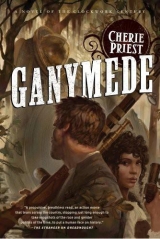

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Cherie Priest

Ganymede

Nor must Uncle Sam’s web feet be forgotten. At all the watery margins they have been present. Not only on the deep sea, the broad bay, and the rapid river, but also up the narrow, muddy bayou, and wherever the ground was a little damp, they have been, and made their tracks.

Abraham Lincoln (From a letter to John Conkling, August 26, 1863)

Dedication

Ganymede is dedicated to everyone who didn’t make it into the history books… but should have.

Disclaimer

Like all my Clockwork Century books, this is a work of fiction. Its facts are contrived and improbable, its finer points are forcibly bent to serve my narrative purposes, and I am led to understand that its zombies are highly unscientific. But if you’re okay with zombies shambling around New Orleans in the nineteenth century … then I’d like to think you can forgive some finessing of politics and geography. So thanks for reading! And please don’t send me letters about how wrong I’ve gotten this whole “history” thing. I assure you, my history is at least as accurate as my portrayal of the living dead.

Acknowledgments

This book would have never come together without the patience, assistance, and all-around awesomeness of the following (in no particular order): Liz Gorinsky – editor, diplomat, and advocate of the highest caliber; my husband, Aric, who keeps the home fires bright; Jennifer Jackson – agent and sounding board, who is worth her weight in diamonds; Bill Schafer, a friend and boss, who invited me on board with love, and saw me off with encouragement; and webmaster Greg Wild-Smith, for preventing personal Internet meltdowns by the score.… A thousand grateful kudos to all of you, for putting up with this Tiny Godzilla.

Thanks also to the community of writers who keep me company as I work from home. The Team Seattle crew of Mark Henry, Caitlin Kittredge (still a member in honorary standing, though she’s moved), Richelle Mead, and Kat Richardson; my convention peeps Scalzi, Mary Robinette, Tobias, Scott, Justine, and many others, who keep this from being such a lonely gig. See also Wil and Warren, Ariana (the gatekeeper), and everyone else in the secret clubhouse that serves the world: I couldn’t do it without you. Likewise, love to the Home Team of Ellen and Suezie, keepers of cats and purveyors of brunches and baked goods.

Mad props also to all the indie bookstores and chains alike across the country. You’ve been so extraordinarily helpful and supportive, and I can’t thank you enough. Particular gratitude goes to the Seattle-area folks who deal with me the most: Duane Wilkins over at the University Book Store, Steve and Vlad over at Third Place Books, and the crew at the Northgate B&N.

And finally, excessive, effusive thanks must go out to all the readers who have embraced this weird little franchise. Thank you steampunks, dieselpunks, clockpunks, steamgoths, and everyone else in the retro-futurist niche of your choosing. Thank you for reading these books, and for sharing them, and for giving them a place on your shelves and in your hearts.

You have made these books happen.

Map

One

“Croggon Hainey sends his regards, but he isn’t up for hire,” Josephine Early declared grimly as she crumpled the telegram in her fist. She flicked the wad of paper into the tiny round wastebin beside her desk and took a deep breath that came out in a hard sigh. “So we’ll have to find another pilot, goddammit.”

“Ma’am, the airyard’s full of pilots,” her assistant, Marylin Quantrill, replied.

She leaned back in her seat and tapped her fingers on the chair’s armrest. “Not pilots like him.”

“Hainey … he’s a colored fellow, isn’t he? One of the Macon Madmen?”

“Yes, and he’s the best flier I know. But I can’t blame him for turning us down. It’s asking a lot, for him to come so far south while he’s still wanted – and we don’t have the money to pay him what he’s worth, much less compensate him for the extra danger.”

Marylin nodded, disappointed but understanding. “It didn’t hurt to ask.”

“No. And if it were me, I wouldn’t take the job either.” Josephine ceased her tapping and shifted her weight, further wedging her voluminous blue dress into the narrow confines of the worn mahogany chair’s rigid arms. “But I sure was hoping he’d say yes. He’s perfect for the job, and perfect doesn’t come along every day. We won’t find anyone half so perfect hanging about the airyard, I can tell you that much. We need a man with excellent flying skills andabsolutely no loyalty to the Republic or the Confederacy. And that, my dear, will be the trouble.”

“Is there anyone else we could ask, anyone farther afield?”

“No one springs to mind,” Josephine murmured.

Marylin pressed on. “It might not matter, anyway. It could be Rucker Little is right, and a pilot won’t have any better luck than a seaman.”

“It’d be hard for anyone, anywhere, to fail so spectacularly as that last batch of sailors.”

“Not allof them drowned.”

“Four out of five isn’t anything to crow about.”

“I suppose not, ma’am.” Marylin lowered her eyes and fiddled with her gloves. She didn’t often wear gloves, given the heat and damp of the delta, but the elbow-length silk pair with tiny pearl buttons had been a gift from a customer, and he’d requested specifically that she wear them tonight. Her hair was done up in a twisted set of plaits and set with an ostrich feather. The yellow dress she wore cost only half what the gloves did, but they complemented each other all the same.

Josephine vowed, “I’ll find someone else, and I’ll show Mr. Mumler that I’m right. They’re going about that machine all wrong, I just know it. All I need is a pilot to prove it.”

“But you have to admit,” the younger woman carefully ventured, “it sounds strange, wanting an airman for a … for whatever it is, there in the lake.”

“Sometimes a strangely shaped problem requires a strangely shaped solution, dear. So here’s what we’ll do for now: Tomorrow afternoon, you take one of the other girls – Hazel or Ruthie, maybe – and you go down to the airyard and keep your eyes open.”

“Open for what?”

“Anyone who isn’t Southern or Texian. Look for foreigners who stand out from the usual crowd – ignore the English and the islanders, we don’t want them. We want people who don’t care about the war, and who aren’t taking sides. Tradesmen, merchants, or pirates.”

“I don’t know about pirates, ma’am. They scare me, I don’t mind saying.”

Josephine said, “Hainey’s a pirate, and I’d trust him enough to employ him. Pirates come in different sorts like everybody else, and I’ll settle for one if I have to. But don’t worry. I wouldn’t ask you to go down to the bay or barter with the Lafittes. If our situation turns out to call for a pirate, I’ll go get one myself.”

“Thank you, ma’am.”

“Let’s consider Barataria a last resort. We aren’t up to needing last resorts. Not yet. The craft is barely in working order, and Chester says it’ll be a few days before it’s dried out enough to try again. When it works, and when we have someone who can consistently operate it without drowning everyone inside it, then we’ll move it. We have to get it to the Gulf, and we’ll have to do it right the first time. We won’t get a second chance.”

“No, ma’am, I don’t expect we will,” Marylin agreed. Then she changed the subject. “Begging your pardon, ma’am – but do you have the time?”

“The time? Oh, yes.” Josephine reached into her front left pocket and retrieved a watch. It was an engineer’s design with a glass cutout in the cover, allowing her to see the hour at a glance. “It’s ten till eight. Don’t worry, your meeting with Mr. Spring has not been compromised – though, knowing him, he’s already waiting downstairs.”

“I think he rather likes me, ma’am.”

“I expect he does. And with that in mind, be careful, Marylin.”

“I’m always careful.”

“You know what I mean.”

She rose from her seat and asked, “Is there anything else?”

“No, darling.”

Therefore, with a quick check of her hair in the mirror by the door, Marylin Quantrill exited the office on the fourth floor of the building known officially as the Garden Court Boarding House for Ladies, and unofficially as “Miss Early’s Place,” home of “Miss Early’s Girlies.”

Josephine did not particularly care for the unofficial designation, but there wasn’t much to be done about it now. A name with a rhyme sticks harder than sun-dried tar.

But quietly, bitterly, Josephine saw no logical reason why a woman in her forties should be referred to with the same address as a toddler, purely because she’d never married. Furthermore, she employed no “girlies.” She took great pains to see to it that her ladies were precisely that: ladies, well informed and well educated. Her ladies could read and write French as well as English, and some of them spoke Spanish, too; they took instruction on manners, sewing, and cooking. They were young women, yes, but they were not frivolous children, and she hoped that they would have skills to support themselves upon leaving the Garden Court Boarding House.

All the Garden Court ladies were free women of color.

It was Josephine’s experience that men liked nothing better than variety, and that no two men shared precisely the same tastes. With that in mind, she’d recruited fourteen women in a spectrum of skin tones, ranging from two very dark Caribbean natives to several lighter mixes like Marylin, who could have nearly passed for white. Josephine herself counted an eighth of her own ancestry from Africa, courtesy of a great-grandmother who’d come to New Orleans aboard a ship called the Adelaide. At thirteen, her grandmother had been bought to serve as a maid, and at fourteen, she’d birthed her first child, Josephine’s mother.

And so forth, and so on.

Josephine was tall and lean, with skin like tea stirred with milk. Her forehead was high and her lips were full, and although she looked her age, she wore all forty-two years with grace. It was true that in her maturity she’d slipped from “beautiful” to merely “pretty,” but she anticipated another ten years before sliding down to the dreaded “handsome.”

She looked again at the watch, and at the wastebin holding the unfortunate telegram, and she wondered what on earth she was going to do now. Major Alcock was expecting a report on her mission’s progress, and Admiral Partridge had made clear that it wasn’t safe to keep the airship carrier Valianttoo close to the delta for very long. Texas wouldn’t tolerate it – they’d chase the big ship back out to sea like a flock of crows harrying an eagle.

She had until the end of May. No longer.

That left not quite four weeks to figure out a number of things which had gone years without having been figured out thus far.

“ Ganymede,” she said under her breath, “I willfind someone to fly you.”

All she needed was a pilot willing to risk his life in a machine that had killed seventeen men to date; brave the Mississippi River as it went past Forts Jackson and Saint Philip and all the attending Rebels and Texians therein; and kindly guide it out into the Gulf of Mexico past half a dozen Confederate warships – all the while knowing the thing could explode, suffocate everyone inside, or sink to the ocean bottom at any moment.

Was it really so much to ask?

The Union thought she was out of her mind, and though they wanted the scuttled craft, they couldn’t see paying yet another seventeen men to die for it. Therefore, any further salvage efforts must come out of Josephine’s own pocket. But her pockets weren’t as deep as the major seemed to think, and the cost of hiring a high-level mercenary for such a mission was well outside her reach.

Even if she knew another pilot half so good as Croggon Hainey, and without any allegiance to the occupying Republicans or the Confederates, a month might not be enough time to fetch him, prepare him, and test him.

She squeezed her watch and popped it open. The gears inside flipped, swayed, and spun.

But on second thought …

She’d told Marylin she didn’t know any other pilots. The lie had slipped off her tongue as if it’d been greased, or as if she’d only forgotten it wasn’t true, but there wassomeone else.

It wasn’t worth thinking about. After all, it’d been years since last she saw him – since she even thought about him. Had he gone back West? Had he married, and raised a family? Would he come if she summoned him? For all she knew, he wasn’t even alive anymore. Not every man – even a man like Andan Cly – survives a pirate’s career.

“He’s probably dead,” Josephine told herself. “Long gone, I’m sure.”

She wasn’t sure.

She looked back at the wastebin, and she realized that with one more telegram, she could likely find out.

Croggon Hainey frequented the Northwest corners, didn’t he? And Cly had come from a wretched, wet backwater of a port called … what was it again? Oh, yes: Seattle—out in the Washington Territory, as far away from New Orleans as a man could get while staying on colonial turf.

“No coincidence, that,” she said to the empty room, realizing she flattered herself to think so. Well, so what? Then she flattered herself. She wasn’t the first.

Downstairs, something fell heavily, or something large was thrown and landed with a muffled thunk.

Josephine’s ears perked, and she briefly forgot about the wastebin, the telegram, and potential news of long-ago lovers from distant hinterlands. She listened hard, hoping to hear nothing more without daring to assume it.

The Garden Court Boarding House was different from many bordellos, but not so different that there were never problems: drunk men, or cruel men who wanted more than they were willing to buy. Josephine did her best to screen out the worst, and she prided herself on both the quality of her ladies and the relative peace of her establishment; even so, it was never far from her mind how quickly things could turn, and how little it would take for the French Quarter to remember that she was only a colored woman, and not necessarily entitled to own things, much less protect them, preserve them, and use them for illicit activities.

It was a line she walked every night, between legitimate businesswoman performing a service for the community of soldiers, sailors, merchants, and planters … and the grandchild of slaves, who could become a slave herself again simply by crossing the wrong state lines.

Louisiana wasn’t safe, not for her or any of her ladies. Maybe not for anybody.

But this was Josephine’s house, and she guarded it with all the ferocity and cunning of a mother fox. So when she heard the noise downstairs, she listened hard, willinginnocent silence to follow, but suspecting the worst and preparing herself accordingly.

In the top left drawer of her battered, antique, secondhand desk, she kept a.44-caliber Schofield – a Smith & Wesson revolver she’d nicknamed “Little Russia.” It was loaded, as always. She retrieved it and pushed the desk drawer shut again.

It was easy to hide the weapon behind her skirts. People don’t expect a left-handed woman, and no one expects to be assaulted by anyone in a fancy gown – which was one more good reason to wear them all the time.

Out past the paneled office door she swept, and down the red-carpeted runner to the end of the hall, where a set of stairs curved down to all three lower levels, flanked by a banister that was polished weekly and gleamed under the skimming touch of Josephine’s hand. The commotion was on the second floor, or so her ears told her as she drew up nearer.

The location was a good thing, insofar as any commotion was ever good. Far better than if it were taking place down in the lobby. It’s bad for business, and bad for covering up trouble, should a cover-up be required. At street level, people could squint and peek past the gossamer curtains, trying to focus on the slivers of light inside and the women who lived within.

At street level, there could be witnesses.

Josephine was getting ahead of herself, and she knew it. She always got ahead of herself, but that’s how she’d stayed alive and in charge this long, so she couldn’t imagine slowing down anytime soon. Instead she held the Schofield with a cool, loose grip. She felt the gun’s weight as a strange, foreign thing against her silk overskirts, where she buried it out of sight. As she’d learned one evening in her misspent youth at the notorious pirate call of Barataria, she need not brandish a gun to fire it. It’d shoot just fine through a petticoat, and knock a hole in a man all the same. It would ruin the skirts, to be certain, but those were trade-offs a woman could make in the name of survival.

Down on the second-floor landing, she stepped off the stairs so swiftly, she seemed to be moving on wings or wheels. She brought herself up short just in time to keep from running into the Texian Fenn Calais.

A big man in his youth, Mr. Calais was now a soft man, with cheeks blushed pink from years of alcohol and a round, friendly face that had become well known to ladies of the Garden Court. Delphine Hoobler was under one of his arms, and Caroline Younger was hooked beneath the other.

“Evening, ma’am!” he said cheerfully. He was always cheerful. Suspiciously so, if you wanted Josephine’s opinion on the matter, but Fenn was so well liked that no one ever did.

With her usual polite formality, she replied, “Good evening to you, Mr. Calais. I see you’re being properly cared for. Is there anything I can get you, or anything further you require?”

Caroline flashed Josephine a serious look and a sharpened eyebrow. This was combined with a quick toss of her head and a laugh. “We’ll keep an eye on him, Miss Josephine,” she said lightly, but the urgent, somber gleam in her eyes didn’t soften.

Josephine understood. She nodded. “Very well, then.” She smiled and stepped aside, letting the three of them pass. When they were gone, she turned her attention to the far end of the corridor. Caroline and Delphine had been luring Fenn Calais away from something.

From someone.

She could guess, even before she saw the window that hadn’t been fully shut, and the swamp-mud scuff of a large man’s shoe across the carpet runner.

With a glance over her shoulder to make sure the Texian was out of hearing range, she called softly, “Deaderick? That’d damned well betterbe you.”

“It’s me,” he whispered back. He leaned out from the stairwell. “That Fenn fellow was passed out on the settee with a drink in his hand. I thought I could sneak past without waking him up, but he sleeps lighter than he looks.”

She exhaled, relieved. She wedged Little Russia into her skirt pocket. “Delphine and Carrie took care of him.”

“Yeah, I saw.” He looked back and forth down the hall. Seeing no one but his sister, he relaxed enough to leave his hiding place.

Deaderick Early was a tall man, and lean like his sister, though darker in complexion. They had only a mother in common, and Deaderick was several shades away from Josephine’s paler skin. His hair was thick and dense, and black as ink. He let it grow into long locks that dangled below his ears.

“You’re lucky it was only Fenn. He’s easily distracted and probably too drunk to recognize you.”

“Still, I didn’t mean to take the chance.”

She sighed and rubbed at her forehead, then leaned back against the wall and eyed him tiredly. “What are you doing here, Rick? You know I don’t like it when you come to town. I worry about you.”

“You don’t worry about me living camped in a swamp?”

“In the swamp you’re armed, and with your men. Here you’re alone, and you’re visible. Anyone could see you, point you out, and have you taken away.” She blinked back the dampness that filled her eyes. “With every chance you take, the odds stack higher against you.”

“That may be, but we need soap, salt, and coffee. For that matter, a little rum would make me a popular man, and we could stand to have a better doctor’s kit,” he added, looking down at an ugly swath of inflamed skin on his arm – caused, no doubt, by the stinging things that buzzed in the bayou. “But also, I came to bring you this.”

From the back pocket of his pants, he produced an envelope that had been sealed and folded in half. “It might help your pilot, if you ever find one.”

“What is it?”

“Schematics from a footlocker at the Pontchartrain base. It’s got Hunley’s writing on it. I think it’s a sketch for the steering mechanism, and part of the propulsion system. Or that’s what Chester and Honeyfolk said, and I’m prepared to take their word for it.”

“Neither one of them needs it?” She slipped the envelope down into her cleavage, past her underwear’s stays.

“They’ve already taken that section apart and put it all back together. It doesn’t hold any secrets for an engineer, but a pilot who wants to know what he’s getting himself into … this might come in handy. Or it might not, if you have to trick someone into taking the job.”

A loud cough of laughter came from upstairs, and the whumpof heavy footsteps. The siblings looked up to the ceiling, as if it could tell them anything; but Josephine said, “Fenn again, heading to the water closet. Listen, we should go outside. Out back it’s quiet, and even if someone sees you, it’ll be too dark for anyone to recognize you.”

“Fine, if that’s what you want.” He pushed the back stairway door open and held it for her, letting her lead the way.

Down they went, her soft, quiet house slippers making no noise at all, and his dirty leather boots trailing a muffled drumbeat in her wake. At the bottom, she unlocked the back door and pushed it. It moaned on its hinges, scraping trash and mud with its bottom edge.

It opened, letting them both outside into the night.

The alley itself was dark and wet, smelling of vomit, urine, and horse manure. Overhead the moon hung low and very white, but they barely noticed it over the grumbling music, swearing sailors, drunken planters, and the late-night calls of newspaper boys trawling for pennies before closing up shop. The gas lamps on Rue des Ursulines gave the whole night a ghostly wash, leaving the shadows sharp and black between the lacy Old World buildings of the Vieux Carré, and leaving Josephine and Deaderick as close to alone as they could expect to find themselves.

Josephine swatted at her brother’s vest pocket, the place where he always kept tobacco and papers. He took the hint, retrieved his pouch, and began to roll two cigarettes between his fingers. “It’s a good thing that dumb bastard let himself be dragged away so easy.”

“Like I said, you were lucky. Some of the younger men lounge around armed, and after a few drinks, they’re quick to draw. Fenn’s not dumb, but he’s harmless. Even if he’d seen you – even if he’d recognized you – we might’ve been able to buy him off.”

“You’d trust some old Texian?”

“That one?” Josephine took the cigarette he offered and waited for him to light it. She gently sucked it to life, and the smell of tobacco wafted up her nose, down her throat. It took the edge off the mulchy odor of the alley. “Maybe. I don’t think he’d make any trouble for us. He’d die of sorrow if we told him he wasn’t welcome anymore.”

Deaderick lit his own cigarette and stepped onto a higher corner of the curb, dodging a rivulet of running gutter water. “You making friends with Republicans now? Next thing I hear, you’ll be cozying up to the Rebs.”

“You shut your mouth,” she whispered hard. “All I’m telling you is that Fenn spends more time at the Court than he does at his own home, assuming he has one. He’s sweet on Delphine and Ruthie in particular, and he won’t go talking if he thinks we’ll keep him from coming back.”

“If you say so.” He sighed and asked quietly, “Any chance you heard from that pilot friend of yours? The man from Georgia – could you talk him into it?”

“He can’t make it, so now I’ve got to find someone else. I’m working on it, all right? I’ve already talked to Marylin, and tomorrow she’ll take Ruthie over to the airyard to look around.”

“There’s nothing but Republicans and Rebs down at the airyard. You’d have better luck in Barataria. Not that I’m suggesting it.”

She snorted, and a puff of smoke coiled out her nostril. “Don’t think I haven’t considered it. But I want to check the straight docks first, all the same. Times are hard all over. We might find foreigners – or maybe Westerners – desperate enough to take the job.”

“How much money you offering?”

“Not enough. But between me and the girls, we might be able to negotiate. There’s always wiggle room. I’ve talked it over with those who can be trusted, and they’re game as me to pool our resources.”

“I don’t want to hear about that,” Deaderick said stiffly.

“I suppose you don’t, but that doesn’t change anything. If we can get this done between us, it’ll all be worth it. Every bit of it, even the unpleasant parts. We’re all making sacrifices, Rick. Don’t act like it’s a walk in the park for you and the boys, because I know it isn’t.”

Life was hard outside the city, in the swamps where the guerrillas lurked, and poached, and picked off Confederates and Texians whenever they could. It was written all over her brother’s flesh, in the insect bites and scrapes of thorns. The story was told in the rips that had been patched and repatched on his homespun pants, and in the linen shirt with its round wood buttons – none of which matched.

But she was proud of him, desperately so. And she was made all the prouder just by looking at him and knowing that they were all struggling, certainly – but her little brother, fully ten years her junior, was in charge of a thirty-man company, and quietly paid by the Union besides. He drew a real salary in Federal silver, every three months like clockwork. Out of sight, at the edge of civilization, he was fighting for them all – for her, for the colored girls at the Garden Court, and for the Union, which would be whole again, one of these days.

And just like her, he was fighting for New Orleans, which deserved better than to have Texas squat upon it with its guns, soldiers, and Confederate allegiance.

Deaderick gazed at his sister over the tiny red coal of his smoldering cigarette. “It can’t go on like this much longer. These … these—” He gestured at the alley’s entrance, where a large Texian machine was gargling, grumbling, and rolling, its lone star insignia visible as it shuddered past, and was gone. “– vermin. I want them out of my city.”

“Most of them want out just as bad.”

“Well, then, that’s one thing we got in common. But I don’t know why you have to run around defending them.”

“Who’s defending them? All I said in behalf of Fenn Calais is that he’s an old whoremonger with no place left to hang his hat. I have a business to run, that’s all – and I don’t get to pick my customers. Besides, the better the brown boys like us, the safer I stay,” she insisted, using the Quarter’s favorite ironic slang for the soldiers who, despite their dun-colored uniforms, were as white as sugar down to the last man. “I can’t have their officers sniffing around, looking too close. Not while I’m courting the admiral, and not while you’re running the bayou. As long as we keep them quiet and happy, they leave us alone.”

“Except for the ones you treat to room and board,” he sniffed. “You let that old fat one get too close. You call him harmless, but maybe he thinks like you do. Maybe he watches you send telegrams, or pass messages to me or Chester. Maybe he sees a scrap of paper in the trash, or overhears us talking some night. Then you’ll sure as hell find out how far you can trust your resident Texian, won’t you?”

It was something she’d privately wondered about sometimes, upon catching a glimpse of Fenn Calais’s familiar form sauntering through the halls with Delphine, Ruthie, or a new girl hanging on his arm … or drinking himself into a charmingly dignified stupor in one of the tower lounges. Occasionally it occurred to her that he could well be a spy, sent to watch her and the ladies. Spies were a fact of life in New Orleans, after all – spies of every breed, background, quality, and style. The Republic of Texas had a few, though as an occupying force, they were all of them spies by default; the Confederacy kept a number on hand, to keep an eye on the Texians who were keeping an eye on things; and even the Union managed to plant a few here and there, keeping an eye on everyone else.

As Josephine would well know. She was on their payroll, too.

She dropped the last of her cigarette before it could burn her fingers, and she crushed its ashes underfoot on street stones that were slippery with humidity and the afternoon’s rain. Her house slippers weren’t made for outdoor excursions of even the briefest sort, and they’d never be the same again – she could sense it. Between her toes she felt the creeping damp of street water and regurgitated bourbon, runny horse droppings strung together with wads of brittle grass, and the warm, unholy squish of God-knew-what, which smelled like grave dirt and death.

“I don’t like it out here,” she said by way of changing the subject. “And I don’t like you being here. Go home, Rick. Go back to the bayou, where you’re safe.”

“It’s been good to see you, too.”

“Just … stay away from the river, will you?”

“I always do.”

“Promise me, please?”

Down by the river and roaming the Quarter’s darker corners, monstrous things waited, and were hungry. Or so the stories went.

“I promise. Even though I’m not afraid of a few dusters.”

“I know you’re not, but I am. I’ve seen them.”

“So have I,” he declared flippantly, which meant he was lying. He’d only heard about them.

“They aren’t dusters,” she muttered.

“Sure they are. Addicts gone feral, like cats. And you worry too much.”

She almost accused him of lying, but decided against starting that particular fight. If anything, it was good that he was ignorant of the dead – or that’s what she told herself. She’d be thrilled if he went his whole life without ever seeing one, even though it meant that he wrote them off as bedtime stories, designed to frighten naughty children.

He last lived in the Quarter ten years ago, before he’d headed off to fight. Back then, there hadn’t been so many of them.