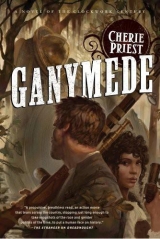

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Ruthie selected a folded sheet of paper. She unfolded it and handed it to Andan Cly.

It depicted the interior workings of a ship, but not one like anything he’d ever seen before. It looked like fiction, there in his hands.

These lines showing gears, and valves, and portals; these careful engineering sketches showing bolts, and curved walls, and compartments for flooding or pumping; these enormous rooms that seated six to eight, with side and bottom holds for ammunition – and tubular sleeves for explosives and fuses.

He did not look up from the schematics when Hazel began talking again, but he listened to her as he perused the pictures with wonder.

“Then McClintock caught Watson red-handed, with telegrams and instructions from the Union army. Whether Watson was a double agent all along, or he simply wanted the bigger payday from the bigger army, no one knows. But he was all set to sell their research to the North, and McClintock wouldn’t have it. They fought, and Watson shot McClintock through the heart before trying to flee inside the vessel he’d helped create.

“But Watson was a designer, not a skipper. He understood the mechanics of the beast, but not the nuance of making it sail – even if that werea task a single man could accomplish. The ship sank halfway across Pontchartrain. Watson drowned.

“But his message had already gone back to the Union engineers, who knew the craft existed. They came to investigate – only to be caught by the Texians, who were also looking for the ship.”

“How did Texas know about it?”

Hazel nodded approvingly, as if this was a good question. “It had been made with Texian technology, and Texian machinists, so they knew it was out there somewhere. They didn’t find, it, though.”

“And your people did?”

Both of the women smiled, identically and in perfect time with each other. Hazel continued. “It took three weeks of looking, but the ship was found and lifted by a group of guerrillas in the bayou … the free men of color who fight Texas and the Confederacy from the shadows. They hauled it to a different shore and hid it there, where it remains now – waiting for the right man or men to take it all the way to the ocean, where it was always meant to go. And that,Captain Cly, is the story of the Ganymede.”

Cly finally looked up from the intricate engineering sketches. He looked each woman in the eye and said, “You want me to fly a ship underwater.”

“Once we can man-haul it to the river, yes. The Mississippi is deep enough to take it, and once you’re in the river, you’ll have slip past Fort Jackson and Fort Saint Philip. From there, it’ll be smooth sailing straight out into the Gulf of Mexico.”

“In a ship that’s drowned … how many men?”

“ Ganymede? Oh, hardly any,” Hazel dismissed his concern hastily, and with a wave of her hand. “Only Mr. McClintock, so far as we know. As you can see from those plans, Ganymedeis a much stronger design – a much better ship than the ones that came before. Learning how to create a ship like her … it was costly, yes. But the end result is thismajestic creation. And it will end a war, Captain.”

Ruthie rose and left her chair, approaching Cly and crouching beside him. With her elegantly gloved hands, she called his attention to various highlights on the schematics that sat across his lap.

“Right here, you see? This is the steering mechanism, and the power system for the propellers. They were designed like thrusters on an airship.”

“I see that, sure. But there’s no hydrogen to keep steady. No gas to maintain, or to power the thrust.”

“But of course there is gas, monsieur! The gas is the air you breathe. It is pumped and cycled, through these vents here, by this tube. If the men breathe the same air too long, it makes them sick. They faint, and they die.”

Hazel confirmed, “That’s one of the hard lessons learned from the Bayou St. Johnand the Hunley. The men inside must have fresh air, drawn down regularly. The air within the cabin cannot support them forever.”

“So this—” He jabbed a finger at one long set of pipes, and drew it along the lines. “—these pipes don’t stay above water, not all the time? So you don’t have to keep this breathing tube up above the surface?” It reminded him of Seattle, of the system that likewise drew fresh breathing air down underneath an inhospitable surface. They did it the same way, essentially. Tubes bringing in the fresh air for four to eight hours a day, always keeping it moving, never giving it time to grow stale.

Ruthie nodded. “The tubes do not stay up. You can close them from within, like this.” She indicated a rubber-sealed flap that was manipulated by a hydraulic pulley. “There is one main breathing tube, with fans to draw down the air – and an emergency tube in case the one should fail. But they can both be shut so that the ship can sink and hide.”

“For how long?” he asked.

The ladies paused, but Hazel replied. “We’re not certain. Twenty or thirty minutes, at least.”

“So really, it’s a ship that can hold its breath for half an hour at a time.”

“Yes!” Ruthie rose to her feet and clapped. “You see? Josephine said he would understand. She said we needed an airman, and she was right!”

“But what about the original crew? You said it’s been tested, out on the lake. Where are the guys who know how to pilot this thing already?”

Hazel handed him another sheet with a different angle on the Ganymede’s inner workings and said, “Most of them were captured. Two men were sent off to a prisoner-of-war camp in Georgia, and three were sent to the barracks here, but escaped and went back to New England. And the man in charge was shot for treason.”

“Treason?”

“He was from Baton Rouge – a Confederate deserter who’d come to work with the bayou boys. Name was Roger Lisk, may he rest in peace.” Hazel leaned forward, restlessly arranging and rearranging the remaining documents. “Without the crew, and without the men who created it, the Ganymedeis a big hunk of metal full of potential … but precious little more than that. The bayou boys have all the information – all these schematics, and instructions. But they’re soldiers and sailors by trade, and sailors haven’t performed well so far, when it comes to keeping the ship afloat and running. And the Union is not so convinced of its value that it’ll risk its own engineers and officers on the project – not unless we can get it to the admiral.”

But Ruthie appeared more hopeful, now that the ball was rolling. “Josephine said no one could work the Ganymedebecause only the sailors were willing to try. But Ganymedeis not built like a boat. She is built like an airship, one made to fly in the water, not in the clouds. Josephine said we needed a crew of airmen. Airmen would know how to make her go.”

“Now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves,” Andan Cly cautioned. “I can see that you’re right – partway right, at any rate. Whoever built this bird,” he said, then corrected himself. “Whoever built this fishdrew a lot of inspiration from an airship, that’s true. The controls are similar, or so I gather from looking at this. And the shape is more or less the same, with fins instead of small steering sails, and the propeller screws instead of the left and right thrusters. Hmm.”

“Hmm?” Hazel prompted.

“Hmm,” he repeated. “I don’t know anything on earth about sailing, but I understand it’s pretty different from flying. The principle is easy to sort out, but the principle and the practice are two different things.”

Ruthie leaned on the edge of the desk, halfway sitting upon it and halfway resting her bustle there. “It’s true. It’s all true – and we know you are an airman, and not a sailor. But can you make it swim?”

“I … I don’t know what to say.”

“You told Josephine you’d take the job,” Hazel reminded him.

“I didn’t know I was agreeing to a job that might get me and my crew drowned at the bottom of a river, and that’s part of my trouble. If it were just me, that’d be one thing. But a boat like this … it’d take at least two or three men to control her. Maybe more. I’d have to ask my crew members how they felt about it. We’d need to see it in person.”

“That can be arranged!” Ruthie exclaimed. It was clear she’d made up her mind already: this was going to work, all would go smoothly, and the problem was all but resolved.

Hazel was not so confident, but she was willing to risk a shred of hope. She told Cly, “We can take you to it, tonight if you like. Josephine is there, out at the lake with her brother.”

“Wait a minute, wait a minute. Hold your horses, ma’am. Let me go back to my rooms and have a chat with my men, all right? I’ll tell them what you’ve told me, and they can decide whether or not they want to take the chance.”

“But, Captain!” Hazel objected. “You can’t go running around willy-nilly, spreading the story around the Quarter!”

“And I won’t. But I won’t ask my men to risk their lives spying and smuggling against two governments at once, not without knowing what they’re risking. For what it’s worth, I expect they’ll be willing to help. Two of my crewmen are Chinamen, without any more political allegiance than I’ve got, and the other is Kirby Troost, who you met downstairs, He’s always game for anything – the more unlikely and dangerous, the better – and if the prospect of friendly women is involved, you may as well call him sold. So they can make up their own minds, and even if they decide they don’twant in, you can sleep well knowing they won’t have any interest in handing you over to Texas, either.”

Hazel chewed at her lip and tapped Josephine’s silver letter opener up and down on the desk’s edge. “We were hoping for a definite commitment.”

“I’m sorry, but that’s the best you’re going to get right now.” He glanced out the window. “It’s almost sundown, and the curfew will be settling soon. I know you’re not too worried about it – and honestly, neither am I – but if we want to hang around without drawing extra Texian attention, we need to follow the rules. Until we break the ever-living hell out of them, anyway.”

Much as they didn’t like it, the women had to admit that this was reasonable. Ruthie said, “In the morning, then. Tell me where you are staying, and I will come for you. I will take you out to Pontchartrain, and you will see Ganymedeup close, and crawl inside, and show the bayou boys how to make her swim.”

“That sounds fine to me,” he told her. “We’ve got a couple of rooms over at the Widow Pickett’s on the other side of the Square. You can come collect us there in the morning. So if you’ll excuse me, I’ll go round up my engineer and … On second thought, you know what? Keep him. Or send him along when he’s ready to come back.”

With that he climbed to his feet, returned the papers he’d collected, and excused himself.

But Hazel said, “No, you keep those. And this one, as well.” She handed him another sheet, detailing the propulsion screw and the diesel engine, as well as its exhaust system. “Look them over. Make yourself familiar with them. And for the love of all that’s holy, don’t let the Texians see them.”

Nine

Ruthie Doniker knocked on Andan Cly’s door brighter and earlier than he truly cared to see her, but he’d told her “morning,” and so it was morning when she came calling. When he opened the door, she stood there swathed in a green cotton dress too formfitting to be called plain, with a very light jacket that had a high cream-colored collar cinched around her neck. Before the captain had a chance to greet her, she said, “It is time to leave for your day at the lake, Captain Cly.”

“No kidding.” He blinked blearily. He was awake, but he hadn’t been for long. Not long enough to shave or wash his face, and only barely long enough to realize that Kirby Troost hadn’t come back to the room. “Well, I guess you can come on in while I get myself together.”

“Merci,”she said, and sidled past him.

“Have a seat wherever. Give me a minute, would you?”

He pulled out his razor and tried to forget that Ruthie was present and looking at him. It was easier said than done. Every time his eyes slipped away from his own face in the mirror, he caught her reflection and felt strange about it.

At some point, he paused with the razor braced under one cheek and asked, “So, Kirby. I guess he stayed at the Garden Court last night?”

“I guess he did. Marylin took care of him. He came here with me.”

“Oh. He did? Where is he?”

“Awakening your other crewmen.”

As he drew the razor across his skin, Cly realized that she’d never asked him if they’d agreed to take the job or not. Ruthie was assuming they would take it, as if she could bend reality to meet her whims.

He was glad he wouldn’t need to disappoint her.

The night before, he’d sat with Fang and Houjin after supper, showing them the schematics in the privacy of their room, where no Texians, Confederates, or other unwelcome eyes might take a look. Houjin had responded with enthusiastic glee – he would’ve risked a coin-flip’s chance of drowning for the mere opportunity to get a look at the Ganymede,much less crawl around inside it. His passion for all things mechanical would draw him to the lake even if they told him it’d cost a dollar and he’d get a beating when he arrived.

Fang had been his usual unflappable self, nodding his agreement to investigate the craft and, later, when Houjin could not see his hands, signing to the captain, Very dangerous?To which Cly had shrugged a maybe. Then, while the boy’s nose was still stuck in the diagrams and drawings, Fang had added, I will do this, for the Union.

Cly signed back, Didn’t know you cared one way or the other.

I care for the West. If the South wins, and claims new states, they will be states where men can be owned as slaves. If the North wins, maybe the new states will be … He paused. Not much better. But where freedom is declared, it can be negotiated. Besides, I liked Josephine. Smart woman. Easy to agree with.

“Easier to agree with her than to argue with her, that’s for damn sure.”

As Cly finished up his shaving, wiping down his face and neck, a knock on the door was followed shortly by the entrance of Fang, Houjin, and Kirby Troost, who touched the edge of his hat in Ruthie’s general direction.

Ruthie stood to her full height – three inches taller than Troost, though that was emphasized by the boots she wore – and announced, “If everyone is ready, we should go catch a carriage.”

“Shouldn’t we just grab the street rails, instead?” Cly asked. “Surely that’d be faster than a cabriolet.”

“A carriage to the edge of the Quarter, and then we can take the rails to the far side of Metairie, but no farther. Where we go beyond the City of the Dead … only trusted eyes may lead us.”

Together they followed Ruthie’s lead down to the street, where she nabbed a carriage in the blink of an eye, even though she needed a larger transport than was usually running. Before long, they were back at the street rail station where they’d first entered the city, and then on the car to Metairie, to Houjin’s continued joy.

On the way, Kirby Troost sat beside the captain. When Ruthie stood at the protective guardrail, likely out of hearing distance, the engineer asked quietly, “Are you sure about this?”

“No.”

“Me either. Did they tell you about what happened to Betters and Cardiff?”

“Who are Betters and Cardiff?” Cly asked.

“The Texians who went missing. They’re the reason New Orleans has a curfew.”

“No, the ladies didn’t mention it.”

“Josephine knows,” Troost said softly. “The girls at the house say she was there when they died. Do you know they’ve got a rotter problem, here in New Orleans?”

Taken aback, Cly gave Troost a hard stare of uncertainty. “That’s impossible. No gas, no rotters.”

“Impossible or not, that’s what they sound like to me. Except they don’t call ’em rotters here. They call ’em zombis. And I don’t think they’re made by the gas. I think they’re made by the sap.”

Cly considered this and said, “We’ve known for a while that the drug makes people sick, if they use it too long.”

“I think it does worse than make them sick. I think it kills them, and keeps them upright, just like the dead in Seattle. All I’m saying is, when you meet back up with this lady friend of yours, you should ask her about it. The girls say she saw the whole thing. Her and some voudou queen, but I don’t rightly know what to make of that part.”

The captain stayed hung up on the undead particulars. “I’m not saying there aren’t any rotters outside the city, Troost. Ten minutes talking to Mercy Lynch’ll tell you that much. But those rotters happened because a dirigible crashed, and the gas got loose – poisoning the air where all those people were. That was a mess of an accident, but I don’t think that could happen around here, not without people noticing it.”

“I’m not arguing with you. A big load of hungry dead folks didn’t just appear one night down by the river. They weren’t here ten years ago, were they?”

“If they were, I never heard about it.”

“That’s what I mean,” the engineer said. He was wheedling now; he had an idea and he was determined to share it – by verbal force if necessary. “They didn’t spring up overnight, but they’ve been happening gradual-like. One or two sap-heads, here and there, going so deep into the drugs that they didn’t ever come back. Then what happens if another one or two, here and there, does the same thing? And another few?”

“It’s a stretch, Troost.”

“I know it is. But it’s not a bigstretch, and I don’t think I’m wrong. The streets aren’t crawling with them, not like in Seattle, but they’re a problem down by the river, and the Texians are on a rampage, trying to wipe them out and make the place safe again.”

“How do you know that?” the captain asked.

“You saw that Texian in the lobby, the fellow who practically lives there? His name’s Fenn Calais, and as long as you’re buying, he’s talking. You know what else he told me?”

“Go on.”

“He said that the raid on Barataria was an official operation, and Texas was looking for a ship – something they thought the pirates might be hiding, or in the process of smuggling out to sea. And when we saw them from the sky, watching over the bay, they were poking around in the water, weren’t they doing just that?”

“Doesn’t mean they were looking for—” He chose not to say the name aloud. Just in case. “—the ship we’re looking at.”

“All I’m saying is, I hope we’re not biting off more than we can chew.”

Cly grinned. “You don’t hope that. Not for a second. You hope it gets so messy, you can make your own fortune.”

“Goddamn, sir. You know me entirely too well.” Troost rolled a cigarette and stuck it between his lips, then lit it and puffed on it the rest of the way to Metairie.

At the Metairie station, they all disembarked and were met by a handsome, heavyset black man named Norman Somers. He greeted them wearing denim pants, a linen button-up shirt with a vest, and a big smile that did not appear practiced or false. If he was a spy or a man with a covert mission to attend, he was a very fine actor – or so Cly thought.

Ruthie gave Norman a kiss on the cheek, which he returned. “You must be the captain and crew,” he said to the rest of those assembled. “I hear your ship is out here at the Texian yards, over yonder.”

“Just on the other side of the station, that’s right,” said Cly. “Having a little work done while we’re in town.”

“You’ve picked a good shop. Mostly it’s run by Texians and a group of colored fellows from the Chattanooga schools. They’ll do good work for you. But I understand you’re here to take a gander at another fine piece of machinery, isn’t that right?” He did not lower his voice or treat the subject with any specific gravity, and this was no doubt for the best – given that they conversed in public, with dozens of passengers fresh off the street rails milling to and fro.

Cly replied in kind, “That’s the plan.” And then he made the rounds of introductions, following which, Normal Somers urged them to follow him to a service lot beyond the edge of the cemetery.

“Lots of folks park their buggies and carriages and whatnot, then ride the street rail into town. This here lot,” he said with a sweep of his arm, “is watched by Charlie over there.” His sweeping gesture ended in a wave at a tiny old negro with at least half a dozen firearms in his immediately visible possession, probably more. “Charlie keeps an eye on things, and if you come back to your ride and it’s in one piece, you tip him whatever you’ve got handy. That’s our buggy – if you want to pile inside, I’ll go settle up.”

The buggy in question did not come attached to a horse. It had a front-mounted motor that drew a big wheeled contraption that looked cobbled together from a rolling-crawler, a cabriolet, a street rail car, and perhaps a two-man flier. It was a hodgepodge piece of machinery, but it was big enough to take everyone wherever they felt like going, and the stretched-wool surrey top kept the worst of the sun off their heads.

Kirby Troost again sat beside the captain, and leaned over to mumble, “I was going to complain that this was a conspicuous sort of ride, but looking around at the lot, I am forced to revise my opinion.”

It was true. All the vehicles in Charlie’s lot were similarly patchworked and rigged together. It could not be said that they were all of a single type, except that none of them had started out looking like they did at present. The captain detected the occasional small dirigible chassis, boat motor, carriage frame, and dual V-twin engine protruding from a hood … but most of what he spied was made of unidentifiable bits.

The captain said, “I suppose people out here like to improvise.”

Ruthie replied, “They do it because they must. Many of these—” She cocked a thumb at the next row of buggies. “—are made with things the machine shops throw away.”

“I believe it,” Troost said. “The whole yard looks like a big science experiment.”

Shortly, Norman Somers returned and climbed up onto the driver’s seat. He pulled a lever, which produced a large black umbrella, and with a popping sound it opened to shade him from the sun so that he was protected as well as his passengers. “All right!” he declared. “Now we can get on our way. And how was your trip from the city?” he asked over his shoulder.

“Just fine,” said Cly, who was still a bit surprised by how unstealthy this whole production felt. “And might I ask, where exactly will the rest of our trip see us heading?”

“The rest of your trip?” He gave a narrow chain a hearty yank, and the engine burbled to life, spewing fumes and soft puffy smoke clouds in every direction. Over the diesel rumble he said, “We’re going to take a stroll around a lake, that’s all we’re goin’ do. Maybe we swing by the bayou’s edge and visit with some of the fellas we find there, huh? This your first time in New Orleans?”

Cly said, “Mine and Fang’s? No. Huey, yes. Troost?”

“I never been here before,” the engineer informed them. “Been around the Gulf a bit. Visited Galveston once, and Houston. Spent some time in Mobile. Somehow, never managed to land myself right here on the delta. Not till now.”

“Then, let me welcome you to my home city, and I hope you enjoy your stay.”

The rest of the way was filled with jovial chitchat of a similar nature, and gradually the tall grasses, half-paved roads, and spotty marshes gave way to more fully untamed wet, thick grasslands and roads that were not paved at all. The rumbling buggy drove them bumpily along the rutted dirt paths and beneath gigantic trees that oozed lacy gray curls of Spanish moss and peeling spirals of bark and vines. Though the day was young, the world became darker as they moved farther from the city’s hub; before long, the paths were so overgrown that the long elbows of cypress trees met above them, and the whole road was cast in shadow. Whereas before, they could hear the guttural hums of other buggies and the clattering buzz of the street rail cars moving back and forth between their stops, now the passengers heard nothing but the rollicking grumble of their own engine. And behind it, in shrieks and whispers, they picked up the calls of birds and the croaks of a million frogs, plus the zipping drone of clear-winged insects the size of bats.

Off to the side of the road, among the trees, the land grew less landlike and more swamplike.

“Where the hell are we?” wondered Kirby Troost aloud.

Norman Somers somehow overheard him, and he replied, “Over there, to the right, see? That’s the Bayou Piquant.”

“Where’s the lake?” Troost asked, louder than he needed to, given the superior quality of Mr. Somers’s hearing.

“On the other side of the bayou. No worries, my friends! I get you to Pontchartrain just fine, okay? We’ll be there soon.”

True to his word, Norman pulled off to the side of the road on the far side of what could reasonably be proclaimed a swamp. He dismounted from his seat and said, “One moment, fellas.” And Ruthie did her best not to look put out at being lumped in with the lads.

Somers disappeared behind a buttonbush slightly taller than himself. Sounds of rustling, heaving, shoving, scraping, and finally the steady tick-ticknoise of a chain cranking clattered out from the spot where he’d vanished. He did not immediately emerge again, but a definite shift occurred – some strange motion that at first made so little sense that Cly and his crew members couldn’t be sure what they were seeing.

But as the seconds clicked by and the chain pattered on, seams appeared in the landscape.

What had seemed at first to be a pair of colossal bald cypress trees were lifted, and as if mounted on a track, they slid to the left, taking a significant chunk of the landscape with them. The buttonbush and two smaller members of the same species went jerkily scooting away as well, and the whole scene slipped as easily and thoroughly as the dropcloth background of a play – revealing a pair of large mirrors that served as the juncture of three unnatural lines. Their angles made the trunks, mosses, twigs, and vines repeat indefinitely, creating the perfect illusion of infinite swamp-space as long as they were touching.

Fang let out a low, impressed whistle.

Houjin’s mouth hung open.

Kirby Troost adjusted his hat and sniffed as if he encountered this kind of thing every day.

Ruthie gave a small, smug smile.

And Captain Cly said, “I’ll be damned.”

Ruthie asked in French, “You’ve never seen anything like it, have you?”

“Non,”replied Cly. “Jamais.”

If she was surprised to hear him reply in kind, she did not give him the satisfaction of showing it. Instead she said, in English this time, “Anderson Worth designed it. He grinds glass lenses for spectacles, and he says that mirrors are not so different, the way they change the light – and the things we see.”

Houjin found his voice and asked, “Where’s Mr. Worth now?” “Is he still here? I’d like to talk to him. I want to know how he made this!”

“You will meet him at the camp.”

Before any more questions could be generated, Norman emerged from behind a water oak with a mile-wide smile on his face and said, “This is something else, bien sûr?”

“It surely is, Mr. Somers!” Houjin exclaimed. “Can I come down there and look at it?”

“Right now? No, but maybe later if you want, okay? For now, we got to get out of the road and close this gate back up again.” With that, he climbed back onto the buggy’s driving seat and restarted the engine with a yank of its chain. “We can’t go leaving the way open for anyone to come inside. It keeps out the riffraff, because this is one of only two ways through the swamp to the camp.”

“What’s the other way?” Cly asked.

Ruthie answered. “You’ll find out later.”

Norman drove the machine past a certain line, deeper into the swamp than it felt the wheels could possibly turn, given the terrain … and he dismounted again, landing with a splash in a soupy mess that was not half so deep as it looked. He skipped back to a set of controls, large cranks and a locking lever, and as he moved, he walked on water.

“Another illusion?” Cly asked Ruthie.

She said, “Oui.”

And when Somers returned, still smiling that toothsome grin, he said, “What we do, you see – is we drop down stones into the bayou, and then we build a road on top of them.”

“What do you use to make it?” Houjin asked.

“Oak boards, mostly. We paint them black, and just like that—” He snapped his fingers. “—they disappear, and for all anyone can tell, the bayou is as deep as the ocean. ’Cept for the cypress knees. Those don’t lie, but they fib.”

Another mile through what looked like open swamp – without any roads, without any signs, and without any hint of a path – and the way opened to something like a clearing, though it was not very well cleared.

It might have been better described as a settlement, for such it was, and a well-considered settlement at that.

Tree houses were lifted up above the soft, easily flooding ground. They were mounted six to eight feet up the trunks, and accessible with ladders; they were roofed with native flora and insulated with thick bundles of dried moss, so that when viewed from above, they would not rouse suspicion. Let the dirigibles scope and soar. Nothing at the bayou camp would give any scout a cause for alarm.

Large canopies, woven from palmetto leaves and carefully camouflaged, were strung up on willow poles in order to hide two rolling-crawlers either bought or stolen from the Texians. Another canopy covered boxes of munitions and supplies, which were stashed upon a platform that was raised off the bayou floor much like the houses – and yet a third canopy clearly functioned as a meeting place, and possibly a dining hall.

There beneath the verdant overhangs both natural and man-made, the swamp was a green-black place of beauty and shadow. It was a place of precision and caution, activity and consultation.

At a quick, casual count, Cly estimated perhaps two dozen men in the camp, the majority of them dark skinned and wearing Union uniform pieces in much the same way that the Texians wore their own garb – without any attention paid to the official lines of the garments. Everything was adapted to the thick, wet warmth that was trapped there in the swamp. Everything bowed to the dense heat and close-pressing smell of vegetation being soaked in its own rot – of new plants and freshly broken branches, of stringy grass filaments and gray-felt moss, and the leftover whiffs of catfish fried at an earlier meal but long since eaten.