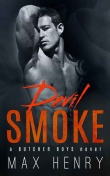

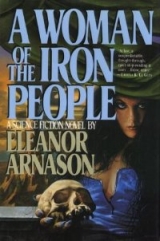

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

“Yes?” said Derek.

“I do not want to ask you.” Ulzai looked at Nia. “Tanajin told me that you are a smith.”

Nia hesitated, then made the gesture of affirmation.

“She said that you belong to the Iron People.”

“Yes.” She paused. “I used to.”

“Are you the woman we heard about?”

Nia said nothing.

“She was a smith, and she belonged to the Iron People. I don’t remember her name. I am not certain that Tanajin ever told me. But she did tell me the story.”

“What story?” asked Nia.

“The woman who loved a man. The Iron People tell it. So do the Amber People and the People of Fur and Tin. She is a famous woman! Are you the one?”

“Do you mean to cause trouble?” Nia asked.

“No. Why do you think I agreed to help you? Tanajin is the ferry woman. I am not.” He paused for a moment. “Do you think it is easy for me to spend three days with other people? There are so many of you! And those two are peculiar.” He glanced at me and Derek.

Nia made a barking noise. “There is a woman to the east of here. She thought she knew me. She tried to kill us.”

“When Tanajin first heard your story, she said to me, ‘We are not alone. We are not the first people to have done this thing.’ ” Ulzai frowned. “I do not entirely agree with her. In the story they tell about you, you chose to treat a man like a sister or a female cousin. It was not an accident. You deliberately set out to do something offensive.”

By this time the cave was dark, except for the light cast by the fire. It flickered on the walls. The eyes of the people around me gleamed: red, orange, yellow, and—most startling—blue. Thunder rumbled outside. Rain fell.

Nia said, “I will not argue with a story that has been told over and over. Let people believe what they want to believe.”

“It was different with us,” said Ulzai. He looked around. “I brought a jar of beer.”

Derek found it and handed it over. Ulzai drank. “I have never told the story to anyone. I do not want to be famous on the plain.”

Nia barked again. Ulzai gave the jar to her. She drank.

He hunched forward, staring at her, ignoring the rest of us. “It is not true that men like to be silent. We learn to be silent. Who is there to talk to in the marshes? The spirits. The lizards. The dead folk who wander at night. It is possible to see them. They are dim lights over the pools. They never speak. Neither do the spirits. Or if they do—” He glanced at the oracle. “I cannot hear them. I am not holy.”

“I am,” the oracle said.

“Tanajin told me.” He looked at the fire. After a moment he rubbed the side of his face, running his hand along the lines of white fur. “I have kept the story in me for winter after winter. It is like a stone in my belly. It is like a bad taste in my mouth. It aches like an old wound in the time of rains. I do not understand it. I do not see what else we could have done.”

Nia sighed. “Tell it then. I warn you. It will not help. Words are less use than you think.”

“Maybe,” said Ulzai.

The oracle said, “Can I have some beer?”

“What about your stomach?” asked Derek.

“Beer is good for the digestion.”

Nia gave him the jar.

Ulzai scratched his head. “It’s a long story.”

“We have time,” said Derek. “That storm isn’t going to end soon.”

“You two.” He glared at Derek and me. “Keep quiet about what you hear. And you as well, o holy man.”

We made the gesture of agreement, all three of us.

“First of all, I have to tell you about the People of Leather. I used to belong to them. So did Tanajin. They live in the marshes where the Great River goes into the plain of salt water. Their houses are not like any I have seen in other places. The marshland is flat and when the river rises, the land is flooded. All of it. The people build their houses on top of frames made of wood. I do not know how to describe these frames. They look something like the frames that people use to dry fabric or fish. But they are much bigger and solider. On top of each frame is a platform. On top of the platform is a house. The walls are made of reeds and branches woven together. The roof is made of bundles of reeds. The bundles are thick. Not even the heaviest rain can get through.” He paused for a moment, his eyes half-closed, remembering. “There are no trees in the marsh, only reeds—though they can grow taller than a man. The houses rise above the reeds. They are taller than everything. A man can look up and see them, even at a distance. At night he can see the cooking fires on the platforms.”

Derek leaned forward. “If there are no trees, where do you get wood for the houses?”

“The river brings it. When the river gets to the marshes, it spreads out. The water moves slowly then. The river drops whatever it has been carrying. There are sandbars at the entrance to the marshes and a great raft of wood. The raft fills most of the river, and it is so long that a man can paddle for days, going upstream, and never see the end of all that wood. There are more trees than anyone can count tangled together. Most are worn by the water. They have lost their bark. They are as gray as sand. They are as white as bone. But they are not rotten. They can be used.”

“Aiya!” said the oracle.

Ulzai frowned at the fire. “Now I have forgotten what I was going to say.”

“You were talking about your people,” I said.

He made the gesture of agreement. “The women live in the houses, high above the reeds. The men live in boats. That is what every boy gets when it is time for him to leave the house of his mother: a boat with a carved prow and a set of spears, a knife for skinning and a cloak of lizard skin. Those four gifts are always the same.

“The boy gets them. He says farewell to his mother and to his other relatives. He paddles away. He does not return until he has killed a lizard. A big one. An umazi.”

“What do you mean when you say, he returns?” asked Nia.

“I know the people here on the plain would not approve of our behavior. Our gift is leather. The men hunt the umaziand cut off their skins.

“But the skin is good for nothing, unless it is tanned, and the women do the tanning. They are the ones who have the big vats made of wood and iron. They are the ones who have the urine. Where could a man possibly get enough urine to fill a tanning vat? And where would he keep the vat? Not in his canoe and not on the islands, which are often covered with water.

“When a man kills an umazi,he brings the skin to his mother or to a sister if his mother is dead.”

“I have never heard of such a thing,” said the oracle.

“It is done decently. The man waits till the big moon is full. Then—at night—he goes to the house of his mother. He ties up his boat. He climbs onto the platform. She is inside. The windows are covered. The door is fastened. She makes no noise at all.

“He lays down his gift. The raw umaziskin. He gathers up the gifts she has left for him outside the door. He goes. Nothing is said. They do not see each other.

“This must be done. Otherwise we have no leather, and we are the People of Leather.”

“Hu!” said Nia.

“This is what you did?” asked the oracle.

Ulzai made the gesture of affirmation. “Until my mother died. My sisters were dead already. I had no female cousins. That is how it began.”

“How what began?” asked Derek.

“I am a good hunter. No man killed more umazithan I did. My mother had more skins than she could handle. She gave away half of what I brought her.

“Sometimes at night I’d bring my boat in to the home channel. I’d drift below the houses in the darkness. I’d hear the women singing. They would praise my skill and her generosity. You have to understand, it was good to listen.”

“You should not have been there,” said Nia.

“I like praise,” said Ulzai. “She died. I had no close relatives in the village. There was no one to bring my skins to. They were useless to me. All my skill as a hunter was useless.”

“Aiya!” said Derek.

“Get more wood,” said Ulzai.

Derek obeyed. Ulzai put two branches on the fire and watched until they caught. I listened. The rain was still falling.

He lifted his head. “Sometimes, when a thing like this happens, the man—the hunter—gives up hunting. He goes deep into the marsh and lives by fishing. He becomes ragged. He forgets how to speak. I have seen men like that at the time of mating. They try to force their way back into the area close to the village. I have faced two or three. They do not shout insults like ordinary men. They growl and make grunting noises. They draw their lips back and show their teeth. One raised his spear, as if he planned to use it against me. In the end he did not. He made a strange noise—something like a groan—and ran away.” Ulzai added branches to the fire.

“Other men look for another woman. Maybe there is a distant cousin who has no brothers. Maybe there is an old woman who has outlived all her relatives.

“But it is not easy to come to an agreement. The two people cannot speak. They cannot look at one another. The woman does not know who visits her, leaving the lizard skins. She has no idea of the right gifts to give him. A mother would know. So would a sister.

“Often the woman is afraid. The people in the village gossip when a woman who has no relations sets up a tanning vat. They ask questions. They have ideas. It is never good to attract the interest of your neighbors.”

“That is true,” said Nia.

“I was not willing to give up hunting. I didn’t want to become a crazy man. I came into the village on dark nights. I stopped my boat under houses. I listened to the women talking. No one heard me. No one saw me. I am good at what I do.

“I learned that something had happened to the brothers of Tanajin. They had stopped coming to her house. She had nothing to tan. I decided to visit her.” Ulzai got up and lifted the vines at the entrance to the cave. Water dripped off the leaves. I looked out and saw rain.

“I am getting tired of telling this story. It goes on and on. Maybe silence is better.”

“Stop if you want,” said Nia.

I kept my mouth shut, though I wanted to hear the rest of the story. Derek frowned.

“I will finish,” Ulzai said. He sat down. “I left a skin. The next time the moon was full, I came again. She had put gifts outside her door. Food and a jar of beer and a knife. The hilt was black wood inlaid with silver. It wasn’t the right size for my hand.”

I made the gesture that indicated sympathy or regret.

“After that I came at every full moon. I brought her many skins. They were large and in good condition. She gave many away. But I did not hear the women sing in praise of her. And I did not always like the gifts she gave me.

“She gave me sandals made of lizard skin. They were too small. She gave me fabric for a kilt. It was dark green, covered with red and yellow embroidery. Most men would have liked it. But I like things that are plain.”

“Why?” asked the oracle.

“It’s the way I am.” He paused. “There is nothing handsome about me. There never has been. I got this when I was a child.” He touched the white fur on his face. “I fell off the platform of my mother’s house. A lizard got me. There are usually a few under the houses in the village. They are never big. The umazido not live on garbage. But at the time the lizard seemed big enough to me. I shouted when it bit me. My mother dove in with a knife. She killed the lizard—and I was left with this.” He touched his face a second time. “And this.” He touched the white fur on his leg.

Nia said, “That must have been an experience.”

Ulzai made the gesture of agreement. “Give me the beer.”

I handed him the jar. He drank. “I decided to talk with Tanajin. But not in the village. I was afraid the old women would find out. I heard them talking on top of their platforms. They were like mothers hunting for vermin in the hair of their children. They hunted for bad ideas. They wanted to know something bad about Tanajin. I did not know why.

“I waited until the time of mating. I hid in the reeds near her house. When she left to go into the marshes, I went after her.

“I found her, but I wasn’t the first one. There was a man with her. I confronted him. He became angry. We fought. I beat him, though it wasn’t easy. He ran off into the marshes, and I spoke to Tanajin. I showed her the size of my feet and hands. I told her what kind of cloth I liked. I told her I always used the kind of spear that has a barbed head.”

“Did you mate with her?” asked Derek.

Ulzai made the gesture of affirmation. “But nothing came of the mating. She had no child. That was the first mistake I made.”

“What?” asked Derek. “The mating?”

Ulzai frowned. “No. Following her. Talking with her. Before that, she had been nothing. A shadow in the shadows of the house. Now she became something. A person. I knew what she looked like. I knew the sound of her voice. At times, when I was in the marsh or sitting on the platform in front of her house, I thought of her. I opened my mouth. I thought of speaking. Then I bit my tongue.” He stood up again. “The rain is stopping. I am going out.” He pushed through the vines.

“Interesting,” said Derek in English. “How hard it is to maintain the barriers between people.”

“You think so?” I said.

“Maybe I mean the opposite. Ulzai is right. It’s time for a walk.”

He left. I looked at Nia. Her dark face was expressionless.

“The world is full of strange people,” said the oracle. “And stories which I never expected to hear. Maybe that is why my spirit told me to travel. I am going to drink more beer.”

I decided to go out.

Ulzai was right about the rain. It had stopped. In the west, beyond the river, the clouds were beginning to break apart. I glanced around. Derek and Ulzai were out of sight. I walked along the cliff until I found a place where I could climb. Up I went until I was high enough to see across the valley.

Winding channels. Islands. Marsh. The forest on the far side of the river. Rays of sunlight slanted between the clouds. Where they touched the forest, it was bright green or yellow.

The wind was cool and smelled of wet vegetation. I sat down and leaned against a rock. A flock of birds wheeled over the river. There must have been two or three hundred of them. They were too far away to be visible as anything except dots. I wondered what they were doing. Getting ready to fly south? I had seen birds do that on Earth. They flocked together and flew around, practicing migrating. Then one day—in October or November—one noticed that they were gone.

Well, hell, it couldn’t be easy—flying south. I could understand why they had to practice. The birds in front of me flew off. I sat a while longer, then went back down the cliff.

Derek came up from the river. He carried a fishing rod and a string of fish. They were small, at least in comparison to the fish he’d caught the day before, with round, fat bodies and bright yellow bellies.

“I hope they’re edible,” he said.

We returned to the cave, and Derek held up the string. “How are these?”

“Delicious,” said Nia. “But they are not easy to clean. I will do it. You might ruin them.”

“Be my visitor,” said Derek.

Nia frowned. “What does that mean?”

“Go ahead.”

She cleaned the fish, and we roasted them. Ulzai came back. When he lifted the vines, sunlight came in. The sky in back of him was clear and bright.

“Are you going to finish your story?” asked Derek.

“Yes.” He let the vines drop. We were back in shadow. “But first I will eat. Did you catch these?”

Derek made the gesture of affirmation.

“Your pole is good for something.”

Derek made the gesture of gratitude.

Ulzai ate and drank the rest of the beer. He belched. “There isn’t much left to the story. I brought more skins to Tanajin. The gifts she gave me were better than before. I hunted for her all summer. She gave away many skins. But the women did not praise her generosity. Or if they did, it was grudgingly. I heard them. They said, ‘What right did she have to be prosperous, a woman with no relatives?’

“Winter came. It was warmer than usual. Few lizards came down the river from the north. The umaziwere hungry. The hunger made them irritable, and they were more willing to fight. Men died, and other men gave up. They hunted fish instead of the umazi.I kept on. I brought my skins into the village when the moon was full. I never failed.” He lifted his head. I could see his pride.

“Tanajin was generous. I have said that before. She continued to give away skins. At night, when the moon was dark, I came into the village to listen.”

Nia frowned. “I still say that was wrong.”

“Have you done nothing worse, o woman of the Iron People?”

“I have done much that is worse.” Nia’s voice was even.

“I heard the women of the village. They sat in front of their houses and spoke together. They did not praise Tanajin. They said, ‘Who is helping her, this woman without brothers? Who brings her fine skins when the rest of us get nothing?’

“They said, ‘Even Ulzai was not able to kill this many umazi.And he was the best of the hunters. Tanajin has gotten help that is out of the ordinary. Maybe a spirit takes the luck from our sons and our brothers.’

“I wanted to shout up at them, ‘You fools, I am the one who is helping Tanajin. Ulzai the hunter! I am no spirit!’ But I could say nothing.”

Nia made the gesture of agreement. “That is what happens when you listen in secret. You hear things you don’t want to hear. You have to bite your tongue.”

Ulzai looked angry. “Don’t criticize me.”

For a moment or two Nia was motionless. Then she made the gesture of agreement, followed by the gesture of apology.

Ulzai made the gesture of acknowledgment. “I left and came again. I heard more malicious gossip. They said it was dangerous to go near the house of Tanajin at night. A giant umazilay in the dark water under the platform. A white bird sat on the rooftop.”

“Aiya,” said the oracle.

“I heard a boy speaking. He wasn’t very old. I could tell that from the sound of his voice. He said he looked down from the house of his mother on a night when the moon was full. There was a man in the home channel, standing in a boat and poling it toward the house of Tanajin. The boat was full of the skins of lizards. The man looked up, the boy said. His eyes shone like sparks of fire. He opened his mouth. The mouth was empty. The man had no tongue. It was Ulzai, the boy said. It was me, and I was dead. Tanajin had worked magic and pulled me from the place where I lay in the cold water of the marsh. Now I worked for her.

“He was lying,” said Ulzai. “I wanted to call him a liar. ‘I am Ulzai,’ I wanted to yell. ‘I am alive and I use a paddle, not a pole.’ ”

“Hu!” said Derek.

“I do not know why any of this happened. Why did they praise my mother? Why did they say bad things about Tanajin? Do you know?” he asked Nia.

“No.”

“I was angry. I decided I would kill no more umazi.I went into the distant marshes and lived on fish. The weather grew cold. Rain fell. I got the shivering sickness. I’d had it before. Most men get it after they have lived in the marsh for a while.” He paused. “This time it was bad. First I became too sick to fish. Then I became too sick to eat. I lay in my boat under my cloak of well-tanned umaziskin. Rain fell. I shivered and dreamed.

“The great lizards came, swimming out of the marshes. They formed a circle around me. They spoke. ‘Why have you given up on us? Is there anything more splendid than an umazi?Look at our sharp teeth! Look at our claws! We are huge and frightening. Will you ever find a prey more worthwhile?’

“I tried to answer. My teeth chattered, and I could not speak.

“ ‘You have become a coward, Ulzai. You use your spear on little fish. You fear the voices of women. You lie here and wait to die of the shivering sickness.

“ ‘We are your death. Not this miserable illness. We will get you one day, but only if you hunt us. Get up now! Paddle to the village. Go to Tanajin. She will help you. And when you are well, come after us.’

“They swam away, and I got up. I could hardly sit. The world moved in a circle around me, and I wanted to lie down, but I could not. The umazihad told me what to do.

“I paddled to the village. I came during the day, though I did not realize it. The world seemed dark to me. I reached the house of Tanajin. I tied my boat, but I could not climb up.

“She came down. I told her the lizards had said I must come to her. They were my death. I could not die of anything else. They had told me so.

“She helped me climb the ladder. She helped me into the house and made a bed for me—there, within the walls of her house. She cared for me until I was over the sickness.

“That is the end of the story. We could not stay in the village. They knew now—the old women—who had helped Tanajin. Ulzai the hunter! There was no magic. No bad spirit.” He spread his hands. “Only Ulzai. Ulzai who would not die. Who came into the village.

“Now they were angry because of that. I should have died in the marshes. Tanajin should have left me in the boat.”

He reached for the jar that had held the beer.

“It’s empty,” Derek said.

Ulzai made the gesture of regret. “Tanajin packed up. We loaded my boat. We left together.”

“Why?” asked Nia.

“Tanajin needed help. She didn’t know anything about living outside the village. And I was angry. I no longer cared about the opinions of other people. I had tried everything I could to win the praise of those women. I was even willing to die alone in the marshes until the umazitalked to me.

“I decided—from now on I would help those people who helped me. And I would listen to no one.” He paused.

“Tanajin made a poem.

“I am leaving

these marshes.

I am going far away.

“I will never

hear you again,

O women of the village.

“Making noises

like the birds

in the high reeds.”

He made the gesture that meant “so be it” or “it is finished.”

The rest of us were silent.

Ulzai stood up. “I am going out again. Maybe I’ll return tonight. Maybe I won’t.” He left the cave.

Derek shifted position, bringing one knee up and resting his arm on it. His long hair was unfastened at the moment. It fell around his shoulders, and one lock was in his eyes. He brushed it back, then scratched his chin. “The first thing I’m going to do when we get back is get rid of some of this fur.”

“But you have so little!” said Nia.

One of my fingernails was ragged. I gave it a bite. “I don’t understand the story.”

“You don’t have to understand everything,” said Derek.

“Why did the women of the village dislike Tanajin?”

“There are women like that,” said Nia. “They don’t fit in. Maybe they like to quarrel or maybe they hold themselves aloof from other people.

“I had a friend when I was young. Angai. She was the daughter of the shamaness, and she had a sharp tongue. Most people didn’t like her. They talked about her, though not usually when I was around.”

“What happened to her?” I asked. “Did she end up like Tanajin?”

Nia made the gesture that meant “no.” “Her mother died. She became the shamaness. I have told you about her. I am sure of that.”

“I don’t remember. Were you a person like Tanajin?”

“No,” said Nia. “I was ordinary. People didn’t talk about me.” She frowned. “I don’t think they did. Not until they found out about me and Enshi. Then everything changed.”

She looked uncomfortable. I changed the subject. We talked about the weather and then about the river. Ulzai did not return. The fire burnt down, becoming a heap of coals. One thin wisp of smoke still rose from it, curling into the leaves. I lay down, listening to the others. Their voices grew softer and more distant, until finally their words lost meaning.

Derek woke me in the morning. “Come on. Ulzai says it’s going to be a long day.”

I rolled over and groaned. The air felt damp. My arms ached. I went outside to pee.

A fog filled the valley. The river was invisible. The bushes, even the ones right in front of me, were dim and colorless. Not a day for the solar salute. I did some stretching exercises, then went back in the cave. No one had bothered to rebuild the fire. The cave was dark and warm. It smelled of furry bodies. A comforting aroma.

We packed up.

“How can we travel?” asked Nia. “I’ve been outside. The air is like the belly fur on a bowhorn. We are not going to be able to see anything.”

“I know the river,” said Ulzai. “We can travel half a day before we reach anything that is unusual or dangerous. And the fog will be gone by then. The air will be clear by the time we reach the place where the water goes down.”

“Are you certain?” asked the oracle.

“Yes,” said Ulzai. “Come on. And be careful.”

We started down through the fog, Ulzai first. The rock we climbed over was slippery. I could see hardly anything: the dim figure of Ulzai, a few shadowy bushes. I brushed against one. The leaves were edged with drops of moisture. Somewhere close by, the stream made gurgling noises.

“Ai!” someone shouted.

I turned, seeing Nia and Derek. The oracle was gone.

“What happened?”

Nia made the gesture of uncertainty.

“The damn fool went into the ravine,” said Derek.

“Help,” said the oracle. His voice sounded distant, though he had to be close.

Derek peered into the ravine. “I can’t see him. Oracle! Call again!”

“Help,” said the oracle.

“Straight below.” Derek set down the bags he carried, pulled off his boots and socks, and climbed into the ravine.

“What is going on?” asked Ulzai behind me.

“The oracle has fallen into the ravine.”

“A clumsy man!”

I made the gesture of agreement.

“I have him,” said Derek. “Can you stand?”

“I don’t know,” said the oracle.

“Try it.”

There was a moment of silence.

“Aiya! My ankle hurts!”

Ulzai snorted. I walked to the edge of the ravine and looked in. There were shapes below me: rocks and branches, just barely visible through the fog.

“Come on,” said Derek. “I’ll help you climb.”

The branches moved. Two figures appeared: one pale and human, the other dark and solid and alien. I knelt and reached down a hand. The oracle grabbed hold. I pulled. Derek lifted. We got him out.

“How could such a thing happen?” asked the oracle.

“Don’t ask us,” said Derek. He knelt by the oracle, who was sitting down, and felt the little man’s ankle. The oracle moaned.

“I can’t feel anything wrong, and you don’t seem to be in a lot of pain.”

“There you go again,” said the oracle. “You are measuring the pain another person feels. How can you do that? What kind of magic do you have?”

“You aren’t screaming when I do this,” said Derek. He pressed.

The oracle gasped. “I will scream, if that is what you want. Let me breathe deeply first.”

“We are wasting time,” said Ulzai. “If the ankle is broken, the man will find out. The pain will get worse and the ankle will get bigger. If he’s all right, he will find that out, too. Come on!”

Derek helped the oracle up. The little man groaned, but he was able to stand on the injured foot. He hobbled down the slope, leaning on Derek. Nia and I carried the bags.

The fog was lifting a little. I could see the edge of the river. Gray water lapped gently against a beach of gray sand. The center of the river was impenetrable whiteness.

We pushed the boat into the water. The oracle climbed in, settling down and groaning. The rest of us followed: Derek at the prow and Nia in back of him. I ended between the oracle and Ulzai. It wasn’t an especially comfortable place to be. I was very much aware of Ulzai in back of me: huge and hairy and formidable. Something sharp and hard was pressing against my thigh. I shifted and looked. It was the blade of a spear, long and barbed, made of iron. It lay on the bottom of the boat, along with another spear and Derek’s fishing pole. I had come close to sitting on the tip.

The boat moved away from shore.

I shifted back, trying to get away from the spear blade.

“Don’t do that,” said Ulzai. “I need room to paddle.”

I shifted forward.

“Good.”

We traveled through the fog all morning. The air was still, and there was no sound except the splash of the paddles. The silence had an effect on us. We barely spoke, and we moved carefully, trying to make as little noise as possible. The oracle was an exception. He moaned from time to time and shifted position. It seemed to me he was favoring his injured arm.

The fog grew thin. Islands emerged from the whiteness. The current picked up, and the surface of the river changed. There were ripples and eddies.

“We are getting to the place where the river goes down,” said Ulzai. “The fog has lasted longer than I expected. I am trying to decide whether or not I want to go on. The boat is overloaded. There might be problems, and I don’t want to come on them suddenly.”

The oracle moved again, trying to find a comfortable position. His injured arm was resting on the side of the canoe. He lifted it. I saw blood drip into the water.

I leaned forward, grabbing the arm. He twisted. The boat rocked.

“Be still,” I said.

The bandage had torn open. The edge of the foam was red with blood. Blood soaked the fur. A dark line of blood ran down the inside of the canoe. I leaned out. The boat rocked again.

“What are you doing?” asked Ulzai.

A second trail of blood ran down the outside of the canoe into the water.

“Blood,” I said. “Didn’t you say it was dangerous to let blood get into the water?”

“Yes.”

“The oracle is bleeding.”

“Move back,” said Ulzai. “Take my paddle.”

I obeyed. He stood and stepped over me. I tucked myself into the stern. Ulzai picked up a spear. He straightened up, glancing around.

“Nothing yet. But you, o holy man, keep your arm in the boat. I want no more blood in the water.”

The oracle held his arm against his chest. His shoulders were hunched. I had a sense that he was frightened. Well, so was I.

Ulzai spoke again. “They do not like this part of the river. The water moves too quickly. They do not come here except in the time for migration, and that has not begun.”

Derek said, “Good.”

“If there are any around—if a few of them have decided to go south early, ahead of the rush—they’re likely to be close to shore. Or else behind us. Upriver. We’ll keep going. Pay attention to the current. It is strong and getting stronger. Stay with it. There are rocks to the west. Watch out for them and look to the east from time to time. If you see anything dark in the water there, give a shout. It will be a lizard.”