist, exposing her upper body. In the instant before the startled nymph gasped and covered herself, Eleanor’s shrewd eyes took in the small, pink-tipped breasts, the long, straw-colored tresses, the firm, slender arms, and the damp, rose-petal skin.

“Who are you?” she asked, aghast, already dreading the answer.

“I am Rosamund de Clifford, madame,” the girl said, her expression guarded. She had no idea who this intruder was; the woman was bundled up in a thick cloak, and the white wimple beneath it, although fine, was of a type worn by many middle-and upper-class matrons.

“And what is your business here?” Eleanor could not help her hectoring tone. She had to know who—and what—this young female was.

“I live here by order of my Lord the King,” Rosamund answered, a touch defensively. “May I ask who it is who wishes to know?”

Eleanor could not speak. Her heart was racing in horror. Was this child—for she could be no more than that—the reason for Henry’s strange, distant behavior? Had he installed her here as his mistress? Or—her mind raced on—was this Rosamund some bastard child of his?

“I am Queen Eleanor,” she said, her voice sounding far more confident than she felt, and was gratified to see the girl gather her shift about her and drop hurriedly into an obeisance.

“My lady, forgive me,” she bleated.

Keeping her on her knees, Eleanor placed one finger under Rosaimund’s chin and tilted it upward, daring her to meet her eye, but the young chit would not look directly at her.

“I will not beat about the bush,” the Queen said. “Tell me the truth. Are you his mistress?”

Rosamund began trembling like a frightened animal.

“Are you?” Eleanor repeated sharply.

“My lady, forgive me!” burst out the girl, beginning to cry. Eleanor withdrew her hand as if it were scalded. She thought she would die, right then and there, she felt so sick to her stomach. He had betrayed her with this little whore. This beautiful little whore. Her hand flew protectively to the infant under her thudding heart.

“Do you realize that this is his child?” she cried accusingly.

Rosamund did not answer; she was sobbing helplessly now.

“Tears will avail you nothing,” Eleanor said coldly, wishing she too could indulge in the luxury of weeping, and marveling that her emotions had not betrayed her further. But it was anger that was keeping her from collapsing in grief.

“Do you know what I could do to you?” Her eyes narrowed as she moved—menacingly, she hoped—closer toward the sniveling creature kneeling before her. She was filled with hatred. She wanted this girl to suffer, as she herself was suffering. “I could have you whipped! If I had a mind to, I could call for a dagger and stab you, or have your food poisoned. Yes, Rosamund de Clifford, it would give me great pleasure to think of you, every time they bring you those choice dainties that my husband has no doubt ordered for you, wondering if your next mouthful might be your last!”

“My lady, please, spare me!” the girl cried out. “I did not ask for this.” But Eleanor was beside herself with rage.

“I suppose you are going to tell me that you went to him unwillingly, that he raped you,” she spat.

“No, no, it was not like that!”

“Then what wasit like?” She did not want to—could not bear to—hear the details, but she had to know.

“My lady will know that one does not refuse the King,” Rosamund said in a low, shaking voice. “But”—and now Eleanor could detect a faint note of defiance—“I did love him, and what I gave I gave willingly.”

Her words were like knives twisting in the older woman’s heart.

“You loved him? How touching!”

“I did—I still do. And he loves me. He told me.”

“You are a fool!” Eleanor’s voice cracked as she spat out the words. “And you won’t be the first trollop to be seduced by a man’s fair speech.”

Rosamund raised wet eyes to her, eyes that now held a challenge. “But, madame,” she said quietly, “he does love me. He stayed here with me all last autumn, winter, and spring. He built me this tower, and a labyrinth for my pleasure. And he has commanded me to stay here and await his return.”

Eleanor was speechless. Her wrath had suddenly evaporated, swept away by shock and grief, and she knew she was about to break down. She must not do so in front of this insolent girl, must not let her see how deeply those cruel barbs had wounded her, far more than her empty threats could have frightened her adversary. Like an animal with a mortal hurt, she wanted to retreat to a dark place and die.

There were voices drifting up from the stairwell; her attendants would be wondering what was going on, were no doubt coming to find her. She must not let them see her here, a betrayed wife with her younger rival.

“Never let me set eyes on you again!” she hissed at Rosamund, then turned her back on the girl, glided from the room with as much dignity as she could muster, closing the door firmly behind her, and descended the stairs.

“The sewing women are up there,” she announced to the ladies who were climbing the stairs in search of her. “I was admiring their skill.” She was surprised at her own composure. “It seems that the steward was right, that many works are being carried out here. This place is wholly unfit for habitation. Like it or not, we must make for Oxford.” She knew she had to get away from Woodstock as quickly as possible. She could not endure to share a roof with Rosamund de Clifford, or even breathe the same air. She must go somewhere she could lick her wounds in peace.

“Now?” echoed her women. “Madame, you should rest before we attempt to move on.”

“There will be an inn on the road,” Eleanor said firmly.

The King’s House at Oxford was a vast complex of buildings surrounded by a strong stone wall; it looked like a fortress, but was in fact a splendid residence adorned with wall paintings in bright hues and richly appointed suites for the King and Queen. Here, in happier days long past, Eleanor’s beloved Richard had been born, slipping eagerly into the world with the minimum of fuss. But this latest babe, unlike its older siblings, did not seem to want to be born, and small wonder it was, Eleanor thought, when the world was such a cruel place.

She had no heart for this labor. She pushed and she strained, but to little effect. It had been hours now, and the midwife was shaking her head in concern. It had been a great honor, being summoned at short notice to order the Queen’s confinement, but the good woman was fearful for her future—and her high reputation in the town—for if mother or child were lost, almost certainly the King would point the finger of blame at her.

Petronilla, tipsy as usual, for she had resorted to the wine flagon to banish her demons, was seated by the bed, holding Eleanor’s hand and looking tragic, as the other ladies bustled around with ewers of hot water and clean, bleached towels. Petronilla knew she would be devastated if her sister died in childbed; she adored Eleanor, relied on her for so many things, and knew her life would be bleak without her. No one else understood why Petronilla had to drink herself into oblivion. Other people looked askance and were censorious, but not Eleanor. Eleanor had also known the pain of losing her children. She too had suffered that cruel sundering, had learned to live with empty arms and an aching heart. Petronilla knew, as few did, how Eleanor had kept on writing to those French daughters of hers, hoping to reseal a bond that had long ago been severed. She knew too that there had been no reply, apart from on one occasion, when hope had sprung briefly in her sister’s breast; but evidently, the young Countess Marie had not thought it worth establishing a correspondence—and Petronilla supposed that one could hardly blame her.

Yes, Eleanor too had her crosses to bear—and probably more than she would admit to. Something odd had happened at Woodstock, Petronilla was sure of it. Before that, Eleanor seemed strong and resolute, a fighter ready to take on all challengers. Now she appeared to have lost the will to live. It was incomprehensible, the change in her—and terrifying. Gulping back another sob, Petronilla reached again for her goblet.