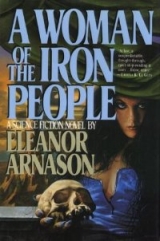

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

I knelt and touched the edge of the flower.

Damn! I waved my hand in the air. The flower curled into a ball. I looked at my finger. It felt as if a bee had gotten it.

A shadow fell over me. I glanced up and saw Nia.

“That is a stinging flower.”

“I never would have known.”

“Come into camp. There is a lotion that will make you feel better. My cousin is certain to have it.”

I stood, my hand throbbing. We walked toward the village.

Nia said, “They eat bugs and other animals. Very small lizards. Sometimes an aipit.”

“A what?”

“It is an animal with four feet, covered with fur. The body is as long as the first joint of my thumb. The poison in the plant will kill something that small. But the plant does no real harm to people. It can’t get through a good coat of fur, the kind we have. People get stung if they touch the plant the way you did—or if they are foolish enough to walk on the plain with bare feet.” She paused for a moment. “A bowhorn can walk through a cluster of the plants and feel nothing, unless it is a fawn and tries to nibble. They do that once.”

We reached the village. Nia stopped in front of a big tent. A woman sat at the entrance, large and handsome, dressed in a navy tunic. Her necklace was silver and amber. Her bracelets were gold.

“This person touched a stinging flower,” Nia said.

The woman spoke in the language of the village. A child came out carrying a pot.

“Sit down,” the woman said. “My name is Ti-antai. Nia said your people are like children, always touching and turning things over. You see what happens? Hold out your hand.”

I followed orders. She looked at my finger, which was swollen by this time and bright red. “Aiya! How peculiar!”

“What?” I asked, feeling a little nervous.

“The color of your skin.” She dug into the pot, bringing out a glob of something yellow, grabbed my hand firmly, and smeared the stuff on my finger. The pain diminished at once.

“What is the flower?” I asked. “A plant or an animal?”

“That’s hard to say. When it is full-grown, it has roots like a plant. But it hunts like an animal and it has a mouth—the dark hole in the center. Did you see it?”

“Yes, but I didn’t realize what it was.”

“You weren’t looking carefully,” the woman said. “You must always look carefully before you touch.”

I made the gesture of courteous acknowledgment for good advice.

Nia said, “The flowers have young that move around.”

I thought for a moment. “How do the flowers reproduce?”

Ti-antai looked at Nia. “You are right about these people. They poke into things they know nothing about and they ask a lot of questions.” She looked at me. “The flowers shrivel up at the time of the first frost. There is nothing left except a black pod. That stays the way it is all winter. In the spring it breaks open and the young come out. They are green and like worms with feet. They crawl away into the vegetation. I don’t know what they do under the leaves. But in time they root themselves. They grow. They become flowers. That’s all I know—except this. The lotion that cures the sting comes from the bodies of the young. I gather them in the spring and tie them onto a drying rack. They move for a day or two or three. Then they dry up. When they are entirely dry, I grind them up.

“Other things go into the lotion, but it is the bodies of the young that are important.”

Weird, I thought. And I was the wrong person to be listening. Marina in Sight of Olympus ought to be here.

“Now, go away,” the woman said. “You make me uneasy. Nia has always been friends with the strangest kinds of people.”

I stood and made the gesture of gratitude.

Nia said, “I will go to the boats with you. I have a message from Angai.”

We left the village, following the trail down the river bluff.

Nia said, “Angai has come to a decision.”

“What is it?”

“She will tell us this afternoon. Come up to the village just before sunset. All of you. The women and the men.” She moved her shoulders and rubbed the back of her neck. “Aiya! It was hard! All day we talked and argued. Angai and I and the oracle. The old women. The rest of the village. I got a headache.

“At night there was a feast. Angai sent the oracle away. He had to stay in a tent that had been abandoned by one of the old men. A man who went suddenly crazy and rode off onto the plain. I was allowed to stay.

“We always hold a feast after a big argument. It reminds us that we are one people. But the arguing didn’t end. Anhar told a story.”

“Who?”

“She is the best storyteller in the village. Most people like her. I don’t. She was one of the people who spoke against me the last time I was here. She had many reasons why I could not stay among the Iron People.”

We were halfway down the cliff, moving through shadowy forest. My finger had stopped hurting.

“The story isn’t one of ours. It came from the Amber People. It tells about the Trickster.”

“Do you remember it?” I asked.

Nia made the gesture that meant “yes.” “He came to a village, disguised as an old woman. The villagers thought he was the Dark One. He played many malicious tricks. Do you want to hear about them? I think I can remember most.”

“Not now. Later, when I have one of the little boxes that can remember what is said to it.”

“Aiya!” said Nia.

I asked, “What happened next?”

“In the story? The villagers realized he could not be the Dark One. He was too nasty. Even she sets a limit on her behavior.

“They tricked him into climbing into a pot of water. They put on the lid and boiled him until he was dead. The story ends with a song. It goes like this.” Nia sang:

“Hu! My flesh

was fed to lizards!

“Hu! My bones

were made into flutes!

“Hu! My music

is loud and nasty!

“Hu! My music

sounds like this!”

“The Trickster died?” I asked.

“Only for a while. He always comes back. Angai was furious.”

“Why?” We had reached the riverbank. My boat was in front of us. It smelled of coffee and bacon.

Nia said, “Anhar was saying that you are troublemakers like the Trickster, imposing on the village. But the argument was over. The decision was made. It was time to be pleasant to one another. Anhar could not stop. There are people like that. They pick at the edges of a quarrel like a child picking at the edges of a healing wound.

“I don’t know what Angai has decided, but I know she does not want to make Anhar happy.” Nia waved at the boat. “That’s all I have to tell you. Come up to the village at sunset.”

“Okay,” I said.

She left. I went onboard the boat. The folding table was up. Agopian, Eddie, and Ivanova sat around it.

“Elizaveta has been talking to the camp,” Eddie said.

“Oh, yeah?” I sat down and poured myself a cup of coffee.

She nodded. “They have seen lizards in the lake. Big ones. Half a dozen so far—keeping to the shallow water close to shore.”

I paused, my hand halfway to the milk. “Oh-oh.”

“They are putting up new spotlights and making sure that everything that smells like food is burned.”

“I thought they were doing that before.”

“Only with material from the ship. Organic matter from the planet was being buried.”

The remains of Marina’s specimens.

Agopian ate a piece of bacon. “No one is going swimming.”

“Here?”

“No. At the camp.”

“What happened to your finger?” asked Eddie.

I told them about the flower.

Eddie shook his head. “We keep thinking this planet is like Earth. I think—if we stay—we’re going to be surprised over and over, not always pleasantly.”

“Maybe. I ran into Nia up on the bluff. She said we’re supposed to go into the village late this afternoon. Angai has made a decision. Don’t ask me what it is. Nia didn’t even want to guess.”

I ate breakfast, then went for a swim. Afterward I put on jeans and a red silk shirt.

We had silkworms on the ship, of course, and a garden full of mulberry trees. But the shirt had been made on Earth. There was a union label in the back of the collar. “Shanghai Textile Workers,” it said. Next to the writing was a person—I couldn’t tell the sex—riding on the back of a flying crane. Robes flew out behind the person, and he or she held a spindle. Behind the crane was a five-pointed star.

The person on the crane was almost certainly a Daoist immortal, and the five-pointed star was an emblem of the revolution. The shirt felt wonderful against my skin.

It was a bad day: still and hot. Everyone was restless. Eddie and Derek and I worked on reports. Tatiana and Agopian ran checks on equipment. Ivanova paced from boat to boat. Only Mr. Fang seemed calm. I went over to his boat after lunch. He sat on the deck. There was a chessboard in front of him. Next to the board was a pot of tea.

“If you are looking for Yunqi, she has gone for a swim, leaving herself in a really terrible position. I can see no way out for her.” He waved at the pieces on the board.

“They’re driving me crazy over there. I’m driving me crazy.”

“Master Lao tells us that heaviness is the foundation of lightness, and stillness is the lord of action.”

“What?”

“Lenin tells us that a revolutionary needs two things: patience and a sense of irony.” He looked up and smiled. “Get yourself a cup, Lixia. I will set up the board again. We will drink tea and play chess and not worry about problems which are outside our control.”

“Are you being wise?”

“Not especially.”

“Good. I’m in no mood for wisdom.”

I went and got a cup. We played chess. He beat me.

Yunqi came back, wearing a swimsuit. It was single-piece and solid blue. Her short black hair was dripping wet. Her eyes had the out-of-focus look of severe myopia.

“Why don’t you wear contacts?” I asked.

“I like the way I look in glasses.” She put them on: two plain clear lenses in plain round metal frames.

“Yunqi is like Comrade Agopian,” said Mr. Fang. “A romantic. She likes glasses with the look of the early twentieth century. That was the age of heroes. Luxemburg. Lenin. Trotsky. Mao and Zhou.”

“I thought you didn’t like politics,” I said.

She blushed. “I don’t like endless talking—especially when people get angry. But I have always enjoyed stories of the Long March and Comrade Trotsky on the armored train.”

“She likes war,” said Mr. Fang. “As an idea. Do you want to play another game of chess?”

I said, “Okay.”

I lost again. Mr. Fang said, “It’s time to go.”

The people from the other boat met us on the trail: Derek, Eddie, Ivanova, Agopian. We climbed the bluff together.

It was hot and windy on the plain. In the village awnings flapped.

Standards jingled. Campfires danced. A tiny quadruped bounded down the street in front of us. It was the size of a dik-dik, with little curved horns. Its fur was dark green. It wore a collar made of leather and brass.

“What is it?” asked Eddie.

I made the gesture of ignorance.

Derek said, “We don’t know.”

We reached the town square. Once again it was full of people—at least the edges. The center of the square was a heap of ashes.

Angai waited for us in front of her tent. She wore a robe of dark blue fabric with no embroidery. Her belt was made of links of gold, interwoven like chain mail. The buckle was huge: a gold biped, folded back on itself. The neck was twisted. The head touched the rump. The long tail curled around the entire body. The animal’s eye was a dark red stone.

Nia and the oracle stood with her.

The crowd murmured around us. Angai held up a hand. There was silence, except for the chiming of metal and the rush of the wind.

“I’ve talked to various people,” Angai said loudly. “The old women who have learned much in their lives. The old men who have traveled far and are certainly not foolish. I have talked with Nia and the Voice of the Waterfall, who know these hairless people. I have gone in my tent alone and consulted with the spirits, inhaling the smoke of dreams.

“After listening to everything and thinking, I have come to a decision.

“I bring it to you, o people of the village. You are the ones who must approve or disapprove.

“But remember, if you disapprove, you are going against me and the spirits and the elders of the village.”

She paused and gestured toward us. Derek translated.

Ivanova said, “A smart woman. It won’t be easy to vote her down.”

Angai went on. “If you want to know what the old people said, ask them. I will tell you what the spirits told me. But I want Nia and the oracle to speak for themselves.”

“Why?” asked a voice.

Angai made the gesture that demanded silence. “I asked Nia her opinion, because she traveled a long distance with two of the hairless people. She has seen the town that they have built next to the Long Lake. She has ridden on one of their boats.”

“So has Anasu!” a child cried.

“Be quiet,” said a woman.

Angai went on. “Only a fool—only a worthless woman—refuses to ask for information from those who know.

“As for the oracle, he also has traveled with these people, and he is holy. A spirit has given him advice.”

She paused. Derek translated. Nia spoke.

“Angai asked me if these people are reliable. I said yes. So far as I know. But there are many of them, and they have differences of opinion. I have heard them argue.

“I think we can trust them. I think we can believe what they say. But I do not know for certain.

“She asked if they will do harm to the Iron People. They are not crazy. They will not harm us intentionally. But they are very different. If we make them welcome, they will change the way we see the world. They have done that to me.

“That is disturbing. Maybe it is harmful. I do not know.”

Nia paused. Derek translated. She went on. “I don’t think they will vanish. They are not a mirage. They are here and solid. If we send them off, they will go to other villages. Someone on the plain will make them welcome. I do not think there is a way to drive them out of the world. Maybe if everyone got together, it could be done. But that will not happen, and I don’t know if it ought to happen. Change is not always bad. There was a time when nothing existed. Spirits appeared out of the nothing. They made the world and everything in it. Most of us think this was a change for the good.

“My advice to Angai is—make them welcome. But do it carefully. O my people! Thinkabout what you are doing!”

The oracle stepped forward. “I don’t have much to say. My spirit is old and powerful. It has given good advice to the people of my village for many generations. It told me to go with these hairless people and learn from them. What they know is important, my spirit said.

“I have done this, traveling a long distance with Lixia and Deraku. We have met many people and also several spirits. Some bad things have happened, but not because of those two.”

I thought he was being kind. I had mishandled the meeting with Inahooli, and Derek had been irresponsible about the bracelet he had found in the old volcano.

Someone asked, “What kind of bad things?”

“We had trouble with the Trickster,” the oracle said. “You know what he is like. A malevolent troublemaker! He likes to turn people against one another. He likes to make them forget all the old customs and the right way to behave.

“And we met a spirit north of here, not far from the river. It was in a cave.” He paused. “It was one of those things that are found in dark places, usually underground. They have various names. The Old Ones. The Unseen. The Hungry.

“Most of the time, they aren’t a problem. They sleep in their dark place. Sometimes they wake up and notice people. Then they are likely to cause trouble—out of hunger or a stupid anger.” He paused. “I have forgotten what I was going to say.”

“I asked you to give your opinion of the hairless people,” Angai said. “But you went off about spirits.”

He made the gesture of agreement. “I can’t tell you what to do. You aren’t my people, and you have your own spirits to give advice. But I like Lixia and Deraku, and I don’t think these people without hair are dangerous.”

He stopped. Derek translated.

Eddie said, “Wrong!”

The square was darkening. People brought out poles made of metal and stuck them in the ground. They placed torches in brackets on the poles. The torches streamed in the wind, flaring and dimming. Most were close to Angai. She and Nia and the oracle were pretty well lit. But the light kept changing in intensity. Shadows jumped and flickered. Faces, hands, eyes, and metal ornaments went in and out of darkness.

“Nia has spoken clearly,” Angai said. “And the oracle is worth listening to, even if he is not always clear.”

A voice said, “What is your opinion? You are the shamaness here. These other people are strangers.”

“I will tell you.” She waited a moment. The bells on the standards went ching-chingin the wind. A baby cried briefly.

“I think Nia is right. We ought to welcome these people, as we have always welcomed strangers, not out of fear of the Dark One, but out of the respect for the spirits and for decent behavior.

“I think Nia is right in a second way. This is a time for changes. We cannot ignore the changes. When the ground shakes and old trails go in new directions, only a fool pretends she can travel the same way as before. The wise woman says, ‘This rock is new. That slope was not here last summer.’ ”

Angai straightened up to her full height. She looked around commandingly. “Listen to me! This is my decision! We will welcome the hairless people. But we will do it carefully. Like a wise traveler, we will go one step at a time.”

She paused. Derek translated.

Eddie said, “Damn!”

Angai went on. “The hairless people can stay in the village they have built so long as they remember that this is not their country. They are visitors.” She looked at us. “Do not move your village without asking permission, and do not ask more of your relatives to come and stay with you. I don’t want our country to fill up with hairless people.

“Nia says among your people men and women cannot be separated. Therefore—it is my decision—you can live in your village according to your customs. But when you visit us or any other ordinary people, leave your men at home.”

“Shit,” said Derek.

“I will not have men in this village again. It is too disturbing. The old women become angry. The children get new ideas.”

Angai stopped. Derek translated.

“This is good,” said Ivanova. “But not as good as I had hoped.” She paused for a moment. “It’s a beginning.”

“It stinks,” said Derek. “How can I do fieldwork? I have to be able to go into the villages!”

“Talk to the men,” I said.

“They’ll try to kill me.”

Angai went on. “Nia says you are going to want to travel all over and ask questions and look at things. Is she right? Is this true?”

“Yes,” I said.

Angai frowned. “I am not certain what to do about that. I do not want to find hairless people in every part of our country, turning over rocks and poking sticks into holes. It is hard enough to have children.” She paused. “Stay close to the village until I have had a chance to think more about this.”

Derek translated.

Eddie said, “This isn’t going to work.”

“Yes, it will,” said Mr. Fang. “They have the right to set these kinds of limits. We have the discipline to keep within the limits they have set.”

“What about Nia?” asked a voice.

“I have not decided,” Angai said.

“We have,” said the voice. “Ten winters ago we told her to leave. She has not changed. She was a pervert then. She is a pervert now. Look at the people she travels with! Tell her to go with them. Tell her to live in their village—not here, among people who know how to behave.”

The crowd parted. I saw the speaker now: a stocky woman of middle age. Her fur was medium brown and oddly dull. It soaked up light like clay.

“That is Anhar,” Nia said.

“I will ask the spirits what to do about Nia,” Angai said. “Not today. They don’t like a lot of questions all at once.”

“You have always liked Nia,” Anhar said. “You have always protected her. You are trying to bring her back into the village.”

Angai said, “You never know when to be quiet, Anhar. I am tired of your opinions! You have a little mind, full of nasty ideas. It is like a cheese eaten out by cheese bugs. It is like a dead animal eaten out by worms.”

“Wow,” said Derek.

Anhar turned. The crowd let her through. She walked away from Angai out of the torch-lit square. I lost sight of her in the darkness.

“What about the man?” another woman asked. “The Voice of the Waterfall?”

The oracle answered. “I am going to the village of the hairless people. My spirit told me to learn from them. I have not had any new dreams telling me to do anything else.”

Angai said, “I am done speaking. You have heard my decision. Do you agree with me? Or is there going to be an argument?”

There was silence. I had a sense that the people around me were unhappy. But no one was willing to speak.

At last someone said, “What did the spirits tell you, Angai?”

“I dreamed I was on a trail I did not recognize. The country around me was unfamiliar. The ground under my feet was hot. Smoke rose from holes. I could not see where I was going.”

“That does not sound like a good dream, Angai.”

The shamaness frowned. “I am not finished! There was an old woman with me. She had a fat belly and drooping breasts. She carried a staff and it seemed to me that she was having trouble walking. Sometimes she walked next to me. Sometimes ahead. Sometimes in back. She never left me. She made noises from time to time: grunts and moans. Most of the time she was silent. Once she was in back of me, and I thought I heard her stumble. I stopped and looked back. She said, ‘Keep going. Don’t worry about me. As old as I am, I will keep up with you.’ I went on. That was the end of the dream.”

The woman who had asked the question said, “All right. I will go along with you, Angai. Even though I am made uneasy by these new people. And even though I think Anhar is right about Nia.”

Angai made the gesture that meant “it is over.” She turned and went into her tent.

I said, “You finish translating, Derek. I want to speak to Nia.”

He made the gesture of agreement.

I walked over to Nia and the oracle. A couple of women removed the torches from their holders, taking them away.

Nia said, “I am not certain that Angai was being clever. She ought to have been more polite to Anhar. Now she’s made an enemy of her.”

“No,” said the oracle. “She has changed nothing. They were enemies already. Now they can stop pretending. I have never had an enemy, but I know it’s hard work being polite to someone you hate. It makes a woman tired. She loses strength. She cannot do things that are important.”

“You’ve never had an enemy?” I asked.

“Most men do not. If a man gets angry, he confronts the person who has made him angry. Or else he leaves. The women are trapped in their villages. They spend winter after winter next to people they dislike. They do not speak their anger. They cannot get away. That makes enemies. I have seen it happen.”

“Do you want to stay in the village?” I asked Nia.

She made the gesture of uncertainty.

“Do you have a place to stay tonight?”

“Here. With Angai.” Nia paused. “That was Ti-antai. The woman who spoke last. The woman who cared for your hand this morning. She was a good friend of mine when we were young.”

“Aiya!” I said.

The oracle said, “I will go with you. Angai made me stay at the edge of the village last night in an old tent that was full of holes. Even with the holes and the wind blowing through, it smelled of old age and craziness.” He paused. “Not holy craziness. The other kind.”

The square was empty except for my companions. The torches were all gone. There was no noise except the wind and Derek’s voice, still translating.

“What was the dream about?” I asked. “Why did it satisfy your cousin?”

“You don’t know much, do you?” Nia said.

“No. Who was the old woman?”

“The Mother of Mothers. If she tells us to go on through a strange country, then we will.”

“It was a good dream,” said the oracle. “I have had only a few that were that easy to understand. No one can possibly argue with it.”

Derek said, “I’m done.”

“Coming,” I said.

We left the square, walking through the dark village.

Ivanova said, “This decision is not going to satisfy anyone. The research teams are going to want to be able to travel. And Eddie, of course, is horrified that we have not been ordered off the planet.”

“That’s right,” Eddie said.

“I think the problem is vulgar Marxism,” said Mr. Fang.

“Oh, yeah?” I said.

“We oversimplify the dialectical process and we become fascinated by the drama of revolution. We forget that human history is very complex and very slow. Every big change is preceded by a multitude of small changes. There are compromises. There are failures. We take a step forward and then are forced to go back a step or even two.

“Even revolutions are full of compromise and failure. Even in the midst of great transformations, we go back. After the triumph of the October Revolution came Kronstadt and the crushing of the Workers’ Opposition.”

“I don’t understand where this is leading,” Ivanova said.

“We expected this meeting to resolve everything. We expected a revolution, the simple kind that we see on the holovision.

“We are in the middle of a revolution. It has gone on for over five hundred years. I have no idea when it will end, if ever. But it is not a simple drama. It does not move forward all the time. And there are no neat divisions. No scenes and acts. At least none that we can see. Historians put in such things later.

“Today—I think—the revolution has moved into a new stage. It has certainly moved ontoa new stage. There are new actors and new problems. But there is no resolution.”

“True enough,” said Eddie. “What we have is goddamned compromise. It isn’t going to hold. Once we are down here—”

Ivanova said, “For once I agree with Eddie. We have to be able to travel. We have come so far.” She paused. “Maybe we can find another people who will set fewer limitations.”

“Not tonight,” said Mr. Fang.

We reached the river. There were lights on one of the boats. Tatiana and Yunqi sat together on the deck. They helped Mr. Fang onboard. Ivanova and Eddie followed.

The oracle said, “I want to sleep. This has been a long day.”

“You’re right about that,” I said.

We took him to the other boat and got him bedded down in the cabin.

Derek and Agopian and I went out on deck. The river air was cool and full of bugs. They swarmed around the deck lights once we turned them on. Agopian and I sat down. Derek went and got beers.

We drank, not speaking. We could hear voices from the other boat: Ivanova and Eddie, describing what had happened to Tatiana and Yunqi.

Agopian said, “I don’t know how long that conversation will go on.”

“Hours, most likely.”

“Maybe.” He set down his bottle. “There is something I have to tell you.”

I looked at him. “Your secret. Your ethical complexity.”

“Yes.”

“Can’t it wait?”

“I’m not sure I’ll be able to get you alone. This is perfect now, if I have enough time.”

Derek said, “I’m willing to listen.”

Agopian looked at me.

I nodded.

“I’m going to try to tell this as quickly as possible. I don’t know when that conversation will end, and Tatiana will come over. There is information that has been kept hidden and lies that have been told. I think it’s time this situation was rectified.”

Derek leaned forward. “What kind of information?”

“History. What’s been happening on Earth during the past one hundred years.”

“We have the messages from Earth,” I said.

“They are lies.”

“You know this for certain?” asked Derek.

“I wrote them—with help, of course. It was too big a job for any one person.”

“Why?” I asked.

Derek asked, “When?”

“You know there was trouble coming into the system.”

Derek made the gesture of agreement.

Agopian looked puzzled and went on. “There was a lot more junk than we had expected, and a lot of it was a long way out. A kind of super Oort cloud. And there were problems with the astrogation system. The computers decided it was an emergency. They woke the crew up early. We brought the ship in.

“We didn’t have time to wake up any other people. But we did have time to check the messages that had been coming in from Earth. They were crazy.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“I mean exactly that. The messages are crazy. Earth has changed a lot.” He paused. “We thought history would stop because our lives had stopped, because we were sleeping a magic sleep like children in a fairy tale.

“Not true. History went on and took a turn…” He paused again. “Progress is not inevitable. That is an error the vulgar Marxists make. I’ve always liked that term. I imagine a man with a big thick beard, farting at the dinner table as he explains commodity fetishism or the labor theory of value. And of course he gets the theory wrong.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

“Progress. There is no law that says humanity has to evolve ever higher social forms. Collapse is possible. Regression or stagnation. That’s essentially what happened after the twentieth century. Not regression but stagnation. We thought it was a characteristic of post-capitalist societies: extreme stability, as opposed to the extreme instability of capitalism, the crazy rate of change during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

“I think now the stability came from the terrible mess created in the twentieth century, the lack of resources and precarious state of the environment. We spent two hundred years cleaning up—trying to return the planet to its former state, trying to undo what those creeps and epigones had done. We didn’t have time for innovation.”

“We built the L-5 colonies,” I said.

“And the ship,” said Derek.

“Those are new objects. I am talking about new ideas. Most of our ideology and technology comes—came—from the old society. Most of what we have done is based on what people already knew prior to the collapse.”

“That isn’t entirely true,” I said.

Agopian said, “It is mostly true. We have been like the people of the early Middle Ages. We used the old knowledge in new ways. But we did not add to it.”

Derek frowned. “I question that analogy.”

“I don’t want to argue about the Middle Ages.”

Derek made the gesture that meant “forget what I said.”

“In any case, the stability—or stagnation—was only temporary. That’s what we learned when we woke up and listened to the messages from home. About the time we left, the various societies on Earth began to change rapidly.”