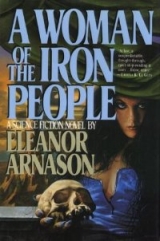

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

Derek and I stopped. The two natives rode up on either side of us and reined their animals. I looked at the bowhorn’s rider.

A male, almost certainly. He was wide and tall with dark, shaggy fur. His tunic was like the one I had on: cream-colored with geometric embroidery. On his arms were thick gold bracelets, and he wore a necklace of gold and amber.

He looked us over calmly, then spoke in the language of gifts. “I see that you have met my sister.” His voice was deep and soft.

“Inahooli,” Derek said.

The man made the gesture of assent. “I am Toohala Inzara of the Clan of the Ropemaker and the People of Amber.” He waved to the north. “My brother Tzoon is off in that direction. I haven’t seen my brother Ara for a couple of days. But he is out there somewhere, probably to the south. How is our sister?”

“As well as can be expected,” Derek said. “She has been alone for a long time.”

The man made the gesture of agreement. “She has always been edgy and hard to get along with. I was hoping her temperament would improve, now that she has—at long last—achieved something of importance. But it hasn’t?”

“No,” said Derek.

“Aiya! Such a difficult person! If you don’t mind, I’ll be going. I don’t like being with so many people. And two of you—I have to say it—are very odd-looking. That makes me even more uneasy.” He looked us over again. “It’s too bad Ara didn’t see you. He is the curious one.” He turned his animal off the trail and rode around us.

Derek started walking, more quickly than before. The rest of us followed. After a while Derek said, “He’s going to visit Inahooli. Is that possible?”

“No one among my people would do a thing like that,” said Nia. “Though I went to find my brother years ago.”

The oracle said, “I visit with my mother from time to time. But I am holy and a little crazy as well. An ordinary man would not go looking for his relatives.”

“This man must not be ordinary,” Derek said. “He will reach the lake tomorrow in the afternoon and find the grave. What will he do then?”

Nia made the gesture of uncertainty. “I do not know.”

“He was huge,” I said. “Are most of your men that big?”

“No,” said Nia.

“Thank God,” said Derek. “I was beginning to think of meeting three brothers the size of gorillas and trying to explain to them what happened to their sister.”

“As big as what?” asked Nia.

“Gorillas. They are relatives of ours, but much bigger than we are.” Derek was still walking quickly. “He’ll be a couple of days behind us when he starts.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

“Inzara. If he decides to come after us. Maybe three days, if we’re lucky and he spends time at the lake. Nia? How fast can a bowhorn travel?”

“The Amber People follow the herds. They understand animals and they understand patience. He will know better than to push his bowhorn too hard. Most likely, he will keep to a pace that is twice ours.”

“I used to hate problems like this. Bob has twice as many pieces of fruit as Alice, who is half again as tall as Krishna. How many days until Inzara catches up with us?”

“What is he talking about now?” asked the oracle.

“Nothing important.” I thought for a while. “It’ll take him two days, Derek. We ought to start worrying in the evening of the day after tomorrow. No, the day after that.”

“Okay. We are going to move as quickly as we can. Maybe the river is closer than we think.”

“Are you frightened?” I asked.

“Yes, of course,” he said in English. “If we kill any more natives, we are going to end up on the ship—cleaning out sewer lines, most likely. Or maybe cleaning cages in the laboratories. Anyway, we’ll be finished down here forever.” He glanced at me. “I bend rules a lot, and I operate close to the edge. But I have no intention of getting myself in serious trouble.”

“Why do you bend rules?”

He laughed. “To prove I can.”

We traveled till sunset, then made camp. The clouds parted and the Great Moon shone down on us. It was a little past full. Derek peered up at it. “The eruption must have ended.”

“Uh-huh.” I got out my one remaining human shirt and looked it over. A little dirty and with one tear. I decided to put it on.

“It’s too late,” said Derek. “That man has already seen Inahooli’s shirt.”

“Nonetheless…” I changed into my shirt and folded Inahooli’s, putting it away.

My radio rang. I turned it on.

“First the good news,” said Eddie. “The committee has decided to approve—with regret—your action in relation to Inahooli. You had no choice. Maybe if you hadn’t been half-unconscious, you could have figured out another way to stop her. But it was her fault that you were in no condition to think. Her karma was working itself out. There should not be any increase in your karmic burden, at least in the opinion of the committee.” I could hear a certain aloofness in his voice. Eddie had nothing against the various Asian religions—in their place, which was not a committee in charge of establishing policy for a scientific team. “Nothing bad is going on your record.”

I felt my body relax. I let my breath out in a sigh, then rubbed the back of my neck. “Okay. What is the bad news?”

“There are three pieces. Derek got a reprimand for that silliness about the bracelet.”

I looked over at Derek. He shrugged.

“However, that is not going to slow down anyone with his list of publications. The second piece of bad news is—the committee has decided to recommend a shipwide discussion of our policy re the natives.”

“Nonintervention?” I asked.

“Uh-huh.” Eddie sounded grim. “They want to reopen the question. I really would like you up here, or at least I would like the option. And that brings me to the third piece of bad news. Lysenko has gone over all the information we have about your part of the continent. The nearest place he is willing to land a plane is to the west of you. It’s a river that widens into a lake. He says it’s not good, but it’s possible.”

“How far?” I asked.

“Our best estimate is eight days. I am going to try to stall the first meeting of the all-ship committee.”

“That isn’t the worst of it, Eddie.”

“Oh, no? What is?”

“We met a native today. Inahooli’s brother. He is going to visit his sister.”

“Does he know you met her?”

“I had on a tunic that belonged to Inahooli. So did Nia. He recognized the clothes. That didn’t bother him. The natives are always exchanging gifts. But when he finds the grave…”

“Oh, damn.”

“And he has two brothers. They are traveling together or—at least—in the same direction. We may have three large angry natives after us.”

Eddie was silent for a minute or two. “What do you plan to do?”

Derek said, “Run like hell and hope they don’t follow.”

“I guess that’s the best idea. The committee is right about one thing. There have been too many incidents. I can’t figure out why.” Eddie sounded plaintive.

“You aren’t thinking,” Derek said. “Consider the people who’ve been having all the trouble. Me.

Harrison. Gregory. All men. We all ran into the same problem: the social role of adult males. I don’t know how Santha managed to avoid trouble. Do his people allow men into their village?”

“Now, that is an interesting story,” Eddie said. “But it is pretty long, and diagrams help a lot. I’ll tell you about Santha when you get back up here.”

“Okay,” said Derek.

“I’m not sure your explanation works. What about Lixia? Why has she had so much trouble?”

“Remember her traveling companions. Two men and a woman who has a widespread reputation for perversion.”

There was a silence. “You’re right, aren’t you? This is my mistake. I should have pulled Lixia out after the fiasco in that first village and reassigned her, maybe to the other continent.”

Derek made the gesture of uncertainty, then said, “I don’t know. I am not crazy about second-guessing history. And I don’t like words like ‘should.’ ”

“Well, do the best you can. Lysenko will be waiting when you reach the lake.”

Derek turned off the radio. “Do you notice how much Eddie uses the first person singular? The way he talks, he is the one who makes all the decisions and takes all the responsibility with no help from the rest of the committee.

“I, me, my, mine—

Each one a danger sign.

“That’s what the witches used to tell us. Listen for those words, they said. If a person uses them too often or with too much emphasis, then he or she is sinking down into the well of self. And that is a dangerous situation. You may be face-to-face with a greedhead or a power freak.”

I made the gesture of acknowledgment. I didn’t want to discuss the social theories of the California aborigines—not in English in front of Nia and the oracle. It was rude. I looked at Nia. “Our friend, the one whose voice is in the box, is worried about the amount of trouble we’ve encountered.”

“It is never easy to travel,” the oracle said. “I know that. One of my sisters is a great traveler. She has been as far north as the men go and met the Iron People in their summer range. She has been south as well and seen the ocean and gotten gifts from the people who live there: the Fishbone People and the People of Dark Green Dye. My mother has told me about her adventures. Hola! What a tale!” He bit one of his fingernails. “What does your friend expect?”

“A good question. I’m not entirely sure.”

For the next three days we traveled as quickly as possible. Nothing much happened. The sky was mostly clear, and the land rolled gently. We saw animals in the distance: flocks of grazing bipeds and once a solitary animal that Nia said was a killer of the plain.

“A male. See how big he is and how he shambles?”

“Nia, that thing is a black spot to me. I thought it might be a person.”

“What eyes you have! It is certainly a killer and a male. A female would be traveling with her children. The children would be hungry, and she would be dangerous. But a male is not much of a problem.”

“You say that!” the oracle put in. “I know better.”

“You were alone and had no fire.”

“We’ll make one tonight,” said the oracle.

This was in the middle of the third day. By then we were all getting uneasy, looking behind us and around us.

We stopped early atop a rise that was higher than the other little hills. Derek peered east. “Nothing,” he said. “I can’t see them. But nonetheless, we are going to keep watch. And I don’t think I want to risk a fire.”

“We have to,” Nia said. “There are worse things here than men. I do not want to lie in the darkness and wait for a killer of the plain.”

“All right,” Derek said.

We built the fire and huddled around it. Derek took the first watch. I sat and worried. Finally, when I couldn’t stand the worry anymore, I called Eddie.

“Any sign of the three brothers?” he asked.

“No. And I don’t want to think about them. How are things on the ship?”

“Not good. Meiling went over to the opposition.”

“What?”

“She has filed a report against nonintervention. The natives are not fools, according to her. They have eyes to see and minds to think with. They know that she is something utterly different, something utterly outside their experience andthe experience of their ancestors. Hairless people are not mentioned in the stories about creation.

“Knowledge—by itself—is an intervention. Our presence changes the way the natives see the world. According to her, there is no way to study these people without causing change.”

“The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle,” I said.

“So I am told. I’m not an expert on the history of science. And I don’t think it’s possible to apply the laws of physics to the behavior of people. That is like Social Darwinism. A stupid and dangerous theory.

“Meiling says the policy of nonintervention does only one thing. It makes life hard for the workers in the field. They can’t trade information with the natives, and they can’t offer help. Simple medical care, for example.”

“I did,” I said. “When Nia got hurt.”

“I know. But that was only one person, and you and Nia were alone. It wasn’t as if you had set yourself up as the village doctor. Meiling wants to. She has medical training and worked in Tibet. We told her no. She is still angry.”

I thought of Meiling: thin and intense, a person who had trouble with detachment. Nonaction was not for her. She had no interest in the ideas of Lao Zi or the Buddha. She came from the second great tradition in China, that of Mao Zi and Men Zi and Master Kong. The tradition of social responsibility.

“She has a point,” Eddie said. “I know that nonintervention makes everything more difficult. And maybe it is a farce. Maybe there is no way we can avoid changing this planet. But the policy makes us go slowly. If we abandon it or even begin to modify it, then it’s only a matter of time—and not much time—before the planet looks the way America did in the nineteenth century. The natives will be knee deep in explorers and prospectors and Marxist missionaries.”

“Eddie, you worry even more than I do.”

“I’m not going to say wait and see. I’m going to do everything I can to make sure my predictions don’t come true.”

“Good night, Eddie.”

I meditated for a while, looking at the fire. Then I dozed, sitting in the half-lotus position. Finally Derek shook me.

“It’s your turn. I haven’t seen anyone.”

I kept watch until the middle of the night. Nothing much happened. Meteors fell, and a night bug came out of the darkness. It glided above the fire on huge pale wings. A moment later it was gone.

I woke Nia. She got up, groaning softly.

“I saw a bug this wide.” I held my hands forty centimeters apart. “Is that possible?”

She frowned. “Is that why you woke me?”

“No. It’s your turn to keep watch. Could the bug have been that big?”

“Yes.” Nia stretched and yawned. “Go to sleep, Li-sa. I don’t feel like talking.”

I did as I was told.

The morning was bright. Above us and to the east the sky was clear. The west was full of clouds. They were a kind of cirrus.

“New weather,” Nia said.

We saddled the animals and went on. I rode, as did the oracle.

The clouds spread east, covering the sky. By midmorning the sun shone through a white haze. Derek kept looking back. “Maybe they’ve decided to forget the whole thing,” he said at last. He didn’t speak with much conviction.

At noon we came to a valley. We stopped on the bluff above it. The bluff was low. The valley was shallow and not especially wide. A river ran through the middle of it, brown and slow. Monster grass grew on the banks. A new variety. The leaves were distinctly blue. The slopes of the valley were covered with the usual yellow vegetation. Here and there I saw patches of red: a plant I did not recognize.

The trail descended into the valley. We followed it over the yellow slopes. I saw animals: a herd or flock of quadrupeds. They were tiny, no more than a meter high, and shy. As soon as we came near they bounded away in great leaps like so many gazelles. They were brown with white stripes down their backs, and they looked furry.

“What are they?” asked Derek.

“Silverbacks,” Nia said. “In the winter they turn entirely white, and their fur is warm and thick. Some people keep them. The People of Fur and Tin, for example. But we—the Iron People—think they are more trouble than they are worth. They do not keep their horns, but drop them every fall and grow new ones in the spring. While the horns are coming in the animals are irritable and hard to manage. They rub their horns against anything they can find: tent poles and the wheels of wagons and even the tripods we use to hang up cooking pots.”

The trail went along the river. Bipeds with long necks grazed on the leaves of the monster grass. They were almost the same color as the grass. In the shadows, among the blue leaves, they were hard to make out. Often I did not see one until it moved, reaching up a long thin arm to grab some food or twisting its neck and cocking its tiny head in order to stare at us. And I had no idea how many there were. Two? Three? A dozen?

“We don’t have to worry about killers of the plain,” Nia said. “There are too many animals around. They aren’t smart—these creatures—but they wouldn’t stay if they saw one of their kind being eaten.”

We continued along the river all afternoon. Gradually it widened, growing increasingly shallow. There were sandbars and patches of reed. The trail ended. We came to a halt.

Nia stared at the river. “This is the ford.” She shaded her eyes. “There is a man on the other side in the shadows. He is standing watching us.”

Derek shaded his eyes. “You’re right. Goddammit!”

Behind us a voice spoke. “That is my brother Tzoon.”

I looked around. A man stood five meters away from us, next to a stem of monster grass. Inzara. I recognized the tunic.

“And that is Ara.” He waved and a man stepped onto the trail we had just come down. He was as big as Inzara. His tunic was blue and covered with embroidery. He wore a belt made of linked copper and a knife in a blue leather sheath. His boots were blue leather. Around one wrist he wore a dozen or so bracelets of copper wire. He moved his hand slightly, gesturing to his brother. I heard the bracelets chime.

“What do you want?” asked Derek.

“You killed Inahooli,” Inzara said. “We dug her up. There was a deep wound in her back.”

Derek said nothing.

After a moment Nia said, “Yes. We did. What about it?”

“We want an explanation.”

Ara said, “The ceremony to honor the Ropemaker is ruined. We are men. We don’t care about these things as much as the women do. But it is no good thing to see the clan of our mother embarrassed.”

“Inahooli will be known as the guardian who failed,” Inzara said. “Her ghost will be furious. She was never easy to get along with. Now, who knows what she will do? There will have to be ceremonies of aversion and ceremonies of purification.” Inzara paused.

Ara continued, “And ceremonies to drive away the anger of Inahooli and of our ancestor the Ropemaker. This is a bad situation. We want to know how it came about.”

“All right,” Nia said. “We will tell you. Does the other one—the one across the river—want to hear?”

“Yes.” Inzara waved and shouted.

The third brother appeared a few minutes later, riding out of the grove into sunlight. He led two bowhorns with empty saddles. They forded the river, splashing through the shallows. When they reached our side, the man reined his animal. “Well?” His voice was as deep as Inzara’s but much harsher.

“Tie up the animals,” Inzara said.

Nia looked at me and the oracle. “Get down, both of you.”

We dismounted. Nia took our reins and led our animals into the nearest grove. The third brother rode after her.

They came back together, but walking some distance apart. Both of them looked wary. Nia was a big woman. The man dwarfed her. He was as huge as his brothers. He wore a kilt of dark green fabric and a yellow belt. The buckle was silver. His boots were green leather. On his broad chest he wore a necklace. It was tangled in his shaggy hair and more than half-hidden. I made out beads of silver, long and narrow, alternating with round amber beads as yellow as butter.

Inzara waved at him. “This, as I told you before, is my brother Tzoon.”

The man looked at us, then grunted. “Unh!”

“Who are you?” asked Ara. He had remained to the north of us on the trail. Inzara was a little to the south, close to the bank of the river. The third brother was to the east, at the edge of the grove. We were surrounded. Trapped.

Nia scratched her nose. “Will you answer a question for me? Then I will tell you who we are.”

Inzara made the gesture of assent.

“Why do you travel together?”

“We are not ordinary men,” said Inzara. “We were born together, all three of us in one birth.”

“Aiya!” said the oracle.

Nia said, “Hu!”

“No one in our village had ever seen a thing like that. Two children at once, yes. That has happened, though not often. Usually the children are small and weak. They die. But three—that was unheard of. And we were all large and healthy. People said our mother must have met the Trickster on the plain. We had to be unlucky. No woman could nurse three children. One of us, at least, would have to die.”

Ara continued the story: “Our mother said we were all fine babies. She couldn’t decide which one of us should be carried out on the plain and left for scavengers to find. She wanted to keep us all. Our mother never liked any kind of waste.”

The third brother—Tzoon—made the gesture of agreement.

Ara went on. “Our mother took gifts to the shamaness: a fine long rope and a piece of cloth covered with embroidery.”

“And a pot made by the Iron People,” Inzara said. “She was never one to keep things hidden in her tent. She knew the importance of giving.”

Ara made the gesture of agreement. “She asked the shamaness to perform the ceremony of interpretation. This took three days. Our mother nursed us as best she could. On the second day of the ceremony, when the shamaness was in a deep trance, our aunt Iatzi lost her baby.”

“It had always been sick,” Inzara added.

Once again Ara made the gesture of agreement. “It was her first child. Now her tent was empty and she had plenty of milk. She offered to help our mother.

“Our mother said that proved we were not unlucky. In fact we were luckier than most, since what we needed came to us.”

Inzara said, “When the shamaness woke, she told the villagers she had gone up into the sky and met the Ropemaker, the Mother of Mothers, and the Master of the Herds. They told her, ‘These children belong to us, and we will provide for them as we see fit. If we intend them to live, they will live. If we decide it is time for them to die—together or each one separately, you will see the result. Do not interfere and do not presume to understand our intentions.’ That was the end of her vision.

“What else is there to say? When we were children, we liked to be together. We almost never argued. There were people in the village who said we had only one spirit among the three of us. Maybe they were right. We don’t know. There are differences among us. Tzoon is silent. Ara is curious. I am unusually even-tempered. But it is true we are as close as sisters, and each one of us knows what the others are thinking. We went through the change at the same time exactly.”

“Even then,” Ara said, “we didn’t quarrel, though Tzoon became more silent than before.”

I looked at the third brother. He frowned.

“In the Summer Land and when the herd is moving, we stay close together. We like to look around and see a brother off in the distance. And we like to meet now and then to share food and talk. Inzara and I talk. Tzoon listens.”

The third brother said, “In the spring we stay apart.”

Inzara made the gesture of agreement. “We do not know what would happen then. What if a woman came out of the village full of lust, and two of us saw her? Would we fight? That would be terrible!”

“We make sure our territories are widely separated, though all equally close to the village,” Ara said. “This has become difficult in recent years. We are all big men, and the territories we have now are almost in the village.”

Inzara said, “We let other men—men we could face down—creep in between us. We lose some women that way. But our mother always said, ‘Nothing is gained by greed.’ ”

“Now,” said Tzoon. “Tell us who you are.”

Nia pointed at each one of us and gave our names. She gave her name last.

“You are the woman who loved a man,” Inzara said.

Nia made the gesture of agreement.

“And now you travel with another man.” He pointed at the oracle. “And with two people who have almost no hair.”

“Yes.”

“What sex are those people?”

“One is a woman. The other is a man.”

“Aiya!” said Inzara.

Tzoon made the gesture that meant “no matter.” “This is no concern of ours. If they want to risk bad luck—well, let them. They do not belong to our village.”

Ara made the gesture of agreement. “Our concern is Inahooli. How did she die?”

Nia rubbed the back of her neck. “This is not easy to explain.”

Tzoon frowned.

She glanced at him, then at his brothers. “First of all, we met with a shuwahara.A male with a family to protect. He frightened our bowhorns, and they ran away. We were stuck on the shore of the Lake of Bugs and Stones. This is important for you to know. We had no way to escape Inahooli after she went crazy.”

“Ah,” said Inzara.

“The first time she came, Li-sa and I were alone. She wanted to show off her tower, and Li-sa was curious. She is a peculiar person, always asking questions, like a little girl, poking at things and prying them open and asking and asking. Aiya!”

Ara frowned. “Anything can be taken too far. But there is nothing wrong with curiosity.”

“Anyway,” Nia said. “Li-sa went to see the tower. Then Inahooli decided she was a demon and pulled out a knife. She tried to kill Li-sa. But Li-sa got away.”

“Why did she think that one was a demon?” Ara waved at me.

Nia paused, frowning. She bit her thumbnail. “Inahooli remembered who I am. And she thought a person without hair who travels with a pervert must be a demon.”

“That makes sense,” said Tzoon.

Inzara made the gesture of disagreement. “The tower is protected. The shamaness performed ceremonies in the spring after it was built. There is magic all through it, woven into every piece of rope and around every piece of wood.”

“Does the magic protect it against everything?” I asked.

“No. Of course not. A high wind can blow it down, and hail can tear the banners. Animals can chew on it or perch on it and cause damage. But the tower ought to be safe from demons. If that one”—he pointed at me—“was able to get near the tower, she isn’t a demon. Though she might be something else unlucky. A person in need of purification, for example.”

“No,” said Nia. “Inahooli was definite. Li-sa was a demon. Inahooli decided the tower was ruined. Li-sa had taken away all of its power. She came to our camp at night, planning to get back at us in some way. That one”—she pointed at Derek—“saw her coming. He fought with Inahooli and won. He tied her up, and we tried to talk with her. They—the others—tried to talk with her. I was on the plain, looking for our bowhorns.”

“I will tell this part,” the oracle said. “We talked and talked, trying to convince her that we had done nothing to her tower. I understand these things. I am an oracle and the holiest person among the Copper People of the Plain.”

“Aiya!” said Inzara.

“Oracles don’t travel,” said Ara. “Why are you here?”

“My spirit told me to go with these people. They are important in some way or other.”

Ara looked at me and at Derek. He made the gesture of doubt and then the gesture of agreement. Together, they meant “if you say so.”

The oracle continued: “In the end Inahooli decided that the cause of all her trouble was your shamaness. She had put a spell on Inahooli and made her believe the tower was ruined.”

Tzoon grunted. “I never liked the shamaness. I remember what she was like as a girl. Always talking. Always being clever.”

Inzara frowned. “Why would the shamaness do a thing like that?”

“Inahooli said she used to belong to the Groundbird Clan, and they are rivals of your clan.”

I added, “She told us—the big moon was involved.”

Inzara looked at me, frowning. “The moon? How?”

“It was boiling over then.”

“We know,” said Ara. “We saw it, but that has nothing to do with the making or unmaking of towers. That means we are going to be short of food in the winter.”

“The old women say,” Tzoon added.

Inzara made the gesture of disagreement. “Inahooli was not telling the truth. The moon had nothing to do with what was happening, and our shamaness is the daughter of the old shamaness. A true daughter, born out of the old woman’s body. She has always belonged to the Clan of the First Magician.”

Ara said, “The mother of the old shamaness was born in the Clan of the Groundbird. She was adopted by the shamaness of that time, who had only sons. Some people said that she—the mother of the old shamaness—favored the Groundbird Clan more than she should have. But that was three generations ago.”

“Well, then,” the oracle said. “Inahooli was lying. We believed her and let her go. She came back at night and attacked us. In my opinion she was crazy. She fought without caring what happened. She almost won. But one of us managed to stab her before she killed all of us. That is what she was trying to do.”

“That is the whole story,” Nia said.

There was a silence. The three brothers were frowning.

“Well?” said Tzoon at last. “Are they telling the truth?”

Inzara made the gesture of affirmation. “It sounds like Inahooli. Deep inside her, she always believed things would go wrong for her. She looked for bad luck. When that one arrived”—he waved at Nia—“she must have thought, this is it. The thing I have been waiting for. The thing that will make me fail.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

“I’m thirsty,” Inzara replied. “Let’s drink from the river and then sit down. I will tell you about Inahooli.”

“All right,” said Nia.

The three brothers drank, kneeling one by one at the edge of the river. As one drank, the other two kept watch, glancing at us and the grove of monster grass and the far side of the river. Tzoon was the last to drink. He rose and wiped his mouth. “Unh!”

Inzara moved away from the bank. He sat down with his back against a stem of monster grass, stretched out his legs, and rubbed one thigh. “It was a hard ride from the lake. We had to rebury Inahooli and do it the right way, with singing and with gifts of parting. All that took time.”

Ara sat down at the edge of the grove, not far from Inzara. He folded his legs into a half-lotus position. “We could not do the entire ceremony. A shamaness is necessary for that. But we performed the parts we could remember from when we were children in the village.”

“Tell the story,” the third brother said. He remained standing on the bank of the river. How tall was he, anyway? Over two meters. In the sunlight his fur was dark brown instead of black. There were reddish highlights in the fur. His eyes were partially closed. The pupils had contracted to lines. The irises were pale yellow.

Inzara pointed at the ground, and the four of us sat down. We were facing Inzara and Ara. Tzoon was behind us. There was no way to watch him and his brothers at the same time. If anything went wrong, if the brothers became angry, he would be on us before we could rise and turn.