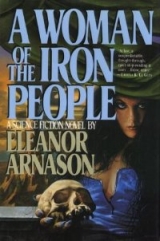

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

Nia

The hairless people left in the morning. The people of the village began packing in the afternoon. Nia helped Angai, but only with the things in the front room of the tent. The back room was the place where Angai kept her magic. Everything there was hidden by a curtain of red cloth embroidered with animals and spirits. The curtain went across the tent from top to bottom and side to side. Nothing came through it except the aroma of dry herbs and the feeling of magic. The feeling made Nia’s skin itch and prickle.

She stayed as far from the curtain as possible, kneeling by the front door in the afternoon sunlight, folding clothing, and putting it in a chest made of leather.

On the other side of the room Hua knelt. She was right next to the curtain, below a picture of a spirit: an old man, naked, with his sexual member clearly visible. His back was hunched, and he leaned on a cane. The Dark One, thought Nia, in one of her many disguises.

Hua had laid out tools and was counting them before she packed them: knives of many sizes, needles, spoons made of polished wood and horn.

Angai was behind the curtain, packing up whatever she kept there, objects that Nia did not want to see.

“How can you bear to stay here?” Nia asked.

Hua looked up and made the gesture of inquiry.

“By the curtain. In this tent.”

Hua repeated the gesture of inquiry.

“Nia has never liked magic,” Angai said.

“It doesn’t bother me,” Hua said.

“A good thing,” said Nia. “If you are going to be the next shamaness.”

“Of course I am,” said Hua. “Who else is there?” She was counting combs now. She laid them out, big ones and little ones, made of wood and horn and metal.

Nia realized her entire skin was itching. The feeling was especially bad between her shoulder blades and along her spine. “Keep some of those out. It’s a long time since I’ve had a grooming done the proper way—by a friend or a female relative.”

“All right,” said Hua. She put two of the combs aside: one of ordinary size and a big one with wide gaps between the teeth.

Nia made a satisfied noise. “It will be something to remember when I am out on the plain.”

“Aren’t you coming with us?” asked Hua. Her voice sounded sharp and high.

“No.”

“Why not? Has someone been giving you trouble? You aren’t worried about Anhar, are you? Hasn’t Angai told you that you can stay?”

Nia laid a tunic on the floor. It had long sleeves. She folded them in over the body of the tunic, smoothing the fabric. It was fine and soft, a gift from people living in the distant south.

“When I lived in the Iron Hills, I was with you and Anasu and Enshi. When I lived in the east, I was at the edge of the village, as far out as a man. I’m not used to being with a lot of people. I no longer know how to live in a village.”

“You never really knew,” said Angai through the curtain. “You always acted as if you were alone.”

Nia felt surprised. She made the gesture that asked “is that really true?” But Angai couldn’t see, of course.

Hua said, “My mother wants to know if you are certain.”

“Yes.” The curtain fluttered. Angai must have brushed against it. “I know you better than anyone, Nia. You are like a rock! You are like an arrow! You are what you are, and nothing can change you. You go where you go, and nothing can make you turn. You have never been an ordinary person.”

“I didn’t know that,” said Nia.

Hua said, “I wanted you to stay with us. I wanted to hear your stories.”

“I’m not going away forever. But I need time alone.”

Angai said, “This is the right decision. I’d like Nia to stay. But I’ve seen the way the people of the village look at her. She makes them uneasy. If she goes, they will settle down after a while. Then—I think—she will be able to come back. But if she stays now, they will get angry. Too much has happened. They have seen too much that is new. If she stays now, they will drive her off.”

Hua made the gesture of regret.

They kept working until the sky began to darken. Angai came out from behind the curtain. They ate dinner. Angai combed Nia’s fur. Aiya! It felt good! Especially when Angai combed the thick fur on her back. She leaned against the comb—the big one—and groaned with pleasure.

When that was done, they talked for a while. Nothing important was said. Angai described the trail that she wanted to follow going south and the place she wanted to spend the winter. Nia asked a question now and then. Hua listened in silence.

At last they went to sleep. Nia kept waking. The tent door was open. But there was little wind. The air in the tent was motionless and warm. She looked out the door. There were stars above the tents of her former neighbors. So many! So thick and bright!

They got up at dawn and began to load the wagon. Anasu brought the wagon-pullers in: six fine bowhorn geldings. They hitched them up. The sky was clear. The day was going to be hot. Nia could feel it.

Angai said, “I’d like you to go back out and get an animal for Nia. White Spot or Sturdy or Broken Horn, whichever you find.”

“Why does she need one?” asked Anasu. “I thought she was going to ride in the wagon.”

“She is leaving us,” Hua said.

“Why?”

“She wants to be alone.”

“Aiya! What a family I have!” He turned his bowhorn and rode away.

Nia asked, “Is he angry?”

“Maybe a little,” Hua said. “It has not been easy having you for a mother, even though Angai has protected us.”

Nia made the gesture of apology.

“It could have been worse,” Hua said. “We could have had Anhar for a mother. Or Ti-antai. A malicious woman. A woman who is a coward.”

“Is that what you think about Ti-antai?”

“Maybe she isn’t a coward,” Hua said. “Maybe she has a little mind. She never thinks about anything except her children and their children and the neighbors.”

“Isn’t that enough?”

“Not for me,” said Hua. “I am going to be a shamaness.”

“Then you can help me now,” said Angai. “I have many boxes full of magical objects, and they have to go into the wagon. Nia isn’t going to touch them. I know that.”

Hua grimaced and made the gesture of assent.

After the magic was loaded, they took down the tent. Nia helped. They loaded it into the wagon. By noon they were ready to go, and so was the rest of the village. Nia looked around. There wasn’t a tent anywhere in sight. Instead there were wagons and bowhorns, women lifting boxes, children running. A few wagons had begun to move. A cloud of dust hung in midair to the west of the village.

Anasu came back, leading a bowhorn: a large young gelding. There was a large white mark in the middle of its chest. The mark was curved like a bow. The grip was at the bottom. The two arms of the bow rose up on either side. The mark reminded Nia of other things as well: the emblem for “pot,” the emblem for “boat,” and the Great Moon when it was thin. If Angai had the animal, it must be lucky—though it worried Nia to look at the mark and see so many things.

“It’s five years old,” said Angai. “There is no better traveler in the herd. Be careful, though. Sometimes, not often, it gets a little edgy.”

“I have nothing to give in return,” said Nia.

“You told me about the hairless people. You gave me good advice.”

Nia made the gesture that meant “it was nothing.”

“It is enough,” said Angai.

Hua held out a pair of saddlebags. “This is for you. I’ve put in everything you ought to have. My mother—the friend of the shamaness—cannot go out onto the plain with nothing.”

Nia took the bags and fastened them to her animal. There was a peculiar feeling in her chest.

Anasu twisted around and unfastened the cloak that lay behind his saddle. “This is for you also. A parting gift, though I have never heard of a boy giving one to his mother.”

“The gift the boy gives is his life on the plain,” said Angai. “He watches the herd. He guides it and guards it. That is enough. That balances the gifts his kinfolk give.”

A true shamaness! thought Nia. She always had an answer. She was always ready to teach and explain.

She took the cloak. It was made of gray wool tufted on one side, so that it seemed like the pelt of an animal. Two brooches were fastened to it, large and made of silver. One was in the shape of a bowhorn lying down, its legs folded. The other was in the shape of a killer of the plain. A silver chain went between the brooches.

Anasu said, “It’s a good cloak. You won’t have to worry about rain as long as you have it. And you won’t be cold even in the winter.”

She fastened the cloak on top of the saddlebags, then mounted and looked at the three of them: the boy on his bowhorn, Angai and Hua standing in the middle of a patch of vegetation. Her hand felt numb. She could not move it. There were no words in her throat or mind.

“Always the same!” her friend told her. “There are things that you have never been able to say.”

“I have never liked the moment of parting.” She made the gesture of gratitude and the gesture of farewell, then turned her animal and rode away.

The entire village was in motion now, heading west. She guided her animal among the wagons, going in the opposite direction. The air was full of dust. Women shouted. Children yelled. Bowhorns made the grunting noise that meant they were working hard and not liking it.

“Huh-nuh! Huh-nuh!

Why are we doing this?

We ought to be running

free on the plain.”

She reached the end of the village. There was nothing ahead except the rutted trail and the droppings of bowhorns. The droppings were fresh and shiny black. She reined White Spot for a moment. There was something else that she had not told Angai. When the parting was over, when the people were gone, she began—always—to feel happy. Aiya! To be traveling! Aiya! To be alone!

She was not sitting properly. Her back was curved, and her shoulder went down as if she carried a heavy load. Nia straightened herself and pushed her chest out. That was better. Now her lungs had room.

A voice said, “I have something to tell you, and I didn’t want Angai to hear.”

She looked back. It was Anasu. His animal breathed heavily through its open mouth.

She made the gesture of inquiry.

“I am planning to visit the hairless people—this winter, before I go through the change.”

“Why?”

“Nothing like this has ever happened. There are no hairless people in any of the old stories and no boats like the one I rode on and certainly no men who live with women. This is utterly new. I want to see it, Nia! I want to understand.

“If I wait—who knows what will happen? Maybe I will turn into one of those men who can endure no one, not even women in the time for mating. Maybe I’ll go crazy.”

“That doesn’t happen in our family,” Nia said.

Anasu made the gesture of uncertainty. “And if everything goes well, if the change is perfectly ordinary, I will end up in the south. I’ve heard about that place! No women get down there. No one brings any information. The big men get everything, and the young men sit and wonder—what is going on in the rest of the world?”

Nia grunted and looked at her son. In the sunlight his dark fur gleamed, and there was—she could see now—a little red in it. Like copper, like his uncle Anasu.

“Be careful,” she told him.

“Of course. I’m not a fool. I’ll do nothing to get myself in trouble. I don’t intend to end up like Enshi or like you.”

“Be polite as well.”

The boy made the gesture of assent. “If you come to the village of the hairless people—in the winter, not before—I’ll be there.”

“Most likely I will come,” she said.

He made the gesture of satisfaction and the gesture of farewell and turned his animal away.

She rode north all day, following the trail of the village. In evening she made camp by a stream. A trickle of water ran down the middle of a wide sandy bed. It was enough. Nia watered her animal and then gathered wood from the bushes along the stream. She made a fire. There was food in the saddlebags: dried fruit and hard, dry travel-bread.

Hu! It was comfortable to sit and watch the flames dance red and yellow. White Spot was nearby. Nia heard the crunching of vegetation and the gurgle of the fluid in the bowhorn’s stomach.

Out on the plain a tulpacried, “Oop-oop. Oop-oop.”

Nia listened for a while, then went to sleep.

She followed the trail of the village for two more days. On the morning of the third day she came to another trail, this one narrow and deep. Travelers had made it. They never used wagons. Instead they led strings of bowhorns loaded down with fine gifts from the Amber People and the People of Fur and Tin. Nia turned east, following the new trail. She traveled for another day. The weather stayed the same: hot and bright and clear. Hu! It was boring! She made up poems. She wondered what had happened to the oracle and Li-sa and Deragu. Were they back in their village? What about her children? Would they be all right? Would they be happy?

Angai had done a good job raising them. Why hadn’t she praised her friend? Why hadn’t she told Hua and Anasu, “You are good children”?

Toward evening there was a noise like thunder: loud and sharp. White Spot broke into a run.

Nia pulled on the reins. The animal did not stop. Instead it plunged off the trail into the vegetation. Nia kept pulling. The animal ran until they came to a stand of blade-leaf. It rose over both of them. The animal reared, then came down on all fours, shaking and snorting and sweating like one of the hairless people.

“This is no way to act,” said Nia. “Be safe! Be happy! There is nothing to harm you.” Nia stroked the animal’s neck, then looked around. The sky was empty. “I’ve heard that before,” she told the bowhorn. “It means that an island has fallen into Long Lake.”

The animal shook its head, snorting again. Nia turned it back toward the trail.

At twilight she came to the river valley. She made camp on top of a bluff, and in the morning she rode down through a narrow ravine. Vines covered the walls, their leaves as red as copper. The air smelled of dust and dry vegetation.

At the bottom of the ravine the land was flat and covered with forest. She continued east. The trail was dry, but she could see that a lot of it would be underwater in the spring. Logs had been laid down in the low places and dirt piled over the logs, so the trail was raised. Aiya! What a construction! She had never seen anything like it before. Who had done it? Tanajin? Or some of the travelers? It was a good gift. Many people would praise it.

In the middle of the afternoon she came to the river. Brown water ran through a narrow channel. On the other side of the channel was an island. There was a raft pulled up on the shore of the island between the river and the trees.

Nia dismounted. The ground around her was covered with ashes and pieces of burnt wood. There were footprints in the dirt—people and bowhorns—and heaps of dung. All the dung was old.

She took care of her animal, then gathered wood and built a fire. Dead wood first. Not the rotten pieces that bugs had eaten. Good dry pieces, solid, with nothing on them except patches of the red scale plant. When the fire was burning really well, Nia added living wood. That made smoke. It rose up like the trunk of a tree, thick and dark.

Nothing happened for the rest of the day. She kept the fire burning. At night she slept close to it and woke several times to add wood. Anything could be in the forest: lizards as big as the umazi,killers with sharp claws, osupaior tulpai.The plain was better. She liked to see what was coming after her.

In the morning she gathered more wood. Her food was almost gone. She got the fire burning well, then sat down and waited. Her body was stiff. Her mind felt like an iron pot: heavy and empty.

In the middle of the day a person emerged from the forest on the island. She pushed the raft into the water and climbed onto it. A forked stick was fastened to the side of the raft. The person fitted a long paddle into the fork of the stick.

The raft drifted out into the river. The person began to move in a way that Nia did not understand at first: bending and straightening. The paddle rose and fell. Water dripped from the wide long blade.

Up and down. In and out of the water. After a while Nia could see what was happening. The paddle was driving the raft. Instead of going downstream with the current, it went across.

Slow work! And hard! Nia watched, feeling restless. It was never easy to sit with empty hands when other people were doing something useful. She got up and moved to the edge of the water.

The raft was close. The person on it was Tanajin. She glanced at Nia, but made no gesture of recognition. Instead she kept the paddle in motion. In spite of all her effort, the raft was drifting downstream. It would come to shore below Nia.

She walked along the bank, then took off her sandals and waded in. “What can I do?” she called.

Tanajin bent and grabbed something. “Here!” She tossed it.

A rope. It unwound in midair and fell into the water. Nia grabbed one end. The other end was fastened to the raft.

“Pull!” said Tanajin.

She wound the rope around her forearm till the slack was gone, then spread her feet and dug her toes into the muddy bottom, got a good grip on the rope and pulled.

Hunh!

The raft slowed.

Hunh!

The raft stopped.

Hunh!

The raft began to turn.

Tanajin swung the paddle out of the water. It stayed up, held by the forked stick, though Nia couldn’t tell exactly how. Then she jumped in the river. Aiya! The splash! She was chest-deep in water, leaning against the raft and pushing hard. Nia kept pulling. The two of them grunted like bowhorns. The raft came to shore.

They climbed out of the water. Tanajin took the rope and fastened it around a tree. “Where is Ulzai?” she asked. “He didn’t come back.”

Nia made the gesture that meant “I don’t know.”

Tanajin made the gesture of inquiry.

“A lizard followed us into the rapids. Ulzai stood up to confront it. Something happened. I don’t know what exactly. The boat went over. We all…” She closed her hand into a fist, then opened it. The gesture meant “scattered” or “gone.”

“Ai!” said Tanajin.

“The lizard was not an umazi.Ulzai got a good look at the animal. He said it was nothing out of the ordinary. He told us about his dream. The umazipromised him they would be his death.”

“What about the hairless people?” asked Tanajin. “And the crazy man? Did they drown?”

Nia made the gesture that meant “no.” “There is a new village on the lake. Hairless people built it, and it looks like no other village I have ever seen. Li-sa and Deragu are there. So is the oracle. I came to fix your pot.”

Tanajin made the gesture that meant “let’s get on with it.”

They walked to Nia’s camp. The fire was almost out. Tanajin kicked the branches apart. Was she crazy? Her feet were bare. She certainly looked angry. She was frowning, and the fur on her brow ridges came so far down that her eyes were hidden.

Nia saddled White Spot, moving carefully and making as little noise as possible. She led the animal to the raft and on. It wasn’t easy. The animal shivered and snorted. “This is no way for a gelding to behave,” said Nia. “Be calm! Don’t act like a male!” The animal flicked its ears. Its tail quivered, but did not lift. That was a good sign. The animal was uneasy, but not really afraid. Not ready to show white and flee. Nia kept hold of the bridle and made soothing noises.

Tanajin untied the rope. She pushed off, using the paddle.

The raft moved gently. It was made of logs tied together. The rope wasn’t the kind made on the plain, woven out of long narrow pieces of leather. This rope was made of a hairy fiber. Nia had seen its like in the east. The Copper People used it for making nets. It came from the distant south.

How many kinds of people were there? How many kinds of gifts?

They drifted toward the middle of the river. White Spot snorted and stamped a foot. Nia rubbed the furry neck. She looked back. There was a lizard in the river between them and the western shore. A big one, heading south.

Aiya! Nia tugged at the bridle, turning the head of the bowhorn, making certain that White Spot couldn’t see. “Have there been many of those?” she asked.

Tanajin glanced up. “Lizards? Yes.”

She went back to paddling. When they reached the island, she spoke again. “I see the lizards when I bring people across the river. They like to travel along this side. The water moves slowly, and there are marshes where they can hunt. The lizard that went after you was behaving very strangely.”

“It was following blood,” said Nia. “The oracle had an injury. He was bleeding into the water.”

“He is the cause!”

Nia made the gesture of disagreement. “I think it goes further back. I think it was the spirits in the cave.”

Tanajin made the gesture of inquiry.

Nia told her about the cave with pictures on the walls. “It was full of spirits, the oracle said. They were hungry. He fed them. But they were not satisfied. They wanted more blood. This is my opinion, anyway. I don’t know for certain.”

“It’s too complicated for me,” said Tanajin. “I need a shamaness. Maybe I ought to go and find one.”

They pulled the raft out of the water and left it there, crossing the island on foot. Noisy birds filled the trees. The ground was covered with droppings: red and purple and white.

On the far side of the island was another raft. They used it to cross another channel.

The same thing happened. They pulled the raft onto the shore. They crossed the island. They found another raft.

“How much of this is there going to be?” asked Nia.

Tanajin made the gesture of ending or completion. “This is the last channel. There is no good way around the islands and if I try to cross the river all at once, the raft drifts too far down. I know. I have tried it.”

Nia said, “The hairless people have a boat that moves by itself as if it had legs or fins.”

“Is it magic?”

“No. It is driven by fire, though I don’t understand how.”

Tanajin made the gesture of amazement. But she didn’t look amazed. Instead she looked tired.

They crossed the last channel. By this time the sun was gone, but the sky was still full of light. The air was almost motionless. It smelled of the river and of the bowhorn, which had dropped a heap of dung on the logs near Tanajin.

“Mind your animal,” the woman said.

“I’m doing my best.”

They reached the shore and pulled up the raft. The sky darkened. They walked north along the river till they came to Tanajin’s house.

Nia took White Spot around back. She unsaddled the gelding and tied it, using a leather rope. The other two bowhorns were there, grazing on the short vegetation. She went around front. Tanajin had built a fire.

They ate without speaking. When they were done Tanajin went into her tent. She brought out a blanket. “I don’t want you in my house, Nia. I am angry at the news you’ve brought. Why is Ulzai the only person who hasn’t reappeared?”

Nia made the gesture of uncertainty.

Tanajin went inside.

Nia lay down. Bugs hummed around her. They bit her in the places where her fur was thin: at the edges of her hands, on the tops of her ears. She pulled the blanket up till it covered all of her and dreamed of being trapped in a dark place: a cave or a forest. There were people around her, moving and speaking. She couldn’t see them and their language was not one she knew.

She woke at dawn. Tanajin came out and rebuilt the fire. They ate porridge.

Tanajin said, “I dreamed about Ulzai. His clothes were soaked. Water dripped off his fur. He spoke to me. I could not understand his words.”

“I dreamed also,” said Nia.

“About what?”

“Darkness. Being trapped. And people. I don’t know which people. They spoke. I could not understand them.”

“These are bad dreams. We need a ceremony of aversion.” Tanajin frowned. “There are times I think this is no way to live. I have no female relatives. I have no shamaness. Now even Ulzai is gone.”

Nia made the gesture of polite agreement. “You said you have tools. I am going to begin setting up a place to work.”

Tanajin made the gesture of acknowledgment.

She built a forge downriver from the tent. It took nine days of hard work. The weather stayed the same. There were bugs every night. Tanajin gathered living wood and put it on the fire. The smoke drove away most of the bugs. Nia was too exhausted to mind the ones that remained.

Every morning she was stiff, but the stiffness wore off. The real problem was her hands. Blisters formed on the palms where the calluses had gotten thin. The blisters broke. The flesh beneath was red and tender. She wrapped pieces of fabric between her fingers and over the palms. Aiya! How clumsy that made her! She kept working.

“You don’t have to hurry,” said Tanajin.

“I like it. I understand what I am doing. It has been a long time since I’ve been able to say that.” She paused, trying to think of a way to explain. “This is the thing I do. This is my gift.”

Tanajin made the gesture of dubious comprehension.

The day that the forge was completed, something odd happened. A cloud appeared. No. A trail of smoke. It rose out of the south, going diagonally west, forming with amazing rapidity. Not like any smoke that Nia had ever seen. Up and up it went. Nia shaded her eyes. Was there something at the tip of the cloud? Something leaving the trail of smoke? That was hardly likely.

She listened. There was no sound of thunder and nothing in the sky except the trail, which had risen so high that she could no longer see the end of it.

“Huh!” She went back to work.

In the evening she went back to the house of Tanajin. The woman sat by her fire, cooking fish stew in a pot that hung from a tripod.

“What was that about?” she asked Nia.

“The cloud? I’m not certain. But the hairless people are south of here.” Nia scratched her nose. “I wonder how many islands there are in the lake. I wish I had a talking box. I’d ask the oracle or Li-sa.”

Tanajin made the gesture of inquiry.

Nia told her about the islands that fell out of the sky. “They come down with noise. Maybe they go up with smoke.”

Tanajin made the gesture of doubt. “Many things fall out of the sky. Rain of different colors, snow, hail, pieces of iron and stone. I’ve never heard of anything going back up again. Only smoke rises.”

Nia made the gesture that meant “you aren’t thinking about what you are saying.” “When the fire demons are active, the mountains throw up stones, and they can travel long distances. Ash rises at the same time, and fire.”

“You think these people are a kind of demon?”

“No. I think they have tools that are nothing like our tools, and strange things happen around them.”

Tanajin made the gesture of courteous doubt. “I am willing to believe that mountains cough up stones, though I have never seen one do it. I am not willing to believe that a lake can spit islands into the sky.”

The next day Nia began to repair the tools that belonged to Tanajin. Travelers came from the east: eight women who belonged to the People of Fur and Tin.

Tanajin ferried them across the river. It took her two days. When she got back, she said, “They have come from visiting the Amber People. A bad visit! Everyone there is quarreling. A ceremony has been ruined. They have been accusing one another.”

Nia shivered and made the gesture to avert bad consequences.

Tanajin went on. “They saw the cloud in the south. I told them about the hairless people. I said I knew the people existed. I had seen them. But I hadn’t seen any islands fall out of the sky. That news came from Nia the Smith, I told them.”

“You told them my name?”

Tanajin made the gesture that meant “don’t worry.” “I said you came from the east. They do not realize you are the woman who loved a man.”

“That’s good,” said Nia.

She continued to work on Tanajin’s belongings. The weather continued bright and hot. Late summer weather. The ground was dry, even close to the river. On the plain everything would be covered with dust. The village—traveling—would send up great dark clouds.

At night many arrows flashed out of the pattern of stars called the Great Wagon. That was ordinary. Those arrows came at the end of every summer. The Little Boys Who Never Grow Up were riding in their mother’s wagon, shooting their bows. Aiya! When she caught them!

Nia finished with Tanajin’s pots and began on her own gear: bridle bits, the rings on saddles, knives that needed sharpening, awls that would not punch through anything. Tanajin had a coil of iron wire. Nia made needles.

Now and then she saw clouds of the new kind: long and narrow. Usually they were in the south or southwest. They formed rapidly like the first cloud, and they were the same shape, but they didn’t rise to the peak of the sky. Instead they were horizontal. It was easiest to see them in the evening. The sun lit them from below. They shone like colored banners: red, yellow, purple, orange, pink. Sometimes Nia thought she could make out the glint of metal. The thing that glinted was always at the front end of the cloud, at the place where the cloud began.

She worked and thought. After a while she got an idea. It seemed crazy to her. There was only one thing to do with a crazy idea. Tell it. Only men kept quiet when something was bothering them. Or women who were doing or thinking something that was shameful.

Nia spoke to Tanajin.

“The clouds are in the south, where the hairless people are. They are new, and the clouds are new. Therefore they are responsible.”

“Maybe.”

“I told you about their boats. The boats leave a trail in the water. The trail is white. It forms rapidly and then vanishes. Maybe the clouds are trails as well.”

“In the sky?” said Tanajin. “Don’t be ridiculous. First you said these people are able to fling stones around like demons. Now you say they can float in the sky like spirits. How likely is any of this?”

Nia made the gesture of concession. “Not very.”

“You have spent too much time alone, Nia. You are getting crazy ideas.”

Nia made the gesture that meant “yes.”

Travelers came from the west and built a signal fire. Tanajin went to get them: five large morose women. Their tunics had brightly colored vertical stripes. Their saddlebags were different from anything Nia had ever seen before: large baskets made of some kind of plant fiber and striped horizontally.