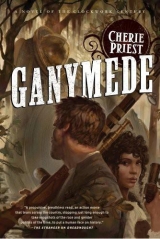

Текст книги "Ganymede"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Thank you,” he said to her, and he reached for his money. “I might skip it, like you said. There’s nothing over there that’s so important I can’t pick it up someplace else.”

He paid for his telegram and ushered Houjin out of the office, back into the street, before the boy could unleash his insatiable questioning upon the woman. It worked, but that meant Cly had to answer all the questions himself.

“Do you think she’s right? Do you think the docks are all gone? I wanted to see the pirate bay.”

“I don’t know if she’s right. I don’t know if the docks are all gone. And I wanted to see it, too, for the rum and absinthe moves cheaper over there – without the city, the state, and the Confederacy all taking their taxes on it. Now I’m not so sure.”

“Are we going to stop there anyway?”

“Let me think about it.”

Back at the docks, the excavation and return to order were under way, and Fang was helping someone beneath an overhang. His head and hands were buried under a tank, and two other men were bracing it up on a set of jacks. One of them turned to Cly and said, “Lines are all clogged up, but we’re clearing them out now. We’ll have these ready to start fueling again in a few minutes.”

“Thanks, Fred,” Cly told him.

“You know these guys?” Houjin pounced into the conversation.

“Sure. That’s Fred Evans, and underneath with Fang – that’s Dale Winter, isn’t it?”

From under the tank, someone called, “Cly, that you?”

“Yeah, it’s me.”

“What are these tanks for? Is this where you make the hydrogen? How do you do it? How did the lines get clogged? Do sandstorms always do this? Do—”

“And who’s this?” Fred Evans looked quizzically at the boy.

Cly sighed. “This is Houjin. Call him Huey if that’s easier. He’s learning to fly with us, and this is his first big trip away from home.”

“You’re a more patient man than I am.”

“Not sure if that’s true or not,” the captain said. “Is there anything I can do to help? We need to hit the sky.”

“Not much. I think they’ve got the bottom tubes just about cleaned, ain’t that right, fellas?”

Dale Winter said, “Uh-huh,” and Fang flashed a thumbs-up sign from under the crate.

“Then I suppose I’ll get out of your way. And I’ll take himwith me,” Cly said with a nod at Houjin.

“But I want to stay and watch – I’ve never seen the hydrogen generated before, and I might need to know someday. I especially might need to know if we’re going to start a generator of our own, back home,” he pointed out.

The captain didn’t want to admit that the kid was right, but before he had to, Fred said, “Don’t worry about it, Cly. He can stay, and he can ask questions. You thinking about setting up a dock for yourself?”

“Back in Seattle, one of these days. Maybe soon.”

“Seattle? That backwater? I didn’t know anybody lived there anymore.”

“You’d be surprised. And I’ve been talking to the … uh … well, he’s kind of like the mayor,” Cly exaggerated. “We’re thinking a hydrogen dock would be a good thing for the town.”

“Would you be running it?”

“I think so, yes.”

Fred nodded thoughtfully. “Not a bad way for a man to retire. The work’s not so hard, and I guess out there up north, you don’t have these god-awful dust storms to worry about.”

“No, no dust storms.”

Cly retreated to the Naamah Darling,leaving Houjin to learn about the system. Though the lad had never undergone any formal education, he was smarter than almost anyone the captain had ever known – a boy with an easy mastery of everything with gears, levers, valves, wires, or bolts … to say nothing of his flair for languages.

Fang understood Portuguese, English, and both Mandarin and Cantonese – but he couldn’t speak any of them, and most of his communication with others came in the form of hand signs or written notes. Cly himself knew a smattering of French, left over from his days lurking about New Orleans, and he could not read or write Mandarin, but he spoke enough to make himself understood … if the other speaker were very, very patient. Otherwise, he was limited to the English he’d learned from the cradle onward, and it was sometimes insufficient.

But Huey had a brain like a sponge.

Born to speak Mandarin, he’d picked up Cantonese alongside it and learned English from Lucy O’Gunning and some of the older white men who lingered in the underground. As soon as he could read the English, he’d demanded books composed therein, and before long, he’d developed a better vocabulary than any of the native English speakers the captain knew. Now Fang was teaching him Portuguese out of a few novels, and lately Huey had shown some interest in Spanish.

In short, the Chinese boy could read, write, and speak almost everything useful. And he was busy learning what he didn’t already have a handle on.

The captain himself had only a fourth-grade education, and he was occasionally intimidated by the well-read, the well-heeled, and the well-to-do. However, he was not at all stupid, and he was quietly thrilled by the idea of grooming someone like Houjin for his crew and company. Andan Cly had been a pirate so long, he didn’t care that the boy wasn’t educated, or of age, or even white. He’d learned the hard way that you take the best crew members for the job, regardless of the particulars, and if the best man for the job of engineer was a teenage boy with a ponytail, so be it.

Technically, Kirby Troost was the ship’s engineer. And technically, Cly called Houjin his “communications officer.” But realistically, everyone on board performed whatever task was needed, and the duties were fluid.

Kirby Troost was sitting outside the bobbing hull of the Naamah Darling,still clamped to its pipe dock and awaiting a Goodyear tube of gas. “Cap’n,” he greeted him with a nod of his head.

“Kirby. You got any business that needs attending, while we’re here?”

“Already attended to it. And I’ve got a bit of bad news. There’s trouble at Barataria, sir. Texas stomped through it a couple nights ago.”

“Oh, good,” Cly said. Then, quickly, he adjusted the sentiment. “I mean, your bad news is the same as my bad news, so between the two of us, there’s just one parcel of it.”

“Ah. Right you are, sir. And it could be worse. We could’ve been there when the Texians put their boots on the ground.”

“You’re right about that. Say, how’d you hear about it?”

“Begging your pardon?”

The captain said, “I only learned it through the tapper girl. You got a source out here moves faster than the wires?”

“No, sir. Ran into some old acquaintances, that’s all. They flew over Barataria the day before yesterday, and thought to tell me about it. What did the tapper girl tell you?”

Old acquaintances … that could mean anything, but the captain didn’t press for more. “She said she’d heard lots of rumors, but nothing firm. What’d your acquaintances have to say about it?”

“Only that it happened, and the surviving bay boys are digging themselves out as best they can. Texas didn’t get everybody – a bunch of the brighter fellows holed up in the old Spanish fort, and rode it out that way. But the place has been done a real blow. It’s a shame.” Kirby shook his head. “There ought to be some kind of exemption, for someplace with such a long and colorful history.”

“You think they ought to leave it alone, just because it’s been there awhile?”

“Something like that. Mostly I want to get liquor without paying taxes six ways from Sunday, but a man can’t have everything like he wants it. But I won’t lie to you, Captain. It smells funny to me. Word in the clouds has it, Texas was looking for someone in particular, or some thing. Nobody knows what. Or if anybody does, nobody’s talking.”

If no one was talking to Kirby Troost, it must be a secret piece of information indeed.

Andan Cly sat down on the ship’s steps, which were unlatched and dangling down. His sudden weight made the stairs sway, until they settled against the ground beneath him.

Troost sat beside him. He pulled out a canteen and took a swig of something that wasn’t water, and he asked, “Our business wasn’t with the bay, though, was it?”

“Nope. We’re running for the city, and I’m going to swing by the Vieux Carré to … help out an old friend.”

“An old friend?”

“She wants me to make a short trip for her.”

“She does, does she? I don’t guess you have any more details than that.”

Cly shook his head. “I’m sure it’ll be fine. It should be real quick.”

“We flying Miss Naamah?”

“I don’t think so. But when I do know, I’ll pass it on. Until then, don’t worry about it.”

Kirby took another swig. “All right, then. I won’t.”

And back into the sky they went, into the currents and clouds that would take them the rest of the way south, the rest of the way to the Gulf.

Seven

The blower was a flat-bottom boat that sat high on top of the water, like a very small barge. Barely big enough to hold all three passengers without dipping below the rippling waterline, the craft shuddered until everyone sat very still. Behind them, a large diesel-powered fan loomed like a tombstone.

No one said anything until Josephine stated the obvious. “We’ll need something bigger to bring Deaderick out, won’t we?”

Ruthie shivered and drew her jacket closer around her shoulders, but said, “To be sure, but we can find something bigger on the island, non?”

“Sure,” Gifford agreed. “We’ll find something.”

“Something that still floats, or still flies,” Josephine muttered. “They can’t have grounded or sunk everything.”

“Yes, ma’am, I think you’re right,” he said. But something in his voice said he was afraid they were all wrong, and this wasn’t going to work at all. His small electric torch sputtered, and he turned it off, leaving them all in absolute darkness except for the moon overhead, halfway full and surrounded by a fogged-white halo.

Suddenly the crickets and frogs seemed very loud, and the buzzing drone of a million night bugs hummed against the background splashes of tiny wet things moving in and out of the water, up and down the currents, around the tree-tall blades of jutting grass.

“Does this thing have any lights of its own?” Josephine wanted to know.

Gifford Crooks leaned across her knees, saying, “Excuse me, ma’am – and yes, she does. Good ones, even.”

“Better than your flambeau?”

“Much better. This is a rum-runner, you know.” He lifted a panel and threw a small switch.

With the faint click and a fizz of electricity, a wash of low, gold light blossomed at the front of the boat.

At the fan’s base, a rip cord dangled from a flywheel. He gave it a yank and the engine sputtered; a second fierce tug and it grumbled to life. The fluttering gargle was terrifyingly loud, and the rushing suck of the blades made their hair billow backwards. Gifford Crooks adjusted the throttle, lowering the speed and dampening the drone until it was a low, throaty putter.

“Hang on, ladies. It’s going to get bumpy. And damp. Sorry.”

Slowly the boat turned as he drew on the steering lever, its caged fan churning the air and the water, too, so low in the marsh did the blower sit. The spray blew into the air, and a mist of swamp water and algae settled into their hair, onto their shoulders, and across their laps.

Little craft like the blowers were built to navigate the difficult terrain between land and water – the wet, deep places clogged with vegetation and animal life, thick with mud and unpredictable depths. They were made to skim the surface, to flatten the tall, palm-width grasses and slide across them, powered by the enormous fan – and aided by a pair of wheel spokes mounted on either side. The spokes were lifted up like a gate around the passengers, until and unless the boat became stuck. If the fan became tangled or the passage was too thick with grass or muck, the spokes could be dropped, and the band moving the blades could be rehung to move them instead. It was a jerky, difficult, last-ditch way to get the craft through the sopping middle-lands, but it almost always worked.

Never quietly. Never smoothly. Never without soaking the occupants.

They puttered through the marsh in silence, for speaking would’ve required louder voices and added more noise to the night than the diesel engine’s drone. Gifford Crooks navigated by some manner he didn’t feel compelled to share; he looked up at the sky from time to time, so Josephine assumed he went by the stars like the sailors, or perhaps his sense of dead reckoning was better than the average landlubber’s.

As the evening ticked by, the moon rolled higher.

And all the while, as Gifford manned the steering lever and peered intently at the flush of light before the craft, Josephine and Ruthie huddled close together, thanking their lucky stars that the night wasn’t any colder, and their destination wasn’t any farther. The whipping slaps of saw grass whispered awful things against the craft’s hull, and the loud sliding splashes off to either side warned of large animals with rows of sharp teeth and beady, slitted eyes.

Texian soldiers or Confederate spies were not the worst things in the marshes, a fact that the travelers knew, but tried to ignore.

And when the blower would muck across a particularly pungent patch of moldering black water that smelled like death, they all thought of alligators and how those terrible brutes preferred their meals drowned, sodden, and half rotted to pieces.

In time, the travel numbed them with its treachery. When every shadow could mean discovery and every splash might indicate the approach of a creature so big, it could tip the boat … even terror became mundane. As the hour came for the engine to be cut and the oars to be deployed along with the spokes, it was a relief for everyone on board.

This was different, at least. In a struggle against the algae-thick water by hand, and they had some agency over their own progress and survival.

Now, as the growling mumble of the engine was choked off into quiet, they would move themselves the rest of the way. This small measure of control should not have satisfied any of them so much as it did, but Josephine gladly grabbed one paddle and Gifford Crooks took the other.

“Ruthie, you may have to crank the spokes if we get stuck. Can you do that?”

“ Oui, madame,and if you are tired, you can trade places with me. Moi aussi,I can paddle.”

“I know you can, dear. And I might take you up on that, but not quite yet.”

So the churning gargle of the motor was replaced by the soft slip, strike, and dip of the long, flat paddles, moving in an arc on either side of the craft, drawing it farther and deeper south and west. Josephine didn’t realize at first that she was holding her breath between strokes, but when she did, she used those quiet seconds to listen for any signs of humanity.

Within an hour, she was rewarded by the murmur of big engines rumbling in the distance, and as they came closer still, the engine noise was augmented by chattering shouts projected by amplifying cones. And, with gut-churning intermittence, the background drone was punctuated by explosions – fireballs from hydrogen tanks meeting stray weapon fire, burnishing the horizon’s edge with bubbles of warm, yellow glow that flared, ballooned, and collapsed.

Josephine heard Texian accents, and the shifting gears of enormous ships, and the humming overhead purr of dirigibles. When she looked up, she could see them, mostly painted brown – some displaying the large lone star from the Republic’s flag. A few searchlights were poking down, their diffuse beams casting tubes of light that turned vague in the low-lying fog over the marsh grasses; but those lights were far away.

Gifford Crooks cut the forward lights and pulled his oar into his lap. Josephine did the same, and Ruthie tried not to fidget. She wrestled with her gloves regardless and finally asked in a tired, hoarse whisper, “What do we do now? Where do we go? How do we move past them?”

“We’ll have to take the long way around, and come at the big island from the west bank. It’s another mile of paddling, but it’s our only chance. Look at them up there – scanning the south and eastern shores, looking for folks who are running off, or trying to sneak out. They won’t be watching for folks coming in.”

“Why aren’t they watching the west banks?” Josephine asked.

A large spray of antiaircraft fire blew through the sky, its tracer bullets drawing a seared yellow line from the island to the clouds. The fire winged the edge of a dirigible, which made a halfhearted attempt to fire back before its thrusters flared and it scooted out of artillery range.

Gifford replied, “West side’s better fortified. That’s where the Spanish fort is. It’s mostly rubble, if you’re just looking at it during the daytime. But the bunkers are solid, and the pirates – or merchants, or whoever – use it for storage. There’s gunpowder and ammunition in the fort. It could fend off a siege for days.”

Josephine squinted at the dirigibles, and over at the small warships that had successfully squeezed past the bottleneck at Grande Terre and Grande Isle. None of them were the huge battleships that Texas often kept out in the Gulf proper. Only the lighter, faster models had made it without wrecking against the sea bottom or knocking into any of the scores of small islands and promontories that clogged the entirety of the bay.

She said, “They aren’t trying very hard.”

“What?” Gifford asked.

“They aren’t trying very hard – to take the west side, I mean. I guess they aren’t as dumb as they look. These little ships, they might be able to gang up and take the place, but it’d cost them more than it’d gain them. And the airships—” She gestured at the sky. “—if the bay boys have antiaircraft, those big hydrogen beasts are nothing but enormous targets. None of them look armored. But it’s hard to tell from here.”

“You’re right,” Gifford agreed thoughtfully. “They’re mostly transport ships. One or two armored carriers, but only the light variety. Maybe that’s all they had on hand.”

Ruthie asked, “What does that mean? I don’t understand.”

Josephine filled her in. “It means they’re surveillance ships, not warships. And there are a lotof them. Texas didn’t bring those ships to attack Barataria. They’re looking for something, not shooting at anything. They’re looking for Ganymede.”

“Ma’am, we don’t know that,” Gifford cautioned.

She turned around on her hard wood seat, and only then realized that half her behind had fallen asleep, and her ribs felt bruised from all the paddling in her unforgiving undergarments. “What else could they be looking for?”

“Pirates?” Ruthie offered.

“They already know the pirates are here – it’s the worst-kept secret in Louisiana. But Colonel Betters and Lieutenant Cardiff had the wrong idea. They thought we were smuggling the ship out in pieces, moving it down to the Gulf with pirate help.”

Ruthie asked, “Moving it through Barataria?”

“It’s a secluded spot with good docks, crawling with men who will do anything for a dollar – men who have been sneaking products in and out of the city for a hundred years. Goddamn,” she swore. “Clear out the viper’s nest with the government’s blessing, and scrounge up the Ganymedewhile you’re at it. Even if you fail at one, with money and planning, you’ve got a good chance of succeeding at the other.”

Crooks shook his head. “Are even the Texians that arrogant? To think they could uproot the bay in one strike?”

Josephine returned her gaze to the gliding lights of the searching ships in the water and in the sky, and fixed it there as she said. “They’ve done it, haven’t they? Temporarily, I’d wager. But they’ve beaten down the Lafittes in the short term, that’s for damn sure.”

“I wouldn’t write them off yet,” Gifford argued as another streak of antiaircraft fire broke the velvet blackness of the marshland midnight. “They were caught off guard, that’s all. Texas will get bored. They’ll eventually figure out Ganymedeisn’t there and wander off – or the Lafittes will safely abandon the place and restore it later.”

Josephine said, “Probably. Pirates are lone wolves, as often as not. But if you call a number of lone wolves to your aid, you wind up with quite a pack.”

And then Gifford asked, “Do you think they’d come? For the Lafittes? For Barataria?”

“They’ll come from all over the world,” she said softly. “This bay is the closest thing they have to a homeland – it is their nation, in a way – and I do not think they will let the insult stand. Not for long. Give them time.”

“Deaderick doesn’t have time,” Ruthie reminded them.

“Then we won’t wait for them. No cavalry coming but us, isn’t that right, Mr. Crooks?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said without even the faintest note of enthusiasm.

“Then let’s get paddling, shall we?” Her next questions came close on one another’s heels, as if she might get answers she wouldn’t like if she quit asking them. “He’ll be fine there, won’t he? He was fine when you left, wasn’t he?”

She began to stroke with the oar, and Gifford followed her lead. He answered so far as he was able. “Yes, ma’am, he was hanging in there. I don’t think—” He grunted as his oar stuck, and he pulled it out again. “—I don’t think the shots he took were so bad.”

Ruthie sneered. “Two bullets, not so bad.”

“There’s different kinds of being shot. Rick took his lumps, and they missed his heart. Missed his lungs, as far as we could tell. His worst trouble will be festering, if the wounds take a fever. And there’s only so much we could do about that, under circumstances like these.”

“We’ll need a doctor. A nurse. Somebody.” Josephine paddled grimly.

“We will find one. We will find somebody.” Ruthie patted Josephine’s shoulder, then wrapped her arms around herself as if the night were cold.

For two hours more they paddled, coasted, and hid between the tall clusters of waving fronds and bubbling holes where alligators hid and small fish slept. Eventually they’d circled the largest island and sneaked around to the far side where the fort was hunkered low near the narrow coastline, such as it was.

Even from the blower, with its fan long silenced, the three occupants could see that the fort’s walls were worn down, their corners rubbed into softness by the years. It looked like nothing so much as an assortment of pale stone walls, and from so far away, those walls appeared so short, a woman could step across with a lifted skirt and a tippy toe. Their height was shortened from age, yes. They were dwarfed by the latticework of pipe docks and oversized ships drifting close, and drifting away again. But they were not as short as they seemed, and they were not so fragile that they hadn’t stood a hundred years already.

“Not much of a fort,” Ruthie complained, having never seen it from the inside. Her words were muttered as low as a bullfrog’s hum.

Josephine replied in kind, keeping everything muted, lest they be discovered. “There’s more to it than you’d think. Let’s go around to the fort’s southwest corner. There’s a canal going under the wall, but you can’t see it from here. For that matter, you can barely see it when you’re right on top of it.”

“Will there be a guard? A lookout?”

“I assume,” Josephine acknowledged. “But leave him to me.”

A Texian search ship eclipsed the moon, the clouds, and the faint sparkles of stars shining through them. It moved slowly, like an oversized balloon, or that was the impression it gave on the ground. Untrue, of course. The big thing’s graceful sway belied a terrible speed, and it swung a brilliant yellow searchlight. Josephine, Ruthie, and Gifford could hear it all the way from down in the marsh – the sizzling pop and fizz of the electric filaments simmering against the mirrors that reflected and focused them.

“Hurry,” Josephine gasped, leaning harder against her oar. She was exhausted. They were all exhausted. But the big white beam was sauntering nearer, sweeping and scanning, and they were pinned on most sides by the oversized grass.

Ruthie struggled for optimism. “We’re almost there!” she whispered fiercely, spying the curved archway like a mouse hole in the fort’s southwest wall.

“They’re going to see us,” Gifford fretted. His eyes stayed on the sky, on the too-big ship hovering just out of shooting range, combing the edges around the fort. “We can’t dodge the light. We can’t outrun it!”

“Maybe we don’t have to.”

“Ma’am?” Gifford asked, lifting his eyebrows at Josephine.

“It’s not far. Another what – fifty yards? Start the engine.”

“Ma’am!” Ruthie gasped.

“You heard me. Start the engines. This blower can outmaneuver that dirigible any day of the week. We’ll make a dash for it, cross our fingers, and slide right under the wall before anyone up there has any idea what to make of it.”

“But, ma’am—,” Gifford began.

Firmly, she cut him off. “Every single moment you delay costs us time. The ship will swing around momentarily, and the light will come with it. The longer it takes them to see us, the less time they have to shoot us.”

Ruthie looked faint, but Josephine clasped a hand down on her knee. “Buck up, darling. They aren’t likely to hit us.”

“How can you be so sure, eh?”

“Because if we’re within striking range, so are they. Pull the cord, Mr. Crooks! Pull it now, or I’ll do it myself.”

He reached for the cord and gave it a yank. The engine sputtered, but did not catch. He pulled again. This time it burbled to life in a cough that rose to a roar. He threw the boat into gear as the two women simultaneously lifted the spokes up out of the water and drew their oars into their laps.

Lacking the forward momentum of a craft in motion, the little blower struggled against the saw grass, forcing past it only with difficulty at first. But as the motor drove and the diesel chugged, it pushed onward, stronger, faster, so that the grass slapped up against the sides. The women ducked down and Gifford Crooks leaned forward, one hand gripping the steering lever and the other manning the gears. He dropped them lower when the turf choked their progress, and urged them higher when the way was clearer.

The dirigible above swooned and spun, and its light swung around to hunt them. It found them within moments, but it had a hard time keeping them.

The blower dashed through the black-water muck, skimming the top and leaving a terrific trail of fetid spray and shredded leaves, grass, and cattails behind it. Every few moments, the light would catch up to them, hold them, and slip away again. They were moving too swiftly, in too stark a zigzag pattern, for any lamp above to track them for long.

Overhead, the sound of artillery came in a smattering line of pops, but if anything landed close to the blower, there was too much noise and motion for Josephine, Ruthie, or Gifford to hear it. If bullets landed, they were fired from so far away that they merely dropped into the water, and any larger shells that were incoming, only stabbed at their wake.

Josephine wished to God she’d thought to bring a flag, not that it would’ve mattered, necessarily. She had to trust that whoever was watching from the fort was aware that this small blower speeding toward the canal was not the transport of any Texians or other officials. She had to believe that the men on guard would assume they were in search of shelter, or to provide reinforcements or information, or for some mission other than sabotage.

It was either assume this or turn back. If she was right, they’d be allowed under the wall. If she wasn’t, they’d be blown out of the water before they reached it.

At night, with or without the light that beamed down from above like the angry glare of an archangel, no one would recognize her on the tiny boat. No one would know her, or hear her name even if she had time to shout it.

Soaked to the bone, she and Ruthie grasped the handholds, and each other, and kept their heads low, as if they could duck out from underneath the penetrating gaze of the light. Faster and faster their destination approached. They neared it at a breakneck speed, dodging left to right and back again, zipping around unnavigable clumps and clusters of foliage, tree stumps, and fallen masonry boulders from the old walls.

Their mouse hole destination wall grew bigger on the immediate horizon, illuminated by the swishing glances of lights from the air, and by the sometimes-flashes of tracer bullets flicking from ground to sky, sky to ground. Gifford Crooks aimed for the portal and squinted against the spray of swamp water misting into his eyes, flying off the grasses. He set his course, gunned the engine to the outside limit of what it could sustain, and gave it all the fuel the thing could manage.

Surging with a bounding leap, the blower nearly leaped off the surface of the clotted water, then slapped back against it and moaned, the swamp hissing against its undercarriage.

Ruthie prayed in French. Josephine held her breath.

And just before the craft slipped beneath the arch, Gifford cut the engine and let the blower glide forward – holding its course but slowing to jerk them all in their seats. Josephine toppled to the floor and took Ruthie with her. Gifford threw himself down on top of them, sheltering them with his own body.

The blower drifted from violent night to sudden midnight, emerging on the other side of the mouse hole into a ground-floor warren that was more mud than water. It heaved and skidded sideways up onto the closest bank, lodging itself in the mud and settling with a wet sucking sound.

The engine died.

The sudden silence left Josephine shaky; she lifted her head and pulled Ruthie close, just in time to hear the clicks of guns being made ready, and pointed in their direction. Gifford looked up, held out his hands, and said, “Fellas, kindly ignore the uniform. I’m with the bayou boys, and they’ll vouch for me. This here is—,” he started to say, gesturing at Josephine.

“Miss Early!” the nearest man gasped, and he lowered his gun. He was not a tall man, nor a particularly fearsome one in appearance, but the others deferred to him all the same, and all the guns present were soon pointing at the ground.

Though he was balding on top, around the sides and back, he had enough hair for a ponytail tied with a bit of leather. His clothes were smeared with gunpowder and soot, which had clearly become the operating uniform for everyone inside the fort. At a glance, they might have all been the same race, or the same army. The same group of burrowing resistance fighters, determined to dig in and raise hell.