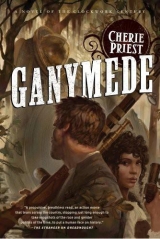

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Mr. Boggs,” she replied.

He extended a hand to help her out of the blower, and she took it. “Here about your brother, I assume?” Every word was pronounced with the oddly emphasized vowels of the Cajuns. His eyes protruded slightly and his stocky frame was approaching fat, but was comfortingly sturdy as he pulled Josephine onto the firmer surface of packed earth at the mud’s edge, then drew Ruthie up as well.

“Deaderick, yes. He’s here in the fort, isn’t he?”

“Where else would we take him? He’s here, and he’s all right for now.”

“Have you any doctors?” she asked.

He shook his head. “No doctors, no lawyers, no teachers, no judges – or anything else too civilized, I’m afraid. They’ve got us in a pickle, pinned down. But it could be worse.” Mr. Boggs extended a hand to Gifford, too, and soon all three of the small blower’s passengers were standing on something closer to terra firma than they’d known since leaving the riverbanks.

“How’s that?” Gifford asked.

“We have fresh water, some food – and ready fishing, right outside the wall – and all the gunpowder and ammunition we can carry.” He returned his attention to Josephine and cocked a head at the other men who’d joined him as part of the welcoming committee. “Listen, ma’am, we didn’t mean to alarm you. We had to check out the newcomers, you know how it goes.”

“You’d be madmen if you didn’t. You know me – and this is my girl Ruthie Doniker, and our escort, Gifford Crooks.”

“I seen you before,” said one of Boggs’s men to Gifford.

“I was here before, out on the island – not in the fort. I fight with the bayou lads, been sent down from Saint Louis. And I got no complaint with Barataria, let me make that real clear up front.”

“Don’t worry about it, son,” said Mr. Boggs. “You’re with Miss Early, and that means you’re all right. I’m Planter Boggs,” he introduced himself, and then his men. “This is Arthur Tate, Mike Hardis, Frank Jones, and Tam Everly. They’re all that’s left from the crew of an airship called the Coyote Black,which is no longer with us.”

The man introduced as Frank Jones was very thin, with ginger-colored hair and a pointed beard. He said, “It was one of the first to go, over there.” He waved a hand to indicate something outside the fort.

And Mike Hardis added, “It went up like a Chinese New Year, though. Took half the dock out. Can’t say she didn’t leave us with a bang.”

“Still, it’s a shame,” said Tam Everly. “I figured I’d run her ’til it was time to retire. Then pass her off to one of my nephews. Won’t be happening now.” Arthur Tate patted him on the shoulder.

“I’m sorry to hear about your ship,” Josephine told the lot of them. “But can one of you, or all of you, I don’t care – can someonetake me to my brother? I’m so tired, I can hardly hold my head up. But I won’t settle down for the night until I’ve set eyes on him.”

“Right this way, Miss Early.” Planter Boggs led the way. “And you there,” he said to Gifford. “Get out of those browns before you get yourself shot. You know what the Good Book says about avoiding the appearance of evil, don’t you?”

“Yes, sir, but the evil was a good disguise to get me in and out of town.” He stripped off the jacket and tossed it into the empty blower, but despaired at the vest and pants.

“Everly, Tate. One of you fellows – can you get him something less … troubling?”

So Gifford Crooks took his leave, and Josephine and Ruthie followed Planter Boggs back into the depths of the old Spanish fort. “He’ll catch up to us later,” Boggs promised. “Come on now, and watch your step. It’s none too bright back here. We’re doing things the old-fashioned way, without any of those electric torches. Trying to conserve our power, you know how it goes.”

He reached for a torch of the ancient variety, a wooden club with fuel-wrapped rags knotted around its head and set aflame. The stink of burning petroleum wafted along, carried and deposited in thick black smoke that stained the walls and the low stone ceiling.

Ruthie stuck close to Josephine, holding her mistress’s elbow as if she was steadying her, and not just looking for an excuse to keep the comforting contact. She asked, “Are we underneath the fort? I do not understand. We went under the wall, but…”

Mike Hardis, a terribly young man with a potato-shaped body but sharp, smart eyes, answered her. “The canal used to be deeper. The Spaniards moved supplies in and out of the fort on flats, all the way from the center inside … out to the bay, and then to the Gulf. But the years have filled it in, as you saw. And now the basement chamber – which is only halfway underground,” he noted as they began to climb a short flight of stairs, “is filled with a century’s worth of tidal mud and backwash. Even so, I can’t say it doesn’t make for a convenient back door. How’d you know to come looking for it?”

Planter Boggs looked pointedly at Josephine. She answered for herself. “In my younger days, I spent a good deal of time at Barataria, and sometimes in the fort.”

“I imagine you still have a number of friends here,” Mr. Boggs said as he led the way up the narrow stairwell, torchlight bouncing off the walls around the rounded corners, up ahead of him.

“Friends and paying customers, if I cared to have them. Most of the men I knew back then are older now, and either wiser or dead. I hope you’ll pardon me saying so, gentlemen.”

On that somber note, they hiked up into a large common room that was so sealed up, it felt to Josephine as if they were still underground, or mostly so. More firelight burned from every corner, some of it chimneyed away by ventilation shafts and columns of brick – but some of it accumulated within the long, flat room with the ceiling so low that the tallest men were compelled to hunch. Some forty or fifty men eyed the newcomers warily, then opportunistically, upon seeing that two were women. And then a name was breathed, somewhere in a back corner.

“Miss Early.”

The whisper carried back and forth throughout the closed, dark nightmare of that cramped and awful place, until the men who stood in their path parted and let them pass.

In French, Ruthie said into Josephine’s ear, “You’re a bit of a legend to them. I had no idea.”

“It was a long time ago.”

“And still they know of you? You must have been remarkable.”

“Still am.”

Cramped and crowded, the room’s walls felt uncomfortably close and the air was stale with smoke, sweat, and the worry of men who knew exactly how much death could be dealt from above and outside. Somewhere off to the west the rat-a-tat-tatof antiaircraft fire shook the fort and was answered by the nearest armored dirigible. Tiny explosions smacked overhead, drilling into the roof and digging into the fortifications. Something heavier landed, and the roof shook. The ceiling quaked and rained mortar dust down on the already silent, already anxious collection of souls below.

“This way,” Planter Boggs pushed. “Never mind the return fire. They haven’t breached us yet, and we’re holding the worst of it at bay from the corners, and what’s left of the other canals.”

“And from the walls themselves,” Mike Hardis added.

Ruthie’s eyes widened. “There are men outside still?”

“Only the crazy ones,” said Frank Jones. “But they’re launching hand-bombs and taking potshots at the boats that slink up close. Somebody has to do it.”

Josephine didn’t want to think about it. “Just get us to my brother. Please. Hurry,” she begged.

“Come through here. It’s this way.”

Another short set of stairs, half a flight down and then up again, and the small band arrived in what had once been a galley – if the leftover counters, racks for pans, and drawers for cutlery were any measure. It’d been converted to a makeshift clinic of sorts. No doctors, no lawyers, no teachers, no judges. No one in charge, but that was always the way of pirates, and no emergency could change it.

The galley was a room full of motion, and the only electric lights she’d seen so far blazed with comparative brilliance above old food-preparation tables, which were now occupied by moaning, groaning injured men. Half a dozen dead bodies were piled in a corner, a fact that was only feebly hid by the application of a filthy tablecloth as a shroud. Limp hands and feet jutted out from the pile, and warm, sticky bloodstains showed up where the wounds were not yet finished leaking. Ruthie put her hand over her mouth and tried not to gag. Josephine would’ve done the same – the smell of urine and burned flesh and gunpowder and blood was almost more than she could stand – but she’d spotted Fletcher Josty in the room’s middle, beside a decrepit pump-water sink that, against all odds, was still working.

The bayou guerrilla yanked and shoved on the handle and water did veritably appear, though it wasn’t as clean as one might hope. Many hands held out bowls, cups, and dirty rags, hoping to collect some of the liquid for refreshment or cleansing.

Josty pumped furiously, trying to force the men to take turns. “One at a time, you bastards! There’s water to go around, but you have to wait your turn! I can’t make it come out any quicker,” he grumbled.

“Fletcher!” Josephine cried.

The room stopped for an instant, as even the eyes of the wounded turned at the sound of a woman’s voice. But another jagged cry rang out and the chorus of aching voices rose behind it, and the sad scene carried on as before, except that Fletcher quit pumping. He grabbed the nearest able-bodied soul and shoved him at the pump, ordering, “Keep that arm moving. Keep that water flowing.”

Then, as he abandoned that wretched post, he danced between the tables and the sprawled arms and legs. “Miss Early,” he said, looking like he would’ve tipped his hat if he’d had one on. This free man of color was as filthy and smeared with soot as everyone Josephine had seen so far, but she was overjoyed by the sight of him, and it was all she could do to keep from hugging him.

Instead she grasped him by the shoulders and asked, “Deaderick?”

“In the cellar, ma’am.”

“Oh … oh, God…”

“No, no. He’s still alive, it’s just cooler down there, that’s all, so that’s where I’ve stuck ’im. Some of the men who are stable, and needing to rest … it’s all we could do to make them comfortable. It’s more sheltered, too, I think. If Texas brings in anything bigger, or shoots anything worse, we might be digging for cover.”

“Then to the cellar. Now.”

Planter Boggs gave Josephine and Ruthie a little bow and said, “Ladies, if you’ll excuse me.”

“Of course,” the madam said without looking. She was already trailing behind Josty, and Ruthie behind her.

And down into the cellar they followed – back to the level where the canals came and went. A large round of artillery connected with a thick mortar wall somewhere to the east. Josephine thrust out an arm to brace herself. The whole world shook, and it seemed like even an old fort built by Spaniards to survive the Second Coming couldn’t stand beneath the onslaught.

But stand it did.

And in the cellar, on the old concrete docks that were barely raised above the mud, Deaderick Early lay between two other men in similar states of injury and consciousness.

She ran to his side, trying to keep from disturbing the others. Without stepping on them or kicking them, she knelt beside her brother and took one of his hands in hers – clasping it to her breast and examining the damage with as much cool reserve as she could muster. She tried to keep the panic out of her eyes when Deaderick opened his own.

“I knew it,” he said unhappily.

“You knew what?” she asked. It was a relief to hear him talk, even to hear him complain. But the bubbling red across his chest was not a relief, and his face was blanched and pale beneath the burnish of his complexion. Every muscle from his forehead to his chin was stretched tight with pain.

“I knew you’d come. Whether or not anyone told you not to. That’s why I told them not to tell you. Josty did it, didn’t he? Damn fool.”

Ruthie seized Deaderick’s other hand and held it up to her cheek. “ Bien sûrshe came, you ridiculous oaf!”

“Christ Almighty, not you, too.”

“ Oui, moi aussi. Now, hush and let us take care of you.”

“I don’t need you to take care of me.”

Josephine released his hand so she could explore the injuries with her fingers. Gently, thoroughly, and trembling, she unpicked his buttons and revealed the sad, masculine attempts at bandaging. An ash-colored rag that might once have dried dishes was balled up and compressed against the largest of two holes, or so she learned upon lifting it. It stuck, blood drying to chest hair, and Deaderick grimaced.

“Woman, let it alone! If you leave it be, it’ll stop bleeding.”

Fletcher Josty hovered into the scene and contradicted him. “It hasn’t stopped yet, not for good. Not like the other one. Rick, I’m starting to worry.”

“Save your worry for yourself, because when I’m up again, I’m going to tan your hide for getting Josie involved.”

“Oh, shut your mouth. You’ve met your sister, haven’t you? Like we could keep her away.”

Just then, someone shouted from the far end of the cellarlike nook. “All right, you goddamn pirates have gotten your way. I’m here, and you won’t do any better – not for trying. Who needs attention?”

“Are you a doctor?” Josephine asked like lightning.

“Used to be. I’m starting down here and working my way up like the free men of the air have demanded. So tell me,” said the man. “who’s in the most danger? Has no one sorted them out, grouped them by seriousness of condition?”

Fletcher rolled his eyes and said, “This ain’t no hospital, mister. It’s been all we could do to get ’em out from underfoot!”

Josephine stood and shoved Fletcher Josty aside. “Never mind him. Get yourself over here, Doctor, if that’s what you are. My brother has two bullets in him, and he needs your assistance now.”

“Only two? He’s one of the better cases.”

“I’ll pay you. Whatever you think you’re worth. I … I own a boarding house, in the Quarter. Get over here and fix my brother, and I’ll see to it that you have a week you’ll never forget, do you understand me?”

“No, but I’m open to the explaining,” he said, coming toward her. He was an older man and, by the look of him, a lifelong alcoholic. The skin across his nose was the color of blisters and streaked with broken blood vessels; his eyes were likewise shot through with red, and his face hung off his skull with a droop like a hound dog’s.

“Get over here, then. Fix this man.”

“No,” croaked Deaderick. “There’s worse up there, men who need the attention more.”

“Shut up, if your woman’s willing to pay. I was dragged out of bed for this, and I’ll help who I like – and who I’m paid to patch. I said I’d start in the cellar and work my way up, and you’re as likely a patient as the next man, aren’t you?”

“What kind of doctor are you?” Josephine thought to ask, feeling suddenly uncertain about this.

“A genius or a quack. Either way, I’m Leonidas Polk, and I’ll patch this fellow up if I can, but you need to get out of my way. Good Lord, they’ve just been letting you bleed?”

Deaderick replied, “No. But the one bullet hole, it don’t want to plug up right.”

“You can stitch it, can’t you?” Ruthie asked, still squeezing Deaderick’s left hand as if she could lend him some of her own life force.

“Stitching won’t do any good on something like this,” he said, whipping out a pince-nez and examining the bloodiest spot on Deaderick’s chest, where the blood had sensed an opening and was beginning to flush afresh. “Do you have any other conditions? You’re not a dust sniffer or an absinthe drinker, are you?”

“No…”

“Is the bullet still inside?” he asked.

“No, I don’t think,” the patient replied. “Straight through, both shots. If the blood would stop coming, I think I’d be all right. I could stand up and see myself out,” he swore, though no one believed him.

Ruthie kissed his hand and said, “Stop it, you silly man. You’ll lie there and get better. The doctor will fix everything, won’t he?”

“Son of a bitch, ma’am. Don’t tell him that,” Dr. Polk swore.

“But you’ll do what you can,” Josephine told him more than asked him.

“I’m going to need some gunpowder and a match.”

Deaderick swallowed hard, his Adam’s apple bobbing in a nervous slide. “I was afraid of that.”

“Afraid of what?” his sister demanded. “Afraid of what?”

Dr. Polk asked, “How long has it been since you were shot?” He looked again at the wound. “Five hours? Ten?”

“Thereabouts.”

“We’ve got to cauterize it. I’d break it to you more gentle, but there isn’t time. Ma’am, get me some gunpowder and a match.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It’s best that you don’t.”

Josephine hauled herself to her feet, confused and even dumbfounded by how difficult it was. She staggered toward the stairs that led to the galley, and within a few minutes she’d talked herself into a dead man’s powder pouch and a box of matches. Horrible though it was, she had a feeling she knew where this was heading … and she couldn’t stand it. But this was a doctor – maybe a quack, maybe a drunk, but the only one present, roused, bribed, and impatient – so she’d do as he asked, because heaven help her, she didn’t know how else to proceed.

Dr. Polk reached for the gunpowder. “Ladies, avert your eyes. For that matter, you might want to do the same,” he told Deaderick. Then he spilled a tiny trail around the wound and on it – a black sprinkle of glittering stuff, barely a dusting. “I mean it,” he reiterated. “Look away. All of you.”

He struck the match.

Deaderick screamed.

And Ruthie passed out cold.

Eight

The captain said, “Goddamn, Kirby. Your acquaintances weren’t half-kidding.”

“Nor was the lady from the taps,” the engineer graciously replied.

Everyone gazed out the thick glass windscreen in silence, even Houjin – whose incessant questions had drawn up short when confronted with the wreckage at Barataria Bay, where the great pirate Jean Lafitte had established his empire … an empire that had stood a hundred years and might have stood a hundred more, were it not for Texas.

The Naamah Darlingdrifted slowly past the big island’s edge, steering clear of the thin, curling towers of black smoke that still coiled from the ground, and avoiding the other ships flying nearby, likewise creeping up to the edge of the destruction and gawking at what was left. Everyone gave everyone else a clear berth, since the details were still so few, and the devastation so very awful.

Below, the pipe docks were melted and twisted into a crumpled parody of their prior shape, and the burned-out hulls of dirigibles were flattened against the ground or in the water. Their stays jutted like the ribs of huge dead animals, like the big stone bones of long-extinct beasts from another time. Dozens of ships. Maybe fifty or more, charred and useless.

They dotted the landscape in lone craters and in clusters. What few buildings the island had boasted were burned or blasted into obsolescence, leaving the whole scene below a weird panorama of a place cleansed by fire.

Even from the Naamah Darling’s height, the captain and crew could see brown-uniformed Texians moving about below. Digging trenches. Toting corpses to burial – or here and there, moving a survivor on a stretcher. Cly wondered why they bothered. Surely anyone found on Barataria would be tried and jailed at best, hanged at worst, for being found on the island and firing back at the Lone Star’s airships.

But there was much he did not know about the situation, and the uncertainty left an uncomfortable warm spot in his stomach, as if this impersonal attack on someone else meant more to him, personally, than it ought to. It would be an exaggeration to say that the sight of the blighted island churned his stomach. He hadn’t visited it in years. But it’d been one hell of a bustling place once – a rough-and-tumble spot, to be sure, but one where a certain kind of man could find a certain kind of freedom.

When he pulled out his spyglass and aimed it at the mess below the ship, Captain Cly could see alligators, nearer to the island now than they tended to creep in daylight. Their long brown-black forms lounged as motionless as logs – and easily mistaken for the same – but their bulbous eyes and heavy tails twitched in the afternoon sun.

“Are those—” Houjin finally found his questions. He’d found a spyglass, too, and was likewise watching the water’s edge. “—alligators? Down there, look – one just dove under the water, and it’s swimming, you can see it. Right there, Captain.”

“Yes, that’s an alligator.”

“It’s very big, isn’t it? It looks almost as long as that canoe.”

“They’re sometimes very big, yes.”

“They aren’t afraid of people, are they?”

He swallowed. “The smell of death is drawing them out – even more than usual.” And before Houjin could demand to know what he meant by that, the captain changed the subject. “Anyway, look what else is going on – over there in the water, around the old island docks.”

“Let me see,” Kirby Troost said to Houjin, who handed over his spyglass. Upon getting a gander, the engineer said, “A handful of strange-looking flatboats, and something bigger. And nets. Looks like they’re dredging for something. Maybe they sank something they didn’t mean to.”

“Maybe. People call those flatboats blowers. Some spots out in the bayous, and in the marshes, it’s the only good way to travel. The boats are nice and light, see. And the fans just blow them along.”

Houjin grasped the situation instantly. “And since the fans are up, out of the water, their blades don’t get clogged by the grass!”

“Atta boy,” Cly told him. “Any other propeller or engine you stick in the water is done for.”

Things might have digressed into a conversation about transporting men and goods through inhospitable terrain, but a loudly shouted, “Ahoy, Naamah Darling!” jolted the chatter in another direction entirely.

All the men on board tore their attention away from the scene below and looked around, trying to spot the speaker. The captain pointed out to the west and nudged the steering levers to better point the dirigible toward another airship – one much closer than they’d realized.

Someone had snuck up on them.

The ships were near enough to each other that Cly, Troost, Houjin, and Fang could plainly see three men in the cockpit of the other dirigible. Houjin waved. One of the distant men waved back. The voice came again, and this time its source was obvious: a large electric speaker mounted to the exterior of the hull.

“You’ve entered airspace deemed restricted by the Republic of Texas. I have to ask you to accompany us to a landing dock a short ways east, at Port Sulphur. Do you agree to comply at this time?”

Cly and his crew members looked back and forth between one another.

Houjin, always the first with a query, asked, “Captain?”

Fang shrugged, and Troost did likewise. The engineer said, “We aren’t carrying any contraband. We can play dumb.”

Thoughtfully, Cly said, “We’re from out of town. Nothing bad on board. No reason to put up a fight or make a stink.” Out the windscreen he could see more Texian ships, approaching the other gawkers in the same way. “They haven’t singled us out. They’re just clearing the area. Sure, let’s see what they want. I’m not familiar with Port Sulphur, but maybe they can point us at a good machine works.”

He returned his attention to the Texian ship, waved, and nodded. He added a thumbs-up for good measure and held out one long arm as if to say, After you!

One by one, they buckled back into their seats and waited for the Texian ship to lead. When it did, they followed at a respectful distance – but close enough to make it plain that they meant no trouble, and were abiding by the Republic’s orders.

Houjin said, “I don’t like this, sir.”

“I’m not highly keen on it either, but it might work out. Maybe we’ll learn something. And we’re headed in the right direction, anyway. There’s nothing to worry about, you hear me? We haven’t been up to any mischief, and they aren’t shooting at us. Mostly, I think, they didn’t want us watching what they’re doing in the bay.”

“That’s my guess,” Kirby Troost observed quietly. “And it backs up what my acquaintances and your tapper lady said.”

“How’s that?” asked Houjin.

“Texas took Barataria apart with a goal in mind. They’re looking for something – something they thought the pirates were holding or hiding.”

“Something in the water,” Cly added.

The boy frowned. “Some kind of ship? But you were just saying how hard it is for ships to—”

The captain shook his head. “I know what I said. But I also know what I saw. This has the stink of a military operation all over it.”

It was Troost’s turn to frown. “Isn’t everythingTexas does in New Orleans a military operation?”

“Mostly they’re here to keep the civil order. Police work, and the like. They occupy, they don’t govern – that’s still left to the Confederacy. And this wasn’t police work. This was army work. I wonder how much we can get them to tell us about it.”

Fifteen minutes later, they were setting down at a large industrial pipe dock on a promontory near a wide canal, at the edge of the marshy swamplands, like almost everything else between the city and the Gulf. Being careful to preserve every appearance of innocence, the captain disembarked and used the lobster-claw anchor to latch the Naamah Darlinginto the nearest slot.

As he did so, he was approached by a Texian who might’ve been tall by anyone else’s standard, but was merely neck height to Andan Cly. The beefy blond was wearing the local version of the brown uniform – pants and boots as usual, but jacketless and with the sleeves of his white shirt rolled up past his elbows and unbuttoned halfway to his waist. It was the captain’s opinion that telling any Texians anywhere to wear any uniform was an act of futility, but it wasn’t his army and he didn’t say anything except, “Hello, there,” when the man stuck out his hand for a shake.

Handshakes accomplished, the Texian said, “Hello back at you,” with a heavy Republican accent. “And I want to thank you for your cooperation. Not everyone has been so quick to leave when asked. I’m Wade Bullick, captain of the Yellow Rose,” he said, waving a hand at the ship that had escorted the Naamah Darlingout of Barataria’s airspace.

“Andan Cly, captain of the Naamah Darling.”

“Pleasure to meet you, and I do beg your pardon about all this. We had ourselves an incident at the pirate bay, and right now we’re in the middle of getting it all cleaned up. You know how it goes.”

“I suppose I do.”

“And I don’t suppose you had any business there yourself?” Bullick asked casually.

“None whatsoever, I assure you. We saw the smoke, is all. And I won’t lie – we heard rumors, on our way east.”

“On your way coming east? Most folks come here by flying west. Where do you all hail from?”

“The Washington Territory,” Cly told him. He also took this opportunity to provide his ship’s licensing papers, which he’d stuffed into his vest before leaving the ship. He knew they’d be asked after, and it was always better to offer such things when one was innocent of any wrongdoing. “We’re registered out of Tacoma.”

Wade Bullick examined the papers, and Cly noted that the man either read very quickly or made only a show of reading – and he couldn’t tell which. “Everything does look to be in order here. Might I ask why you’ve come to the good land of Louisiana, Captain Cly?”

“Supply run, mostly. We serve the little frontier towns up and down the Pacific Coast, and I homestead in a tiny port town called Seattle,” he exaggerated only slightly. He preferred to think of it as an optimistic prediction. “Also, this bird was built to move cargo I don’t care to carry, so I was hoping to find one of your Texian machine shops and get her all fitted up for regular trade and supplies. You’re welcome to climb inside and take a look.”

“You got crew with you?”

“Three men – my first mate, but he’s a mute Chinaman and can’t tell you about it; an engineer; and a young fellow who’s apprenticing to ride aboard more permanent-like. We don’t have cargo right this moment, nothing but our own possessions. We flew down empty, with intent to load up before heading home.”

Captain Bullick went to the stairwell and climbed halfway up, poking his head into the interior and looking around. Cly couldn’t see if anyone waved at him, swore at him, or stuck out a tongue, but he trusted that nothing too out-of-the-ordinary took place outside his line of sight. He also trusted that Bullick had noticed the tracks running along the ceiling, and the empty sacks he’d once used to move the blight gas.

“I see what you mean,” the other captain said as he retreated back down to ground level again. “Been moving things to make other things, have you?”

“Once upon a time,” Cly confessed. “But I’m giving it to you straight – that’s not what this is about, and not what we’re here for. And I really am hoping you can make me a recommendation for a shop where I can get some of that unnecessary gear stripped out.”

“All right, then, I’ll take you at your word – since you’ve been so agreeable thus far, and all. And as for Barataria, I don’t blame you for wanting to come take a look. It left a big ol’ hole in the marsh, didn’t it? Not that I expect the fun’s been rooted out for good.”

“Excuse me?”

“Aw, come on. Between you, me, and the entire Gulf coast, everybody knew what was going on out there.”

Cly retrieved his papers and stuck them back in his vest. “I don’t suppose there’s any chance you could tell me what all the hoopla was about, is there? Gossip was all over the taps, but that’s all we heard. Nothing but gossip.”

“Honest to God, I don’t have much more than that to share. A couple nights ago, the bay went up like firecrackers – and yesterday Colonel Travis McCoy called everybody out to help clean up what was left. I’m not a military man myself, except in the loose sense. I mean, I’ll show up if they offer me Republican money to fly around like I was going to anyhow, that’s for sure. But I’m no fighter, and no Dirigible Corpsman. McCoy told the fellas like me to act with Texas authority and keep the sky cleared. And now you know about as much as I do.”