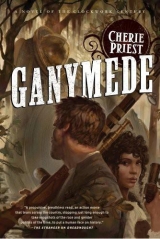

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Cardiff,” he called. “What are these things?”

Three more shots rang out, and Josephine wished to God she could cover her ears, shut them out, give herself a moment of quiet so she could listen again, and better pinpoint the things that were to come.

Not a chance. Two more shots, and then the fall of something heavy that clattered and rolled. A gun, discarded as empty. Texians always went armed, and surely two officers like these would have backup, or so she told herself as she stared with all her might – unblinking, lest she miss a crucial moment – and watched for more monsters, arriving up the back way.

They were coming right for her. She knew it, even though her whole head was buzzing from the percussion of the gunshots so nearby.

Two more uneven shapes, ambling up the walkway.

Tightening her grip, readying her aim, she gave up on hiding from the Texians, who had problems of their own. Several more shots – she’d lost count how many – and the firing ceased amid a hail of rapid-fire swearing and struggling.

“Goddammit! What are these – get away from me! Get it off me!”

“Oh God! Oh God!”

“What are they – what are they?” the colonel continued to shout.

A hail of muffled blows and the rending of fabric. A scream from the lieutenant. A bellow from the colonel. The pounding slugs of something heavy – a gun in someone’s fist? – bludgeoning strikes in the midst of what sounded like a crowd but might be as few as three or four.

It didn’t take many of them.

And here came two more.

Every shot had to count. Josephine took a deep breath. If the Texians were still alive behind her, it wouldn’t matter if they heard her now. She rose to her feet in a leap that was made melodic by the lift and swish of her skirts and the cracking shift of her undergarment stays snapping back to attention, and as the first newcomer came over the slight rise and stepped onto the planks, she blew off its face with a single shot.

A second one was right behind it. She stopped that one, too – but her mark was off, a few inches too low, and the bullet tore a hole in the thing’s throat. It tumbled to its knees but started to crawl. Josephine took a brief running start and then kicked its head with all her weight and strength – sending the bulbous, foul-smelling skull flying off into the river, where it landed with a splash.

Was that all of them?

She didn’t seeany more, but seeing wasn’t easy, and she was all but shooting blind. Whirling around to check the state of the Texians, she saw there was nothing to be done for them, even if she’d been inclined to. She didn’t mind two fewer Republicans in her city, not for a second, and if those two had known what she was up to, she’d have been thrown in jail or shot. She had no illusions about their shared humanity, or any fairy tales of cooperation to warm her.

The lieutenant was down and dying, writhing or perhaps only being tugged this way and that by the two monsters that jerked on his limbs, biting them, tearing off hunks of flesh – anything they could fit in their mouths.

The colonel was sitting upright, swinging with his gun, clapping a third one in the face while he held a fourth at bay with his hand. It wasn’t working. Number four ducked its head and tried to bite the colonel’s neck. Colonel Betters was not a young man, and his strength was failing. Any minute would be his last.

His eyes met Josephine’s. He didn’t say anything; he only looked at her there, holding the gun. She aimed it at him. He nodded, understanding in some final flash of insight that this was the last favor he was ever going to get – and it was coming from a woman who ordinarily wouldn’t spit on him if he was on fire. But this was not a fire.

She pulled the trigger.

The colonel stopped fighting. His head slumped to his chest, and now the two ragged creatures met no resistance. They dived mouth-first into his carcass, moaning their enthusiasm even as one raised its head and wailed a shaky, raspy sound … a call that was returned from several sides.

“Shit,” Josephine swore.

The howler scrambled to its knees and scuttled toward her and she stopped it with a bullet between the eyes, its body snapping backwards and falling across the colonel’s knees. Its fellow monsters, no longer content to chew on the remains of the Texians, also rose from their gorging positions and reached out for the woman, who might have the bullets to shoot her way past them, or then again, she might not.

One, two.

She hit one in the temple and it spun away, rotating like a dancer until it tripped and fell off the wharf. It thrashed in the water and then it didn’t, sinking or merely stopping – Josephine couldn’t see that far, and was distracted by the creature she’d missed with her second shot. She fired another and caught it low in the neck. The bullet was so powerful, it blew the thing back away from her – if it didn’t send it down for good.

Behind her, from the way she’d come as she’d followed the Texians to their doom, she could hear more cries, more wheezing moans, more uneven footsteps. More of the famished, snarling, semi-dead creatures.

Her heart in her throat, she squeezed off another round and took an ear and a huge chunk of brain from the skull of the next attacker.

But she couldn’t stay there, hemmed in with the wharf stretching out over the water one way and a row of shipping crates to her left; higher than she could expect to climb in broad daylight and without the restrictions of her clothing. Back along the planked walkway two, maybe three more thingswere coming – and in front of her, the edge of the pier let out onto the manufacturing row, now mostly abandoned.

She heard the rumblings of more trouble from that way, but she chose it in an instant. It was the only direction where she might be able to find an open spot and run. If she could lose them in the row, or barricade herself inside one of the old factories, she might have a chance.

No going back.

No going out to the water – she could throw herself into the waves and hope the things chasing her couldn’t swim, but she’d likely drown in what she was wearing, and the river’s currents were riptide strong, killing hardier souls than her own every day.

A last resort, then.

She’d leave it for that – only if everything else failed.

Ducking down, she grabbed the lieutenant’s lantern and ran, her felt-softened feet making barely the lightest hiss with each footfall. The lantern wasn’t broken, and that was good. It hadn’t even been turned down all the way – she wouldn’t need a match to move it, she’d only have to raise the wick and pray there was oil enough to keep it bright.

But not yet.

Not while they were rallying, and homing in. Not until she had so much distance between them that she could afford the luxury of sight.

To her left and right reared cliffs of freight, or the wooden boxes that once contained it. In places, the passage narrowed to barely a doorway’s width, but she shoved forward, thinking she might have a bullet or two remaining. She was too distracted to estimate, and estimating wouldn’t do her any good. Either she had more ammunition or she didn’t.

She zigzagged through the maze and into an open stretch with muddy floors or no floors at all. Tripping, then recovering, she saw three lumbering shadows approaching from behind and to her left – and one more closing in from directly ahead.

To her right, at the far end of a wide pier, squatted an old oyster-shucking facility that had long since moved to a brighter part of town. It was partially boarded and none too inviting, but any port in a storm, Josephine figured. She was on the verge of dashing toward it when some new presence caught her eye, and she hesitated.

A small, still silhouette stood near the wharf’s edge, outlined against a sky-high stack of folded nets that no one had used in half a century.

“Settle down, child. Give me some light,” the silhouette said.

Stunned, Josephine stood there. From two sides, then three sides, the creatures came closer.

“Child, you heardme. Raise the lamp.”

She recognized the voice, which in no way made the speaker’s appearance less stunning. Josephine said, “Ma’am?” and then hastily, as if she’d only just remembered she was holding the thing, lifted up the lantern and turned the crank to raise the wick. She did this in a rush, rolling the small metal knob and making the glass-cased lantern into a brilliant beacon in less than a second.

It was counter to all sense. The creatures could see her more clearly. They knew where she was and that she was virtually trapped, if indeed the mindless things could be said to truly “know” anything at all.

And now the monsters could see the speaker, her shape shrunken by tremendous age.

The woman was sturdily built and nearly squat, as if the years had melted a larger woman into something smaller and wider, but no less commanding. On her head she wore a feathered black turban fixed with a gem that couldn’t possibly have been real, and across her shoulders hung a long red jacket in a faux mandarin style. It flowed neatly over her dove gray gown, and from the bottom hem of this gown peeked two small black points – the tips of her shoes.

In her left hand she held a cane made of knotted wood. Her ring-covered fingers curled around the top, her jewelry flashing like sparks off a flint.

Josephine would sooner have run right into the arms of the nearest monster than tell this woman no. She held the lamp up high, letting its light douse the scene, bringing whatever terrible clarity it was bound to show.

The ancient colored woman in front of the nets raised her cane until she held it by the center, in her long-fingered fist. She swung it back over her head for momentum, and brought it crashing down against the coal-black column of a broken gas lamp that hadn’t been lit for years. The single resulting gong reverberated across the wharf, radiating in a wave that shook the boards beneath Josephine’s feet and brought every flesh-eating beast to a sudden, total standstill.

They posed statuelike and utterly unmoving, staring into space or at the newcomer. Even their gnawing, slathering jaws ceased their eternal chewing.

“Ma’am Laveau,” Josephine croaked. Then in French, “I don’t understand.”

In French the woman replied, “What’s to understand? Come here, dear. Come to me.” She beckoned with her free hand. “The zombis won’t be so cooperative forever.”

As if it’d heard and recognized the truth of this matter, the creature nearest to Mrs. Laveau shook its head. The old lady shook her head, too, and reached into a pocket – from which she withdrew a small bag filled with powder.

She blew a pinch of the powder into the monster’s face and it flinched. In that flinch, even at a distance, Josephine could see a glimmer of what had once been human; but it was gone as quickly as it’d appeared.

Once again, the thing was immobile.

“Come, child. Let’s go. We’ll walk, and they’ll stay.”

“For how long?”

“Long enough. You trust me?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Then walk with me.” She pocketed her powder and beckoned again.

This time, Josephine obeyed immediately. The lantern shook as she ran toward the old woman, and the boards of the wharf creaked beneath her feet. Her fear was a shocking, unfamiliar thing, and her body was so prepared to fight or run or die that her hands quaked and her teeth chattered, but Mrs. Laveau patted her shoulder and smiled. “There, you see? The dead must be reminded of their place.”

Four

Captain Cly closed the enormous door behind himself and kept his head low as he descended the stairs. Two floors deep, beneath the initial bank basement where the door was located, the “vaults” remained one of the safest corners of the city – the deepest, most secure, and most like a collection of ordinary homes. This bunker-within-a-bunker also served as storage for the most direly needed essentials: clean water, ammunition, gunpowder, gas masks and their accoutrements, and grocery supplies to keep the population fed.

Over in “Chinatown,” nearer the wall’s edge on the far side of King Street Station, the oriental workers kept stores of their own, as their food preferences did not strictly overlap with the doornails. But in the last year, some of the doornails had taken to wandering toward the Chinese kitchens in search of unfamiliar food – while likewise some of the Chinese had shown an interest in dried salmon, occasional fruit tarts, and intermittent baked sweets.

Food was a language all its own. And it was in no one’s best interest for anyone to starve.

The halls were not particularly mazelike, and they were as well lit as anything else beneath the city’s surface. The ceilings were lower than Cly might have preferred, but this set the vaults apart from few other places in the world; so he watched his forehead and made his way along the first corridor without complaint, silent or sworn aloud.

From the stairs at the other end he heard someone approach, moving with an uneven gait. Before the other man’s head could rise into view, Cly called out a greeting. “Swakhammer, is that you?”

Jeremiah Swakhammer appeared with a lopsided grin and a cane. “Yeah, it’s me. You heard this thing tapping, did you?”

“You’ve never been too light on your feet,” Cly said, extending a hand, which Swakhammer shook. “But now that you’ve got a third leg to bang around, sure enough. I know the sound of you.”

“I won’t have it much longer, maybe. That crackpot Chinaman doctor Wong says if I’m careful, my leg will be right as rain within another few weeks. I might not even have a limp to show for it.”

“That crackpot Chinaman doctor saved your lousy ass, Jerry. Don’t act like you don’t know it.”

“I do, I do,” he said. The grin stayed put, even spreading. “But he puts the most god-awful muck on me – these salves and creams – and he makes me drink teas that taste like tobacco simmered in horse piss.”

Cly was not altogether unfamiliar with Chinese medicine himself, having spent time in San Francisco and Portland with his first mate, Fang. “Do they work?”

“Mostly. I think.”

“Then quit your bellyaching, eh?” The captain slapped Swakhammer on the back, just to make him wobble. Jeremiah was a big man in his own right, but built wide – whereas Cly was built tall. “You ought to buy him flowers, next time you see the topside!”

“Yeah, that’s pretty much what my daughter said.” The words came out of his mouth a little funny, like he wasn’t accustomed to referring to anyone that way. “But she’s a tyrant of a thing, just like that doctor. Must be common to medical folks.”

“It’d shock me silly if any child of yours was a pushover. Speaking of her, how’s she doing? Is she settling in here to stay, or thinking of heading home?”

Swakhammer shifted his shoulders and gave half a shrug. “She’s doing good – she gets on great with Dr. Wong, and helps him out down in Chinatown, and around here, too.” A note of pride crept into his voice when he added, “She’s as tough as me and twice as smart – so she fits in all right with the other women we got down here.”

“When am I going to meet this kid, anyway?”

“She’s no kid, not anymore. But you can meet her right now, if you want. I think you’re headed right for her. You’re looking for Briar, aren’t ya?”

Captain Cly’s perennial flush bloomed around his collar. “I was … well, sure. Headed over to see her, I suppose. But I’m looking for Houjin, too. And he’s usually clowning around with her boy.” Suddenly it occurred to him to wonder, “But what’s your girl got to do with it? Did somebody get hurt?”

“Briar’s all right, since that’s what you’re really asking.” Swakhammer said, “Come on, I’ll walk with you, and introduce you to my tyrant offspring.”

Cly fell into step beside Jeremiah, and together they strolled around the next corner, down to the next flight of stairs. “Is something wrong with one of the boys?”

“Zeke got himself scratched up. Those kids were out in the hill blocks – they’d gone through Chinatown and let themselves up near one of the pump rooms, poking around at the big houses up on the hill, or what’s left of them.”

“Scavenging?”

“Playing around, is my guess. Boys do dumb stuff. Anyhow, he fell on something – or fell insomething. I’m not too clear on the particulars, but they can give you the story.”

“Will he be okay?”

“Looks like it. He’ll be walking around like me for a while, dragging one foot behind him. But he didn’t break anything, so he’ll wind up with a scar and not much more for his trouble. As long as it doesn’t fester.”

By way of announcing himself, Swakhammer leaned forward and knocked on a door that was halfway open. He poked his head around it. “Everybody decent?” he asked. It was a joke between him and his daughter, after she’d walked in on him while the doctor was helping him bathe. Ever after, he’d insisted that she knock and confirm decency before entering.

But she usually didn’t.

“Decent as we’ll ever be,” Mercy Swakhammer Lynch called back her father’s own favorite response. “Didn’t you say you were headed topside?”

“I did,” he confirmed as he stepped inside. “But then I ran into thisguy, and I realized you hadn’t met him yet – so I figured I’d show you off.”

“Show me off?”

Andan Cly followed Jeremiah Swakhammer inside, doing his best to make himself look smaller. An exercise in futility, given that he could’ve reached up and placed both elbows flat on the ceiling, but he hunched anyway.

The room was large and quite bright, due to Mercy’s insistence that she couldn’t work in the dark, goddammit, and a place with so much potential for injury and illness ought to have some kind of clinic … or if nothing else, a room that could serve as one in a pinch. She’d picked the empty “apartment” next to her own sleeping quarters and stocked it with every gas lamp, oil lamp, candle contraption, and electric lantern at hand, and with the help of Dr. Wong, she’d gotten the place more or less serviceable.

Now she was staring intently at Zeke’s leg as he lay flat on a table, grimacing for his life. She wore a set of lenses strapped to her face, helping the light show her what the trouble was. When she looked up at her father and his friend, her eyes were as big and strange as an owl’s.

“Hi, there,” Cly said to her. “It’s … not MissSwakhammer, is it? Jerry said you were married, once.”

“Widowed,” she said. “It’s Mrs. Lynch if you like, or Mercy if you can’t be bothered.”

“Nice to meet you. I’m Cly. I have a ship, and I swing through every now and again. If you ever need anything, you can let me know, and I’ll try to pick it up for you.”

“Thank you for the offer. I’ll likely take you up on it one of these days.” She used the back of her hand to shove a stray bit of hair out of her face. Her locks were lighter than Jeremiah’s, on the dark side of blond and worn in a braid that was knotted at the back of her neck. Even though she was seated, Cly could see that there was something of her father in her shape. She was too sturdy to be called slender, and her strong, straight shoulders were a direct inheritance.

Zeke made a muffled umphnoise when she dived back in with the needle, stitching a long, jagged gash with swift, sure strokes. He said, “Sorry.”

Mercy said, “You’re doing just fine. I’ve seen bigger, older men be worse babies than you by a long shot.” It was probably true. Before coming to Seattle at her father’s behest, she’d worked in a Richmond hospital, patching up wounded veterans.

Zeke knew this, and he said between gasps, “I could be a soldier, you know.”

“What are you now, sixteen or seventeen?”

“Sixteen.”

She nodded, and squinted. “Old enough,” she said, but something in her tone suggested she’d seen younger. “I don’t recommend it, though.”

“I ain’t looking to join up,” Zeke assured her, then bit back another yelp.

Cly noted that Zeke’s mother was not present, but he assumed she’d return before long. He went over to a seat – in the form of an old church pew someone had hauled down to the underground – and made himself comfortable. Swakhammer joined him. Between the pair of them, they occupied almost half of it.

“It’s just as well you’re not interested in fighting,” Cly told the boy. “You’d give your momma a fit.”

Zeke gave a pained laugh that ended in a gulp. “Shit, Captain. You know her. She’d probably sign up and come to war after me.”

“I do admit, there isa precedent,” he said. He leaned back and made a halfhearted effort to get comfortable. “What happened to you, anyway? And where’s your partner in crime?”

Mercy answered the second question before Zeke could unclench his jaw again to answer the first. “Houjin went back to Dr. Wong’s to pick up some balm for the bruising that’s going to come with this cut. Mostly I needed him out from underfoot. He was hovering like a hen.”

“Feeling guilty,” Zeke mumbled. “ He’sthe one who dared me.”

“Dared you to what?” asked Cly.

Zeke sighed, a ragged sound that was drawn in time to the needle threading through his skin. He craned his head around to look at the men on the pew, giving himself an excuse not to watch what was happening to his leg. “We went hiking up the hill, where there aren’t so many rotters. Hardly any of them, really. But there are a lot of big houses, where the merchants and sawmill fellows used to live – and Houjin said some of them hadn’t been bothered since the blight.”

Swakhammer shook his head. “I find that unlikely.”

“You never know,” the boy replied, a hint of his opportunistic optimism shining through even now. “And even if someone had already gotten inside, people miss things. So we thought we’d go take a look.”

Mercy murmured, “And how’d that work out for you?”

“We found a whole drawer full of viewing glass.” He referred to glass that had been polarized, so even trace amounts of blight gas could be detected. This glass was helpful to have around for the sake of detecting leaks, but it was worthless aboveground – given that the gas was absolutely everywhere. “And we found some canvas, a whole bunch of it folded up inside a wagon.”

“Would this be the same wagon you fell through?” Mercy asked.

“I thought it’d hold! It was one of the old covered kind, abandoned back behind a real tall house near the wall’s east edge. Someone had been using it to store junk, but junk is sometimes useful. Houjin said he wouldn’t climb inside it, and I said he was chicken. So he dared me to do it instead, and I did. But the floor didn’t hold, and—” He gestured at his leg without peeking at Mercy’s activities.

The nurse paused and reached for a rag inside a bowl of water. She wrung it out with one hand and wiped at the wounds, which had mostly stopped bleeding. “And congratulations, fearless explorer. For your reward, you get thirty stitches.” She lifted his leg by the ankle and turned it over to get a better look at his calf. “Maybe more than that.”

He groaned. “My mother says she’s going to kill me, but she’ll wait until I can run again, so I can have a head start.”

“Mighty generous of her,” the captain said. “Considering all the times she’s told you not to go exploring on the hill.”

“Exploring on the hill by myself. I wasn’t by myself. Momma said I was obeying the letter of the law, but not the spirit. Apparently that ain’t good enough.”

“Speaking of your mother, where’s she at?” Cly said with all the nonchalance he could muster. “I thought she’d be here, pacing around you.”

From the doorway, Briar Wilkes responded. “I went to hit up the bottommost storage room, looking for a pair of pants no one wanted so I could cut off one of the legs.” She held up a pair of Levi’s that had probably once belonged to a logger. “They’ll swim on you, so you’ll have to belt ’em. But I don’t think anyone will miss these things, and if anybody does, he can take it up with me. Hello, Jeremiah.”

Andan Cly stood up, but Swakhammer only nodded in her direction. He figured she wouldn’t begrudge him the gesture, since his leg was still on the mend. But the captain couldn’t stop himself, and didn’t try.

“Weren’t you down here just last week?”

“It’s a slow season, and I felt like coming back.”

“You must be the strangest man alive,” she teased.

“Maybe that’s it. Maybe I’m just looking for the company of my own kind.” He smiled, and since he was up, wandered over to Zeke’s leg to take a look at the damage. The boy’s skin was snagged and torn, but his muscles were intact, and Mercy Lynch was a formidable seamstress.

Zeke winced as the curved needle dipped again, and shuddered as the thread slipped through his skin.

Cly said, “Before long, you’ll have one hell of a scar to show off. Girls love scars.”

“They do?”

“They’re always a conversation-starter.”

“I just bet they are.” Briar only half stifled her smile as she added, “Except, come to think of it, I don’t believe we’ve ever heard any stories about yourscars. I assume you have some, somewhere.”

Cly tried not to look at her and mostly failed, his gaze darting back and forth between the morbid sight of Zeke’s mangled leg and the petite, curly-haired object of his truer interest. “None of mine are very interesting.”

“I find that difficult to believe,” she pressed. Her eyes followed him as he shuffled from foot to foot.

“Captain,” Mercy Lynch said sharply. “You’re standing in my light. Am I going to have to send you errand-running like your junior crew member?”

“Um—”

Before he could form a smarter reply, the nurse declared, “All of y’all, this is silly. I don’t need an audience, and neither does my patient. Everybody out,except you, Miz Wilkes, if you’d care to stay and look after him.”

“Funny thing is, I don’tcare to,” she said. She brought the pants over to Zeke, who stretched out his hand and took them. “I’m glad he’s all right, and I’m glad you’re here to take care of him – but I’m still none too pleased with him, and anyway I don’t think he needs the comforting.”

“I could use a shot of whiskey,” Zeke tried, because hope springs eternal.

“You could use a boot to the rear end, but you’re not going to get that, either. Yet.”

Mercy said, “I’m sorry I don’t have any ether or anything. I know this doesn’t feel very good.”

“It’s not that bad,” Zeke fibbed.

“You’re a liar. Still, I wish I could give you something for the pain. I think I’ll put that at number one on my wish list, Captain.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“You offered to make a supply run, and I’m telling you about a supply I could use.”

“Oh. Sure. Just put it down on paper, and I’ll take it with me when I leave.”

“You’re leaving right now,” she reminded him. “But come back in an hour. I’ll have him finished up by then, and I’ll start considering my inventory. Now, what’s everyone standing around for? Didn’t I ask for peace and quiet?”

“Yes, ma’am!” Swakhammer said to his daughter with exaggerated deference. “I’ll pick up my sorry old bones and be on my way.”

Captain Cly stood aside to let Swakhammer pass, which also allowed Briar to slip out underneath his arm on her way back to the door. He stopped her by saying her name the way he always did. “Hey, Wilkes.”

“Cly?”

“Suppose I could have a word with you? For a minute, if you can spare it.”

“I was headed down to Chinatown to scare up some supper. You care to join me?”

“Yes,” he said quickly. “I mean, sure. Fang’s probably down there anyway, and Houjin will wander over once Mercy shoos him away again – or that’s my guess. I’ll be leaving for a long trip soon, and if he wants to come, he’ll have to get himself ready.”

“A long trip?” Briar repeated. “How long, and are you taking off soon?”

“Might be gone a few weeks, but I’ll stick around until morning. Everybody and his brother wants to add something to my shopping list.”

“Have you been offering?”

“I suppose I might’ve been.”

“Then it’s nobody’s fault but your own.” She bumped her shoulder against him, and he pretended to recoil – as if she’d knocked him so hard, she’d sent him off balance.

They made a funny pair, walking together back up the way Andan had come. Him so tall, he had to duck at every doorway. Her so comparatively small that the top of her head barely reached his chest. The captain felt conspicuous beside Briar Wilkes; he felt his height more acutely than usual when he had to crane his neck to look down at her, and she had to twist herself to look up at him.

But he liked it when she did.

Once upon a time, she’d been a notorious girl – a pretty teenager who’d run away from home to marry a man twice her age. But sixteen years, widowhood, hard work, and raising a son alone had taken away the imperious tilt of her nose. (Cly remembered it from a drawing he’d seen, a wedding announcement he recalled from ages ago.) The intervening time had worn away her wealth, her softness, and her youth – but not the symmetry of her face. And for everything the years had claimed, they had given something in return.

At thirty-six, she was a patient and confident woman.

She was also the sheriff of Seattle, insomuch as the walled city had one. Her father had been a lawman who died a folk hero, obeying the spirit of the law if not the letter.

She’d never intended to replace him. She’d intended to live and die a rich man’s wife in a house with expensive furnishings and silver cutlery, pampering a brood of well-dressed children who played the piano and learned to ride horses with perfect posture. But time had had other ideas, and now she wore her father’s hat, his badge, and his belt buckle engraved with his initials, MW.And even the underground’s newcomers knew who she must be, whether they recognized her as Maynard’s daughter or not.

Cly lifted the big vault door and held it up while Briar climbed past it, into the subterranean underworld that passed for “outside.” He followed her, asking, “What’s the fastest way to get where we’re going? I’m still learning my way around down here.”

She paused with her hands on her hips, checking the signs and finding her bearings. “This way’s fastest in the long run. The other two ways I know are roundabout, and I don’t know the tunnels so well myself. Every time I think I’ve got my directions figured out, I turn around and wind up lost.”

“You’ve been lost down here?”