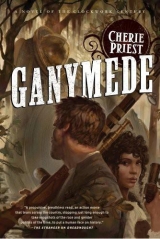

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Shirts were left open, and sleeves were rolled to elbows. But pants were worn down long, sometimes cinched at the ankles or tucked into boots. Cly understood. There were places where a man didn’t dare walk with his ankles unprotected, regardless of the temperature, for fear of stinging insects, snakes, and thorns.

From the corner of his eye, he watched Houjin stick a finger into the mandarin collar of his shirt and wipe away the dampness that collected there. Then the boy swiped at the back of his neck, at the place where his ponytail hung over the collar, and his hand came away wet with perspiration there, too.

The buggy was lured up beneath yet another canopy, which was not otherwise covering anything. It was guided into place by a thickly muscled man with skin that gleamed with humidity and sweat, and hair that grew into a soft black halo. Using both hands, he helped Norman Somers park the machine in the perfect position, where every edge, bumper, corner, and cranny would be covered by the net of manipulated foliage.

“Welcome to camp!” Somers announced. “Everybody be careful getting down, you hear? And stay to the walkways when you can. The earth is half made of mud, my friends. Ruthie, love – you especially. Shall I help you down?”

“Mr. Somers, I am always happy for your assistance,” she said, with a bat of her eyelashes.

When everyone had left the buggy and no one was standing in the mud, the man who’d guided them into the shelter said, “Folks, I’m Rucker Little, and I’m second in command here after Deaderick Early. You,” he said to Cly, “must be the captain Josephine’s been telling me about.”

“Yes, yes, I am,” he said, extending a hand and receiving a shake. “I’d ask how you knew, but Ruthie’s already said that my description is going around.”

“Tall son of a bitch, that’s what Josie told us,” he said. “And this must be the rest of your crew?”

His question called for introductions, and these were made.

By the time the captain had finished, two more men had approached, and these were identified as Chester Fishwick and Honeyfolk Rathburn. Like Rucker Little, they had served in the Union’s colored troops, and they carried themselves like men who’d seen the inside of a military operation.

Once everyone was formally acquainted, Chester Fishwick said, “I can take you to Josephine, if you like. She’s with her brother, in his place. There’s not much room for the whole gang in there, but I expect Rucker would be happy to give the rest of you folks a tour of the camp. When you’re finished speaking with Miss Early, we’ll take you out to the Ganymedeso you can see it for yourself.”

“I’d appreciate that,” Cly said, and seeing that everyone agreed to this arrangement, he followed after Chester, who led him up to one of the tree houses closest to the lake’s edge – though he did not realize how close it was until he’d scaled the ladder. From halfway up it, he could tell that they were in fact quite near to Pontchartrain, no more than fifty yards away from one of its banks.

The ladder creaked beneath Cly’s weight, the willow wood flexing and springing as he climbed from rung to rung behind Chester Fishwick, who scaled the thing swiftly, like a man who did so every day and no longer needed to think about the particulars of hanging on, stepping precisely, or watching his head. At the top, the captain hauled himself over the edge and into a cabin that seemed larger on the inside than the outside would have led him to expect.

Again contrary to its outer appearance, the cabin was not remotely rustic. If anything, it looked like the headquarters of an advanced operation. Texian manuals and tools were shelved and mounted on the walls; a large chalkboard was covered with mathematical formulas and maps; and high-grade military guns were racked beside the door, their ammunition boxed beside them in crates with precise stencils detailing the contents. Mosquito curtains hung from the ceiling, but were tidily bundled above a row of three cots, or draped across the open windows to function as screens.

On the edge of one cot sat a man with wide, strong cheekbones and skin the color of coffee. His hair was long and braided tightly into rows, and his chest and shoulder were swaddled in a bandage fashioned from clean cotton strips.

Beside him on a small camp stool sat Josephine Early, looking not remarkably different from the last time Cly had set eyes upon her. She rose from the camp stool and her brother – for the resemblance was not overwhelming, but decidedly present – shifted his weight as if he’d like to do the same. But she stalled him with a hand upon his unbound shoulder.

Ten years had left her body fuller by perhaps that same number of pounds, as if she’d grown into her age. It looked good on her, Cly thought. And he tried not to think any harder about other things that had looked good on her, in other times.

Now she wore a dress that was out of place among the camp full of men; it was too fancy by at least five dollars, and its fabric was meant to shimmer in a ballroom rather than perch upon a stool. It was easy to see that she still wore whatever she’d arrived in. She’d tucked up the lace on her sleeves and traded her pretty boots for a brown set of workman’s footwear – though the boots, as well as a beaded bag and a light brocade jacket were folded as carefully as if they were in a shop-front window. They rested underneath the next cot.

Before the captain could summon any words, Josephine said to him, “Cly, I can’t believe you came.”

“Well, you asked me to.”

“I guess this isn’t exactly what you expected.”

“Not exactly.”

“But, you’re here.”

“Yeah, I am.”

The man on the cot said, “I’m Deaderick Early – and I don’t believe we met, last time you were passing through New Orleans.”

“I don’t believe we did. You were off in the war, weren’t you?”

“Sounds about right. It’s good to meet you now,” he said, and since Josephine had stood, he stood as well – with effort and some pain, but also with dignity. He extended a hand and Cly shook it. “And it’s good of you to come.”

“Rick, sit yourself back down,” his sister told him, more gently than crossly. “You’re supposed to be resting.”

Cly saw a chance to be helpful, so he went to pull up a stool and said, “We should all sit. We’ve got some talking to do.” But upon getting his hands on one of the stools, he changed his mind and said, “I suppose I’ll just go cross-legged,” for he didn’t think the chair would hold his weight.

Chester Fishwick took the seat instead, and when they were all settled again – Deaderick wincing and Josephine working hard to keep from babying him in front of the other men – the captain said, “So I hear you’ve got a big boat, only it’s not exactly a boat. And you want me to fly it.”

“That’s the sum of it,” Deaderick said.

While Cly figured out what else to add, and how to add it, Houjin’s excited voice carried through the windows, spouting a list of questions a mile long. Cly said, “The kid must’ve found Mr. Worth.”

“The lens-maker?” Josephine asked. “Yes, he’s here. Who’s the kid?”

“He’s apprenticing with me. Smart boy. Wants to know how everything works, and he’s real excited about that gate you folks have set up – the one with the mirrors. Norman Somers said a guy named Worth designed it, and now Huey needs to hear the details. But I’m not here to tell you about my crew. I’m here to hear about your ship.”

Deaderick took a deep breath that appeared to sting. He said, “I’m not sure how much the ladies have told you already.”

“The history of it, mostly. And I’ve seen the engineer’s drawings, the ones that show most of the workings. But I’m still trying to wrap my head around how to operate it, or get it to the ocean. I mean, I can tell from what little I’ve seen of your camp that you fellows have plenty of good machines and good mechanics to keep them running. Surely someonehere can pilot your bird. Your fish,” he corrected himself.

Chester declared, “We have four mechanics from the schools at Fort Chattanooga, and a couple of men who trained in the machine shops in Houston. So yes, we’re all set for men to make and maintain what we’ve got, that’s a fact. But the men we have … they’re drivers and sailors. They’re engineers who’ve worked on rolling-crawlers and the big diesel walkers the Rebs are using on the northern fronts. They aren’t men who know much about airships, or this kind of … watership.”

Deaderick added, “I think they could be forgiven for not knowing much about the Ganymede. Everyone who ever understood it is dead or in prison, miles and miles away from here. The Ganymedeis a tribe of one. Wallace Mumler wants to call it an undermariner, but that’s a mouthful, isn’t it? Hunley called these things submarines, so that’s what I’m sticking to.”

Josephine smiled, every bit as cool and measured as he remembered she was capable of being. “Chester and Rucker, and Deaderick here, and Edison Brewster, and Honeyfolk – they all know howit works. They can tell you what every lever means and what every button does, but not a one of them knows how to turn the thing in a full circle without so much shouting, arguing, and complicated finesse that you can’t imagine them ever moving it down the river. These men have all the paper know-how, and none of the hands-on experience to pilot the thing correctly.”

Chester added, “But like Rick just said: Nobody does. There’s no one within five hundred miles who’s been inside a submarine and hasn’t drowned.”

Deaderick looked to Josephine, whose smile had not melted. She said, “It was my idea to go hunting for an airman instead of a seaman. The sailors all know how to sail, but this isn’t sailing. The drivers all know how to drive, but this isn’t driving. It’s flying under the waves, and I think you’ll have an easier time of it. Yourinstincts will be the right ones.”

Andan Cly thought about it hard. Slowly he said, “Maybe. Maybe not. I’ve had a word with my crew, and everybody’s interested in giving your job a chance, but I’m not interested in getting any of them killed. Myself either, for that matter. So I think I’d better take a look at this submarine.”

Deaderick once again hefted himself to his feet. “Rick, baby. You should stay here,” Josephine insisted.

“The hell I should. I know that thing better than anybody, and I’ll show him around it.”

Appealing now to Cly, and to Chester, too, she said, “But it’s been only a couple of days since he was shot. He should stay.”

Chester wasn’t about to overrule Deaderick Early, and Cly didn’t know any of them well enough to intervene. So he said, “Josie, if the man says he’s fit to leave, you’d better let him. He’s kin of yours, so I won’t stand in his way.”

She relented unhappily. “Fine. But Chester, do me a favor and get Dr. Polk and have him join us, will you?”

“That achy old drunk?” Deaderick sighed. “I don’t need him watching over me like I’m a baby in a bathtub.”

“I want him here in case you start bleeding again,” she pushed. “I didn’t go through all the trouble to drag you back to the bayou just to have you drop dead because you think you’re too much of a man to take a week and recuperate.” Then she turned to Cly and said, “He was at Barataria when the Texians raided. He took two bullets, and only by the grace of God is he still here living and breathing. He’s a lucky bastard, is what he is.”

“Lucky to have such a devoted sister,” he said, and gave her a penitent kiss on the cheek.

One by one they descended the ladder, and Chester Fishwick went in search of the doctor. Josephine called after him, “Tell him to meet us at the dock!”

When everyone was back on the ground, Cly asked, “You have a doctor out here?”

“Technically. He’s a drunk Federal who was drummed off the field four years ago for killing a man on the operating table,” Deaderick replied. “That’s a hard call to make – a man on an operating table isn’t in the best shape in the first place, but if the doctor’s been drinking, I don’t guess that improves his odds any. Regardless, he patched me up out at Barataria, and Josephine brought him along.”

“I promised him some of Wallace’s grain alcohol,” she said.

Deaderick pointed at a path, a winding trail contrived from dirt ruts and planks that had been jammed into the mud for better footing. “We’re heading that way, down to the river.” He pressed one hand against his injured chest, and for a moment he went pale beneath the hue of his skin.

“Rick?” Josephine asked.

“Don’t, now. I’m all right. Come on. Let’s go.”

“Hold on.” Cly stopped him. “See that oriental boy, badgering that old guy in the spectacles? That’s Houjin. Let me grab him. He’ll want to see this.” The captain rather wanted Houjin to see it, too. It wasn’t that he doubted the knowledge of the men who were guarding the Ganymedeso jealously, but he wanted to get the fledgling engineer’s take on the matter as well. Sometimes the advantage of being young and bright is not knowing what’s impossible. “Huey, get over here a minute, will you? Get Fang and Troost if they’re handy.”

Houjin looked left and right, and didn’t spot his comrades. So he shrugged and trotted up to the group alone. Cly introduced him. “Josephine and Deaderick Early, this is Houjin. He’s going to be an engineer.”

“Good to meet you,” said Deaderick, and Josephine said something similar, though she looked at him with open curiosity.

“A bit young, isn’t he?” she asked.

“He’s young, but he does all right. Anyway, Huey – we’re headed to see the Ganymede.I thought you’d like a look.”

“Yes, sir!” he said excitedly, and almost headed off down the trail without them.

“Chester will tell your other men where we’ve gone, and likely bring them along with Dr. Polk,” Josephine assured Cly, falling into step beside him.

He wasn’t entirely certain how he felt about being so close to her again, having been so far away for so very long. But this was business, wasn’t it? And they were friends now, weren’t they? Or couldn’t they be? It’d been long enough since the fighting, the arguing, the battling of wills. It’d been enough years that the good times seemed warmer, and the bad ones were weaker, more fuzzy. Harder to recall, somehow. Surely it was like that for her, too; otherwise, she wouldn’t have called him out.

Maybe she hadn’t left their relationship as mad as he’d thought.

He resolved to have a word with the crew on the way home to Seattle, and during this word, he intended to give them all a firm understanding of why there was no earthly good reason for Briar Wilkes to know anything at all about Josephine Early.

By way of making conversation, or maybe only for the sake of business, Josephine said, “We call its resting place ‘the dock,’ but it’s no dock to speak of. We have to keep it submerged. Texas watches from the clouds, and if they spot it, they’ll claim it in a heartbeat.”

“They’ll try,” Deaderick said.

His sister chided, “Don’t talk that way. Especially not now. Texas took the island, and they could take the lake, too. I feel like a goddamn coward about it, but right now, all we can do is hide. It’s the only way to finish this operation.”

“It’s not cowardly; it’s strategy,” her brother corrected her. “I don’t want to have to defend it. We might have the firepower, but we sure as shit don’t have the manpower. And it’s hard smuggling diesel back here in decent quantities. The rolling-crawlers are ready to ride, but they can’t go more than fifty miles without refueling, so we can’t waste it.”

Houjin dived into the conversation with a question, as he was so often inclined to do. “Does the Ganymederun on diesel?”

Josephine answered. “It can, and does. But Wallace Mumler – he’s one of the Fort Chattanooga lads – thinks he can run almost anything on alcohol, if you make it pure and strong. So he’s experimenting. He keeps a still out in the trees, away from the main camp.”

“Why?” the boy asked.

“Because the still requires fire, and fire makes smoke. We keep it to a minimum, and he’s working on a converter that would process most of the smoke out of the air before anyone ever sees it – but that’s not ready yet, so for now he does it all the old-fashioned way.”

Deaderick said with a smile, “He’ll distill anything. Or by God, he’ll give it a shot. Corn works best, but from a scientific standpoint, there’s no good reason he can’t distill all kinds of things. And by God, he’s giving it a shot.”

“I bet he’s a popular fellow.”

“And how. Even the alcohol that won’t work to power anything … usually it’s drinkable.”

Josephine shuddered. “After a fashion.”

“I didn’t say it was fine wine,” Deaderick joshed her. “But after hours, when things are quiet and we’re all settled down for the night, most anyone in the camp is happy to give his latest batch of … whatever he’s brewed … a taste.”

Hiking the rest of the way down to the water was a warm, sticky experience fraught with a hundred slaps against mosquitoes and a general wish from Captain Cly that it would rain or dry up already. The heavy, humid lingering of the damp air so close against the earth, so moist on his skin … it felt like inhaling through a wet bath sponge. He’d all but forgotten the weight of it, in his ten years of absence, and though he’d been in town not even two days, he’d already forgotten the season. Springtime in the Gulf was hardly any different from its summer, though the nights were still cool enough to breathe, and the days were not yet hot enough to fry bacon on the side of a ship. It was still too warm to be comfortable, and too moist to breathe deeply.

Conversely, the springtime chill of the Pacific Northwest was not terribly different from its fall, or its winter either, for that matter. With all his heart, he missed it – even though he’d left it not so long before, and could expect to find himself once again cool as the tides within the month.

Even now it blew his mind that Josephine had preferred this sunken swamp to the cooler, clearer Northwest. Then again, back when they’d first started fighting about who should live where, she’d said it blew her mind that anyone would want to live in the rain by an ocean that was never warm enough to swim in, and didn’t even have a beach.

Then they’d fought about the differences between a beach and a coastline, and fought furthermore about what on earth she’d wear to stay warm all year if she left – and what he’d wear to stay cool all year if he stayed.

In reality, they weren’t arguments about the weather. They were always about other things. Other issues. Other matters of control, and autonomy, and money. It was the same fight again and again, regardless of the details, and it took them months to figure out that they were bickering over who was being asked to give up the most … and who would do so, for the sake of being together.

So she’d felt abandoned. So he’d felt rejected.

So neither one of them compromised, and both got what they wanted most. Or least. Sometimes it was hard to recall.

The smell of dead fish swelling in the sun invaded the usual odors of the bayou, and soon the hum of mosquitoes was matched and drowned out by the fiercer buzz of larger insects. Stagnant pools and puddles rippled with the small slaps of long-legged water birds stepping carefully among the tufts of grass, fishing with their javelin-sharp beaks; somewhere not too far away, a heavy-bodied pelican with shimmering brown feathers launched itself off the surface of the lake and into the air, its powerful wings spreading wider than Captain Cly’s arms and pumping hard to lift the big bird into the sky.

The pathway opened against a sodden, silt-thickened bank, and Lake Pontchartrain sprawled before them.

The water was quiet, save for the softly broken rushes of short waves pushed by wind, alligators, muskrats, or more pelicans with their pendulous torsos. Mostly it spread out flat and dark, its water the same shade of murk that made up the sopping bayous and the bubbling swamps. The tall, stiff grasses sagged as small white birds with spindly feet clutched at and bounced atop the vegetation. Turtles as slick and black as oil clustered on logs and rocks, sometimes ignoring the intruders and sometimes slipping away with a quiet plop. Glistening spiderwebs wider than curtains were strung between plants, trees, and the occasional piece of man-made pier blocking.

Everything, everywhere, was alive.

“This is the dock,” Deaderick said, and he leaned up against a rough-hewn banister that led to a wood-slat walkway over the water’s body. He looked as if he’d very much like to sit or lie down, but had no intention of doing so.

Houjin asked, “Where’s the ship? I don’t see it.”

Josephine flashed her brother a look that told him to stay right the hell where he was, and led the way out onto the planks. “Over here,” she told them, as she stopped to kneel at the walkway’s edge. Leaning over, she reached underneath and pulled a lever or a switch that no one could see. With a loud clank and rattling of chains much like what they’d heard at the gate, the pier began to shake. Its pilings cast ringed waves in tiny loops as the whole structure shuddered.

“Look!” cried the boy.

He pointed at a separate set of pilings hidden in the grass. These, too, were wobbling, straining to heft something enormous – lifting it up between the two structures on a platform that must have been resting on the lake floor. The pulley chains twisted and tightened, and the clattering was raspy with rust, but the underwater lift did its work.

Up from the silted basin of Lake Pontchartrain rose the hull of a grim metal leviathan.

The whole of its steel cranium sloughed off swamp water and grass, clumps of runny mud and slippery tangles of fallen moss. It reared up out of the water, its bulbous and misshapen skull hammered into a shape influenced by the airships. But even with two-thirds of its bulk yet submerged, Cly could see the design elements that made this machine ready for water, and unworthy for air.

At water level, a pair of fixed fins were mounted on either side, left and right; larger fins were barely visible beneath the murky lake. The front was remarkable for what could not be called a windscreen, but a rounded glass window split down the middle and reaching up like a forehead.

This window gave the overall impression of a nearsighted mechanical whale wearing an oversized pair of spectacles.

Through it, Captain Cly could spy seating in the ordinary configuration: one spot for the captain, two chairs on either side for a first mate and engineer. All the fixtures were bolted to the floor or the wall, in case of … not turbulence, but waves, and tides, and currents.

Cly walked to the end of the pier in order to see the back end of the Ganymede,or what was visible of it above the water.

From the rear, the ship more closely resembled an actual sea creature. The back was snubbed, and then fitted with a fin that clearly moved not side to side, but up and down; below this fin – which must serve for stability more than for propulsion – a set of flaps were mounted, maybe for steering. Below these flaps, a pair of propulsion screws jabbed, dripping with river-bottom muck.

The large round portal to the left was likely matched by one on the far side, and if Cly recalled the schematics correctly, these were vents for taking on or ejecting water in order to let the craft rise or sink more easily.

Around front, Houjin was leaning so far off the pier that a sparrow’s wing could’ve knocked him flat into the water, bouncing him off the front windows of the Ganymede. Probably, he wouldn’t have minded.

“Watch out, Huey. I don’t know if we could fish you out of there before the alligators get you.”

Houjin jerked back upright and peered anxiously into the water. “Are there alligators? I didn’t see any?…”

Deaderick said, “There are alwaysalligators. The damn things are a fact of life around here. But,” he added as an afterthought, “they dotend to keep unwanted visitors away.”

“Can we take a look inside?” Houjin asked.

“I’ll just open the hatch,” the guerrilla replied.

Josephine said, “No, I’ll do it. You hold tight.”

“I’m fine.”

“If Dr. Polk says so, then all right. And here he comes.”

“Now I need a permission note?” he argued.

“No, Ineed one. You don’t want me to worry, do you?” Without waiting for an answer, she stepped to Ganymede’s side. She anchored herself by holding on to a piling with one arm, and then she leaned out with the other to grasp a lever embedded on the craft’s upper left side. When she gave the lever a yank, a panel jerked open with a sucking pop, revealing a bright red wheel.

Josephine turned the wheel with one hand, still holding tight to the dock with the other one. Going was slow until Cly joined her, saying, “Let me.”

“I can do it.”

“I know you can, but I’m the one with the ape arms, so let me help.”

He could reach the wheel without leaning and without bracing himself, so Josephine sighed and let him at it. Cly gave it a couple of twists, and then a second, much loudersucking pop was accompanied by the sudden appearance of a round seam. It was a door, its edges announced by rivets the size of plums, but otherwise indistinguishable from the various nodules and lumps that made up the Ganymede’s exterior.

The captain glanced at Josephine, who gave him a quick nod of encouragement.

He tugged and the door squeaked open, pivoting on a thick round hinge as wide around as a woman’s wrist. A puff of air escaped the interior. It smelled like rubber, lubricant, and industrial sealant, with a hint of diesel.

“Captain?”Houjin asked.

Cly jumped. The kid had moved so quietly, so quickly to come stand at his side – right under his lifted elbow. “What?”

“Let’s go inside!”

“I’m going, kid. I’m going.”

Behind them, Dr. Polk emerged from the path, mumbling something about how he ought to be in Ohio right now, but not sounding much like he meant it. Chester Fishwick was behind him, and Cly heard other voices bringing up the rear from the camp. Fang and Kirby Troost were on their way as well.

“We’re about to have a regular crowd,” he told Huey, bracing himself on the pier with one foot, and on the ship with his other. The craft felt firm underneath him, and when he left the pier completely to straddle the door, it bobbed only gently.

Inside the round door – which admitted him, but only if he crouched – a vertical row of slats functioned as a ladder. He didn’t need it. It took only one long step and half a hop to drop himself into the interior. From this vantage point he spied a smaller, more flexible ladder rolled up and stuffed to the right. He picked it up and tossed it out the door, letting it unfurl against the exterior.

While he listened to the scrambling patter of Houjin’s hands and feet against the wood dowel rungs, he surveyed the bridge. All things being equal, it was only a little smaller than the Naamah Darling’s seating area, though the ceiling was lower, and of course the captain’s chair wasn’t tailored to his height.

Inside the craft, the architectural details were more prominent and less delicately concealed than they would’ve been in an airship, for few people would be subject to seeing them in a war machine such as this. Every exposed edge, every low beam, and every unfinished surface declared that this was a workhorse, not a passenger ship.

“Work seahorse,” he said aloud to himself.

Houjin answered him anyway, dropping down off the ladder with a thud that gave the vessel a slight quiver. “Sea horse? Maybe that’s what they should’ve called it. Why’d they call it Ganymede,anyway?”

“I don’t know. I doubt the fellows outside know either – they didn’t name it. I don’t even know what a Ganymedeis,” the captain confessed.

“Who.”

“Beg your pardon?”

“ Ganymedewas a who. He was a prince of Greece – kidnapped by Zeus, and brought to Olympus on the back of an eagle. He became the cup-bearer of the gods,” the boy said off the top of his head.

“Oh.”

“But I don’t know what that has to do with this ship.”

“I don’t either,” the captain admitted. “But look at this thing, will you?”

“I’m looking, sir. I’m looking. This, over here—,” he said, waving his arms at a central column that disappeared up into the ceiling. “What’s this part?”

Cly consulted his memory of the diagram. “I think it’s a viewing device. It cranks up and down, see that wheel over there? Try that, and see if it does anything.”

“Why does it crank up and down?”

“There are mirrors inside. It lets you look out on the surface without bringing the ship all the way up out of the water. Or that’s the theory.”

“Brilliant!” Houjin declared. He inspected the column, poked at the wheel, ran his fingers across some of the buttons and knobs … and with a deft, instinctive tug, he deployed the mirrored scope.

Cly almost stopped him – almost reached out and cried, No!But he withdrew, letting the boy inspect the scope, and turned his own attention to the bridge.

Over his head, the curved window sloped. He dropped his shoulders and leaned forward to cut his height by half a foot, and nudged the swiveling chair to the right so he could step sideways past it. He examined the console, touching its buttons. He tapped at one label, screwed onto the surface above one of the nearer, more prominent levers. DEPTH was all it read. And a series of marks scratched below it notched off feet, or yards, or fathoms. The captain had no idea exactly what they designated, for they were not marked with any corresponding numbers.

A ratcheting noise drew his attention.

He looked over his shoulder and saw Houjin walking in a circle, his face smashed up against a visor. “I can see it, sir!”

“See what?”

“The pier! The woods – or, the what-did-they-call-it?”

“Bayou.”

“The bayou! And … oh…” He paused with near reverence. “Sir, I think I see alligators – real ones, up close this time. Are they real dark, almost black? And do they look like they’re made of old leather? And do they have eyes on top of their heads, that stick out of the water?”

“Sounds to me like you’re answering your own question.” Cly smiled, returning his attention to the console – but only for a moment. More footsteps and the climbing crawl of hands announced a newcomer, Troost. And behind him, Fang.