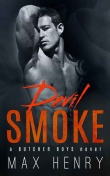

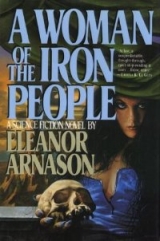

Текст книги "A Woman of the Iron People"

Автор книги: Eleanor Arnason

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

They finished drinking the water. The oracle pulled an ice cube out of his glass. He held it on his palm, looking at it. Then he poked it with a finger. “It is ice.” He popped it into his mouth. I heard a crunch.

“You can do that with the ice,” I said. “But not with the glass.”

The oracle made the gesture that indicated understanding. Derek returned, a woman with him as tall as he was and as black as coal. She wore a bright yellow coverall and a pair of truly amazing earrings. Two huge disks made of hammered metal. When she got closer, I saw her eyes. The irises were silver, the same color as the earrings. There were no pupils.

Contact lenses, of course. It wasn’t an Earth fashion. She was from one of the L-5 colonies or from Luna or Mars.

She had a bag in one hand. After a moment I realized the bag was moving. Something inside it was alive. She looked at Nia and the oracle. “Well, they certainly are alien. There can be no doubt of that.”

Derek said, “According to Marina, they oughtto be able to eat our food.”

“The trouble isn’t that we are poisonous to one another,” the woman said. “The trouble is the members of one system cannot metabolize the food that comes from the other system. If these people eat our food for any length of time, they are going to end up with some really terrible deficiency diseases. But one or two meals should not hurt them.

“However,” she paused. “Having said all that, I do not recommend that we give them our food. Instead—” She reached into the bag and pulled out a fish. It twisted in her hand. “Ask your friends if this is edible.”

I did. Nia made the gesture of affirmation. Marina gave the fish to the blond man. “Broil it. Add nothing. No butter. No salt.”

“All right,” the man said. He went into the kitchen.

Marina sat down. “There are always allergies, and unpredictable reactions of one kind or another. We don’t want to kill the first aliens we have ever met.”

“No,” I said.

“What is going on?” asked Nia.

“The little man is going to cook the fish,” I said. “The woman who just came in says it is possible that our food might harm you.”

“Aiya!” said the oracle. “This is a strange experience.”

Nia made the gesture of agreement.

The black woman introduced herself. Her name was Marina in Sight of Olympus, and she was from Mars. She was a biologist. Her specialty was taxonomy. She had spent years classifying the fossil life of her home planet.

“It got to be depressing. All those wonderful little creatures! As strange as anything we had on Earth during the Precambrian. And all of them were gone. Everything was gone. The planet was dead except for us. You can see why I jumped at the chance to join the expedition.”

Nia looked irritated. “It is hard to be around people who do not understand the language of gifts.”

I made the gesture of agreement. The blond man came back with two plates of broiled fish.

“It was hard,” he said. “I couldn’t even add a garnish.”

Nia and the oracle ate quickly and neatly with their hands. The rest of us tried not to stare at them.

When they were done, Nia said, “I am going into the forest. If I can find the right kind of wood, I’ll make a trap. I have been afraid to go down by the lake, since your people seemed to be everywhere on it. But now I am less afraid. And if I cannot eat your food, I will have to find food for myself.”

I made the gesture of agreement.

“So many new things! How do I get out of this house?”

I led her to the door.

“I will be back at nightfall.” She turned and walked through the camp toward the forest. People watched her. I returned to the dining room.

The oracle said, “I would like to sleep.”

“Okay,” said Derek.

They left. The blond man made a stack of plates and glasses. “They are going to have to learn to pick up after themselves.”

“They aren’t likely to be using the dining room much,” I said.

“Maybe not.” He went into the kitchen.

I looked at Marina who said, “I have to go feed an ugly-nasty.”

“What?”

“I am collecting specimens, and I haven’t started giving them Latin names. This has been an amazing day. See you later.”

She left. I sat a while longer, alone, thinking, they are alive. Then I went outside.

The wind blew south and east, carrying the clouds away. By midafternoon the sky was clear. I located the biology dome. It was pale yellow and full of cages. Most of the cages were occupied. Birds whistled. Bipeds made piping noises. The ugly-nasty grunted and snuffled.

“What is it?” I asked.

“I figure it’s a prince, under some kind of a curse,” Marina said. “Look at those warts! Look at those bristles!”

The creature paced, claws clicking. It was designed for digging and had a long narrow snout. Not like an anteater. This creature had a lot of teeth.

“I can see what’s ugly about it.”

“But what is nasty? It throws up when it gets nervous. I think it’s a defense mechanism. It surely put me off.”

“What is it?”

“That is an interesting question.” Marina seated herself on a corner of a table. Next to her was a cage full of little lizards, striped yellow and bright pink. The lizards scurried up the sides of the cage and hung from the top. “There, there, honeys. I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

The lizards stopped moving. They hung upside-down, frozen. I had the sense they thought they were invisible.

“Remember that cave you found just before you reached the river valley?”

I looked at her surprised. “Yes.”

She grinned. “I’ve seen the reports. There were paintings on the walls. People and bipeds and some mighty big lizards, but no—I’m not certain what to call them—pseudo-mammals. Or mammaloids. No furry critters.

“We think there is a chance that the two continents here have been separated for a long time and have developed really different ecologies.

“There are birds on the big continent. They could have flown there. And a lot of animals that remind us of mammals. But no bipeds.

“This continent is full of birds and bipeds and animals that remind us of lizards. But there are not a lot of animals with fur. Most are small or, if not small, they are domesticated.”

“They came with the people,” I said. “And the people came from the big continent.”

“Right. That’s what we think. But we are working from almost no data.

“We think the paintings that you saw were done after the first people arrived, but before they’d had much of an effect on the local fauna. Maybe the first people came before the domestication of animals. Or maybe they had boats too small to carry much of anything. As I said, we have almost no data.

“Which brings me to the ugly-nasty.” She waved at it.

It snuffled, then yawned, showing rows of pointed teeth. A black tongue curled. What did it eat?

“Raw meat and leaves,” Marina said. “It is an omnivore.”

“Can you read minds?”

“I can make obvious deductions.” She waved again. “It’s too big to have hidden on a boat—or raft—or whatever the people used to get here. And I can’t think of any reason why anyone’d want to bring a thing like that on an ocean voyage. And it isn’t all that similar to the mammaloids I’ve seen.”

I made the gesture of inquiry.

“You’d better speak English.”

“It isn’t?”

“No. For one thing, it doesn’t have tits. I can find no evidence that it lactates. The animals on the big continent do. For another thing, it has vestigial scales. They’re hidden in among the warts and bristles.”

“Really?” I took another look at the animal. It was hard to figure out what it looked like. A sloth? Not really. A spiny anteater? No. How about a hairy lizard? Maybe. Or how about a cross between a badger and a toad?

Nothing fit. It was its own kind of creature.

“Do you think it lays eggs?”

“Maybe. I won’t know till I cut it open.”

I decided not to think about that. “Where do you think it comes from?”

“I have no idea. Maybe it evolved here. Maybe it came from one of the islands. Maybe it’s from the big continent. It might have changed after it got here, found an empty ecological niche, and grown to fill it.

“It has been pure hell on the ship. We’ve had too many questions and too little information. We’ve been sitting up there and weaving crazy theories, like a bunch of spiders who’ve been given a hallucinogen.” Marina stood up. “Well, that’s over. I’m going out to check my traps.” She grinned. “It’s just amazing. I have no idea what I’m going to find.”

I stayed behind and watched the animals. They all had the faintly miserable look of creatures in cages. Maybe I was reading in. I wouldn’t like to be where they were. Maybe they didn’t mind.

The ugly-nasty looked at me, then paced some more. Was it getting nervous? I decided to leave.

There were two boats at the dock now, and people were unloading boxes. I went to help.

We finished about the time the sun went down. The river bluffs cast long shadows over the camp. The lake still gleamed, reflecting the blue-green sky. The people I’d been helping thanked me. I went back to my dome and found Derek in the hall outside my room. He was dressed in a pair of white denim pants. The pants were soaked. He had nothing else on. “I’ve just introduced the oracle to hot and cold running water. I’d better get back there. He might drown. Go to the supply dome. Get medium shorts and a shirt. There is no way he can wear that rag any longer.”

“Okay.” I turned and went back the way I had come.

By the time I returned, the oracle was out of the bathroom. He wandered in the hall, wearing a floral-print towel. One of our dome mates—an Asian woman—watched him. She looked bemused.

“Where is Derek?” I asked.

“In the water room. Have you brought me something to wear?”

“Yes. Come on in here.” I led the way to my room. The woman shook her head and went about her business.

I helped him put on the shorts. They were Earth blue with a lot of pockets. The shirt was cotton and short-sleeved: a pullover, yellow with the name of the expedition in bright red Chinese characters. He needed help with that, too.

When the struggle was over, I stepped back and looked. His fly was closed. His fur was only a little disheveled.

Derek came in.

“How do I look?” asked the oracle. “Am I impressive? Is this the way a man is supposed to dress among your people?”

“Yes,” said Derek.

“Look behind you,” I said.

He turned and faced a mirror. “Aiya! It is big! Even my mother the shamaness did not have a whatever as big as this one.” He peered at his reflection, frowning, then baring his teeth. He picked a fleck of something out from between his upper incisors. “I hope Nia comes back soon. I am hungry. It’s hard work taking a bath the way you people do it.”

“You can say that again,” Derek said.

“No,” said the oracle. “Once is enough. I want to go out now. Your houses are too little. I feel as if the walls are pressing in on me.” He pressed his hands together in illustration.

“You take him,” Derek said. “I want to change my clothes and take a nap.”

“Okay.”

The camp lights had come on. They shone over doors and from the tops of metal poles. A hillclimber bumped past over the rutted ground. Someone called to me. I smiled and waved, not recognizing the voice.

We ended on the dock. There were lights on it: little yellow ones that illuminated our feet and the surface of the dock. I wasn’t entirely certain what it was made of. Cermet? Fiberglass? Something gray and rough. It rocked under our weight. The segments rose and fell every time a wave came in.

Bugs crawled around the lights. They were all the same kind: narrow green bodies and huge transparent wings. The wings glittered.

“I am almost ready to eat those,” the oracle said.

I looked down the beach. A person came out of the darkness carrying a string of fish. “Nia?” I called.

“Li-sa! I need a knife.”

I felt in my pocket. “I have one.”

“I have found a place to camp. A cave.” She turned and waved toward the bluff, which was visible only as an area of darkness between the camp lights and the stars. “There is water and dry wood.”

“You are welcome to stay with us,” I said.

She made the gesture that meant “thanks, but no thanks.”

“Then can I go with you?”

“Why?”

I hesitated. How to explain? The day had been too busy. I had gotten too much information. I needed peace and quiet. An environment that was familiar.

“Come along,” said the oracle. “We do not need to know why.”

We walked through the camp, keeping to the shadows, and climbed the bluff. There must have been a path. I couldn’t see it. I followed the sound that Nia made, brushing past branches, clambering over rocks. In back of me the oracle gasped for breath. I was gasping, too.

Nia said, “This is the place.”

I stopped.

“Stay where you are, Li-sa. I know your eyes are almost useless in the dark.”

I obeyed.

“Aiya!” said the oracle. “What a climb! I don’t like the way these clothes fit. They are too tight.”

A flame appeared. I made out Nia, crouching and blowing. The flame grew brighter. She rocked back on her heels and reached for a handful of twigs. Carefully, one by one, she placed them in the fire. It burned in the middle of a clearing. On one side was the river bluff, rising perpendicular and almost bare of vegetation. I made out the cave. It was extremely shallow—an overhang, really.

The rest of the clearing was edged with scrubby little trees. Vines grew up the trunks and over the branches. Entire trees were mantled or shrouded. The leaves of the vines were purple-red.

Nia said, “Give me your knife.”

I unfolded it and handed it over. She cleaned the fish and wrapped them in leaves, laying them in the coals at the edge of the fire.

“There is water nearby. I forgot to ask for something to put it in.”

“I’m not thirsty,” I said and sat down.

“What will happen now, Li-sa? Will your people leave and take you with them?”

“Not yet.” I put my arms around my knees. I looked at the fire and thought, she must have managed to keep her fire-making kit after the canoe went over. Or had she managed to find stones that worked as well as her flint and steel? “They want to exchange gifts. They say there is a village north and west of here, on a little river that goes into the big river. They plan to go there and ask the people if they can stay in this country, at least for a while.”

Nia was silent. I glanced at her.

“Do you think they’ll say no?”

“I do not know what they will do.”

The oracle said, “It seems to me you told us your people live on the western side of the river.”

“Yes.”

I glanced at her again. The broad, low forehead was wrinkled, and her brow ridges seemed more prominent than usual. Her eyes were hidden in shadow.

“Does the village belong to the Iron People, Nia?” I asked.

“I think so. It ought to. This is their country.”

“What will happen if they find you here?”

“I told you before. They will treat me the way all strangers are treated.”

“There is no possibility that you will be…” I hesitated, then used a word than meant to be damaged by accident. There didn’t seem to be a word that meant to be harmed or injured by intent, unless I went to the words that described the quarrels of men.

She looked surprised. “No. They are not crazy. They are not the People Whose Gift Is Folly.”

“What?”

“You know that story?” said the oracle “I have always liked it.”

I looked at him. “What is it about?”

Nia picked up a stick and used it to pull the fish out of the fire. She spat on her fingers, then unwrapped the leaves. “Hu! Is that hot!”

“Is the fish done?” asked the oracle.

Nia made the gesture of affirmation.

“Good.” The oracle moved closer to the fire.

They ate.

When they were finished and licking their fingers, I said, “Tell me the story.”

Nia made the gesture of inquiry.

“The People Whose Gift Is Folly.”

“Yes,” said the oracle. “Tell it.”

“In the far north live a people,” Nia said.

“No,” said the oracle. “They live in the west.”

Nia looked angry.

“I will let you tell it the way you want,” the oracle said. “Even though you are wrong.”

Nia made the gesture that meant “so be it.”

“In the far north live a people. They do everything backward and inside out. The men stay at home. They care for the children. The women herd and hunt.”

“That is right,” the oracle said.

“The people are stupid and clumsy. They tether their animals inside their tents. They live outside under the sky. The rain beats down on them. The snow piles up around them. The wind moans and bellows in their ears.”

The oracle made the gesture of agreement, followed by the gesture of satisfaction.

“When they try to cook a meal, they build the fire in the pot, and when it is burning well, they pile their meat around the pot, against the hot metal. Everything is done stupidly. There are many stories about the ways they get mating wrong. They do not seem to be able to remember what goes where.”

The oracle leaned forward. “There is a story about a man. The time for mating came, and he went out of the village. He found a pot lying on the plain. Someone—some other fool—had left it there. It was well made and handsome. It shone in the light of the sun.

“ ‘How lovely you are,’ he said to the pot. ‘I will look no further.’

“He mated with the pot, and then he returned to his village.

“Later he became angry when the pot did not come into the village and bring him children to raise. He went out and found it, lying where he had left it. ‘Where are my sons, you stupid thing? Where are my lovely strong daughters?’

“He kicked the pot and turned it over. Inside it was red with rust.

“The man fell on his knees. ‘O pot! O pot! You have miscarried! Did I do it? Did my anger kill my children?’ ”

The oracle stopped.

“Is that the end of the story?” I asked.

“I don’t know any more.”

“I have never heard that one,” Nia said.

“Until now,” the oracle said.

Nia made the gesture of agreement. “The story I know is about the woman who became confused at the time of mating. Instead of waiting for a man to come out of the village and into the territory she guarded, this woman found an osupa.She mated with it. I don’t know why the animal agreed. Maybe animals are stupid too in that country.

“Time passed. The woman had a child. The child was covered with feathers and had a tail.

“ ‘What a fine child,’ the woman said. ‘He is not usual at all.’

“The child grew up. He would not learn the crafts of men. Instead he wanted to hunt on the plain. He ran more quickly than any ordinary person. He caught little animals with his claws and teeth.

“ ‘My child is special,’ the woman said. ‘No one has ever seen a child like this.’ She bragged to the other women when she met them. They became angry, because they had ordinary children, who did what was expected of them.

“ ‘We all want unusual children,’ they said.

“The next time for mating came, and they all mated with animals.”

“I don’t know this story,” the oracle said. “I think it is disgusting.”

Nia looked worried.

“If you don’t like it, move out of hearing,” I said. “I want to hear the end.”

The oracle stood up, then he sat down again. “The story is disgusting, but I am curious.”

“I was not thinking,” Nia said. “I have spent too much time with strange people. This is not a story for a man.”

“Nia, you can’t stop now.”

“Yes, I can.”

I looked at the oracle. “Go.”

He frowned. “Do I have to?”

I made the gesture of affirmation.

He got up with obvious reluctance and moved to the edge of the clearing, sat down with his back to us and stared out at the dark.

I looked to Nia.

“There isn’t much more. The women all had peculiar children. Some were like groundbirds. Others were like bowhorns. One woman mated with a killer of the plain. I don’t know how she managed it. Her daughter was made entirely of teeth and claws.

“None of these children wanted to go into the village. They stayed on the plain and hunted one another. They did not learn the skills of people.

“At first the women were happy. ‘All our children are unusual. We have done something that has never been done before.’

“Then they noticed they had no one to help them. And the men in the village noticed the same thing. They went out, both men and women, and pleaded with the children. ‘Come off the plain. Learn the skills of people. We need smiths and weavers. We need herders and women who know how to do fine embroidery.’

“But the children did not listen. Instead they ran away. They became animals entirely.

“The People Whose Gift Is Folly had to turn to each other. They mated the proper way. The women had ordinary children. The men raised them. They were like their parents. Stupid, yes. Clumsy and foolish. But people.” She made the gesture that meant “it is done.”

“Come back,” I said to the oracle.

He returned. We sat quietly. Nia looked depressed, and the oracle looked sulky. I was feeling bothered.

What did the stories mean? Both were about the loss of children. Was that a problem here? Did they worry about miscarriages and damaged children as we did on Earth?

It did not seem likely. This planet was clean. These people had not filled their environment with toxins.

There was another explanation. The stories were about a people who did everything backward. Maybe the message was sociological, not biological. If you want healthy children, be ordinary.

A good message. Relevant and true. Look at me. Look at everyone on the ship. We were not ordinary. Most of us had no children. Those who did had parted with them 120 years ago.

My neck hurt. I rubbed it. “I’m going back down to the village. We need blankets, if we are going to stay the night, and something to keep water in. I have to tell Derek where I am.”

Nia made the gesture of agreement, then pointed. “The path begins there.”

I stood and stretched, made the gesture of acknowledgment and went in the direction she had indicated.

I lost the path in the darkness and had to scramble down over rocks. Branches caught my clothes. Thorns scratched me. I fell a couple of times. Finally I reached level ground; and the lights of the camp shone in front of me.

The main hall of my dome was empty. Voices came through a closed door: a pair of women talking. Farther down someone played a Chinese flute. The performance was live. I could tell by the mistakes.

I flicked on the light in my room and opened the closet under my bed. As I had hoped, it held a blanket.

“Where have you been?” asked Derek. He came in, closing the door after him. He had changed to blue jeans and a light blue cotton shirt. His beard was gone. The skin on his face was parti-colored: reddish brown above and white below. An odd sight. His blond hair was very short.

“You found a barber?”

He made the gesture that meant “it doesn’t matter” or “let’s talk about something else.” “I have been all over camp looking for you.”

“I was up on the bluff. I need your blanket.”

“Why?”

“Nia and the oracle have made a camp of their own. They don’t have anything to sleep on.”

“Why don’t they come down?”

“I didn’t ask. Maybe they feel the way I do. There are too many people here. Everything is too complicated.”

“You don’t know the half of it. I’ll get my blanket.” He left, returning in a couple of minutes. “What else do you need?”

“No pillows. It’s going to be hard enough getting the blankets up the bluff. And the natives don’t use pillows. I’m trying to decide if I want to stay with Nia.”

He tossed his blanket toward me. It unfolded in midair and fell in a heap.

“Damn you.”

“I’ll be back.”

I picked the blanket up and refolded it. Derek returned with another blanket, which he added to the pile. “Janos won’t need this.”

“You think not?”

“The dome is way too warm. I’ll go to the edge of camp with you. I don’t entirely like being inside.”

I remembered stories about Derek. He had a house in Berkeley full of artifacts and books. A lot of books. Most of them were made of paper. Some were new and came from specialty presses. Others were old and fragile.

He worked in the house. Guests stayed in it. If one of the guests was a lover of his, he stayed inside with her. But when he was alone, he slept in a lean-to in the backyard. The roof was a piece of canvas stretched over living bamboo. The floor was grass. He didn’t use a sleeping bag or any kind of mattress. In hot weather he slept on the grass. In cold weather—in the rain and fog of the northern California winter—he used a ragged blanket.

That was the story. I didn’t know if I believed it.

We left the dome and walked up into the darkness under the bluff. I carried the blankets.

“Okay.” He stopped. “This is far enough.” He looked back at the lights of camp. “Did you turn in your recorder?”

“Yes. Goddamn!”

“What?”

“Nia and the oracle were telling stories this evening. I forgot that I didn’t have a recorder on.”

“That shouldn’t be a problem for you. I know your reputation. If something interests you, you’ll remember it.”

“Huh,” I said. “I always like a backup.”

“That also is part of your reputation.” He touched my arm. “I have something to tell you.”

“What?”

“I had a talk with Eddie this evening. He came in after you wandered off with the oracle.”

“Yes?”

“He wants us to go upriver with Ivanova and him. He wants us to translate for them.”

“Eddie is going? A man?”

“That was part of the compromise. We are supposed to send representatives of each of the three factions. For intervention. Against intervention. And the compromise position.”

“Why?”

“To explain our problem to the natives. To give our problem to the natives and ask them for the solution. Since it’s their planet.” I thought I could hear sarcasm in Derek’s voice.

“That might make sense, though I’m not saying it does. But why are they sending a man?”

“Eddie is the chief advocate of nonintervention. And we are supposed to be honest with the natives. We have to explain to them—to show them—what we are like.”

“It’s crazy.”

“Uh-huh. And it isn’t what I want to talk about.” Derek paused. “He wants us to lie.”

“What?”

“He wants us to change what Ivanova says when she speaks to the natives. He wants us to make certain that the natives do not like her argument.”

“No! We’d be certain to be caught. The meeting will be recorded, and someone will check our translation. Maybe not right away, but soon.”

“I told him that. He said we could do it without being obvious. We could slant the words. Twist them just a little. Change the intonation.”

“I can’t believe this of Eddie. I’ve worked with him for years.”

“Do you think I’m lying?”

I looked at him, but saw almost nothing. “No,” I said at last. “What did you say to him?”

“I said the risk was too great, and all we’d gain would be a little time. Ivanova and her people aren’t going to pack up and go home. They want to be on this planet. They’ll go to the next village over and ask permission to land. We’d have to lie again.

“And what is he going to do, I asked him, when the rest of the sociology team comes down? Ask all of them to lie? How long before someone says no and goes to the all-ship council?”

“This isn’t an ethical question for you,” I said.

“I’m willing to lie. But only for my own reasons and only if I’m pretty certain I will not get caught. I won’t lie for Eddie.” He paused. When he spoke again, his voice had changed. The mocking tone was gone. “I am not certain that intervention is a bad idea. Eddie does not come from a culture with a pre-industrial technology. When he goes into the field, he takes a modern first-aid kit and a radio. If he gets into trouble, he can yell for help. He has never been through the kind of experience we’ve gone through, here on this planet. And he has never been through what I went through, when I was growing up.”

“You told him no,” I said.

“I told him maybe. As carefully as possible, in case there was a recorder on. But he thinks he has a chance to pull me in.”

“Why’d you do that?”

“I never make a decision in haste, my love. And I never limit my options until I have to.”

“I don’t understand you.”

He laughed.

I waited.

“Eddie admits that his plan will do nothing except buy time. Interesting, isn’t it, how metaphors of buying and selling have stayed in the language? We buy time. We sell out our honor. He says he doesn’t really know what he is going to do with the time. But he will not let these people go the way of his people in the Americas. He’s willing to risk everything in the hope of stopping that.”

“Huh,” I said.

“Go on up to Nia and the oracle. I think I’ll go and find a bottle of wine. It’s been a long time since I’ve been drunk.”

I climbed the bluff, getting lost again. I have no idea how long I blundered around, tangling myself in bushes, tripping over roots, and sliding down slopes of dirt and stone, then climbing up again, cursing.

In the end I found the camp. I walked into firelight. The oracle looked up. “Your hair is full of leaves. And there is dirt on your face.”

“I’m not surprised.” I dropped the blankets. “There you are. Goddamn! I forgot something to hold water!”

Nia made the gesture that meant “no matter.” The oracle took a blanket and rubbed it with one hand. “I like the texture, though it isn’t as soft as the wool that comes from a silverback.” He wrapped the blanket around himself.

I got a blanket of my own and lay down in the cave. For a while I looked at the firelight, flickering on the stone wall and ceiling.

I woke to sunlight. The oracle sat in the clearing by the fire, adding branches. His clothing—the blue shorts and the yellow cotton shirt—were already a little dirty.

“Where is Nia?”

“She went down to look at her fish traps.”

I got up and pulled my knife out of my pocket. “She’ll need this. I’m going down to the village to eat.”

“You have the luck! I wish I had a place to eat. I am getting tired of fish.”

“Maybe I can work something out.”

This time the trip was easy. The path down was clear. Who had made it? I wondered. Did people come here?

I went to my dome and showered, putting on new clothes: burgundy-red coveralls, a white belt, white socks, and Japanese sandals. I fastened my hair at the nape of my neck and frowned at my reflection. I definitely needed a haircut. But what style? Maybe I should wait till I got to the ship. Meiling always knew what was in fashion. I went to the dining hall.

Eddie and Derek sat together. They were in the shade today, and Eddie was not wearing glasses. I got coffee and a muffin and went over.