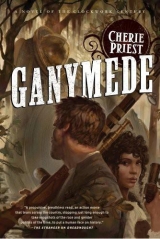

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Get a look at this, will you?” Troost said. He jabbed a thumb at the exposed metal beams, curved like ribs – like they were really within a whale, and could call themselves Jonah. “Not a lot of creature comforts went into this thing.”

“It’s not meant to be comfortable,” Cly told him. He pushed at the captain’s chair, which had been furnished with a leather pad in the shape of a cushion. It looked approximately as soft as an old book.

Fang joined Cly at the console, investigating the controls and the seats as Cly had before him, occasionally pausing over a set of lights or buttons, or a handwritten note stuck beside a switch with a daub of glue. He indicated one, scrawled on rough pulp paper. It read, forward charges – top two/aft charges – bottom two.

Cly scanned it and said, “Charges. Must have something to do with the weapons system. I’m sure it’ll all make sense in time.”

Fang showed him another note, mounted on another glob of adhesive.

“Diesel-electric transmission/propeller,” he read. “That’s almost self-explanatory, ain’t it?”

The first mate nodded, but swept his hand across the controls.

“Yeah, more notes. These fellows, they’ve been figuring it out as they go along.”

“You’ve got that right,” said Deaderick Early from the doorway. He lifted up his knees and climbed onto the round rim of the opening. He did not descend to join them, but spoke from where he was perched. “After McClintock died, and Watson was gone … we had to sort it out from scratch. We’ve messed up a lot, and we even scuttled her once by accident.”

“Ah,” said Cly. “That’s the extra smell. It’s old water.”

“We pumped her out as best we could, and left her open to dry – but there’s only so much to be done about it. She doesn’t leak,” he added quickly. “She’s just hard to clean. Inside, there’s not anything much that’ll rot. The designers got that part right. Everything you see can be swabbed down, and shouldn’t get too nasty. I’d worry about rust, but the special paint they used in here protects it pretty well. The electric system is built into the walls, sealed off tight, and the diesel engine – and the propulsion mechanics – are also cordoned off. You’d need a fuse and a keg of powder to soak it down.”

Houjin was still facefirst in the mirrorscope mechanism. He swiveled it toward Deaderick and announced, “The top of your head is huge! I mean, it looks huge. From here.”

Early laughed. “You got that working right quick, didn’t you?” He stretched up out of the doorway and waved with one hand.

Houjin waved back. “It’s amazing! And it’s all done with mirrors?” Before Deaderick could answer, he asked, “Did Mr. Worth set this up, too? Did he just make the mirrors, or did he design the scope, or did someone else do all that?”

“Mr. Worth didn’t make it, but he’s the man who told us how it works. He also improved it a bit, adjusting the angle of the mirrors and changing a few of the searching gears. What you see now, when you see Ganymede,” he said, blinking back some deep internal pain, and talking past it, “is dozens of men, working together, building on the knowledge of the men who came before us. The ship was working when McClintock died, and it was working when we first dredged it up from the bottom of the lake. But in the last six months, as we’ve been forced to figure out howit works … we’ve also figured out how to make it better.”

Cly waved at the console and asked, “Are these notes yours?”

“Mine and Mumler’s, mostly. A few might’ve been written by Chester, or one of the other lads. We’ve been meaning to draw up plates like McCormick started, and get ’em engraved. But for right now, all we have is pencil and paper, and a nail to scratch marks into the metal when we feel like we need them.”

The captain said, “Whatever works. Hey, when is it safe to fire this thing up and take it around the lake? Or is it a crapshoot, given how Texas is watching from above?”

“Safest time is always night, of course. But as far as we can tell, it’s not honestly that much different from swimming around during the day.”

Kirby Troost looked up from the control panel he was examining. “How’s that?”

“The water’s pretty dark, and even when the sun’s up, you can’t really spot the ship from the air – not unless you know exactly what you’re looking for, and even then, sometimes you can stare right at it without seeing it.”

“Spoken like a man who’s given it a try,” the captain observed.

“Absolutely. I went up in one of the Barataria ships and took a look for myself. In fact, that’s what I was doing at the bay when Texas attacked – returning with the crew of the Crawdaddyfrom doing a little reconnaissance. It was miserable timing on my part, but it was a good exercise and I don’t regret doing it. We brought that little flier over here and scanned from all altitudes, high and low, making double sure she wouldn’t draw any extra attention if we tested her out and ran her around the pond.”

“It’s a shame it cost you a couple extra holes.”

Deaderick said, “Every day’s a risk. I was bound to take a scratch eventually, and this one didn’t kill me – so there’s something to be thankful for.”

“True, true.”

The guerrilla continued. “ Ganymede’s outside surface isn’t black, but it’s such a dark brown, it might as well be. It matches the lake bottom just about perfect, especially if there’s been a storm of any kind. Then all the dead grass and moss, all that swampy stuff, it gets stirred up and pools on the surface. It’s damn near perfect camouflage.”

“Like the tents you’ve got, out in the camp,” Troost noted. “You could look down from the sky and never notice a thing on the ground. It’s nicely done.”

“Thanks. And it hasto be nicely done, otherwise we’d be dead by now. That’s the first thing I learned when I joined the bayou boys a couple years ago. Our technology isn’t everything, but it’s second only to our wits when it comes to keeping us alive. Sometimes it’s hell to maintain. Wet as it is out here, we have to paint everything over and over again, to keep it from rusting.”

Houjin finally withdrew his face from the mask at the mirrorscope. “But paint won’t keep rust away. Not forever.”

Deaderick said, “We use what Texas puts on its naval skimmers and the like. It’s made with a few extra ingredients, and it keeps things more waterproof than not. Still, we have to keep layering up the coats to keep things straight.”

The boy gave this a moment of consideration, and then said, “It’s a good thing Texas uses so much brown.”

Early laughed. “You’re right about that! We steal most of what we use, but they don’t ever notice it’s missing.”

“So when do we get to try and—” Houjin hunted for a word. “—drive it?”

“We should wait until later in the afternoon, at least. Let the shadows get good and long, and take some time to sit around with our operators. We can teach you everything we know about making this fish swim, and then I’ll hand you over to Wallace Mumler,” Deaderick said to the captain in particular.

“What can he tell us?”

“Wally’s been busy making maps – but not maps of the land. Maps of the water, of the lake out at this end, and of the Mississippi.”

Cly settled gingerly into the captain’s chair, spinning it with his knees so that he could face Deaderick, sitting up in the entrance portal. “Getting Ganymedethrough water won’t be as simple as flying at night.”

“The currents won’t be very different – air and water, they move in a similar way. And you can actually seethe water gusting around, and sometimes you can tell which way it’s pushing just by looking. But it’s true, the sky doesn’t have much in the way of obstacles, I wouldn’t think … except maybe other ships, sometimes. Hidden in the clouds.”

“That hardly ever happens, but I’ve heard of it – once in a while. And I’ve sailed right into a flock of birds once or twice, but I bet that’s not half as bad as the shipwrecks, charges, and other boats waiting at the bottom of a river.”

“You’re betting right. You’ll be piloting more blind than not. They don’t call it the Muddy Mississippi for nothing. Everything is a danger, something to be run aground on. Uneven spots on the bottom, sunken trees, boulders, roots, and worse. And out on the river, you won’t just be hiding from the forts, you’ll be hiding from commercial vessels. Mostly they’re flat-bottomed things, riverboats and barges, which you’ll need to dive beneath, or dodge. We’ll have men on the river who’ll help out as much as they can, guiding you from the topside.

“But you have to understand, once you’re sealed up inside this thing, there’s no good way to communicate with the rest of us. You’ll be on your own – no speaking amplifiers like the Texians use, or anything like that. And if you run into trouble, we might not be able to help.”

Cly squeezed the arms of the captain’s chair and looked at each of his crewmen in turn. Fang, first mate. Sitting in the next seat over already, as if he’d assumed it’d play this way all along. Kirby Troost, standing by the bay doors that led to the engines, to the blast charges, and the rest, looking like he wasn’t 100 percent certain of this after all, but was unwilling to say so. And then there was Houjin, one hand resting on the pivot handle for the mirrorscope, his face beaming with excitement because the risks meant little to him. Even if he understood them as well as he thought he did, obliviousness to death was the privilege of the young.

“Well?” Deaderick asked. “What do you say?”

Captain Cly replied, “I say it’s time for supper almost. Let’s have a bite to eat, then spend the rest of the afternoon getting to know this thing.”

Ten

Josephine waited on the bayou dock between Wallace Mumler and Chester Fishwick, with Anderson Worth, Honeyfolk Rathburn, Dr. Polk, and Deaderick Early standing by. Much as Deaderick had wanted to ride along, his sister and his doctor had given him such grief about it that eventually he’d decided it’d be easier to do as they said.

Josephine didn’t enjoy treating him like a child, but men were childlike when they were sick or injured – she knew that for a fact, and sometimes it was simply easier to insist, so long as it was for his own good. She would have done anything to keep him safe, and she suspected he would do whatever he wanted the moment her back was turned.

She watched him out of the corner of her eye. His arms were folded across his chest, one of them held a bit awkwardly because of the bandage. His injuries could have been much worse, and so far, nothing had begun to fester. His strength was returning with his appetite, and though he shouldn’t have been up and around so much – he should’ve been resting, damn him – she had to admit that for a man who’d taken two bits of lead, he looked very well.

Still, she eyed him constantly, looking for signs of weakness or a worsening state. Every breath that came with less than perfect ease, every small stumble, every wince and cringe … she cataloged them in her head and played them over and over again, constantly trying to assure herself that all was well, and he was fine.

He was a cat with eight lives left. Or seven: one lopped off the total for each bullet.

Together the small group watched the water where Ganymedewas once again fully submerged. Sealed inside it were Captain Cly, Fang, Houjin, Kirby Troost, and Rucker Little – who had volunteered, knowing the risks. If anything, he knew them better than the Naamah Darling’s crew.

Josephine had wanted to call Rucker aside before he got on board; she wanted to have a private word with him, explaining that Cly and his men didn’t know the whole truth. She hadn’t been straightforward with them, because she was afraid that if she’d given them the numbers, they would’ve balked. She’d told Hazel and Ruthie to lie, and lie they had. Ruthie’d quietly confirmed it for her while the men inspected the vessel.

“What did you tell them?” Josephine had whispered.

Ruthie had whispered back, “That it was safe. That it worked just fine.”

“And no one died?”

“Hardly anyone. I think that’s how Hazel put it. Just McClintock.”

“Jesus,” Josephine had blasphemed under her breath. “I hope nobody tells them the truth.”

“I hope they do not die,” Ruthie had added.

Josephine hoped they survived, too. She wanted nothing more than a living, breathing, successful crew to emerge from Ganymedeout in the Gulf of Mexico, at the airship carrier Valiant. But deep down, in a hard, dark little corner of her heart she did not care to confront … she was glad it was Cly taking the risk, and not her brother.

Bubbles sputtered to the surface and stopped. A wide ripple cut concentric circles across the lake and then, with an almost silent click of gears and the slip of lubricated metal, the mirrorscope’s small round lens poked up through the low ripples – like an alligator’s eyeball on a thick steel stalk.

The mechanical eye dipped once, and resumed its position.

“That’s the signal,” said Chester. “They’re doing okay.”

But Josephine noted, “They haven’t left the dock yet. I’ll hold my cheers until after I’ve seen them take it out for a lap.”

“Show a little optimism,” her brother urged. “This was your idea, wasn’t it?”

“It was. And Cly is good, but I guess we’ll see howgood.”

Honeyfolk said, “I’m not sure that’s fair. He might be the greatest pilot who ever flew, but Ganymedemight still be more than he can handle.”

Josephine wanted tell Mr. Rathburn that she was sure he’d be fine, but she kept silent and watched, because it was easier than making proclamations she was too nervous to believe in. She wrung her hands together without even noticing, squeezing her fingernails into her palms and staring down hard at the lake. “They don’t know the risk. They don’t know how bad it’s really been – how many men have died in that thing.”

Deaderick didn’t look at her. “Yeah, well. That was your idea, too.”

The ripples lurched, then shifted, and began to move.

The mirrorscope eye swiveled and aimed forward. It cut through the water’s surface cleanly, leaving only a tiny wake to mark its passage. Then it gave another quick dip and retracted again, leaving nothing to indicate that the craft had passed except for the squawk and parting of a group of ducks, bending reeds, and the peculiar sense that something heavy was just out of sight.

“They’re doing it,” she breathed.

“I’ll take the small engine rower and see about guiding them,” said Wallace Mumler, reaching for a rope that hung off the pier’s side. He drew the rope with several long, hard pulls of his arms, looping it between his hand and his elbow, until a little craft was drawn out from its hiding spot under the gray slats. Two long poles were crossed atop it, and cradled in the boat’s bottom was a trumpet-shaped device approximately the size of a tuba.

Mumler jumped down inside the small boat and used the poles to leverage himself across the water in the direction Ganymedehad gone. Upon locating it, he used one of the poles to pound two whacks against the hull. Then he dropped the horn into the water, holding it by a rubberized tube that ended in an ear-pad shaped like a bun. He held this pad up to the side of his head and hit the ship again.

Then, hearing something he liked, he flashed a thumbs-up signal at the observers on the pier. “They’re good!” he said.

It wasn’t the world’s most sophisticated system, and it wouldn’t work very well when the water was deeper, but the short system of knocks and replies served for training purposes. In case of emergency or more complex communication requirements, Morse code would be the signal – performed with a hammer inside the Ganymede,and with one of Mumler’s poles from the surface.

While Josephine watched, there was a moment of concern when the ship dug itself into a submerged bank of silt and mud, but with Wallace’s guidance and some crafty maneuvering within the ship itself, Ganymedewas extracted and continued its explorations.

After an hour of tense examination, the sun was going low and gold in the sky, and Josephine started to relax.

Ruthie had joined the party sometime before, arriving late because she’d paused to brew herself a cup of coffee before strolling to the scene. She’d watched the proceedings in silence, since there was little to say and, frankly, little to see. But now she raised the question, “Ma’am, should we head back to the Garden Court tonight?”

“I don’t know. I shouldn’t leave Hazel for too long. She handles herself all right when it comes to being in charge, but she doesn’t like doing it. Besides, if anyone notices we’re both gone, it might not look good – and I don’t want anyone looking too close at the house.” She then asked Chester, “Do you think … it’ll be tomorrow night? Or the night after? We have to move this while the admiral is still within range. Last I heard from Edison Brewster, the Valiantwill be in the Gulf only until the end of the week. Texas is eyeing it too closely for them to risk staying any longer.”

“Is Texas dumb enough to attack something that big?”

“They attacked Barataria and were successful. That can only make them cockier than they already are. The airship carrier isn’t a sitting duck, but the longer it leaves its anchors down, the more time Texas has to round up trouble.”

Chester nodded unhappily. “I know you’re right, but I don’t like it. We can’t rush this, Josie.”

“We can’t take our own sweet time about it, either,” she warned.

“It can’t be tonight,” he told her. “You’ve got to be patient.”

“Why not tonight?”

“Because tonight we have to take her overland. We need to get her into position, to dump her into the river. Then, the night after, we can launch her. There won’t be time to do both, not before sunrise. And moving something that big, it’s dangerous as hell under the best of circumstances. If the sun comes up and catches us, we’ll be found out for sure.”

“Damn it all, I hate it when you’re right. How far is it to the river from here?”

“If we can get the ship a tad north and west of here, it’ll be maybe five miles. But it won’t be five fast miles, and we’ll be mighty conspicuous as we go. The plan is to haul it over to New Sarpy and stash it in one of the warehouses on Clement Street.”

“And it’ll be almost dawn by the time you’re done.”

“If we’re lucky,” he said. “Assuming Rick didn’t use up all the luck we’re owed in one lifetime, eh?”

Deaderick said, “Nah. I’m sure I left some for this week. We might have to scrape the barrel’s bottom for it, but we’ll make it work.”

“Ma’am?” Ruthie asked.

Josephine patted at her hand to reassure her. Then, to the men, she said, “Things are under control here, aren’t they?”

“As controlled as they’re going to get,” said Honeyfolk. “Now it’s up to that crew to figure out what they’re doing. There’s nothing we can do to help from here, so you might as well head back, if that’s what you need to do. We’ll send someone ahead to let you know when we’re coming downriver, and you can catch up to the assist-boats in the Quarter. Someone’ll pick you up.”

“Ruthie, looks like you get your wish – and we’re heading home.”

“ Mais non, madame. You do not understand. I wish to stay here.” She shot Deaderick a protective, almost possessive glance. “I will watch out for the men, eh? Someone has to keep them out of trouble. I will ride with the assist-boats, when they help lead the ship down the river, d’accord?”

Under different circumstances, Josephine might’ve put her foot down, but in truth, she didn’t want to leave the men either – and at least Ruthie could send messages, report back, and watch to make sure Deaderick didn’t overexert himself. If Josephine couldn’t remain, Ruthie was the next best thing.

“Fine, Ruthie. That’s fine. And you’ll keep me posted, won’t you? If anything changes, or, or … happens?”

“You know I will.”

An hour later, Norman Somers had deposited Josephine back at the Metairie lot near the street rail station, and shortly after dark, she was back in the Quarter.

Two Texians stopped her about the curfew, but all they did was demand that she find her way indoors. She assured them that she was on a mission to accomplish that very thing, at which point, one of them recognized her and escorted her back to the Garden Court.

She thought about inviting him inside, in gratitude for delivering her back to the house without further stops or inquiries. It was always good to play nice with the men who could shut off her customer base. But not tonight. Instead, she gave him a round of thanks and shut the front door behind herself. Until it was fully closed, her escort struggled to peer past her, then gave up and left when the front room curtains were drawn.

In the lobby, Hazel Bushrod was lurking near the large desk by the stairs, keeping watch for customers. When Josephine walked in, Hazel leaped up from her seat and seized her with a hug. “Oh, ma’am, I’m so glad you’re back!”

“Thank you, Hazel. I’m … I’m glad to be back, too.”

“Liar.”

“No,” said Josephine. “I’m mostly telling the truth. It’s good to be back in a place where it’s not just me and Ruthie in a skirt. The company of men is one thing. The company of men and onlymen … that’s another.”

“How’s Deaderick? Is he—?”

“He’s fine. Or he willbe fine. He’s up and around too much, that’s for damn sure. If I had my way, he’d be lashed to a bed and forced to rest like a civilized man who’s recovering from a pair of bullet holes … not running the show as a member of the walking wounded.”

Hazel raised an eyebrow and asked, “You left Ruthie at the camp?”

“She insisted.”

“Then he might get lashed to a bed yet.”

“Oh, you stop it,” Josephine said, but she smiled. And she added, “But I want to thank you for sending Cly out, like you did. He was as well prepared as anyone could expect, and I appreciate it. But now that I’m back, I don’t suppose you could cover things for me just a few minutes longer, could you? I’m absolutely filthy from that camp, and if I don’t get a bath soon, I’ll chase away whatever customers we have left, now that this damn curfew is taking hold and sticking.”

An hour later she was back, freshly dressed and feeling fully human once more. Her hair was pinned and free of leaf litter or moss scraps, and there was no more peat beneath her fingernails.

Hazel was no longer alone in the lobby.

On the love seat under the frontmost window, much to Josephine’s surprise, Fenn Calais was happily chattering with Marie Laveau.

At first impression, they nattered as if they’d known each other for a lifetime already, but as Josephine descended the stairs and overheard more of the conversation, she realized that impression was misleading. It was a “getting to know you” chat of the strangest sort – the elderly voudou queen and the somewhat less elderly Texian, who was testing out his precious few words of French and getting a friendly, giggling reaction from the woman. She corrected him gently.

“ Non,Mr. Calais. You spellthe ton the end, but you do not sayit. You let the word end a few letters from its conclusion. Say it again: vraiment. Say it, and don’t close your mouth at the end to make the tsound. It’s not so hard, vraiment,” she added with a wink.

“Ma’am, I just can notdo it to save my life. I think the French are the only folks on earth who are harder on their vowels than us Southerners. And if I never master it, c’est la vie!”

She laughed and said, “Now I knowyou’ve only been teasing!” Then, upon seeing Josephine, stalled and perplexed on the bottom stair, she said, “Ah, my dear. There you are. Hazel told me you were in the bath.”

“Madame Laveau, yes. Hello. Welcome to the Garden Court. Can I … can I get you anything?”

“ Non,sweet dear. Only your time, if I might impose.”

“At any time. Ever.”

Fenn took this as his cue to relocate, saying, “I suppose Delphine is starting to wonder where I’ve gone off to. Perhaps I’ll just rejoin her.”

“Have a good evening, Mr. Calais,” Josephine told him, never taking her eyes off the woman ensconced on the firmly padded seat. When Fenn was gone, she took his place. She did not bother to ask how her visitor made it past the curfew. Instead she asked, “What can I do for you, ma’am?”

Mrs. Laveau took her hand and squeezed it. “I’m here because you’ll be receiving a visitor, any minute now. A gentleman.”

“This isa certain kind of business,” she murmured, half joking but half nervous, too.

“Not a customer, a visitor. And I’m not telling your fortune, dear one. I’m here to prepare you for the introduction. He’s a man you’re likely to treat with hostility, insofar as you’re able. But I’m here to tell you, you must notdo that.”

“I don’t understand.” Josephine frowned over at Hazel, who looked back anxiously.

“He’s a Texian. But he’s no part of your … present interests. He wishes to consult you, about the Dead Who Walk.”

“Ma’am Laveau, I try hard to be a hostess, and in this city that means I am compelled to be civil to many Texians, whether I like it or not. I’m sure I can find it in my heart to be polite to this one. Why is he coming here? Why would he think I know anything about the zombis?”

“He’s a Ranger, dearest. An investigating man, for a matter requiring careful investigation. And he’s coming here because I suggested it,” she said, lowering her voice and leaning close. She held Josephine’s hand tighter, and Hazel drew in her breath with a tiny gasp – reminding them both that she was in the room.

The hands that clasped Josephine’s were as thin as twigs, despite the woman’s otherwise stout appearance. Gas lamplight twinkled on the silver of her rings, and on the red, blue, and green of the gems or colored glass found therein. The queen smelled like sandalwood and sage, feathers and dust. And in her eyes, sunken with age, there smoldered a deep, grim light.

“Child, do you know how long I’ve walked this world?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Eighty years, give or take, as the Lord gives – and the Lord takes. I do not think I shall live to enjoy another one.”

“Ma’am, don’t talk that way.”

She released Josephine’s fingers and gave them a loving pat. “Why not? Such is the way of things, isn’t it? Time turns us all, and I’ve danced longer than many. I do not regret a single tune.” Her smile slipped, only a little. She restored it and continued. “But that’s why you must speak to this Ranger. He will help you, when I’m gone.”

“Ma’am, I am very confused. A Ranger?”

“Speak with him,” she pleaded. “New Orleans is home these days to worse than Texians, dearest. The zombis grow in numbers every day, and soon even the most determined nonbeliever willbe forced to face them. They must be managed now, before they become unmanageable. And I will not be able to help. These Texians who you hate so much, they are only men – only living men, and most of them would leave as happily as you’d have them gone. While they are here, you must work with them. We do not always get to choose our allies.”

Josephine sat back, staring hard at Mrs. Laveau. Was the woman dying? She looked healthy, given her advanced age. But there was something … less about her. Something missing, or lacking – something that had been stronger in their previous encounter, not even a week ago. “People have … I’ve heard that you were controlling them. Has it been true, all this time?”

“Yes. And no. I can urge them, and guide them. As you saw, I can often stop them. But bend them to my will? Command them to do my bidding?” She fluttered one elaborately jeweled hand in a gesture of bemused contempt. “Not at all. Though if it comforts people to feel that they are controlled, so let them be comforted.”

“I think I understand.”

“I knew you would. We’re two of a kind, you and me.”

“You flatter me to say so.”

“You and I both understand, as women of color and women of power … that power is too often in the eyes of the beholders.” Her right hand drew up into a closed fist, a pointed finger. The finger aimed between Josephine’s eyes. “And let me give you some advice, eh? One devilish old crone to a devilish youngone: Never, never, neverdiminish yourself by correcting the beholders out of modesty. When your beauty is gone, when your money is spent, and when your time in this world runs low … the one thing you’ll take with you into the next world is your reputation.”

Footsteps outside on the stoop came uncommonly loud, or so Josephine thought. She started at hearing them, the scrape of hard heels on the stones, and then on the steps.

Marie Laveau brightened. “Ah. Here he is now.” She rose to her feet and Josephine rose with her, in perfect time to the door opening.

It let in a gust of air that smelled sharp and softly sour, like the river before a storm. And it let in a Texian.

He was approximately Josephine’s age, perhaps as young as forty, with a truly outstanding mustache occupying most of the acreage below his nose and above his mouth. It spread like a pair of wings, as if at any time his face might need to take flight. Despite the warmth of the evening, he wore a duster and, instead of the military leather boots of the enlisted boys, proper snakeskin cowboy boots.

Josephine thought he looked familiar.

If he knew what kind of business Josephine operated, it didn’t inhibit his manners. A shapely suede hat the color of old bones rested atop his head until he removed it, revealing a pressed-down swirl of dark hair that was beginning to go light at the temples.

He said, “Ladies?” And he shut the door behind himself.

“Yes, please come in,” Josephine said, too late for it to mean anything.

Marie Laveau added, “Nice to see you again, Ranger. I’d stay and chat, but it’s time I went on my way. My daughter is expecting me, and now that I’m so old, she worries if I’m gone too late.”

He held his hat in his hands and opened the door to let her pass, then closed it again behind her, shutting the old woman out into the night, where she preferred to be – and where she met no resistance. She was gone as quietly as she’d arrived, without even footsteps to remind them that she’d ever been there in the first place.

The Texian frowned, looked back and forth between Josephine and Hazel, and shook his head as if to clear it. “Pardon me, I was just wondering how she’d navigate the curfew home. And then I realized that she’s got her ways, and I shouldn’t worry about it.”