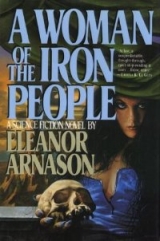

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

The women spoke with thick accents. They belonged to the Finely Woven Basket People, they said. A boat had come to their village out of the sky.

“Huh!” said Tanajin.

“I say it was a boat because it carried people.” The travel leader spoke. She was the largest of the women with a belly that made her look pregnant. But pregnant women did not usually travel. Maybe she was fat. Nia didn’t know a polite way to ask.

“It didn’t look like any boat I have seen. It looked like the birds that our neighbors make to hang on standards. The birds are gold. Their bodies are fat. Their wings are long and narrow. They have eyes made of various kinds of crystal.”

Another woman said, “This thing—this boat—had two large eyes in front that shone like crystal. There were other eyes—little ones—that went along the sides. Hu! It was peculiar.”

The travel leader frowned.

The other woman made the gesture that was an apology for interrupting.

The travel leader said, “The people in the boat had almost no fur. One of them spoke the language of gifts, though very badly. This person said they wanted to come and visit and exchange stories.”

Tanajin looked at Nia. “You weren’t crazy.”

“What does that mean?” asked the travel leader.

“There have been clouds in the sky. This woman said they were caused by boats that belonged to the hairless people.”

“How did you know?” asked a woman.

Nia said, “Finish your story. I will tell you later.”

“We didn’t know what to do,” said the travel leader. “Our shamaness decided to ask for advice. She sent us to the Amber People to ask for their opinion. Another group has gone to the Iron People and another to the People of Fur and Tin.

“We have a quarrel going with the Gold People. They’re our closest neighbors. They have tongues like knives and they like to make up satiric poetry. We aren’t going to ask them for anything.”

“Also,” said another woman, “they live in the high mountains. We don’t like going there. Hu! It is dark! The trail goes up and down!”

“We are people of the plain,” said the leader. “We like to be able to see all the way to the horizon.”

Nia made the gesture of agreement. “The Iron People have agreed to let the hairless people visit. I don’t know what the Amber People have decided.”

“That is how you know,” said the travel leader. “You have seen these people.”

“Yes,” said Nia. “But I had not seen the kind of boat you describe.”

The women asked questions. Nia said as little as possible. She didn’t want to describe the long journey from the east. She didn’t want to explain why she hadn’t been living with her own people.

“It’s obvious that you know more than you are telling,” the travel leader said finally. “That’s your decision and not our problem. We have been sent to the Amber People.”

The next day the women continued on their journey. Nia finished working at the forge.

“I’ve been waiting for this,” said Tanajin.

Nia made the gesture of inquiry.

“Ulzai keeps appearing in my dreams. He speaks urgently. I don’t understand him. Usually he is wet. That ought to mean he has drowned, but I don’t know for certain. What does he want? Why is he bothering me?”

Nia made the gesture of ignorance.

“I am going to make a new raft and float downriver. I’ll ask about him in the village of the hairless people. Maybe they have found his body.

“After that I’ll keep going. There is a village on the river below the lake. The people there never move. Their houses are wood. They are always in them.” Tanajin paused.

“Their gift is a certain kind of very large fish. They smoke it and pickle it. They also preserve the eggs of the fish and the stuff that the male fish produce. Their shamaness is famous for her wisdom. I’m going to ask her to explain my dreams. Maybe I need a ceremony of propitiation.”

“That could be,” said Nia. “What about the crossing?”

“People can do what they used to do before I came.”

“The crossing has been your gift.”

“You will continue traveling. That’s the kind of person you are. If I stay here alone, I’ll go crazy. I’ll find a new gift—maybe among the Fish Egg People, maybe farther south.”

Nia helped Tanajin build the raft. It took five days. When they were finished she said, “Teach me how to paddle.”

“Why?” asked Tanajin.

“I think I’ll stay here for a while. When people come, I’ll take them across. I’ll explain that you have gone, and that I will be leaving soon. The news will get around. People will know to bring axes with them.”

Tanajin made the gesture of agreement.

She stayed another fifteen days. They spent most of their waking time on the water. Nia learned how to swing the big heavy paddle and what lay under the surface of the river. There were islands that only appeared in the very worst dry years, but they were always there and the raft might get caught on one. There were logs—more than any person could count. Some floated on top of the water. Others floated underneath. Some had gotten caught in the mud of the river bottom and stood upright like living trees, their branches reaching toward the surface. Others were held less tightly by the mud and swung back and forth in the water.

“Like reeds in the wind,” said Tanajin. “Or a tree that is starting to break.”

“Aiya!” said Nia.

“Every kind of log is dangerous. If the raft gets caught, you may not be able to get free. Never let a rope trail. Always carry a knife. Always keep an eye on the surface. If there are swirls and eddies—avoid that place!”

“There is more to this than I realized,” said Nia.

Tanajin barked. “You people in the north are so ignorant! You think the river is like the plain. You think that everything that matters is on the surface, where any fool can see it.”

Nia kept her teeth clenched together. A teacher always had the right to at least a few insults. Everyone knew that. It was true among all peoples.

Finally Tanajin said, “You aren’t skillful yet, and you don’t know enough about the river, but I think you’ll be able to manage. I’ll leave you now.”

Nia made the gesture of acknowledgment.

The next morning Tanajin piled her belongings on the new raft. Nia helped push the raft out into the river. Tanajin climbed on and made the gesture of farewell.

Nia waved in answer.

The raft floated out. Tanajin began to swing the paddle. Nia watched. The woman grew smaller and smaller. At last she was gone. The raft became a dot on the wide and shining river. Nia shaded her eyes. The raft was gone.

She moved her belongings into the empty tent, but she didn’t sleep in it. It smelled of Tanajin, and the walls were braced with pieces of wood. They were too solid. A proper house ought to shift in the wind—not much, but enough so the people inside knew what was happening on the plain.

Every evening she took a blanket out front. She lay down by the fire and looked up. She began to notice things.

One was a light that moved like a moon, but was the wrong color: a silvery white. It followed a new trail, different from any of the old moons. Night after night it crossed above her. She had no idea what it was. Had one of the Two Lost Women come back?

There was a new star, too. It appeared in the same place every evening: at the center of the sky. The other stars moved around it. It did not move at all.

There were other lights: red and white and green. For the most part they were in the south, close to the horizon. They moved rapidly in all directions.

She became uneasy. It was one thing for the hairless people to make a new kind of cloud. There were a lot of different kinds of clouds, and they were always changing. One more kind wasn’t likely to cause trouble. But a new star! A new moon! Lights that wandered like bugs! Here! There! Up! Down!

Smoke rose on the far side of the river. She went over. A man waited there. A big fellow with iron-gray fur.

“Who are you?” he asked. “Where is Tanajin?” He spoke with an accent she did not recognize.

“She left. I am taking care of the crossing.”

“Huh!” the man said.

She took him across the river, along with two bowhorns. He gave her salt in a leather bag. The leather was thin and soft. She did not know what kind of animal it came from. The man did not explain who he was or why he was traveling through the land of the Iron People. Nia decided not to ask.

More days passed. The new moon kept traveling over. The new star remained at the center of the sky. Every few days she saw another one of the long clouds.

The Basket Women returned. Their leader said the Amber People had not been a lot of help. “They are busy performing ceremonies of aversion and propitiation. Something has gone wrong. They wouldn’t tell us what, except to say the Trickster was behind it.

“This is a spirit we don’t know about, though he sounds a bit like our Bird-faced Woman. A troublemaker! A sneak and liar! Though I have to say we owe a lot to the Bird-faced Woman. She gave us fire and taught us how to weave baskets.”

Another woman said, “We shouldn’t be too grateful. She convinced the First People that there was nothing wrong with incest. And she let the small black bug of death loose in the world.”

The travel leader frowned. “The Amber People kept going on and on about this spirit. This Trickster. They told us the hairless people are not the problem. The Trickster is the problem. He is the one who is making changes in the sky.”

“Have the hairless people paid a visit there?” asked Nia. She pointed east.

The travel leader made the gesture that meant “no.” “I’m not certain they believed us when we told them about the hairless people and the boat that was able to fly. Maybe they thought we were liars, like the Trickster.”

“Aiya!” said Nia. She took them across the river, then went back.

By this time the forest along the river had finished changing color. The trees were orange and yellow. The reeds in the marshes were red. Flocks of birds went overhead like clouds.

Nia began to worry about food. She was running out. Winter was coming. She made fish traps and set them in the river. Then she went into the forest, cut wood, and made a smoking rack. That was the safest way to preserve fish and meat. The smoke would hide the food aroma. The animals in the forest would not come looking for something to eat.

She made traps to set in the forest. Then she made a bow. It was the weak kind that people in the east used. But she did not have the materials to make a bow the right way out of layers of horn, and she wasn’t a bow maker.

How could men survive alone? A woman needed an entire village full of people with different kinds of knowledge.

“Well,” she told herself. “I know it is possible. I lived on my own before—except for Enshi, and he wasn’t all that much help. I can do it again.”

She gathered food. Clouds came out of the west, gray and solid-looking. They dropped rain on her. The rain was cold and heavy. Leaves came off the trees. They lay on the ground in the forest and floated past on the river. Red. Yellow. Orange. Pink. Purple.

The flocks of birds became less frequent. The bugs were almost gone.

Day and night she tended the smoking fire. Gray smoke twisted up into the gray sky. No animals came out of the forest to find out if she had anything edible. In this she was lucky. This was the time of year when every kind of thing looked for food—though not with desperation. Desperation would come later with the snow.

One afternoon Nia was in front of the tent, cleaning a groundbird. She cut the belly open and reached in, pulling out the guts. One of her bowhorns whistled: a sign of warning. She looked up. A rider was approaching, coming up the trail along the river. Nia stood up, holding the bloody guts. They were still attached to the bird, and when she stood she lifted the bird off the ground. For a moment it dangled at the end of a rope of guts. Then the rope broke. The bird fell. The rider reined his animal.

He was big and broad through the shoulders. His fur gleamed, even though the sky was dark and gray. His tunic was yellow, covered with embroidery. He wore gold bracelets and a gold fish-pendant that hung from a necklace of amber beads. “I heard the old crossing-woman was gone. The new one looks as if she belongs to the Iron People. She doesn’t speak much and tells nothing about herself.”

“Who can have told you this, Inzara?”

“The man whose gift is salt.” Inzara dismounted. “Why don’t you finish what you are doing, then wash your hands?”

He led his animal in back of the tent. She cleaned the bird and washed her hands in the river.

Inzara returned, carrying his saddlebags.

“What are you doing here? Shouldn’t you be in the Winter Land, protecting your territory?”

“My brothers will take care of it for me. It doesn’t matter this time of year, anyway.”

She spitted the bird and set it up over the cooking fire. Inzara crouched down. Aiya! He was big, even resting on his heels.

“It’s pretty obvious the world is changing. There is a new star in the sky and a new moon. A while back a young man came out of the village. I stopped him and spoke with him before I sent him on his way. He told me people had come from the far west, carrying their provisions in baskets and bringing a crazy story. Visitors came to them riding on a bird made out of metal. The visitors had no hair. The people from the west wanted advice. But my people were busy. They have been quarreling and performing ceremonies ever since they came to the Ropemaker’s island. The guardian of the tower was dead. The tower itself was damaged.”

“We did not touch the tower,” said Nia.

“Birds or the wind,” said Inzara. “In any case, the clans have been accusing one another of bad thoughts and magic. This is what the young man said. I could explain what really happened, but who listens to men about such things?” He paused. “I thought the world is changing, and it is obvious who is behind all the changes. The people without hair, the oracle, and Nia.

“The man who brings the salt came. He told me about the new woman at the river crossing. I thought, that is almost certainly Nia. How many strange women can there be, wandering around the plain?”

“That’s good thinking, but why did you bother? I don’t think I’m responsible for any of the changes, and if I am, there is nothing I can do about them now.”

“Are the hairless people responsible?” asked Inzara.

“Maybe. I think so.”

“And you are friends with them.”

“Maybe.”

“Tell me where you will be in the spring.”

Nia looked up, surprised. “Why?”

“You have a lot of luck—more than any woman I’ve ever heard of. I’m not certain what kind of luck it is. At times it seems more bad than good. But it is certainly powerful, and there is no question about my luck. It is always good.

“If you had a child, and I was the father—or Ara—or Tzoon, think of the luck the child would have! Think of the power!”

Nia felt even more surprised. Her mouth hung open. Her hands stayed where they were, on her thighs.

He went on. “We have talked it over, the three of us. If you are interested, we will draw straws. The one who gets the long straw will go to meet you. This area would be good. There aren’t likely to be any other men around. Or women. It’s easy to get distracted in the time for mating, and this is something that ought to be done the right way. Carefully.”

“No,” said Nia.

Inzara made the gesture of inquiry.

“I have done too many strange things already, and I’m getting old. I don’t think I want any more children.”

“You have children already? Are there any daughters? How old are they?”

Nia made the gesture that meant “stop it” or “shut up.”

“Why?” asked Inzara.

“This is crazy. Men don’t pick the women they mate with. Men don’t care who their children are or what the children are like.”

“What do you know about men? What does any woman know? You sit in your villages! You chatter! You gossip! You tell one another what men are like. How can you possibly understand anything about us? Have you ever spent a winter alone on the plain?”

“Yes,” said Nia.

He barked, then made the gesture of apology. “I was forgetting who you were.” He paused and frowned. Then he spoke again. His voice was deep and even. He didn’t sound the least bit crazy. “Tell me where you will be, Nia. Do you really want to mate with whatever man comes along? He might be a little man. He might be old or crazy. Who knows how the child will turn out?”

Nia looked at the bird cooking above the fire. The skin was turning brown. Liquid fat covered it and it shone. She turned the bird, then looked at Inzara. “I told you, I don’t want any more children. Also, I am tired of doing things in new and unusual ways. I want to be ordinary for a while.”

Inzara made the gesture that meant “that isn’t likely to happen.”

“Also, I don’t like other people making plans for me. I do what I want.”

“And you want to be ordinary,” said Inzara. He stood up and stretched. Hu! He was enormous! His fur gleamed in the firelight. So did his jewelry. “Will you take me across the river?”

“Why do you want to go?”

“The hairless people have built a village south of here on the Long Lake. I want to see it.”

“Why? You won’t be able to go into it.”

“Will the hairless people drive me out?”

Nia thought for a moment. “No.”

“I can endure people. Look at me now. I’ve been sitting and talking with you, and it isn’t the time for mating. If the village looks interesting, maybe I’ll go in. Ara wants information. I am the one who gets along with people, so I am the one who came. But he’s the one who’s curious.”

They ate the groundbird. Inzara took a blanket and went around the house. He slept on the ground next to his animal. Nia slept inside. She dreamt about the village of the hairless people. She was in it, wandering among the big round pale houses. Inzara was there, and other people she did not recognize. Some of them were real people, people with fur. Others were like Li-sa and Deragu.

In the morning she took Inzara across the river. “There is no good trail along the river. You will have to go west onto the plain and then south.”

He made the gesture that meant he understood.

She went back to the house of Tanajin.

More days went by. There was a lot of rain. Leaves fell. The sun moved into the south. When it was visible, it had the pale look of winter. It was growing hungry, the old women used to say, though that made no sense to Nia. The sun was a buckle. Everyone knew that. The Mistress of the Forge had made it and given it to the Spirit of the Sky. He wore it on his belt. How could a buckle grow hungry?

There was no one to answer her question.

A group of travelers came out of the west: Amber Women, returning home. They were quiet and they looked perturbed. Nia did not ask why. She ferried them. They gave her a blanket made of spotted fur and a pot made of tin.

The weather kept getting colder. There was ice in the marshes now. It was thin and delicate, present in the early morning and gone by noon. If she touched it, it broke. Aiya! It was like the drinking cups of the hairless people or their strange square hollow pieces of ice.

The sun moved farther into the south. The sky was low and gray. One morning she heard thunder, but saw nothing.

Another island, she thought. Going up or coming down. How many were in the lake now? Where did they go when they left?

Inzara returned. He built a fire. She went and got him.

“I couldn’t do it. I saw their boats and their wagons. I knew my brother would want to know more. But I wasn’t able to force myself to go in. Even after the man without hair invited me.”

Nia made the gesture of inquiry.

“The one I met before. Deragu. He found me on the bluff above the village. We talked. He said other people—real people—had come and looked at the village, but not come in. Not many. Three or maybe four. He asked me to give you a message.”

“Yes?”

“Come to the village for the winter. You gave many gifts to the hairless people, he said, especially to him and Li-sa. They have given you little. This makes them uncomfortable, he said. A wagon will not move in a straight line if the bowhorns that pull it are not properly matched. A bow will not shoot in a straight line if the two arms are not of an equal length.”

Nia frowned. “I don’t remember that I gave them anything important.”

Inzara made the gesture that meant “that may be.” “An exchange is not completed until everyone agrees that it is completed. It’s hard to say which kind of person causes more trouble—one who refuses to give or one who refuses to take.”

Nia said nothing.

Inzara went on. “I mated one year with a woman who did not like taking. It almost drove me crazy. Everything I gave her was ‘too much’ or ‘too lovely’ or ‘too good’ for her. As for her gifts, which were just fine, she said, they were ‘small’ and ‘ugly.’ I wanted to hit her. I got away from her as quickly as possible.”

Nia grunted.

Inzara said, “I knew the woman’s mother. She had eyes like needles and a tongue like a knife. Nothing was ever good enough for her. I think the woman learned to apologize for everything she did. Hu! What an ugly habit!”

They reached the eastern shore of the river. Inzara helped her pull the raft up onto land. He took off his necklace of gold and amber and held it out. Nia thought of saying it was too much to give in exchange for a river crossing. But Inzara looked edgy, and she didn’t want to argue with him. She took the necklace.

He mounted his animal and gathered the reins. He looked down at Nia. “I used to think that nothing frightened me except old age. But the village back there frightened me.” He waved toward the west and south. “I’m angry with myself and restless. I’d better get going.” He tugged on the reins. The animal turned. Inzara glanced back. “Maybe I will come again in the spring. Or maybe Ara will come. The village won’t frighten him. And Tzoon is like a rock. Nothing ever bothers him.”

He rode off. Nia put the necklace on. It was fine work. The amber was shaped into round beads, and the fish was made of tiny pieces of gold, fastened together. It wiggled like a real fish.

She walked back to camp.

The next day snow fell: large, soft flakes that melted as soon as they touched the ground. She packed her belongings and cleaned the house. She left a bag of dried food hanging from the roof pole. People might come. They might be hungry. She left a cooking pot, a jug for water, and a knife.

After that she took a good look at the bowhorns. Their hooves were healthy. There were no sores on their backs. They walked without favoring any foot or leg. Their eyes were clear. So were their nostrils. She found no evidence of worms or digging bugs.

Nia made the gesture of satisfaction.

Her hands were not entirely empty. She had three animals and food and the metal-working tools, which Tanajin had left. It was more than she had taken from the village of the Copper People. More than she had taken from her own village when she left the first time or the second time or the third.

The next day she crossed the river. She had to make two trips. The first one was easy. The air was still. The sky was low and gray, but nothing came out of it. She took two of the bowhorns and tied them on the western shore, then went back.

She loaded the rest of her belongings and led the third bowhorn onto the raft. It snorted and stamped a foot.

“Be patient! Be easy! The others gave me no trouble.”

She pushed off. Snow began to fall. The flakes were big and soft. They drifted down slowly. By the time she reached the first island the eastern shore was gone, hidden by whiteness. She crossed the island and loaded everything onto the second raft.

The snow was staying this time, sticking to bare branches, sticking to the gear the bowhorn carried: the bags and blankets. There was snow on Nia’s shoulders and snow on the rough bark of the logs that made up the raft. All around her flakes of snow touched the gray surface of the river and vanished.

Aiya! The whiteness! It hid the island she had just left, and she could not see the island that was her destination. Nia swung the paddle and grunted.

They landed at the far southern end of the island. Nia pulled the raft up on land, then looked at it. She ought to bring it upriver to the proper landing place. But that would take time, and the storm was getting worse.

“Let others deal with this problem,” she said.

She led her animal across the island to the final raft.

That crossing was easier. The channel was narrow. But the snow kept getting thicker. It covered the raft and the bowhorn and Nia. Even the paddle was covered with snow. When she lifted it and swung it, pieces of snow fell off. They made noises when they hit the water.

A poem came to Nia. She didn’t know if she’d learned it as a child or made it up right here in the middle of the river.

Why do you come,

oh, why do you come now,

O people of the snow?

People in white shoes,

why do you bother me?

She reached the western shore and led the bowhorn off, praising it for good manners. It snorted and flicked its ears.

“I know. I know. You wanted to make trouble. But you held yourself in check. That’s worth praising. It’s over now.” She looked at the river: the gray water and the falling snow. “We’ll pull the raft up onto land, and then we will go and find your companions. And in the morning we’ll go south.”