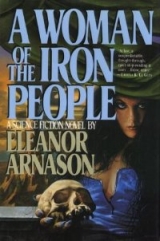

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

I had brief, horrible fantasies about allergic reactions, toxic reactions, shock, and death.

But the wound ought to be covered. I didn’t think any harm could come from a bandage.

I got out the can. “This is going to sting just a little.” I hit the button.

“Aiya!” Nia said.

The wound vanished. In its place was a small dark patch of plastic. The patch was lumpy, and clumps of hair stuck out of it, coated with plastic. Idiot! I told myself. I should have shaved the area around the wound. Well, I hadn’t and the best thing to do now was leave the wound alone. I rocked back on my heels. “Anything else?”

“No.” She took her hand out of the pot, then grimaced. “This still hurts.”

“I’ll get more water.”

I went to the stream and filled the pot again and brought it back. Nia put her hand in. Her eyes were almost shut. I had the impression she was exhausted. I tucked the cloak around her.

“Thank you.” Her voice was drowsy. She closed her eyes.

I put more wood on the fire, then got the poncho out of my pack. It was light and waterproof with a removable thermal lining. I did not remove the lining. Instead I wrapped the poncho around me, lay down, and went to sleep.

I woke later, feeling cold. The fire was almost out. I got up and laid branches on the coals. Flames appeared. How silent the canyon was! I could hear water, but nothing else. Above me stars shone. I recognized the Big Dipper. It looked the way I remembered it—maybe a little brighter. That would be the air in the canyon. It was dry and extremely clear.

I went over to Nia. Her hand was still in the pot. On her face was an expression of pain. But she was sleeping, breathing slowly and evenly.

I checked her leg. It had stopped swelling. The bandage wasn’t tight. She groaned when I touched her, but she didn’t wake. I went to my pack and got out the radio.

This time I got Antonio Nybo. Another North American. There were a lot of them on the sociology team, maybe because there were so many different societies in North America. Tony was from somewhere in the Confederation of Spanish States. I couldn’t—at the moment—remember exactly where. Not Florida. Texas maybe. Or Chicago. Most of his work had been done in southern California, studying the Hispanic farmers who were moving back into the California desert and interacting—not always easily—with the aborigines.

“Lixia! How are you?” His voice was light and pleasant with a slight accent.

“I had an interesting day…” I told him about it, then said, “Now for the problem. I don’t think the leg is broken, but I’m not sure. Is there any way to tell without doing a scan?”

“I’ll ask the medical team. Is it okay to call you back?”

“Yes.”

He signed off. I got up and stretched, then touched my toes five times. My stomach gurgled and I remembered that I hadn’t eaten dinner. I got a piece of bread. It was stale. I enjoyed it, anyway.

The radio rang. I turned it on.

“First of all they say they need more information.” I could hear amusement in Antonio’s voice. “They also say there ought to be more hemorrhaging with a fracture—than with a sprain, I mean. And hemorrhaging produces bruises—usually. Or did they say often? Anyway, if her foot turns black and blue in the next three days, she may have a fracture. But a bad sprain could produce bruising, too.”

“What are you telling me?”

“The only way to be certain is to do a scan. The medical people suggest that they come down with the necessary equipment.”

“Oh.”

“They think,” Tony said gently, “they ought to. And they would love—absolutely love—to get hold of a native. It is interesting what one finds out when one asks an apparently simple question. The aliens are not alien enough.”

“What?”

“I don’t mean at the cellular level. There—we have to assume—they are like the rest of the life on the planet. The biologists say there is no question that the organisms they have examined are alien and belong to a different evolutionary line. That is why they can say—so confidently—that we can’t catch the local diseases. Nor can we spread our own diseases to anything on the planet.” Antonio paused. “You might be interested in knowing that Eddie asked the medical team to double-check this fact.”

“Why?”

“A native died shortly after you arrived at your village.”

“I told Eddie what the woman died of. Old age, poison, or magic. There was nothing unnatural about her death.”

Antonio laughed. “Eddie was worried about the bugs in your gut. The ones that were designed to metabolize the local food. The biology team said absolutely not. The bugs can’t live outside a human. The biology team became offended and spoke about people moving outside their areas of expertise, especially people in the social sciences—which, as everyone knows, are not realsciences like biology and chemistry.”

“Ouch.”

“The problem is not at the cellular level. It’s the fact that the natives look like us. They shouldn’t, according to all the best theories. We ought to be dealing with intelligent lobsters or talking trees.

“According to the biology team, the natives are an example of parallel evolution—like the marsupial saber-toothed tiger of South America. But no one is really comfortable with this explanation. We need more information. The medical team wants some tissue samples, and they want to know what goes on the intermediate levels—between the entire organism, which looks like us, and the biochemistry, which is almost certainly alien. What are the organs like? The muscles and the skeleton? The endocrine system? The chemistry of the brain? They want—in sum—to get into a native and take a really good look around. I’m going to refer this to the committee for day-to-day administration.”

“Okay.”

“In the meantime, the medical people say to treat the injury like a fracture.”

“Okay.” I turned the radio off.

“Li-sa?”

It was Nia. I glanced at her. She was up on one elbow, staring at me. Her eyes reflected the firelight. They shone like gold.

“Yes.”

“Is there a demon in the box?”

I tapped the radio. “This?”

Nia made the gesture of affirmation.

“No.”

“Then how can it speak?”

“A good question.” I thought for a while. “It’s a way for people to talk when they’re far away from one another. My friend has a box like this. When he speaks into it, his voice comes out here.” I touched the radio again. “I can answer by talking into my box.”

Nia frowned. “Among the Copper People—the people of Nahusai—there are songs of calling. When Nahusai wanted something, rain or sunshine or a ghost, she would draw a design that represented the thing she wanted. Then she sang to the design. The thing she wanted would hear her song and come. This is what she told me, anyway.”

I made the gesture of disagreement. “This isn’t a ceremony. It’s a tool, like your hammer.”

“Hakht would not believe that.”

“What does she know?”

Nia barked. “That is true. Well, then, the box is a tool—though it’s a kind of tool I’ve never seen before. I’ve never even heard of a tool like that.” She paused. “It sounds useful. I am going back to sleep.”

I woke in the morning before Nia did. The sky was clear and there was sunlight on the rim of the canyon. I went in among the rocks and relieved myself, then went to the stream and washed. On the way back I passed the dead man. He lay on his back, his arms stretched above his head. He was large—not tall, but wide and muscular with shaggy fur. His kilt was brown with orange embroidery, and his belt had a copper buckle.

His mouth was open. I could see his teeth, which were yellow, and his tongue, which was thick and dark. His eyes—open also—had orange irises.

I was going to have to bury him, I realized. The bugs were gathering already. Damn it. I had no shovel. I glanced at Nia. Still asleep. I bent and grabbed a rock and laid it next to the body. It—he—stank of urine. Poor sucker. What a way to go. Was there a good way? I went to get more stones.

Bugs hummed around me. Clouds drifted across the narrow sky. They were small and round like balls of cotton. My back started hurting. I scraped one hand on the rough edge of a rock. The injury wasn’t serious. It didn’t even bleed, but it stung.

Finally the man was out of sight, hidden by pieces of rock. Enough. I didn’t have to make him a tumulus. I straightened. By this time the clouds were gone. Sunlight slanted into the canyon. Nia was sitting up.

“Good,” she said. “His ghost should have a home. Otherwise, the wind will take him and blow him across the sky. That is no fate for anyone.”

“Is there any ceremony that ought to be performed?”

“No. If a shamaness were here, she would sing. That would avert bad luck. I do not know the right words nor what to burn in the fire.” She frowned and scratched her nose. “I ought to do something. I will give him a knife. A parting gift.”

“All right,” I said.

We ate breakfast. I bandaged Nia’s hand. We didn’t talk much. Nia looked tired, and I found myself thinking about the dead man under his heap of stones.

Midway through the morning my radio rang.

“Your box,” Nia said. “It wants to talk with you.”

I turned the radio on. “Yes?”

“Lixia? This is Antonio. I talked to the day-to-day committee.”

“Uh-huh?”

“They voted ‘no.’ And then they decided this was not an administrative problem. It was a question of policy. I wasn’t at the meeting, but there must have been someone on the committee who got upset with the vote and raised the question of policy in order to get another chance.”

I nodded agreement to the radio.

“So the question was referred to the all-ship committee. We had the meeting. An emergency session, but a good turnout nonetheless.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“Eddie—of course—is against any kind of intervention. You know his arguments. I won’t repeat them. Ivanova went along.”

“She did?”

“According to her, we decided not to reveal ourselves to the people here until we knew more about them. There are good reasons for our decision: our own security and the fear of endangering the native culture through ignorance. How do we know what kinds of information they can handle?

“Now—according to Ivanova—we are asked to abandon a carefully thought out, democratically decided, historically important course of action. Because of a hairline fracture. A possible hairline fracture.

“She would have a different opinion if one of our people was in danger. But the person with the injury is a native, and the injury is not in the least bit dangerous.”

“Huh,” I said.

“As for our friends from the Chinese Republic,” Antonio paused for effect.

“Yes?”

“They said this never would have happened if the members of the survey team had been properly trained.”

“What does that mean?”

“You ought to have gotten a course in socialist medicine. Acupuncture, herbal lore, and Marxist ideology. As far as I can figure out, you are supposed to stick your companion full of needles and read selected passages from the Communist Manifestoto her.”

“Who came up with this wonderful line of reasoning?”

“Who do you think? It’s a perfectly preserved ancient Chinese argument. It came from a perfectly preserved ancient Chinese. Mr. Fang.”

The Chinese had said it was hard to go to the stars without children and crazy to go without people of age and experience. The rest of us had remained firm re children. There were none on the ship. But we had taken a number of people over sixty and a few over seventy. Mr. Fang was close to eighty, a thin man with long white hair and thick gray eyebrows. He was from Zhendu in Sichuan, a master wicker worker and a master gardener, in charge of the main room in the ship’s garden. Bamboo grew there, a dozen or more varieties. Along the walls were trellises covered with climbing palms. These were the raw materials for furniture. Most of the furniture on the ship was bamboo or rattan. Mr. Fang repaired it when it broke and made new furniture when needed.

I liked him. I had spent hours in his shop watching him work. From time to time we talked about philosophy. He especially liked the ancient Daoists and Karl Marx.

“They respected—at least in theory—the wisdom of the people. That is what matters, Lixia. A philosopher who fears or despises the people will come up with monstrous ideas.”

“How did the vote come out?” I asked Tony.

“What do you expect? We talked for hours and ended up where we started. For the time being we will stick to our original decision. We won’t go down to the planet—except maybe to help our own people. You are on your own. The medical team is not happy.”

“Ah, well.” I scratched my head. “What do I do now?”

“Continue to treat the injury as if it were a fracture. Keep it in a splint. Keep your friend off that foot. Time heals all wounds.”

“Wonderful. If that’s all the advice you have to offer, I’m going to sign off.”

“Good luck.”

I turned the radio off, then glanced at Nia.

“What did your box say?”

“You’re supposed to stay put till the ankle heals.”

She grimaced. “How can I do that? We are almost out of food, and there’s nothing to eat here. We have to get to a village.”

“Is there one nearby?”

“Yes. A day from here. Less than a day. The Copper People of the Plain live there.” Nia clenched one hand into a fist. “What bad luck!” She hit her thigh, then winced. “I could walk a short distance if I had a stick to lean on. But I will not be able to walk to the village. And there is climbing. The path goes up in the place where the water falls.” She frowned. “You go, Li-sa. Tell the people of the village what has happened. Ask their shamaness to come and bring medicine. I will give her a fine gift. Tell her I am a smith. A good one, from the Iron People. I can make a knife that will cut anything except stone.” She thought a moment. “It won’t cut iron, either. But anything else.”

“Okay.”

“What?” she asked.

“I’ll go.”

“What is that word? Ok …?”

“Okay. It means ‘yes’ or ‘I agree.’ ”

“Okay,” Nia said. “Go now. If you walk quickly, you’ll be at the village before dark. Come back tomorrow. I’ll be all right till then.”

I got my pack and left. On the other side of the river I stopped to dry my feet. I couldn’t see Nia, but I saw smoke rising from our fire, and I saw the grave of the crazy man. I thought I saw it. Maybe it was some other heap of stones.

I put on my socks and boots. Then I turned and walked away.

A curious thing about the canyon. From a distance the walls looked bare, and the canyon floor was stone gray. But close up I saw flowers and brightly colored bugs. The six-legged animals had vanished. Now I saw creatures that looked like birds or maybe tiny dinosaurs. They stood on their hind legs, and they were covered with feathers. But they had arms instead of wings. I saw one catch a bug. It grabbed the bug with little clawed hands and opened its mouth. I saw rows of teeth. A moment later—crunch! The bug was gone.

The hunter tilted its head and looked at me. I returned the gaze. The creature had blue feathers except on its belly and throat. The belly was white. The throat was sulfur-yellow.

The creature hissed at me.

“Oh, yeah?” I said.

The creature ran away.

At noon I stopped and ate. Above me birds soared on the wind. A fish jumped in the river. I rested for a while, then went on. The river got more turbulent. The trail began to go up and down, twisting around great rough lumps of a grayish-black stone. Ahead of me I saw the end of the canyon: a wall of stone, badly broken, full of crevices. Water ran down through the crevices, appearing and disappearing. At the top the water was in sunlight. It glittered like silver. Farther down, in shadow, it was gray. At the bottom of the cliff was a pool, half-hidden by mist.

Even at a distance I could hear the sound of the water. It was a continuous low roar.

I kept going. The trail went along one side of the pool. The canyon wall was next to me. Designs had been cut in the rock: spirals and triangles and the figures of animals.

Aha! I thought. A sacred place. But sacred to what? The spirals might represent the sun. Back on Earth the triangle was often a symbol of fertility or female sexuality. The animals were local species, or so I assumed. A quadruped with horns. A biped with a neck like an ostrich and long narrow arms. Were they worshipped or hunted? Or both?

The wind blew spray toward me from the waterfall. The trail became slippery. I decided to concentrate on my footing.

The trail went around a tall rock covered with pictographs. On the other side was a man. No question about his gender. He was naked, and his male member was large enough to be conspicuous. He was dancing, hopping from one foot to the other. He carried a pole. On top was a pair of metal horns, green with corrosion. Copper, almost certainly. The man spun and waved the pole, then spun back so he was facing me. He wore one thing, I realized now. A string of large, round, bright blue beads. They reminded me of faience beads from Egypt.

He stopped dancing and stared at me. I stood without moving, looking back. He was my size, maybe a little wider. His fur was dark brown and shaggy. His eyes were large and pale yellow.

He said something I didn’t understand.

“I do not know that language,” I said.

“You speak the language of gifts,” he said. “You must be a stranger. I thought you were a demon, but a demon would have understood me.” He frowned. “I suppose you might be a demon from far away. A demon from far away might not know the language of my people. Are you one?”

“A demon? No. I’m a person. My name is Lixia. Who are you?”

He looked surprised. “The Voice of the Waterfall. Haven’t you heard of me?”

“No.”

“You must be from very far away.”

“Yes.”

“I speak for the spirit of the waterfall. It is powerful and knows almost everything.” The man sang:

“It knows

what the fish say

in the water.

“It knows

what the birds say

on the wind.

“It knows

what the demons say

deep underground—

“The movers,

the shakers,

the ones who send up fire—

“It knows

what they say

to one another.

“People ask me questions. I tell them what I hear in the sound of the water.” He hopped on one foot and turned, still hopping. Then he staggered and came down on both feet. “What do you want? Why are you here?”

“I’ve been traveling with one of your people. She is hurt, and I’m looking for help.”

The man frowned. He waved the pole and shouted:

“O waterfall,

tell me,

tell me what to make of this.”

He tilted his head and listened. I listened too, but heard nothing except the roar of the water.

“The waterfall says you are probably telling the truth. In any case, the waterfall says, it is bad luck to give trouble to travelers or people who ask for help. Therefore I will help you. Come along.” He turned and walked up the trail. I hesitated a moment, then followed. It was never a good idea to argue with an oracle, especially one from a society you didn’t understand. Soon we were a good distance above the pool. I looked down and saw churning water. Part of a rainbow shone faintly in the mist.

The trail entered a crevice. We walked between black walls of stone. Water trickled down. There were patches of shaggy orange vegetation on the rock. A creature walked between the patches. It was level with my shoulder and moving slowly, Earth-sky-blue with at least a dozen legs. Two antennae stuck out in front of it, waving gently. Two more antennae stuck out behind. They also waved gently. I couldn’t see a mouth or eyes.

I assumed that the animal was traveling forward, but I had no way of telling. I thought of picking it up. Maybe there were organs visible on the underside. But I had never liked animals with more than eight legs.

My guide was moving quickly. I followed him, slipping now and then on the wet stone.

We were coming to the end of the passage. The walls were only a couple of meters tall. On top of them plants grew. I saw leaves and stalks and flowers.

The height of the walls decreased further. I could see over them and over the vegetation. We were coming out onto a plain.

Off to one side was a bluff—a low one, dotted with trees. In every other direction the land was flat and covered by a plant with long, narrow, flexible leaves. The plant was about a meter tall. Its color varied: green and blue-green, yellow-green and a silvery blue-green-gray. I couldn’t tell what the differences in color meant. Was there more than one kind of plant growing on the plain? Or did the color represent variations within a species?

“There.” The man pointed at the bluff. “The river is there. The trail goes along it. Follow the trail. At nightfall you will come to a village. Ask for the shamaness and say you have a message from the Voice of the Waterfall. Tell her the waterfall says give this person what she asks for. Say there is no harm in this. I know. The waterfall has told me.

“Do not disbelieve me,

O you people.

I know what the river knows.

“I know the secrets

discovered

by the rain.”

He waved his pole and danced sideways, then spun and pointed down the trail. “Go!”

I went. When I got to the top of the bluff, I looked back. I could see the trail, winding through the pseudo-grass, but I couldn’t see the man. He must have returned to the canyon and the waterfall.

I scrambled down the slope toward the river, which was wide and shallow here, shaded by trees with dark blue leaves.

In the middle of the river was a gravel bar. Half a dozen creatures rested there: large hairless quadrupeds with tails. One lifted its head and stared at me, then croaked a warning. They all got up and lumbered into the water.

Lizards, maybe? The name seemed appropriate, and it gave me a label. Though I would have to remember that these creatures were not real lizards.

I reached the village at sunset. It stood on top of the river bluff, and all I could see at first was a wall made of logs. Smoke rose from behind the wall. Cooking fires. A lot of them. On the wall were standards like the one the oracle had carried: long poles that ended in metal horns. The horns gleamed red in the sunlight. Polished copper, I told myself.

I climbed the trail up to the gate. A woman was standing there, watching the sun as it went down. She was dark like the two men in the canyon and dressed in a bright blue tunic.

“Make me welcome,” I said.

The woman turned.

“Who are you?”

“A traveler. The Voice of the Waterfall told me to come here.”

“Did he? Come in. You got here just in time.”

We entered. She closed the gate and put a bar across it. “There!” She brushed off her hands. “Come with me. I’ll take you to the shamaness.”

I followed her along a narrow street that wound back and forth between houses. The houses were octagonal, built of logs. The chinks between the logs had been filled with a fuzzy yellow plant that seemed to be alive and growing. The roofs were slanted, going up from the edges to the center, where there was a smoke hole. I couldn’t see the holes, but the smoke was obvious, rising from almost every house. The roofs were covered with dirt—an excellent form of insulation—and plants grew in the dirt. They were small and dark. I reached up and picked a leaf. It was round and thick and waxy. I squeezed. Water squirted out. A succulent or something very like. Chances were it would not burn, which was all to the good. Sparks would float out of the smoke hole. If they landed on a dry plant, these people would have a prairie fire going over their heads. What was the plant for? Was it edible? Was it decoration?

The woman stopped in front of an especially large house. “O shamaness, come out!”

The door opened. A woman came out, short and fat, wearing a long robe covered with stains. The robe was off-white, and the stains were easy to see. A poor choice for an obvious slob. She had on at least a dozen necklaces. Some were ordinary strings of beads. Others were elaborate with chains and bells and pendant animals. Everything was copper, and everything was tangled up. I didn’t think there was any way she could have taken off just one necklace.

“This very strange person has come, o holy one. She says she has a message from the Voice of the Waterfall.”

The shamaness peered at me. “Where is your fur? Have you been sick?”

“No. I come from far away. My people don’t have fur.”

“Aiya! This is strange indeed. What is your message?”

“The Voice of the Waterfall says he wants you to help me.”

“No.”

“What?”

“That man could not have said that. He has no wants. He has no opinions. He is the Voice of the Waterfall. When he speaks, it is the waterfall speaking. Therefore, what you said was wrong. It is not that man who wants me to help you. It is the waterfall who wants me to help you.”

The other woman made the gesture of agreement.

“What do you need?” the shamaness asked.

“I have a friend who has been injured. She is a day from here—to the east, in the canyon. Will you go for her?”

The shamaness frowned and scratched her chin. Then she made the gesture of assent. “Tomorrow.” She turned and went back in the house. The door closed.

“Aiya!” said the other woman. “This is something she never does. She never goes to people. They must go to her. But everyone listens to the Voice of the Waterfall. And that man used to be her son. She used to be fond of him. Come with me.”

I followed her to another house. Inside was a single large room. Large pillars held up the roof. They had been carved and painted red, white, black, and brown. The patterns were intricate, made up of curving lines. They seemed to represent animals. Here and there I saw faces and hands with claws. The faces had copper eyes and copper tongues that curled right off the pillar.

In the center of the house was a fire burning in a pit. Three people sat close to it. They were children, about half-grown. They played a game. One threw a bunch of sticks. Another bent and looked at the pattern. “Aiya! What luck you are having!”

The third one looked at us. “What is this?”

“A person. Be courteous. Bring us food to eat.”

We sat down. The woman said, “I am Eshtanabai, the go-between. It’s fortunate that I was at the gate instead of some ordinary woman.”

“You are a what?”

The children brought bowls of mush and a jug full of liquid. The liquid was sour. The mush was close to tasteless. We ate and drank. Eshtanabai explained.

“People get angry with one another. They do not talk. They sit in their houses and sulk. I go to each person. I listen to what they say. I say, This argument is no good. Is there no way to end it? What do you want? What resolution will satisfy you?’ Then I go back and forth, back and forth until everyone agrees on what ought to be done. It’s hard work. I get headaches a lot.”

“I can imagine.”

“Someone must do it. The shamaness is too holy. The Voice of the Waterfall doesn’t always make sense. And how could a man—even that man—ever settle a quarrel?”

I had no answer for that question. We finished eating, and I lay down, using my pack as a pillow. One of the children put more wood on the fire. Another child began to play a flute. The tune was soft and melancholy. I closed my eyes and listened. After a while I went to sleep.

I woke in the middle of the night with a terrible crick in my neck. The fire was almost out. Around me in the dark house I heard the sound of breathing. My companions were asleep. I sat up and rubbed my neck, then lay down. This time I didn’t use my pack as a pillow. When I woke again it was morning.

Sunlight shone through the open door. Eshtanabai was sitting by the fire. The children were gone.

“The shamaness has left the village,” she told me. “People have gone with her. They will bring your friend back.”

“Good. When?”

“Tomorrow or the next day.”

I ate breakfast—more mush—then went outside. The sky was cloudless, and the air was warm. It smelled of midden heaps. I decided to take another look at the plain. I found the village gate and went through it.

A trail led around the village. I followed it. The plain stretched south and east, almost perfectly flat. There were animals in the distance: black dots that moved from time to time. I shaded my eyes, but I couldn’t make them out.

On the north side of the village were gardens that looked exactly like the gardens in the village of Nahusai. I stopped by one.

A woman looked up. “You are the stranger.”

“Yes.”

“You certainly are strange.”

I pointed at the animals on the plain. “What are those?”

Her eyes widened. “You don’t know?”

I made the gesture that meant “no.”

“How can anyone be that ignorant?”

I said nothing. After a moment she said, “They are bowhorns. Most of the herd is in the north. In the fall the men will bring them back. The whole plain will be black then.”

“Where are the men now?”

She frowned. “Don’t you know anything? They are with the herd. Where else would they be?”

“Thank you.” I wandered on.

The next day was overcast. I went down to the river, taking my pack with me. I settled at the foot of a tree and got out my radio.

Eddie was back. “How’s your friend?” he asked.

“I don’t know. I went to get help, and the help has gone to get Nia. I’ll find out how she is sometime today.”

“Where are you?”

I described the location of the village and told him about my meeting with the Voice of the Waterfall.

“Now that sounds fascinating.” He was silent for a minute or two. Then he said, “I don’t know much about oracles. They were big in Greece, weren’t they?”

“Yes.”

“Maybe I ought to do some reading. What is the village like?”

I described the village. “As far as I can tell all the adults are women. The men are up north, taking care of a herd of animals. They’re migratory. The women stay put. How is the ship?”

“Pretty much the same. We got a message from Earth.”

“Oh, yeah?” I felt the usual excitement. “Anything interesting?”

“There’s a new space colony, and the Ukrainians are beginning to settle the wilderness around what used to be Kiev. And someone has come up with a practical faster-than-light radio. They have sent us the plans.”

I rocked back on my heels. We wouldn’t be isolated any longer. We wouldn’t have to wait forty years for the answer to a question.

“How long will it take to build the thing?”

Eddie laughed. “We can build the receiver. The engineers are almost sure of that. But in order to send messages, we have to be able to generate a very strange new particle, and the machine that does that is big.”