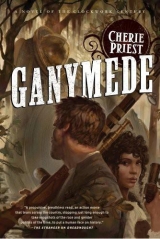

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

As if she’d been waiting for an entrance cue, Ruthie chose this moment to swan back down the stairs and into the lobby, looking no different at all from when she’d left it – apart from a sturdier pair of boots than strictly matched her dress, and a few inconspicuous lumps here and there in the long silk jacket.

“I am back,” she declared. “I have a gun, and I am ready.”

Josephine stood and went to the hall closet. She retrieved a black hooded cloak that was really too warm for the occasion, but she liked having it all the same. “One moment,” she declared. “I need to gather some things as well. Ruthie, since you’re so damn determined to be useful, see if Mr. Crooks wants anything.”

Ruthie turned the full, blinding force of her charm on Gifford, who appeared embarrassed yet again to have been noticed. Everyone in the room knew by now that he was not terribly accustomed to such houses, and there was literally nothing that anyone could do to put him at ease. This didn’t stop Ruthie from giving it a go, as directed.

On her way upstairs, Josephine heard the woman offering water, whiskey, rum, or coffee, and she heard only mumbles from Gifford in return.

It took no time at all for her to grab Little Russia from its spot in her desk; a box of bullets that she dumped into a pouch, which she stashed in the cloak’s inner pocket; a small derringer she sometimes carried as backup; and a wad of emergency cash and assorted coins.

Downstairs she went again. Ruthie was champing at the bit to hit the road – as was Gifford, who couldn’t turn any pinker with a pot of paint. “Ladies,” she said to bid them adieu. “Ruthie, Gifford. When was the last patrol?”

“Right after we got here,” Gifford told her.

“Let’s say five or ten minutes … all right. We’ll go out the back. We’ll have more time if we head toward Rue Barrack.” She tossed her big ring of keys to Marylin and gave Ruthie one last look – on the off chance her resolve was weakening, and maybe she’d change her mind.

No such luck.

“All right, then. Let’s go.”

Out the back door they stepped, into the wet, dark smell of the river that clung to the walls and wafted off the street – held in place by a layer of fog that was forming before their very eyes.

“Ugh,” Ruthie complained. “Just what we need.”

Josephine corrected her, “It isjust what we need. It’ll give us cover as we get out of town.”

“Not if it stays like this,” her determined assistant argued. “It is too thin to hide us, and so thick, it could hide … other things.”

“The zombis are down by the river and the Texians are being useful, just this once. Their patrols will keep the Quarter clear, you can count on that. The dead are too dumb to run and hide. They only want to feed.”

Gifford gazed uncertainly at the wisping fog. “The dead? I’ve heard stories, but … they’re not true, are they?”

“They’re true, Mr. Crooks,” Josephine informed him. “The dead Walk, and they are usually hungry. But they’re no threat to us here, or where we’re going.”

“You said they’re down by the river, and we have to cross it!”

“We’ll cross west of here, away from the Quarter. We’ll be fine.”

Ruthie whispered, “And how do we get to the ferry? It’s too far to walk unless we’ve got all night.”

“The cabs, out on Rue Canal.”

“They will be closed for the night,” she noted, even as she fell in line behind Josephine, with Gifford behind her. To the alley’s edge they went, looking both ways before darting out onto the street.

Over her shoulder, Josephine hissed, “Then we’ll have to wake someone up.”

Night had fully settled now, and the gas lamps made pockets of brightness that lit the corners and crossways. Sticking to the shadows, the three fugitives from the curfew ran on toward Rue Canal at the Quarter’s edge. Upon hitting it, they went left – back toward the Mississippi, down to the river in exactly the way that Josephine had promised they would not. But that’s where the carriages usually waited. They were now folded up for the evening, except for a few stragglers who were allowed to break curfew for the sake of emergency.

These late-night drivers were mostly bored and huddled against the mist, playing cards with one another or drinking surreptitiously from the bottles they kept by their seats. This far edge of the Quarter’s boundary was not so strictly watched, for even the controlling, aggravating Texians understood that this was a commercial border, and strangers to the city might not know the limits. Sometimes, a way must be found inside or out.

Josephine suspected it had more to do with leaving loopholes for Texians to wander off during their leaves, but there was no time to stew about the injustice of it all, not when Rick was hurt and surrounded by pirates.

She dashed up to the first carriage, manifesting under the closest gas lamp like an apparition. The driver gasped. He was an older man, with dark skin as wrinkled as last month’s apples. Pulling himself to his feet, he stepped off the curb and said, “Hey, now, ma’am. It’s after curfew, and here you are sneaking about—”

She cut him off. “What do you care who sneaks where, so long as we can pay? We’ve left the Quarter with Texas’s permission,” she lied outright. “We need a ride, and we have money. Get on your seat and drive us.”

“Now, that’s no way to talk to—”

“If you’re not interested, we’ll just ask one of those other gentlemen over there.”

“Nobody said I wasn’t interested. But you fine … folks,” he said as Gifford and Ruthie emerged from the shadows of the cross street. “You can get an old feller in trouble! We’re not supposed to move nowhere, not without a note from the new man’s office.”

“We have no such note. If you won’t drive us, we’ll try the next man in line.”

Ruthie stepped forward, positioning herself so that her very best angles were lit by the grimy, fog-smeared light. She pushed herself very close into the driver’s space, and he recoiled, but only in a perfunctory manner that was quickly eased by the prostitute’s pretty smile.

“You wear no ring,” she observed.

“No, miss, I … my wife, she done passed on. She’s a long time gone, God rest her soul.”

“Then let me sweeten the deal for you, eh, sugar?” She placed one long-fingered, perfectly manicured hand up against the driver’s head and whispered behind it into his ear. The whispering took longer than Josephine liked, but the look on the man’s face told her that whatever Ruthie was promising, it was working.

“I’ll drive you, I’ll drive you!” he stammered. “That’s a real generous offer, and, and, here.” He hustled to the side of the carriage and opened the door. “Y’all just climb right up inside and I’ll take you where you’re going.” He paused. “Where areyou going?”

Josephine accepted Gifford’s hand and climbed up onto the carriage’s step, stopping only to say, “Get us to the ferry at Tchoupitoulas.”

“Yes, ma’am. Right away, ma’am.”

Gifford crawled in behind her, and both of them settled into an interior that was cramped and dark, but clean. Ruthie poked her head up to the window nearest Josephine and said, “I will ride up front.”

“Good girl, Ruthie.”

Gifford sat forward, asking very close to her ear, “Is she … Is she—?”

“Don’t ask if you don’t want to know, Mr. Crooks.” The carriage took off with a lurch. Their heads nearly knocked together, but they dipped away from each other at the last moment. “We are what we are, and we use the tools at our disposal.”

“But she shouldn’t have to—”

“She choosesto.” And almost brightly she concluded, “Look, we’re moving – and like the wind, I’ll note.”

Gifford Crooks settled back against his seat, his face unreadable in the flickering shadows of the gas lamps in the city as it disappeared behind them. Queasily, he said, “I hope our driver can keep his eyes on the road. Not every man can pay attention to two things at once.”

“True, but I know plenty of women who can – and Ruthie is an excellent horsewoman, should the situation call for it. Don’t worry, Mr. Crooks. Not yet.”

“So I’m allowed to worry later?”

“Allowed? I’ll positively encourage it. We’re headed to a pirate bay that’s under siege. The night will get worse before it gets better.”

They rode the rest of the way in silence, unable to hear anything from the driver’s seat and unwilling to speak until the river, where the lights of the ferry and the sound of its steam-driven paddle wheel were a huge relief, though not huge enough to take away any of Josephine’s simmering terror. At any time, her baby brother could die from his wounds – away from home, away from the bayou, with no family and only the rough ministrations of his fellow guerrillas and unwashed privateers to soothe the pain.

She wouldn’t have it. She’d arrive in time, and she would save him.

She squeezed her gun like a talisman, as if it could help her, or help Deaderick – beyond commanding someone to assist him. There might be someone else present – someone with needles, salves, and tinctures. Pirates came from all walks of life, she knew this from experience. A doctor, disgraced from some terrible malpractice. A field medic, having escaped the war. Some foreigner with the training of a different land.

Anything was possible.

She’d heard that North Africans had good medicine, that the worshippers of Muhammad were well trained in math and surgery. The Chinese, too, were known to be great healers, though their medicine was strange to the Western mind.

Pirates didn’t much care about an officer or medic’s race or God, so long as a fellow could patch a body back into a single piece.

For that matter, Josephine mused as she stumbled down from the cab’s step, she’d settle for a woman. A nurse would do in a pinch, if she could find one. If one were so mad as to surround herself with men like those at Barataria.

At the river’s edge, the glowing pier looked like matchsticks against the flowing expanse of the Mississippi, snaking through the night. The river was awesomely black and sparkling, so wide that the other side was not apparent; so powerful that it moved like the monstrous leviathan of legend, undulating south to join the Gulf. It rustled and rushed, making the usual music of water being pushed and churned by the tens of thousands of tons.

As soon as the carriage stopped, Josephine and Gifford could hear the Gulf, and tried to take comfort from it. “Almost there,” Josephine lied to herself and to him – and though he knew better, he did not correct her.

She threw open the cab’s door before the driver could see to it, and as she jumped down off the stair, she heard Ruthie climbing to the ground on the other side. Ruthie walked around the front, stopping to pat the horse’s sweaty brown head. She rejoined her employer by the time Gifford could extricate himself.

Josephine handed off a few coins, one of which ought to be several days’ wages for the old driver. He thanked her with a mumble, grasped the front of his pants, and tucked in his shirt. He tipped his rumpled cap and wished the lot of them a good night, and he was on his way immediately – leaving the three would-be rescuers standing at the edge of a milling group of other travelers, all of them waiting for the ferry.

The low, flat barge was sidling up to the pier even as they watched. Its engines rumbled with the same sound and the same fuel as the rolling-crawlers, forcing the side wheel to dig deep through the current and haul the thing along. Carriages, horses, and two or three stray messengers and merchants crowded eagerly forward. Sailors on board threw ropes to the workers on the pier, lining up the long, pale boat and cinching it against the launch. Then a wide double ramp was lowered drawbridge-style from a power-driven pulley, allowing the ferry’s late-night guests to disembark.

There weren’t many people on board – not at this hour, coming up close to nine thirty, and not with the curfew dealing a death blow to the nightlife.

Only a few tired-looking travelers led yawning horses off the boat, and behind them came half a dozen Texians. Three were in uniform, three were not; but anyone who’d seen a Texian official knew the posture anywhere. Josephine recognized it as easily as the smell of baking bread. They wore an insouciance and a swagger she found infuriating. They walked as if they had authority, and they did not expect to be asked any questions about it.

Still, she smiled tightly and with civility. Some of them ignored her; one said, “Ma’am,” in passing; and the last one off the boat tipped his hat in her general direction. As this final passenger debarked, a Texian almost too young to wear the uniform went running up to him, saying, “Ranger Korman, there you are. It’s so good to meet you, sir. I’m so glad you could make it.”

Rangers. Hat tip or no, they were the worst of the bunch.

A dockhand made the call for travelers to board with fares in hand. Gifford Crooks led the way, still in his Texian uniform and looking like less trouble than his two companions. Then again, considering that he was accompanied by two ladies of the evening, perhaps he looked like the most trouble anyone had seen all week.

Josephine might have passed for a respectable spinster – someone’s governess or middle-class aunt, hidden under her cloak – and she might have even passed for white, for Gifford’s mother, in a pinch. But Ruthie, in her flamboyant garb, darkened eyes, tea-colored skin, and brightened lips, would fool no one on any count.

They scrambled aboard quickly and settled in for the trip, but no one was very settled, except perhaps Ruthie, whose face had firmed into a look of grim, ambitious concentration. Despite her initial vows to the contrary, Josephine was glad Ruthie had insisted on coming along. She even reached out and took the woman’s gloved hand in her own, just to have something to hold that wouldn’t mind being squeezed a bit too hard.

Across from the pair of them, seated on a bench and trying not to slump there, Gifford Crooks worked hard to appear alert and ready for action; but it was easy to see that he’d had a rough afternoon, and he hadn’t intended to go back to Barataria tonight.

The ferry fought the river, foot by foot, and the paddle wheel dragged the lightly laden barge to the west bank. The engines strained and the diesel spewed out over the water, where fish occasionally slapped against the surface and floating logs rolled over as lazy and large as the alligators that hung closer to the marshes – outside the current’s pull, where the water was stagnant and smelly.

Behind them, the French Quarter drifted away. Its gas lamps struggled against the darkness, signaling the stars and mimicking the moon. But the fog had rolled in hard, and it blanketed the blocks with its warm coverage and left the curfew-quieted neighborhood a low, gray smear against the waterline.

Finally the ferry pulled up against the western pier, and another crane lowered another drawbridge down against the deck. The passengers disembarked into near emptiness.

Josephine shivered despite herself, and despite her too-warm cloak. “Now comes the hard part,” she breathed.

“Pourquoi?”

Gifford Crooks answered Ruthie as they walked away from the water, back toward the docks and the small shipping district that springs up around any ferry’s destination. “Now we have to cross the marshes. Now we have to get to the island.”

Ruthie nodded. “Then, on y va! Before it gets any later.”

Josephine asked, “You’ve never been to Barataria before, have you?”

“How do you know?”

“If you’d ever been, you’d understand why the rest of the trip is a problem. Gifford?”

“Yes, ma’am?”

“Where’s our boat?”

“A mile from here down the river road, on the edge of the canal,” he said quietly.

She asked, “Are you sure?”

“No, but that’s where we’ve been leaving the blowers for coming and going – and that’s where I left mine, when I came to town to give you Fletcher’s message. If it’s not there, I don’t know what we’ll do.”

“If it’s not there, we’ll come back and look for something else. Mr. Crooks, do you have a light?”

“I do,” he promised, and he pulled an electric torch from his jacket. It was small, but it’d have to do. The roads up and down the marsh’s edges were not uniformly lit, and they were dangerous.

Now Ruthie’s concern showed through, only a little, leaking past her determined demeanor. “We will walk a mile, in the dark?”

“Mostly in the dark,” Josephine confirmed. “But it shouldn’t be too bad. The Texians are purging the bay, aren’t they? We shouldn’t run into any robbers or mercenaries.”

“Unless they have been chased outof the bay,” Ruthie mused. “Some of them are alive. Deaderick’s still alive.”

Gifford tried to reassure them. “Most of the pirates went out to the Gulf, heading south if they could. There are ships at the coast to take them in – and those who didn’t get that far went deeper into the swamps. There are dozens of islands between the pirate docks and … and anything else. The rest of Louisiana. The river. The ocean.”

“And we have to wade past them.”

“The blower has an engine,” Gifford informed them. “We’ll get through pretty quick, all things considered.”

“I hope it has oars, too,” Josephine said, setting off down the packed-earth stretch leading in the direction Gifford had indicated. “Because we can’t risk the noise. Not once we get past Bay Sansbois.”

The Pinkerton man took a deep breath and said, “Sooner than that, to tell you the truth. We’ll have to take the water straight down to the edge of the islands at Point à la Hache, and then cross our fingers, cut the motor, and slink over to the big shore.”

Ruthie asked, “What about the siege?” and she darted to catch up as Gifford pumped a switch, then flicked it – sparking a filament to create a wobbly yellow beam. The small device hummed in his hands. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a glove, which he wrapped around the torch like an oven mitt. Within twenty minutes, the thing would be too hot to hold.

He took Ruthie’s elbow with his free hand, guiding her to walk beside him. “The siege … I don’t know. They’d done their worst by the time I left ’em, and mostly they were just sweeping the place, blowing up what airships they could reach, and wreaking havoc to wake the devil. If we’re real lucky, they’ll have gotten bored and gone home. They’ve done what they set out to do, haven’t they?”

“It depends on what they were up to. I mean, what they were reallyup to,” Josephine worried aloud. “If all they wanted to do was scare some pirates, or blow Lafitte’s old docks to pieces, I guess they’ve done their duty. Texas can afford to waste the time and ammunition on a bunch of outlaws who’ve been camped there for a hundred years, but why now? Why would this new fellow make it a priority, first thing? The pirates didn’t have anything to do with his predecessor getting eaten.”

Gifford speculated, “Maybe they don’t know that. Maybe they think the bay boys had something to do with it, and they don’t know anything about these … about the dead, down by the river.”

Josephine didn’t respond right away. She walked on Gifford’s left, with Ruthie on his right, and she scanned the narrow strip of road she could see by the light of the electric candle. Eventually she said, “Deaderick was there, and Fletcher Josty. I hate to wonder, but I can’t help it.”

“Wonder what?” he asked.

“Wonder if Texas didn’t follow them down from Pontchartrain. Wonder if Texas is killing two birds with one stone, uprooting the Lafittes and going after the Ganymedein one big push. Ganymedeisn’t at Barataria, but Texas doesn’t know that.”

And then all of them were silent, all the way down to the canal.

Six

North Texas was as good a place to stop as any, and on the edge of Oneida was a temporary hydrogen dock – the kind that was scarcely temporary anymore, and had become a small town of its own, hanging on to the settlement’s edge like a barnacle … a barnacle that might explode and take half the desert with it, given just the right sort of accident. Bigger cities had bigger, better regulated docks; but on the unincorporated frontier, these mobile constructions squatted wherever they found a place to do so. Dangerous, dirty, and marginally managed by whoever was richest and had the biggest guns, the docks were not popular with travelers or merchants, but they were necessary. And heaven knew the air pirates were happy to make use of them.

All across the Panhandle, the flat, brown earth was speckled with tufts of dark grass, cactus nubs, and tumbleweeds being kicked about by the occasional dust devil. It was a dry, dull, featureless place in Cly’s opinion, but he didn’t have to live there, so he didn’t feel moved to complain about it.

As the Naamah Darlingarrived, the whole settlement – hydrogen barnacle and all – was digging out from underneath a windstorm that had knocked down horses, sent water troughs rolling through the streets, and picked roofs off buildings only to fling them miles out into the empty, prickly nothing beyond the town’s grid.

Pale yellow sand the color of sun-bleached leather drifted into piles in the corners of fences and up against the warped wood walls of the church, bar, saddle company, law office, laundry, jail, dry goods store, and clapboard train station with its lonely pair of tracks. Men were already setting upon the tracks and sweeping them, and from the drifts of bone-dry dirt, the occasional flap of canvas would disturb the seamless layer of brown.

Dirigibles large and small were tangled together on the dock’s eastern edge, implying a western zephyr that had moved with the might of a bored god’s fist. Riggers and engineers swarmed around these docks, shouting to cooperate and untangle the lobster claws and lines, and to dig out the pipes themselves to determine what had been uprooted, and what had only been bent out of place.

But the western line of the dock was nearly unoccupied, save for two small mail express dirigibles that had been battened down with better rigging. Cly set his own bird down beside them, and ten minutes later he was on his way to town.

Fang and Kirby Troost remained with the ship to see if the sulfuric acid vats were stable and could be hooked up to the hydrogen hoses, and if not, to assist with repairs. But Houjin accompanied the captain, ostensibly to get a gander at Oneida. Houjin was seventeen, and nothing short of brilliant. But he’d spent most of his life sheltered under the Seattle streets. Any chance to get out of the city was a chance for him to learn, observe, and drive people crazy.

“This place is a wreck!” the kid declared. “Is it always like this?”

“No, they’ve had a storm,” the captain told him again. The subject had already come up while they were overhead, surveying the damage in advance of landing.

“But everything is so dry!”

“That’s why they call them windstorms. Or … dust storms. But they’re common out here. No trees, you see. No grass, no plants with roots to hold on to the soil. No mountains to break up the sky and give the weather something to work around.”

“It’s hot as hell.”

A straggling gust of warm, dusty air smacked them in the face and dragged itself past them, tugging at their clothes and coiling off into tiny dust devils behind them. The captain pulled his goggles down off his head and fixed them over his eyes to keep out the next batch of blown debris, and he said, “You think this is hot? Wait until we get to the Gulf.”

“It’s even worse?”

“It’s just as bad. It’s wet, and the river runs through it – so there aren’t just trees but swamps, and grasses that grow out of the water as tall as me. Moss hangs off every branch of every tree, and everything is green and overgrown. Everything lives there. Giant trees that look like they’re melting. Animals like you’ve only heard about in books.” An almost wistful look crossed his face, but he put it down quickly by recalling, “You’ll sweat through everything you’re wearing. It’s like you never dry off, not really.”

The boy’s enthusiasm flagged, but quickly buoyed back up again. “Can we swim in the river? That’d be a good way to cool off.”

“I wouldn’t recommend it, not unless you want to get bitten by snakes, or eaten by alligators.”

“Hm,” Houjin said, chewing this over as they strolled past a dog crawling out from under a saloon’s porch. The animal sneezed and shook itself, then wandered away. “And you used to live there?”

“I didn’t … I didn’t livethere. Not exactly. I just spent a lot of time there.”

“Why?”

“You sure are full of questions today.”

“Kirby says I’m always full of questions.”

“Kirby’s right.”

“Where are we going?”

“Over there. Train station.”

“Why? We don’t need a train.”

“No,” the captain agreed. “But we need a telegraph operator, and that’s where towns usually keep them.”

“Why?”

“Because the people who run the trains need to know who’s coming and going. And they need to know the weather and all,” he said vaguely. “And passengers do, too. They like to send notes to their friends and families, if they’re traveling a real long way. Remember how Nurse Lynch was sending dispatches from the road – when she was on her way from Virginia?”

“I remember.”

“Well, there you go.”

“Where are you sending a telegram?”

“To New Orleans – to the lady who wants us to take a job,” Cly said, preemptively answering the next thing poised to fly out of Houjin’s mouth. Speculating on the third thing the kid had on deck, he added, “I tried to drop a wire from Portland, but there was some kind of problem with the poles, they said. And I forgot in Boise, and the office had closed by the time we made it to Denver. Now we’re only a thousand miles out, and I’ve dillydallied about letting the lady know we’re coming. So I’m doing it now.”

“Oh.”

Andan Cly had bought himself a few yards of silence, enough to reach the wood plank walkway of the train station, and to hike the last few feet to the sign that announced WESTERN UNION. He ducked the sign but still managed to clip it with the edge of his head, sending it swinging on its chains. Upon entering the small office, he swiped his goggles off his face and let them hang around his neck.

“Hello,” greeted a tiny, chipper woman with enough highly coiffed black hair to weave a blanket. It was difficult to escape the impression that she’d chosen the style with the specific intent of appearing larger. “What can I do for you, sir?”

Houjin slipped into the office behind the captain, and the woman gave him a puzzled look, but didn’t address him.

“I need to send a telegram. To a … boarding house. In New Orleans.”

“Very good, sir. Our rates are as posted.” She pointed at a sign that noted the charge by the line.

He said, “That’s fine.” He withdrew a square of scratch paper from his back pocket and unfolded it to reveal a message, addressed to Josephine Early at the Garden Court Boarding House on the Rue Dumaine. It had been distilled down to its essence, with all the important parts preserved, but not a drop of sentiment to be detected.

WILL TAKE THE JOB. INCOMING APPROX. APRIL 16. STOPPING AT BB FIRST, THEN INTO TOWN TO TEXIAN DOCK/MACHINE WORKS. SEE YOU THEN. AC.

The operator examined the message and flipped through her listings of New Orleans connections, then hesitated. “Can I ask you something – is ‘BB’ short for Barataria Bay?”

Cly replied, “Sure, that’s where I’m going first. Got to pick up a few things.”

“Ooh,” she exclaimed. And in a low, conspiratorial tone, she added, “I suppose I ought to pass along a little warning to you, then, in the spirit of friendliness.” The operator leaned forward and crossed her arms, the veritable picture of a woman who was thrilled by the opportunity to gossip with a real live person, and not a faceless set of dots and dashes over the taps. “You know how Texas occupies the city, don’t you?”

Cly nodded. “Sure, I know.”

She lowered her voice even further, as if anyone but Houjin were within overhearing range. “All right, then. Something happened to a couple of officers down there – something that no one wants to talk about. They disappeared or died, that’s my guess. Anyhow,” she continued, “a newofficer went in to replace the colonel a couple of days ago. And the first thing he does when he takes post … oh, Lordy. Just guess!”

“I’m a terrible guesser. Just tell me.”

“Well!” she went on, downright breathless. “First thing he does is, he comes down on the bay with a full brigade of soldiers, and they wipe Barataria clean off the earth!”

Stunned, the captain exclaimed, “You can’t be serious!”

She settled back and leaned in her chair. “I don’t know how bad the damage is, ’cause I ain’t seen it in person, you know. But it’s all anyone’s been talking about on the lines. And if you don’t mind my bringing it up, a lot of the men like yourself who are passing through … they’re the kind to stop by the bay, if they’re headed that far south.”

“I don’t mind,” he all but mumbled, but not because her observation bothered him. He pressed for more. “But surely the bay’s not … I mean, it wasn’t destroyed? It’s been … what it is … for seventy years or more. It’s practically an institution! And Texas hadn’t bothered it yet, occupation or none.” The great pirate Jean Lafitte had established the bay as his own personal kingdom, back in 1810 or thereabouts. It’d come and gone, changed hands, changed allegiances, and changed flags with the rest of Louisiana … but it’d always been held by pirates. Lafitte’s sons, after he’d died. And after them, his grandchildren.

She sighed heavily and shook her head with great drama. “I’m sure I couldn’t say, sir. All I know is that the new man made it his mission to stomp the place flat, and he got his plan under way just the other night. I don’t know if there’s anything left standing but the fort, and I’m none too sure about that.”

“Captain?” Houjin started to ask something, but Cly waved him into silence.

“Now, how much of what you’re telling me is gossip, and how much do you know for sure?” he asked the small woman with the big hair.

“I told you, I haven’t seen it myself. But I’ve heard the story from more than one tapper along the lines, so there’s sometruth to it. You’d best be careful, if you’re thinking of docking down that way. Or skip it altogether, that’s my advice.”