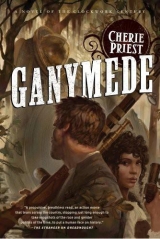

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“I do, almost,” Mumler argued. “And I know the electrics even better than you, I bet.”

“Then you come, too, if you’re willing. The pair of us, me and you – and these fellows. We’ll get it down the river. Norman can take over your pole boat, can’t he? Norman?”

“I can take it, Rick.”

“Good. Take Wally’s pole-craft, and you,” he said to Mumler, “get inside. Come on, if you’re coming.”

Wallace looked at Ganymede,and looked at his leader. “All right, then. Me and you.”

“Go in, get in. You’ll need less help than I will, with me in this shape. Not that it’s as bad as you think,” he added before Mumler could protest any further.

Cly came last. He leaned, stepped off the raft, and stuck to the side of Ganymede,hanging there. Before he climbed in, he looked over at the few assembled men who weren’t on lookout duty, and said, “We’re counting on you fellows, you know that, right? We can’t make this work without you. We’ll drown down here, if you don’t keep us moving.”

Rucker Little, now essentially in charge along with Chester Fishwick, nodded from the bank. “We’re coming. We won’t let you scuttle her by accident, we can promise you that. You do your job; we’ll do ours.”

Cly gave them a nod and a small parting salute as he flipped his leg over the hatch’s round entrance and disappeared down inside it.

He drew the lid shut behind him, settling it as tightly as he could against the seal, then drawing the wheel hard to the right to compress that seal, and lock them all dry inside. As he did so, he felt a strange vacuum settle and he recognized it – he knew it from years of gas masks sucking themselves into position against his face, and from the layers of filters and seals that preserved Seattle’s underground. He knew the feel of it, but here, somehow, it felt more sinister.

In the underground, up above there was only a street – only a city filled with poison air. But that poison air could be cleaned. No one would drown in the street. All it took was a mask to make the city navigable, never mind the rotters and the blinding clots of fog.

But not here.

Not in the water, where once the ship had been lowered, there was nothing above, nothing outside, nothing touching it but the suffocating weight of liquid.

In the previous days, it’d only been practice – only puttering around the lake and learning the controls. This was different. This was the Great Muddy, Old Man River. This was bigger, or at least longer. And maybe deeper, for all Cly knew. Definitely stronger, moving with its unrelenting current from somewhere up North to somewhere beyond the delta, meeting the ocean west of Florida.

He ducked down into the main body of the interior, where red, orange, and small gold lights flickered, brightening the interior, but not much. The dimness was necessary, for two reasons.

First, no one wanted any other craft to take notice of an odd glowing presence beneath the murky waves. And second, if the interior was too bright, the windows would be useless. It was very dark beyond the six-inch-thick glass, but with a small row of encouraging sunset-colored lights mounted externally beneath the watershield – beaming like a tentative smile – it was possible to spy the largest obstacles without being spotted from above.

They hoped.

They’d tested it out after dark on Pontchartrain, but the results had been inconclusive. The ship’s visibility depended on too many things – how many other craft were present, what other lights were bouncing, reflecting, shimmering on the surface. They all quietly prayed, or wished, or crossed their fingers inside their pockets … taking it on fervent faith that the small fleet of pontoons, airboats, and skiffs above could hide them.

“How’s it looking?” Cly asked, taking a sweeping assessment of the room.

Fang signed with one hand: All ready.

Deaderick Early was standing by the window, looking out into the swirling mud and dark, dirty water. Without turning around, he said, “We’re as ready as we’ll ever be.”

Cly said, “Then everyone needs to buckle down, if you can. We’re pushing out into the water, and we don’t know how hard the current’s going to take us. Early? I might recommend that you take a seat there at the window, so you can still serve as underwater lookout. We’re running low on chairs at the moment, but you’ve got handholds there.”

Wallace Mumler sighed. “Just one more thing we’d like to improve in future models. We don’t need for it to be a luxury steamship in here, or anything like that. But it’d be nice to have extra sitting room for the occasional passenger.”

Deaderick said, “Agreed, but for now, we’ll work with what we’ve got. Wally, make yourself at home by the low right port, will you?”

“Already on it, sir.”

A series of taps on Ganymede’s dome sent the message that the folks up top were ready to serve as guides, this crew of Charon’s helpmates, paddling, pulling, tapping, and running small diesel motors that sounded awfully loud, but weren’t, in the grand scheme of the river’s mumblings. Up above, Cly could hear them starting, one by one. The low putter of the motors and the screw propellers from the two or three antique steam engines designed in miniature … these noises filtered inside, and in the submarine’s belly it all echoed, muted and muffled.

“Turn down the lights as far as you can – but not so far that they won’t do us any good,” the captain ordered. Houjin went to one concave wall and threw one set of switches; Wallace Mumler reached up and grabbed the other set. With the flickering fizz of electrics dimming, the interior dropped to a low, golden glow.

The men in their chairs were shapes and shadows, man-sized cutouts of utter black in the charcoal gray of this scene, offset against the wide, bulbous windows that gazed out into the darkness of the river’s underside. But from under the window, the smiling lights glowed, struggling hard against the silt to provide some guide, some illumination.

Morse code taps bounced down from above.

“They can see the lights,” Deaderick said.

“Yeah, I heard it,” Cly acknowledged. “But we’re not all the way under yet. We’ll shove off and get some depth, and maybe they won’t be quite so clear. That’s what I’m hoping, anyway.”

More taps. A quickly sent word of readiness.

Cly took his own seat and strapped himself down. “Engines up, Fang – don’t burn the bottom propeller; we’re still right up against the shore and I don’t want to screw us into the bank. Use the side thrusters above the charge bays. All we need is a nudge.”

Fang nodded, and his fingers flew across the levers with their knobs and buttons so faintly alight that they could barely be described as such. A hum rose up, accompanied by a curtain of bubbles that brushed by the edges of the huge forward windows.

“They aren’t synched,” Cly reminded him. The side thrusters were made to steer, not propel. There was no mechanism to make them fire in time with one another.

Fang didn’t nod this time. He didn’t need to. He needed only to lean his wrists forward, perfectly in tandem, and with a tiny lurch, Ganymedepulled itself away from the bank, away from the sunken winch, and away from the improvised dock at New Sarpy.

Slowly at first, the ship crawled forward. Then, as soon as the riverbed had dropped away before them, Cly positioned his feet on the depth pump pedals and began the nerve-racking work of letting the craft drop, inch by inch, deeper into the river. At the top of the wide forward windows, a small seam of water sloshed outside, at the level where the craft’s crown hit surface. This jiggling seam of inky water crept higher and higher, until it was gone.

And at last Ganymededropped below the waves with one gigantic slurp.

They were in the river. There was no air except what they had in the compartment, and what would be pumped down every so often to cycle what they breathed.

It made Cly’s skin crawl, and Kirby Troost’s, too – the captain could see it when he glanced over at the engineer. Troost looked queasy. One arm over his stomach. One hand over the weakly illuminated dial that showed how far down they’d come, and how much farther they could reasonably go.

Houjin, on the other hand, was vibrating with excitement. They’d stationed him at the mirrorscope he’d liked so much upon first encounter; now it was his job to stay there and report what was coming and going whenever it was safe to leave the tube up in the open air. He turned it side to side, a voyeur to adventure, and the metal tube’s joints squeaked despite their fresh greasing.

“What do you see?” Troost asked the boy.

“The other boats – the little ones, the rafts and skimmers. They’re moving into place and coming up behind us. Ooh! Norman sees me looking at him! He’s waving us forward.… He wants us to pull ahead.”

“Is there anything or anyone in front of us?”

“No, sir, and I’ll say so, if I see something.”

“Then here goes,” he breathed, and he engaged the back propeller screws. Slowly he toggled their controls. The hum of the engines was not quite loud in their ears, but it felt very close all the same. “Everyone hang on. We’re headed into the current.”

He gritted his teeth, not knowing what to expect. It might be easy as a cloudless day, or it might be bad as a hailstorm.

The ensuing jolt was a little of both.

Ganymedebobbed forward and was caught very quickly in a full-surface tug as the Mississippi River got a grip on the craft and hurled it forward. The ship swayed, forcing everyone to take hold of whatever handles they could find; Houjin’s feet slid out from under him, leaving him hanging by the crook of his elbows from the scope.

But Fang’s expert handling of the thrusters soon had the ship aimed steadily downriver, resisting the left and right yanks of the underwater pathways surging beneath the surface, so that it only twitched back and forth instead of swinging out of control.

“This isn’t like the lake,” Cly complained, wrestling with the foot pedals. “And it ain’t like flying.”

Kirby Troost, now fully green around the gills, said, “Bullshit, sir. It’s the same thing as flying; you just have to find a current and ride it.”

“But the currents are all over the place!” he declared. “And I can’t see a goddamn thing.…”

“Can’t up in the sky, either. Find the flow and hold it.”

“I’m trying, all right?”

Ganymededropped precipitously, and bounced up again. Troost said, “Goddamn,” and clutched at his mouth.

“Hang in there, Kirby. Hang in there, everybody. I’ll find it.” He fought with the controls, watching out the forward windows that told him almost nothing about where they were going, or even what direction he was headed. He could feel the river shoving at his back, so he could assume they were headed east and south, since that was the curve and flow of the Mississippi from where they started. “Troost?”

Ominously, he burped. “East-southeast, sir.”

“Fang, you’re doing great. Keep us from spinning, and I’ll get us level,” he vowed.

Houjin was once more standing upright, and now he was braced that way with his legs locked. “The bayou boys are catching up to us, sir. They lost us for a minute. We caught a drag,” he said, using the slang he’d picked up overnight. “Can you slow down any?”

“Nope.”

“Can you … I keep losing the view,” he warned. “Every time we dip under. I can’t adjust this thing in time to keep it steady.”

“Not your fault. I’m the one making trouble over here.”

“No,” Deaderick corrected. “It’s the river. She’s fighting you. Fight her back, and hold her off.”

“I’m working on it.”

Andan Cly closed his eyes. Looking out through the window into the swirling, sediment-packed void wasn’t doing him any good, and the dim red lights of the ship’s interior told him only where to put his hands and feet – which he knew already. His hands were primed on the levers. His feet were propped against the pedals that would expel water or draw it into the tanks, changing the underwater “altitude.”

Or whatever it was called, there below the waves.

For half a minute he was breathless, considering and reconsidering how absurd this situation was – how impossible, and how bizarre it had become. But in the next half minute, he calmed as he sat there, holding fast to the instruments and feeling the water moving around Ganymede—pulling and pushing, urging and demanding, crushing and jostling – and some deep instinct told him not to worry.

It’s only water,he told himself. Only a storm. As above, so below.

He let instinct move his arms and guide his feet, and he told himself it was only the thrusting power of a hurricane – water below, moving no differently from the air above. It wasn’t quite true: the tug was different; the force was different. The weight of the craft was different, too, and it handled more slowly, more heavily.

But it handled. It worked. And soon the craft was stable.

Cly opened his eyes and gazed out through that near-useless window, and saw that Deaderick was standing now, blocking part of the view by looking out into the shimmering, brown-black panorama. In silence, the whole crew stared as the whirling waters went streaking ahead in curls and coils. Fish pirouetted past, their gleaming silver and gray bodies standing out like a flicker of gas lamps as seen from above a city. River-borne driftwood crashed along, smacking the metal exterior, cracking against the window, and spiraling away.

They were within the abyss, and it carried them.

But it did not dash them to bits like the driftwood, or hurl them beyond their abilities.

Houjin whispered, as the moment called for whispering. “Captain, Norman Somers and Rucker Little are caught up, and the other craft are fanning out. They’re giving us the signal. They’re telling us to go forward.”

“Forward. Sure. Here we go. Hey, Mumler, refresh my memory – what’s our first refueling stop?”

“We’re stopping at Jackson Avenue, near the Quarter, but not right on top of it. There’s a ferry stop where we’ve got enough friends to be left alone and we can still dock without any problems. We’d pick up Josephine closer to home, except we don’t want to run into any of the zombis.”

“Zombis?” Houjin asked, peeking his head around the side of the visor.

“I’ll fill you in later,” Cly promised him. “All right, let’s go. We know the general course, but not the particulars. Mumler, you’re on point. Stick with Kirby; he’s got the instruments to tell us where we are, and you’ve got the know-how to tell us where to go. Me and Fang will keep this thing as steady as we can. Huey, you’re our eyes above the water. Tell me if we get out of range, or if we outpace our escorts. And someone’s gotta listen for their taps. Kirby?”

“I’ll keep my ears peeled for ’em,” he said. Troost was the fastest and best at understanding Morse, so it became his job to listen – in addition to the rest of his duties. If indeed he could listen as he wrestled with his digestive situation.

“Good man, Troost. And good on you, keeping everything inside. You’ll get your sea legs soon enough. Mumler, what about our air supply? How are we looking?”

“Fine for now,” Wallace told him. “We won’t need to worry about circulating it for another half hour.”

“Somebody keep an eye on a clock.”

Mumler said, “That’ll be me. I’ve got my dad’s watch. It’s as precise as any nautical piece.”

“It’d better be. By the time we know we have a problem, it’ll be too late – that’s what Rucker said.”

“And he’s right. But we could go closer to an hour without having to worry about it.”

“Glad to hear it,” the captain said. He flinched as a submerged tree trunk careened toward the window, hit it, and ricocheted away. “Jesus.”

“The window will hold,” promised Mumler. “Don’t worry about that. Just keep us moving.”

Cly urged the pedals in accordance with the flow, his hands on the levers to manage their rise and fall; Fang worked the other set of controls, the ones that moved the ship from side to side. Between them, Ganymede’s trip downriver was not smooth or even graceful, but it was steady, and they neither sank too far nor rose too high.

Out of the corner of Cly’s eye, he watched his engineer go green around the gills, and prayed the man wouldn’t vomit … even as he was forced to admit that the submarine was giving them one hell of a wild ride. “Troost?” he called.

“Yes … Captain?”

“You still with us over there?”

“Still here, sir. Hey, Mumler, Early – I’ve got an idea for an improvement, for the next model.”

Deaderick asked, “What would that be?”

“Buckets.”

“Huey,” said the captain. “How’s our escort?”

“Sticking with us, sir. Some of them better than others. The little boats with the little motors are doing best, them and the ones with the big fans.”

“Those guys have poles, don’t they?”

“They do, Captain. But in this current, with all this movement … I don’t know. I hope they can keep up.”

Cly said, “When we stop at – what was that, Jackson Street? – to pick up Josephine and whoever she brings along, we can have a quick conference with the topside men and see how they’re doing.”

The Ganymedecontinued half-carried, half-piloted farther down the wide, muddy ribbon of river. Mostly she stayed away from debris, and mostly they stayed satisfactorily submerged, bobbing above the surface only once, and then diving again immediately. No one saw them, though, or if anyone did, no one knew what it was, and no one was alarmed.

Before long – and much sooner than Cly had expected – a loud series of taps on Ganymede’s top announced that the time had come to begin angling for the shore, for the hidden dock at Fort Jackson.

“Make for the north bank,” Mumler said, and he called out some directional specifics.

“I’m on it,” Cly told him. “Fang?”

Fang nodded.

“All right. Here we go. Let’s see how well this thing steers when we’re not quite running with the current, eh?”

As it turned out, Ganymedesteered with no great ease – but she responded sufficiently to allow Cly to bring the craft up against the dock with a lot of swearing, a few faltering attempts, and finally, success that broke only one pier piling and splintered a second one. The whole crew considered it a victory that no one had died and no one onshore had been knocked into the river.

As the men outside tethered the vehicle into position, everyone within exhaled deep breaths and stood. An all-clear sounded above, and Houjin scrambled up the ladder to open the hatch. “Hi!” he announced.

“Hi!” responded Rucker Little. “Everyone all right down there?”

“Everybody’s fine,” Deaderick said in a voice just louder than the one he usually used for speaking. This was not the time to shout.

“How’d it go?” Rucker asked, leaning his head inside past Houjin to take a look around.

Kirby Troost said, “It went. And I’ve got to go, too, just for a minute. Pardon me,” he added, leaving his seat and heading up the ladder. Houjin hopped out of the way, and Rucker retreated to let the engineer exit.

The sounds of retching barely penetrated Ganymede’s hull. The gags and heaves were followed by splashes, and no one complained, because Troost throwing up in the river was better than Troost throwing up while they were all trapped inside a sealed compartment with him.

Deaderick went to the ladder and said up the hatch, “While we’re stopped, we’ll deploy the hose and circulate the air.”

“Damn right we will,” Cly mumbled. “Fang, get on that, will you?”

Fang stepped to the panel console and released a latch to drop the hose. When a lever was cranked, the hose was pushed through a channel in the hull until it breached the surface.

“I see it,” Rucker Little announced. “We’ll get it and stick it up firm. Start the generator, and we’ll let it run.”

“How long will it take?” Cly asked.

“Not long,” Deaderick vowed. “We can process everything inside in about two or three minutes, if everything’s up to full power.”

“Andan?” asked a new voice.

“Josie, that you?”

“It’s me, yes.” Her face appeared in the open hatch hole. “There you are. Is everything running all right? Everyone … everyone doing all right? Other than Troost, I mean. I saw him already.”

“Everyone’s fine. Everything’s fine. What about you, up there?”

“Things have gotten messy out at Barataria, but I think it’ll be good for us. Texas will be distracted, and maybe the Confederacy, too.”

“Barataria?” he seized on the word, without yet mentioning that they’d agreed to cut toward the canals in order to dodge the Confederate forts. He also did not mention that the canals would take them close to the bay, and close to any messiness that might be going on.

“You heard me,” she said. Then she ordered, “Make way.”

“What?”

“Get out of my way, Andan. I’m coming down, and I won’t have you looking up while I’m doing it.”

He almost mumbled something to the effect of, Nothing I ain’t seen before,but he came to his senses before anything escaped his mouth. Instead he got out of the way as commanded, and stood aside while she descended into the cabin.

“My goodness. Rather warm in here, isn’t it?”

“Rather,” he agreed, even though he hadn’t noticed until she’d pointed it out. “What are you doing in here, huh?”

“Riding along. I’m no good to the men up top; they have enough polers and boatmen. I’ll only attract attention that no one wants, so I’m riding down here with you fellows.”

“What I mean is why are you riding along at all? I don’t get it, Josie. Why don’t you stay home where it’s warm and dry and … safe?”

She lifted an eyebrow. “Practically answered your own question, there, didn’t you?” Then she sighed, and said, “I’ve worked entirely too hard these last few months, planning and plotting, and buying every favor I can scare up to get this damn thing out to the admiral. I’m not going to sit someplace warm and dry and safe while the last of the work gets done. I intend to hand this craft over myself, and shake the admiral’s hand when I do so. This was myoperation, Andan. Mine. And I’ll see it through to the finish.”

A million arguments rose in Cly’s mind, but he knew better than to voice any of them. Ignoring all the obvious reasons she ought to stay where she belonged, he said, “All right, then. But you’ll have to fight Rick and Wally for a seat. Seats are few and far between on this bird. I mean, this fish.”

“I know, and I don’t mind.”

“Suit yourself.”

“I always do.”

“I know,” he said almost crossly. “Just stay out of the way. And don’t forget, I’min charge. If you’re in my ship, you follow orders.”

“I gave you this ship. Or I got you into it, at any rate.”

“But you hired me to pilot it, and if I’m the pilot, I’m in command.”

“No one’s arguing with you, dear.”

Houjin was back at the hatch, delivering a blow-by-blow of what was going on up top. “The hose is sticking out next to the scope. It’s pretty quiet, but it’s sucking down the air. Can you feel it over there?” he asked in the general direction of the vehicle’s far right end.

Wallace Mumler wasn’t standing there anymore, so he shrugged. Josephine approached it and waved her hand around the vents beside the unlatched hiding spot where the tube was unspooled. She declared, “I can feel it. It’s blowing just fine. Plenty of air’s coming in, and since the hatch is open, I can assume we don’t need to vent anything.”

Mumler told her, “No, ma’am. The level’s holding fine – and we aren’t moving up or down, so all’s well from that end. Give it another minute or two, and we’ll head back out.”

“Josie, you said something about Barataria. What’s going on over there?” he asked. He had an idea, but he wanted to hear something certain. Had it already begun? Had Hank Shanks launched an offensive so quickly – taken it from rumor to action in the span of a few hours?

“Pirates,” she confirmed his hopes. “A bunch of them, swarming like bees who’ve had a rock thrown at their hive. They’ve mounted a rally, and they’re raising hell. Maybe they can’t take back the whole bay, but they’re bound and determined to reclaim the big island.”

“Glad to hear it!” he said with more enthusiasm than he’d meant to.

“Don’t get too excited on their behalf just yet. Word out in the Quarter says they’ve bitten off more than they can chew.”

He frowned. “Really? You don’t think they can take it back?”

“I don’t have any idea. I know precious little about the bay these days, or the people who inhabit it. Besides, there’s a curfew – hadn’t you heard? The chain of gossip would run a little smoother if the goddamn Texians hadn’t been shutting down the Quarter.” As she said the part about the goddamn Texians,a strange look crossed her face. Like she was reconsidering something, or reevaluating it. But she continued, “The important thing is, it’s good news for us.”

“You think?”

“The Rebs at the forts will almost certainly head out to help Texas, so the way downriver will be clearer than it might have been otherwise. Fewer eyes watching, and even if anyone sees us, it’ll take them half of forever to recall their forces. We’ll be in the middle of the Gulf by the time they can rally any response.”

Cly turned away from her, revisiting his seat at the captain’s chair. “This is all worth knowing, but there’s been a change of plans. We’re stopping at one of the canals. We’re cutting through it down to the…” He trailed off.

Fang shot Cly a look that no one on earth but the captain could’ve read. The look was fleshed out by a smattering of signing. You’d better lie to her.

And until that moment, Cly hadn’t even realized that this had been his plan all along. It was as if he’d been deluding himself so successfully that the truth hadn’t dawned on him until he was confronted with adjusting it. But this hadbeen the plan, hadn’t it? Ever since he’d first heard that the bay had been taken, and that his fellow unlicensed tradesmen were planning to take it back.

Fang didn’t blink, and didn’t look away.

Cly returned his attention to Josephine and said, a bit too brightly, “Anyway, plans are made to be adjusted, aren’t they? We’ll work it out as we get farther downriver. We’ll have to stop in the canal’s general vicinity to top off our air and fuel supply, anyway. From there, we’ll see how it goes.”

“Andan, I don’t like—”

He interrupted before she could go on fretting about protocol. “We’re sitting inside an advanced military machine like nothing the world has ever known. This thing is armored from top to bottom, and it’s armed to start a war, or stop one. This is just a detour. Nothing’s going to slow us down.”

She frowned and gently bit her lower lip, an old habit of hers that Cly had forgotten until he watched her do it again. It made her look younger, or maybe it only reminded him of when they both were young. “If you understood exactly what I’d risked, what I’d compromised to bring this about—”

“It wouldn’t change a thing,” he assured her. “You did such a great job that the rest of this will be smooth sailing. The hard part’s already out of the way.” He approached her and put his hands on her shoulders, forcing her to look up at him.

She did, and she told him, “Maybe you’re right, but we won’t know until it’s over and we’re on board the Valiant. But I hope we get to stand on that deck, so I can turn to you and tell you that you were right all along. Just get us there, Andan. Get this craft to the Gulf. I don’t care what it takes, and we are nottaking the canal.”

“Stop worrying.” He might’ve said more, but Troost came back down the hatch. Shortly behind him came Deaderick Early, moving slowly but resolutely.

Josephine extricated herself from the almost-embrace and went to her brother, about whom she was still allowed to worry. “Rick, you’re not looking well.”

“I’m getting stiff as I heal up, that’s all. You worry too much.”

Cly let out a laugh that sounded like a cough, and changed the subject before she could accuse them of ganging up on her. “Everyone get back to your places. Josephine, find someplace where you can hold on – this thing jumps and dives like an otter. Someone turn off that generator, if we have the air to keep us alert and alive for the next run?”

“All right,” Troost said. He looked less ill, but still not altogether well. He went to the generator switch and turned it off, then pulled the lever to retract the air circulation hose. “Where’s Mumler?” he asked.

“Right here,” Mumler announced himself as he came down the ladder. “Is this everyone?”

“Looks like it,” Cly confirmed.

“Then I’ll close up the hatch and call us ready to set sail. Or set screws, or start charges, or whatever this thing does. Goddamn,” he grunted, as he turned the wheel to seal them all inside. “They’ll need to invent a whole new lingo for boats like this.”

Josephine stood in front of the window beside her brother. She appeared to be transfixed by the scenery, dark, swirling, and largely undecipherable though it was. “I’m sure sailors the world over will be up to the task. Or airmen,” she amended the sentiment, flashing Cly a look of honest gratitude that gave him a pang of guilt.

He already knew that this wasn’t about to go as smoothly as she’d hoped. He didn’t have any intention of telling her while there was still some trouble she could make about it, and he didn’t yet know how Deaderick or Mumler would handle the news that their detour at the canal would be more extensive than expected, so he didn’t say anything about it yet.

For the moment, though, he didn’t have to. He only had to get Ganymedeback into the river and as far as the canal. What he’d told Josephine off the top of his head was correct: It couldn’t go much farther than the canal without needing its air circulated anyway, so it was a good excuse to pull over when the right place was located.

When all was in order once more, the craft shoved off, its propulsion screws churning at the rear, and the ballasting fins and pumps all working in accordance with the hands and feet of Cly and Fang. Troost called out degrees and directions, helping to adjust their course. Mumler kept an eye on his watch, Houjin kept his eyes plastered to the visor scope, and Josephine kept an eye on her brother – who watched his own reflection in the window, since there was little to be seen on the other side of it except for the black vortex of the river at night.