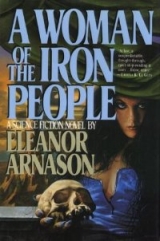

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

“Inahooli was the first born,” Inzara said. “The oldest daughter. She should have been the most important child. But we came next, and we were magical.”

“Ah,” said Nia.

Inzara made the gesture of affirmation. “Everyone watched us. Everyone talked about us. We were the important ones.”

Ara said, “I used to wonder why she looked unhappy. But I couldn’t ask her. It was never easy talking to her. She was quieter than he is.” Ara waved at Tzoon. “And she had a bad temper. Either she said nothing or she yelled and jumped up and down.”

“I never noticed that she was unhappy,” Inzara said. “But I have to say I never paid much attention to her. I was happy with my brothers and our mother and Iatzi.”

Behind us Tzoon grunted. In agreement, I decided.

Inzara went on. “I met Inahooli again—for the first time since we left the village—the spring before last. I had a territory close to the village in between two men who were getting old. They no longer had the strength for confrontation, not with me or Ara or Tzoon. But we let them in, so we would be safe from one another.

“The first woman who came into my territory was Inahooli. She looked good. She was an impressive woman. And I was glad to see her. She was my sister, after all. We had shared the same tent and the same fire. I thought, this is good luck. I will be able to ask about our mother and about Iatzi.

“But the moment she saw who I was, she became furious. ‘Can’t I ever get away from you?’ she yelled at me. I was surprised.

“We mated—”

“Why?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Why did you mate, if she was angry with you?”

“Because that is what a man and woman do when they meet in the time of mating.” He spoke slowly and clearly, as if he were talking to a child. “Unless, of course, they are mother and son.”

An incest taboo, I thought. Why? Maybe to protect young boys from their mothers. Was that possible? Or maybe to allow the men one relationship that was not sexual.

“Go on,” said Ara. “Tell the rest.”

“After we mated, I asked her why she was angry. She said I was a child of the Trickster, born to cause trouble. She had waited and waited for the change. She had given us—all three of us—fine gifts and told us good-bye. At last, she told herself, she was out of the shadow and into the light. We were gone. She was free of us. But we wouldn’t leave her alone. Every spring, Inahooli said, the women asked, ‘Who has mated with Inzara and Ara and Tzoon? Are they all right? Did they make it through the winter? Are they as lucky as they have always been?’ ”

“Unh!”

I looked around at Tzoon. His eyes were almost entirely closed, and he looked as satisfied as a cat in a patch of sunlight. Nothing wrong with that, I told myself. Everyone enjoyed appreciation.

Inzara continued: “Her luck was always bad, she told me. Her children were ordinary. She had no special skill. No one respected her. She had no friends.

“I told her it wasn’t my fault. Then she hit me. I thought, she will make me angry. I got out a mating gift. ‘Get out of here,’ I told her. ‘If you still feel the lust, go east. Old Hoopatoo is there. He isn’t much good at confronting, but he ought to be able to mate.’

“She gave me a gift, then rode away. I did not see her again until I dug into her grave.” Inzara paused a moment. “The next spring I asked the women—the ones who came to me—how Inahooli was doing. She had gotten pregnant, they said. Her child had been born too early. It died. That was bad news. But there was good news. The clan had chosen her to be the guardian of the tower. She was a difficult woman, they told me, but impressive. Strong and forceful, and her family was respected by everyone. A good choice for the guardian, all the women said.

“I thought, Now she will have prestige. She will stop being envious.” He looked at us. “I do not like being on bad terms with anyone—except other men, of course. And even then I don’t want a serious quarrel. Everything will be fine, as far as I’m concerned, as long as they back down.”

Ara made the gesture of agreement. Behind me Tzoon grunted.

Inzara went on. “No man ever sees the ceremonies in front of a clan tower—not unless he is very old and has gone through the second change and chosen to return to the village. But now and then, men go to look at a tower—usually after the ceremonies are over and the tower has been abandoned. Most of the time, the tower had been damaged in one way or another, and the holy masks are gone. They are always destroyed after the big dance. I thought, I want to see this tower—our sister’s tower—when it is new. I talked to my brothers. They decided to come with me. We rode south ahead of the herd.”

“We lost nothing,” said Ara. “In the summer, in the north, it doesn’t really matter what kind of territory a man has. Some areas are more comfortable than others. This summer, for example, I had a stretch of river full of fish and an outcropping of rock where berry vines grew. A good territory! I enjoyed it, especially the berries. They were as big as the end of my thumb and juicy. But it wasn’t really difficult to ride away and leave everything to that fat fool Oopai. I knew he would sneak in the moment I was gone.”

“No matter,” said Tzoon. “When the herd reaches the Winter Land, we will be there. Then Oopai can remember his berries. We will be the ones who are close to the village.”

Ara made the gesture of agreement.

“In any case,” said Inzara. “We rode to the Lake of Bugs and Stones. We found our sister and we came after you.”

Ara repeated the gesture of agreement. For a moment or two there was silence. What was next? What were they going to do? I glanced at the two brothers in front of me. Their faces—dark and furry—told me nothing. I twisted around and looked at Tzoon. He frowned and scratched his forehead—a wide, low expanse, covered with fur. The ridges above his eyes were prominent. His eyes were deep-set, his nose was flat, and his cheekbones were broad. An almost perfect Neanderthal. I had seen people like him in dioramas in museums. No. I was wrong. His jaw wasn’t as heavy as the jaws of those museum people; and his forehead—though it was low—did not recede. From the look of it, he had a lot of forebrain. Whatever that might mean in his species.

He grunted and made the gesture that meant “so be it.” After that he walked past us, away from the river.

Ara got up and stretched. A moment later Inzara stood.

We got up, all four of us.

“What now?” asked Derek.

“We got the explanation we wanted,” Inzara said. “We don’t mind being around each other, but you make us uneasy. We will go. East of here, we saw tracks. A flock of shuwahara.Tzoon is a fine archer, and Ara isn’t bad. We will kill an animal—a young one, fat and tender—and roast it.”

“Good,” said Tzoon.

Ara said, “We will eat and then ride south and wait in the land of winter for the herd to arrive.”

They got their animals and led them onto the trail, mounted and settled themselves in their saddles. Like Nia, they slouched, looking relaxed and comfortable. They gathered their reins, turned their animals, and rode away. At first they were close together. But after a short while Tzoon turned off the trail, riding into the grove. I lost sight of him. A minute or two later Ara turned his animal into the grove and—like his brother—was gone from view. Inzara rode on alone. The trail curved. He rode around the curve and was gone.

Derek exhaled. “Thank the Holy Unity or the wheel of fate or whatever is responsible. I hate to admit it, but that trio frightened me.”

“Why?” asked the oracle. “They weren’t crazy. Only crazy men fight when there is nothing to be won—no territory and no women.”

Nia made the gesture of agreement. “They are big men. Those ones rarely go crazy. They know their own strength. They have the best of everything, and they know they are able to hold on to what they have. It is the young men in the hills who go crazy from frustration. Or the old men who have lost their territories.”

“I forgot,” a voice said.

I jumped. So did everyone else. We turned, all of us.

A bowhorn came out of the grove. The rider wore blue. Ara. The curious brother. He reined his animal and looked down at us.

“Yes?” said Derek. “What is it?”

“You two. The ones without hair. What are you?”

“People,” I said. “We come from a long distance away. In our land all the people are more or less like us.”

“With no hair?”

“Only on the head. And there are a few patches in other places.”

“Where?”

“Under the arms and between our legs,” I said.

“Aiya! You must get cold in the winter.”

“We wear more clothes than you do,” I said. “In the summer we take off almost everything, and we are probably more comfortable than you are.”

Nia made the gesture of disagreement. “In the summer you have no protection against the bugs that sting or bite.”

I thought for a moment. “We have ointments with aromas the bugs don’t like. We smear them on us, and the bugs stay away.”

“It sounds messy,” Ara told me. “Fur would have been better. And handsomer, too. Whatever spirit made you wasn’t thinking about what she was doing.”

“That often happens,” the oracle said. “The spirits are very powerful, but they aren’t always smart.”

Ara made the gesture of agreement. “You are right about that. Look at the Trickster. He thinks he is so clever. He runs around setting traps and telling lies. And what happens? He falls into his own traps half the time, and his lies get so complicated that he can’t keep track of them. That isn’t clever. It’s stupid-smart.” He paused. “What is the name of your people?”

“Humans,” I said.

He repeated the word. “What does it mean?”

“People.”

Ara frowned. “But what kind of people? What do you carry when you travel? What is your gift?”

Derek said, “At times we call ourselves Homo sapiens,which means the People of Wisdom.”

“Aiya! That is a gift indeed! Do you have any with you? Tell me something wise.”

Derek was silent for a moment. Then he looked pleased. He had come up with something. “If I tell you something wise, then you will have a gift from me. But I won’t have anything from you. So I will have given you something for nothing, which is hardly wise.”

“Ah,” said Ara. He scratched his forehead. “You prove yourself wise by telling me nothing. Is that what you are trying to say?”

Derek made the gesture of agreement.

Ara made the gesture that meant “no.” “Your answer is not wise. It is stupid-smart. You think the way the Trickster does. He worries about being cheated. He wastes his time looking for tricks and lies when there are none. ‘Those branches by the trail hide a trap,’ he says. ‘A deep hole or a noose tied to a sapling. I’m no fool. I will go through the field.’ And he leaves the safe way, trodden by people, and goes off to tangle himself in briers or to fall in a bog. If that is the best you can offer, I do not think your people are the People of Wisdom.”

I looked at Derek. His face was red. He opened his mouth, then closed it. He wasn’t going to argue with Ara. I could understand that. Ara was very large and not especially polite. Inzara was the one who liked to get along with people. Ara didn’t seem to care.

“Most of the time,” I said, “we call ourselves after the land we live in. Derek is an Angelino, because his people live near a place called Los Angeles. I am Hawaiian. I come from an island called Hawaii.”

That wasn’t exactly true. I was from the island of Kauai. But I didn’t know the word for a collection of islands. Herd? Flock? Heap? Arrangement? Gathering? Lacking the word, I could not say I was from the Hawaiian Islands.

Ara frowned again. “You have a lot of names for yourselves. Can’t you decide what you are?”

“No,” I said.

“Ah. Well, if I meet any more hairless people, I will ask them for a name. Maybe they will come up with a better answer than you have.” He turned his animal and rode off along the trail.

“I liked my answer,” Derek said. “I guess these people don’t appreciate wit.” He used the English word for “wit.” Was there a native word? I didn’t know.

Nia got the bowhorns. We mounted double, Nia behind the oracle, Derek behind me. In that way we crossed the river. At the deepest point the water came to the bellies of our animals. I had to pull my feet up in order to keep them dry. Derek didn’t bother. As usual he was barefooted. The water felt good, he said.

On the far side Nia and Derek dismounted. We found the trail. It went south and west along the river. We followed it.

Part Two

Tanajin

That evening we made camp in a grove by the river. We ate the last of our food.

Nia said, “Tomorrow I will hunt.”

Derek made the gesture of assent and then the gesture of inclusion. The two together meant “I will hunt, too.”

I thought of calling the ship. But I was tired and depressed and didn’t feel up to a conversation with Eddie.

Rain fell during the night. I woke and heard the soft patter on foliage above me. It couldn’t have been much of a rain. It didn’t get through the leaves. I listened for a while, then went back to sleep.

By morning the rain had stopped. But the sky stayed overcast. Nia and Derek took off hunting. The oracle and I continued along the trail. To the right of us were groves of monster grass. To the left was the river. It ran over yellow stones and through beds of dull purple reeds. Birds clung to the reeds and made gurgling noises.

I thought about breakfast. My stomach gurgled, sounding like the birds. “Tell me a story.”

“What kind?” asked the oracle.

“An important story. A story about something that matters.”

“I will tell you about the moon.”

“Which one?”

“The big one. It was not always up in the sky. It used to be down here on the ground. The Mother of Mothers kept it. It was her cooking pot. The pot was able to fill itself. It needed no help from anyone.”

I thought of asking him to tell a different story.

“People could eat and eat. When the pot was empty, the people would sit down and wait. In a little while the pot was full again, all the way to the brim. It held porridge in the morning. At night it held a tasty meat stew. The Mother of Mothers fed everyone who was hungry. Everyone who was in need of food was able to come to her.”

Too late. He was getting into the story. It would be rude to ask him to stop. My stomach made another gurgling noise.

“But the people became lazy and greedy. They thought if a village had that pot, no one in the village would ever have to work. So the fourteen kinds of people I know about all sent emissaries to the Mother. Each one said, ‘Give me your pot, for then my people will be happy forever.’

“The Mother said no. The emissaries became angry. They went off together and consulted.

“ ‘We will steal the pot, all of us together. When we have it, we’ll draw straws. Whoever gets the longest straw can take the pot home and keep it for a year. At the end of the year she must give the pot to whoever got the second longest straw. In this way we’ll share. Every village will have a good year, one out of fourteen.’

“They stole the pot. It wasn’t hard. The Mother of Mothers was not suspicious. Then they drew straws and the trouble began. The women with long straws were happy. The women with short straws were furious. They began to quarrel and shout. They even hit one another.

“The noise attracted the Spirit of the Sky, who was far above them. He flew down and grabbed the pot and carried it away—though I don’t know how he did it, since he has wings instead of arms. Maybe he grabbed the pot with his feet. There are women who say his feet are claws like the feet of a hunting bird.

“Then the Mother of Mothers said, ‘You see what being greedy gets you. I am going to put my cooking pot in a safe place, and I am going to punish all of you, so that—in the future—women will think twice before they bother the spirits.’

“She put her cooking pot in the night sky. It became the moon. And she put the emissaries up there as well. ‘Your punishment will be that your mission will never be completed. You will wander through the sky forever, unable to get my cooking pot and unable to go home. The people of the world will learn from this to be less greedy and to treat the spirits with more consideration.’

“Those women became the little lights that travel across the sky night after night. We call them the Wanderers or the Thieves or the Women Without Respect.”

The little moons, I thought. The captured planetoids. A very nice explanation, except we had counted only twelve little moons.

“You said there were fourteen emissaries,” I said finally. “But I have seen only twelve lights.”

“That is true,” said the oracle.

“What happened to the other two?”

“That is another story, and I don’t think a man should tell it to a woman.”

“Oh.”

“It is not decent.” He used the negative form of the word that meant “well done,” “well made,” “in balance,” or “appropriate.”

“Oh,” I said.

We rode on in silence. At last the oracle said, “I forgot one thing about the story of the cooking pot. If you look up into the sky, you will see the pot grow more and more empty night after night. And then—night after night—you will see the pot refill.”

“Who eats from it?” I asked.

“People aren’t certain. Maybe it is the great spirits, and maybe it is the people who die. They must go somewhere and when they get there, they have to eat.”

I made the gesture of uncertainty and then the gesture of agreement. That meant I agreed, but not with any enthusiasm.

“Now I am hungry,” the oracle said. “I should have told another story.”

“Do you want to? I’m willing to listen.”

“Not now. Maybe Nia will come back soon.”

She didn’t. After a while rain began to fall: a fine drizzle. We took shelter in a grove of monster grass. The rain grew heavier. Drops of water came down through the foliage above us.

The oracle said, “On a day like this, I remember the house of my mother.”

“You do?”

He made the gesture of affirmation. “I remember it was always dry, even when rain came out of the sky like a river—like the waterfall my spirit inhabits. Aiya! It was comfortable! The flap was up over the smoke hole, and the fire burned low. Raindrops hissed in. The smoke coiled around itself under the ceiling—like lizards in the late spring when they mate.” He paused for a moment. “When it was done coiling, the smoke would slide out around the lifted edges of the flap—the way the male lizards do when they are finished with their womenfolk and eager to get away but also tired.”

What a speech! Amazing how well people were able to speak in a culture without books or holovision. We—who valued the written word and the projected image—talked in grunts and avoided metaphors as much as possible.

I looked at the oracle. His shoulders were hunched against the rain. His tunic clung to his body. The fabric was so thin that it offered almost no protection. Poor fellow.

Something clicked in my mind. Why didn’t these people wear trousers? They rode astride. On Earth, through most of our history, trousers had been connected with the riding of horses. Cultures that traveled on horseback wore trousers. Other cultures did not.

The rule did not work for China. Everyone wore trousers there and had for centuries, but few people rode horses.

I had an idea that Chinese trousers had come from Central Asia. If that were so, I had my connection with horses.

There was another exception to the rule: the Indians of the North American plain. They had not worn trousers. But they did not have horses long, before they were overwhelmed by white “civilization.” Maybe they would have developed trousers in time. And they did wear leggings.

I looked at the oracle again. His fur was a protection, of course, but surely not for his sexual organs. I realized I was up against the time-honored question. What does one wear under a kilt? Or a tunic, as the case might be. I searched my vocabulary, trying to find the right words.

The oracle said, “The rain has stopped.” He touched his animal on the shoulder, and it moved out onto the trail. My animal followed. Maybe I’d better have Derek ask the question.

The rest of the morning I pondered on loincloths and shorts and bicycle pants and the problem of male fertility. If they mated only once a year, they could not afford a high rate of infertility. Maybe that was the reason they didn’t wear trousers. But surely the men were uncomfortable.

Derek and Nia returned early in the afternoon. They brought food: a blue biped. It was a little one: a cub or chick or fawn.

We stopped and made camp. The rain began again. Derek and I went looking for dry wood. I asked him my questions about clothing.

He laughed. “I guess I should have told you. I asked the oracle about that long ago. Some men wear nothing. Others wear something that sounds like a jock strap. And there are people in the south who wear shorts instead of kilts. He doesn’t know what they wear underneath.”

“A jock strap ought to have some effect on fertility.”

“I haven’t seen the garment in question,” Derek said. “I don’t know how tightly it fits, and we don’t know much about the physiology of these people. For all we know those things the oracle has aren’t testicles. Maybe he keeps his spermatozoa in his ears.”

I made the gesture that meant “no.” “It’d interfere with hearing. But—” I made the gesture of agreement. “We need to do more research.”

He grinned.

I added, “I think I’ll leave this particular problem to you.”

“Okay. There’s probably an article in it. ‘Variations in Underwear among an Alien Humanoid Species.’ The title isn’t quite right. It isn’t pompous enough. But it’s a beginning.”

“Do you always start with the title?”

“The title is very important, Lixia my love. And we had better get our wood before the rain gets any heavier.”

By the time we got back to the camp, Nia had finished cleaning the biped. It looked less alien without its feathers, though I couldn’t decide what it reminded me of. A rabbit? A monkey? We roasted it. It had a mild flavor, like chicken.

After dinner Derek called the ship. One of the computers answered. It had a female voice and a soft Caribbean accent. Eddie was busy, it told us. It would put our call through to Antonio. There were chiming noises, a whole series of them, then a beep.

Derek asked, “Where is Eddie?”

“At a meeting,” Tony said. “Drafting a manifesto.”

“Oh, yeah?” said Derek. “On what?”

“Need you ask? Nonintervention.”

“Let’s keep this brief,” I said. “The natives are here, and they aren’t comfortable when we speak a language they don’t understand.”

“Okay,” said Tony. “Give me your report.”

Derek told him about the three brothers.

Tony was silent for a while. At last he said, “You were lucky. We were lucky. If those men had gotten angry, we’d be up here arguing about how to pick up the pieces. And Eddie would be saying we shouldn’t intervene.”

“Yes,” said Derek. “Do you have any information on the rendezvous?”

“Uh-huh. Keep going. The river you’re following is a tributary of a much bigger river. When you reach it—the big river, I mean—turn downstream. The lake is south of you about eighty kilometers. The plane will land there, though Lysenko is still not happy. He keeps asking for a salt flat. We have told him beggars can’t be choosers. He says there are no beggars in a socialist society.”

“What?” I said.

“We think he was joking. Humor does not always cross cultural boundaries.”

Derek said, “I’m going to turn the radio off.”

“Good night,” said Tony.

Derek hit the switch. He yawned. “So much for that. Maybe tomorrow it’ll stop raining.”

It didn’t. We traveled through drizzle and mist. My body ached: mostly my shoulder and arm, but also much older injuries—a couple of root canals and the ankle I had broken at the Finland Station on my way to join the interstellar expedition. My first time in an L-5, my first experience with low g, and I decided to try the local form of dancing.

The valley grew narrow. I began to see outcroppings of rock. It was yellow and eroded. Limestone, almost certainly. We had passed out of the area of volcanic activity.

Most of the rock was high above us. The lower slopes of the valley were covered with vegetation. Not monster grass any longer. These were real trees. The bark was rough and gray. The leaves were round and green.

“It is going to be an early autumn,” said Nia. “They have changed color already.”

“Is that the color they will stay?” I asked.

She made the gesture of affirmation. “Some trees turn yellow after they turn green, but this kind changes no further. The leaves will be green when they fall.”

“Aiya,” I said.

Late in the afternoon we came to a place where the valley was very narrow, and the trail went under a cliff. There was an overhang. No. A shallow cave.

We dismounted and led our animals up a little slope to the cave. There were ashes on the floor and pieces of burnt wood.

“I thought so. We’ll stay here tonight.” Nia looked at Derek. “You get wood.”

Derek made the gesture of assent. He left. We unsaddled the bowhorns and led them down to the river to drink, then tethered them where they could graze. One of the animals was limping a little. Nia crouched and examined a hoof.

The oracle called, “Lixia! Come here!”

I went into the cave. At the entrance it was maybe fifteen meters wide and ten meters tall, but it narrowed rapidly, and the ceiling dropped until I had to bend my head. The oracle stood where the cave ended or seemed to end. As I approached him I felt a cold wind: air coming toward me. “This is a holy place.” He stepped to the side and pointed. I saw the opening: a meter high and half a meter wide. The wind came out of it. The oracle said, “The hair on my back is rising, and I have a queasy feeling in my gut. This is definitely a place that belongs to the spirits.”

“Can we stay here?” I asked.

“I think so. I felt nothing in the front of the cave.”

I looked at the hole. Once we had a fire going, I could make a torch. “Is it forbidden to go in?”

“I don’t know. The spirits in this land are not the ones I know.”

We returned to the front of the cave. Nia was there, dripping water. “Aiya! What a day!” She brushed off her arms and shoulders. “That hoof looks all right. The animal is tired and doesn’t want to travel in weather like this. Who does? Either she is faking or there is an old injury that I can’t see.”

Derek came out of the woods, his arms full of branches. He ran up the slope, slipping a couple of times in the mud, reached the cave, and said, “This was dry when I got it. Now—I don’t know.”

“I will find out,” said Nia.

She built a fire. I told Derek about the holy place.

“After dinner,” he said. “We’ll go and take a look.”

Nia looked up. “Can’t you learn? Remember what happened the last time you got curious about something holy. That crazy woman almost killed us.”

“Don’t you wonder about things?” asked Derek.

“No.” Nia rocked back on her heels. “I have learned more about strange places than I ever wanted to know.”

“What about strange people?”

She frowned. “I like Li-sa. I am glad that I met her. I was tired of living in the forest and I never really liked the Copper People.”

“What do you mean?” asked the oracle.

“I don’t mean your people. I have nothing against them. But I did not like the Copper People of the Forest.”

“Them!” said the oracle. “They are peculiar.”

Nia made the gesture of agreement. “It was good that Li-sa came and I had to leave. I might have stayed there my whole life. That would have been terrible!”

The oracle made the gesture of agreement.

“What about me?” asked Derek.

“I have not decided if I like you,” said Nia.

“No?” Derek looked hurt.

The oracle said, “I will go into the back of the cave. I am used to holy places, and my spirit will protect me.” He rummaged in one of the saddlebags and found a piece of meat. Cold roast biped. He bit into it.

“I won’t,” said Nia. “I have no spirit to protect me, and holy places have always made me uneasy. But it’s good that you are going. You can make sure that Deragu does nothing that he shouldn’t.”

The oracle chewed, unable to talk. But one hand made the gesture that meant “why do you think I am doing this?”

We finished the biped, got branches, and lit them. Derek led the way to the back of the cave. Shadows moved around us. Our torches flared and streamed in the wind coming out of the hole. Derek crouched. “A tight fit. I think I can make it.” He turned sideways and squeezed in. His torch was the last thing to vanish.

The oracle and I waited. I was pretty calm, I thought, but the oracle fidgeted. A nervous fellow. I bit a fingernail.

“It opens out,” said Derek. His voice echoed. “A lot.”

The oracle crouched. “I can see his torch. I am going.” He squeezed out of sight. A minute or two later he said, “Aiya!”

I glanced at the entrance to the cave. The fire burned brightly. Nia sat by it, hunched over, a dark shape. Beyond her was rain, a shining curtain.

I went in on my knees, remembering that I’d gone caving in college and had discovered that I was slightly claustrophobic. The claustrophobia was made worse by dark.

There was no darkness here. The torch blazed in front of me. Smoke blew in my face, making me want to cough or sneeze. The passage got narrower. My head brushed the ceiling, and my shoulders rubbed against rough wet stone.

“Hurry,” called Derek. “You’ve got to see—”

The passage widened. I felt space above me and stood, lifting my torch. Nothing was visible except the floor—it was covered with a film of water and shone dimly—and two points of light in the distance, the torches my comrades carried.

“Here,” said Derek.

I went toward the sound of his voice.

He stood by a wall, his torch held high. The wall was yellow limestone, covered with water. There were paintings on it. Animals. They were red and orange, dull blue, gray, and brown. I recognized the creature that had attacked us by the lake and the blue bipeds. Dinner.

People moved among the animals. They were stick figures, done without any detail, though the animals were carefully detailed. The people carried spears and bows.

“Hunting magic,” said Derek. He walked along the wall.

I saw more animals: birds. They looked as if they ought to be large. The legs were heavy, the bodies round and solid. They had thick necks and large heads. The mouths were full of teeth.