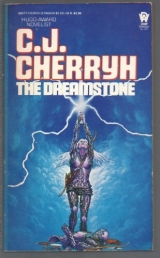

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

“Evil words for evil, but only one is true.”

“A plague on your prophecy.”

“Ill and ill.”

“Leave me.”

The Gruagach hopped down from the rock and came nearer still “Not I.”

“Will he die then?”

“Perhaps.”

Then be clear.” Hope had started up in him, a guilty desperate thing, and he seized the Gruagach by its shaggy arms and held it “If you have the Sight, then See. Tell me—tell me—was there truth in the harper? Is there hope at all? If there was hope—will there be a King again? Is it on me to serve this King?”

“Let go!” it cried. “Let go!”

“Be plain with me,” Niall said and shook it hard, for a terror made him cruel, and the creature’s eyes were wild. “Is there hope in this King?”

“He is dark,” hissed the Gruagach with a wild shake of its shaggy head, and its eyes rolled aside and fixed again on his. “O dark.”

“Who? What meaning, dark? Name me names. Will this young King live?”

The Gruagach gave a moan and suddenly bit him fiercely, so that he jerked his hand back and lost the Gruagach from his grip, holding the wounded hand to his lips. But the creature stopped and hugged itself and rocked to and fro, wild eyed, and spoke in a thin, wailing voice:

Dark the blight and dark the path and strong the chains that bind them

Fell the day that on them dawns, for doom comes swift behind them.

“What sense is that?” Niall cried. “Who are they? Do you mean myself?”

“No, no, never Cearbhallain. O Man, the Gruagach weeps for you.”

“Shall I die then?”

“All Men die.”

“A plague on you!” He sucked at his wounded hand. “What chains and where? Is it Caer Wiell you mean?”

“Stay,” it said, and fled.

He almost had the will to go. He stood on the hillside and looked down at the dale that led away toward the outgoing of the hills. But that Stayrang in his ears, and his bones ached with his running, and Caoimhin was nowhere in sight

He sank down there, and watched till sundown, but the courage for the road grew colder and colder, and his belief in it less and less.

At last a boy came running, jogging along by turns and running as if his side hurt, down in the place between the hills.

“Scaga!” Niall called, rising to his feet.

The boy stopped as if struck, and looked up, and began to run toward him, stumbling as he ran; but Niall came down to him and caught him in his arms.

“I thought you had gone,” the boy said, and never Scaga wept, but his lip quivered.

“Caoimhin is gone,” Niall said, “not I. Is supper ready?”

For a moment Scaga fought for breath. “I think so.”

So he came back with Scaga, and the snare was fast.

FOUR

The Hunting

Arafel dreamed. It was only a moment of a dream, a slipping elsewhere into memory, which she did much, into a brightness much different from the dim nights and blinding days of mortal Eald. But her time being never what the time of Men was, she had hardly time to sink to sleep again when a sound had waked her, a plaintive sound and strange.

He has come back again, she thought drowsily, no little annoyed; and then she sought and found something quite different—a fell thing had gotten in, or came close, and something bright fled ringing through her memory.

She gathered herself. The dream scattered in pieces beyond recall, but she never heeded. The wind blew a sound to her and all of Eald quivered like a spider web. She took a sword and flung her cloak about her, though she could have done more. It was carelessness and habit; it was fey ill luck, perhaps. But no one challenged Arafel; so she followed what she heard.

There was a path through Eald, up from the Caerbourne ford. It was the darkest of all ways to be taking out of Caerdale, and since she had barred it few had traveled it: brigands like the outlaw—this kind of Man might try it, the sort with eyes so dull and dead they were numb to ordinary fear and sense. Sometimes they were even fortunate and won through, if they came by day, if they moved quickly and never tarried or hunted the beasts of Eald. If they sped quickly enough then evening might see them safe away into the New Forest in the hills, or out of Eald again to cross the river.

But a runner entering by night, and this one young and wild-eyed and carrying no sword or bow, but only a dagger and a harp—this was a far rarer venturer in Eald, and all the deeper shadows chuckled and whispered in their startlement

It was the harp she had heard, this unlikely thing which jangled on his shoulder and betrayed him to all with ears to hear, in this world and the other. She marked his flight by that sound and walked straight into the way to meet him, out of the soft cool light of the elvish sun and into the colder white of his moonlight. Unhooded she came, the cloak carelessly flung back; and shadows which had grown quite bold in the Ealdwood of latter earth suddenly felt the warm breath of spring and drew aside, slinking into dark places where neither moon nor sun cast light

“Boy,” she whispered.

He started in mid-step like a wounded deer, hesitated, searching out the voice in the brambles. She stepped full into his light and felt the dank wind of mortal Eald on her face. The boy seemed more solid then, ragged and torn by thorns in his headlong flight through the wood. His clothes were better suited to some sheltered hall—they were fine wool and embroidered linen, soiled now and rent; and the harp at his shoulders had a broidered case.

She had taken little with her out of otherwhere, and yet did take: it was always in the eye which saw her. She had come as plainly as ever she had ventured into the mortal world, and leaned against the rotting trunk of a dying tree and folded her arms without a hint of threat, laying no hand now to the silver sword she wore. More, she propped one foot against a projecting root and offered him her thinnest smile, much out of the habit of smiling at all. The boy looked at her with no less apprehension for that effort, seeing, perhaps, a ragged vagabond in outlaw’s habit—or perhaps seeing more and having more reason to fear, because he did not look to be as blind as some. His hand touched a talisman at his breast and she, smiling still, touched that pale green stone which hung at her own throat, a talisman which had power to answer his.

“Now where would you be going,” she asked him, “so recklessly through the Ealdwood? To some misdeed? Some mischief?”

“Misfortune, most like.” He was out of breath. He still stared at her as if he thought her no more than moonbeams, which amused her in a distant, dreaming way. She took in all of him, the fine ruined clothes, the harp on his shoulder, so very strange a traveler on any path in all the world. She was intrigued by him as no doings of Men had yet interested her; she longed—But suddenly and far away the wind carried a baying of hounds. The boy cried out and fled away from her, breaking branches in his flight.

His quickness amazed her out of her long indolence, catching her quite by surprise, which nothing had done in long ages. “Stay!” she cried, and stepped into his path a second time, shadow-shifting through the dark and the undergrowth like some trick of moonlight. She had felt that other, darker presence; she had not forgotten, far from forgotten it, but she was light with that threat, having far more interest in this visitor than any other. He touched something forgotten in her, brought something of brightness in himself, amid the dark. “I do doubt,” she said quite casually to calm him, the while he stared at her as if his reason had fled him, “I do much doubt they’ll come this far. What is your name, boy?”

He was instantly wary of that question, staring at her with that trapped deer’s look, surely knowing the power of names to bind.

“Come,” she said reasonably. “You disturb the peace here, you trespass my forest—What name do you give me for it?”

Perhaps he would not have given his true one and perhaps he would not have stayed at all, but that she fixed him sternly with her eyes and he stammered out: “Fionn.”

“Fionn.” Fairwas apt, for he was very fair for humankind, with tangled pale hair and the first down of beard. It was a true name, holding much of him, and his heart was in his eyes. “Fionn.” She spoke it a third time softly, like a charm. “Fionn. Are you hunted, then?”

“Aye,” he said.

“By Men, is it?”

“Aye,” he said still softer.

‘To what purpose do they hunt you?”

He said nothing, but she reckoned well enough for herself.

“Come then,” she said, “come, walk with me. I think I should be seeing to this intrusion before others do.—Come, come, have no dread of me.”

She parted the brambles for him. A last moment he delayed, then did as she asked and walked after her, carefully and much loath, retracing the path on which he had fled, held by nothing but his name.

She stayed by that track for a little distance, taking mortal time for his sake, not walking the quicker ways through her own Eald. But soon she left that easiest path, finding others. The thicket which degenerated from the dark heart of Eald was an unlovely place, for the Ealdwood had once been better than it was, and there was still a ruined fairness about that wood; but these young trees they began to meet had never been other than desolate. They twisted and tangled their roots among the bones of the crumbling hills, making deceiving and thorny barriers. It was unlikely that any Man could ever have seen the ways she found, let alone track her through the night against her will—but she patiently made a way for the boy who followed her, now and again waiting, holding branches parted for him. So she took time to look about her as she went, amazed by the changes the years had wrought in this place she once had known. She saw the slow work of root and branch and ice and sun, labored hard-breathing, mortal-wise, and scratched with thorns, but strangely gloried in it, alive to the world this unexpected night, waking more and more. Ever and again she turned when she sensed faltering behind her: the boy each time caught that look of hers and came on with a fresh effort, pale and fearful as he seemed, past clinging thickets and over stones; doggedly, as if he had lost all will or hope of doing otherwise.

“I shall not leave you alone,” she said. “Take your time.”

But he never answered, not one word.

At last the woods gave them a little clear space, at the veriest edge of the New Forest. She knew very well where she was. The baying of hounds came echoing up to her out of Caerdale, from the deep valley the river cut below the heights, and below was the land of Men, with all their doings, good and ill. She thought a moment of her outlaw, of a night he sped away; a moment her thoughts ranged far and darted over all the land; and back again to this place, this time, the boy.

She stepped up onto the shelf of rock at the head of that last slope, while at her feet stretched all the great vale of the Caerbourne, a dark, tree-filled void beneath the moon. A towered heap of stones had lately risen across the vale on the hill. Men called it Caer Wiell, but that was not its true name. Men forgot, and threw down old stones and raised new. So much did the years do with the world. And only a moment ago a man had sped—or how many years?

Behind her the boy arrived, panting and struggling through the undergrowth, and dropped down to sit on the edge of that slanting stone, the harp on his shoulders echoing. His head sank on his folded arms and he wiped the sweat and the tangled pale hair from his brow. The baying, which had been still a moment, began again much nearer, and he lifted frightened eyes and clenched his hands on the rock.

Now, now he would run, having come as far as her light wish could bring him. Fear shattered the spell. He started to his feet. She leapt down and stayed him yet again with a touch of light fingers on his sweating arm.

“Here’s the limit of my woods,” she said, “and in it hounds do hunt that you could never shake from your heels, no. You’d do well to stay here by me, Fionn, indeed you would. Is it yours, that harp?”

He nodded, distracted by the hounds. His eyes turned away from her, toward that dark gulf of trees.

“Will you play for me?” she asked. She had desired this from the beginning, from the first she had felt the ringing of the harp; and the desire of it burned far more keenly than did any curiosity about Men and dogs—but one would serve the other. It was elvish curiosity; it was simplicity; it was, elvish-wise, the truest thing, and mattered most.

The boy looked back into her steady gaze as though he thought her mad; but perhaps he had given over fear, or hope, or reason. Something of all three left his eyes, and he sat down on the edge of the stone again, took the harp from his shoulders and stripped off the case.

Dark wood starred and banded with gold, it was very, very fine: there was more than mortal skill in that workmanship, and more than beauty in its tone. It sounded like a living voice when he took it into his arms. He held it close to him like something protected, and lifted a pale, still sullen face.

Then he bowed his head and played as she had bidden him, soft touches at the strings that quickly grew bolder, that waked echoes out of the depths of Caerdale and set the hounds in the distance to baying madly. The music drowned the voices, filled the air, filled her heart, and now she felt no faltering or tremor of his hands. She listened, and almost forgot which moon shone down on them, for it had been long, so very long, since the last song had been heard in the Ealdwood, and that was sung soft and elsewhere.

He surely sensed a glamor on him, in which the wind blew warmer and the trees sighed with listening. The fear passed from his eyes, and while the sweat stood on his face like jewels, it was clear, brave music that he made.

Then suddenly, with a bright ripple of the strings, the music became a defiant song, strange to her ears.

Discord crept in, the hounds’ fell voices which took the music and warped it out of tune. Arafel rose as that sound grew near. The harper’s hands fell abruptly still. There was the rush and clatter of horses in the thicket below.

Fionn himself sprang to his feet, the harp laid aside. He snatched at once at the small dagger at his belt, and Arafel flinched at the drawing of that blade, the swift, bitter taint of iron. “No,” she wished him, wished him very strongly, and stayed his hand. Unwillingly he slid the weapon back into its sheath.

Then the hounds and the riders came pouring up at them out of the darkness of the trees, a flood of dogs black and slavering and two great horses clattering among them, bearing Men with the smell of iron about them, Men glittering terribly in the moonlight. The hounds surged up the slope baying and bugling and as suddenly fell back again, making a wide circle, alternately whining and cringing and lifting their hackles at what they saw. The riders whipped them, but their horses shied and screamed under the spurs and neither horses nor hounds could be driven farther.

Arafel stood, one foot braced against the rock, and regarded this chaos of Men and beasts with cold curiosity. She found them strange, harder and wilder than the outlaws she knew; and strange too was the device on them, a wolf’s grinning head. She did not recall that emblem—or care for the manner of these visitors, less even than the outlaws.

A third rider came rattling up the slope, a large man who gave a great shout and whipped his unwilling horse farther than the other two, all the way to the crest of the hill facing the rock, and halfway up that slope advanced more Men who had followed him, no few of them with bows. The rider reined aside, out of the way. His arm lifted. The bows bent, at the harper and at her.

“ Hold,” said Arafel.

The Man’s arm did not fall: it slowly lowered. He glared at her, and she stepped lightly up onto the rock so that she need not look up so far, to this Man on his tall black horse. The beast suddenly shied under him and he spurred it and curbed it cruelly; but he gave no order to his men, as if the cowering hounds and trembling horses had finally made him see what he faced.

“Away from there!” he shouted at her, a voice fit to make the earth quake. “Away! or I daresay you need a lesson too.” And he drew his great sword and held it toward her, curbing the protesting horse.

“ Me,lessons?” Arafel stepped lightly to the ground and set her hand on the harper’s arm. “Is it on his account you set foot here and raise this noise?”

“My harper,” the lord said, “and a thief.Witch, step aside. Fire and iron can answer the likes of you.”

Now in truth she had no liking for the sword the Man wielded or for the iron-headed arrows yonder which could come speeding their way at this Man’s lightest word. She kept her hand on Fionn’s arm nonetheless, seeing well enough how he would fare with them alone. “But he’s mine, lord-of-Men. I should say that the harper’s no joy to you, or you’d not come chasing him from your land. And great joy he is to me, for long and long it is since I’ve met so pleasant a companion in the Ealdwood—Gather the harp, lad, do, and walk away now. Let me talk to this rash Man.”

“Stay!” the lord shouted; but Fionn snatched the harp into his arms and edged away.

An arrow hissed: the boy flung himself aside with a terrible clangor of the harp, and lost the harp on the slope. He might have fled, but he scrambled back for it and that was his undoing. Of a sudden there was a half-ring of arrows drawn ready and aimed at them both.

“Do not,” said Arafel plainly to the lord.

“What’s mine is mine.” The lord held his horse still, his sword outstretched before his archers, bating the signal. “Harp and harper are mine.And you’ll rue it if you think any words of yours weigh with me. I’ll have him and youfor your impudence.”

It seemed wisest then to walk away, and Arafel did so. But she turned back again in the next instant, at distance, at Fionn’s side, and only half under his moon. “I ask your Name, lord-of-Men, if you aren’t fearful of my curse.”

So she mocked him, to make him afraid before his men. “Evald of Caer Wiell,” he said back in spite of what he had seen, no hesitating, with all contempt for her. “And yours, witch?”

“Call me what you like, lord.” Never in human ages had she showed herself for what she was, but her anger rose. “And take warning, that these woods are not for human hunting and your harper is not yours anymore. Go away and be grateful. Men have Caerdale. If it does not please you, shape it until it does. The Ealdwood’s not for trespass.”

The lord gnawed at his mustaches and gripped his sword the tighter, but about him the drawn bows had begun to sag and the loosened arrows to aim at the dirt. Fear was in the bowmen’s eyes, and the riders who had come first and farthest up the slope hung back, free men and less constrained than the archers.

“You have what’s mine,” the lord insisted, though his horse fought to be away.

“And so I do. Go on, Fionn. Do go, quietly.”

“You’ve what’s mine,” the valley lord shouted. “Are you thief then, as well as witch? You owe me a price for it.”

She drew in a sharp breath and yet did not waver in or out of the shadow. It was so, if his claim was true. “Then do not name too high, lord-of-Men. I may hear you, if that will quit us. And likewise I will warn you: things of Eald are always in Eald. Wisest of all if what you ask is my leave to go.”

His eyes roved harshly about her, full of hate and yet of wariness as well. Arafel felt cold at that look, especially where it centered, above her heart, and her hand stole to that moon-green stone which hung uncloaked at her throat.

“I take leave of no witch,” said the lord. “This land is mine—and for my leave to go—The stone will be enough,” he said. “ That.”

“I have told you,” she said. “You are not wise.”

The Man showed no sign of yielding. So she drew it off, and still held it dangling on its chain, insubstantial as she was at present—for she had the measure of them and it was small. “Go, Fionn,” she bade the harper; and when he lingered yet: “ Go!” she shouted. At the last he ran, fled, raced away like a mad thing, clutching the harp to him.

And when the woods all about were still again, hushed but for the shifting and stamp of the horses on the stones and the whining complaint of the hounds, she let fall the stone. “Be paid,” she said, and walked away.

She heard the hooves racing at her back and turned to face treachery, fading even then, felt Evald’s insubstantial sword like a stab of ice into her heart. She recoiled elsewhere, bowed with the pain of it that took her breath away.

In time she could stand again, and had taken from the iron no lasting hurt. Yet it had been close: she had stepped otherwhere only narrowly in time, and the feeling of cold lingered even in the warm winds. She cast about her, found the clearing empty of Men and beasts, only trampled bracken marking the place. So he had gone with his prize.

And the boy—She went striding through the shades and shadows in greatest anxiety until she had found him, where he huddled hurt and lost in a thicket deep in Eald.

“Are you well?” she asked lightly, concealing afl concern. She dropped to her heels beside him. For a moment she feared he might be hurt more than the scratches she saw, so tightly he was bowed over the harp; but he lifted his pale face to her in shock, seeing her so noiselessly by him. “You will stay while you wish,” she said, out of a solitude so long it spanned the age of the trees about them, of a stillness so deep the leaves of them never moved. “You will harp for me.” And when he still looked at her in fear: “You’d not like the New Forest. They’ve no ear for harpers there.”

Perhaps she was too sudden with him. Perhaps it wanted time. Perhaps Men had truly forgotten what she was. But his look achieved a perilous sanity, a will to trust.

“Perhaps not,” he said.

“Then you will stay here, and be welcome. It is a rare offer. Believe me that it is.”

“What is your name, lady?”

“What do you see of me? Am I fair?”

Fionn looked swiftly at the ground, so that she reckoned he could not say the truth without offending her. And she mustered a laugh at that in the darkness.

“Then call me Feochadan,” she said. “ Thistleis one of my names and has its truth—for rough I am, and have my sting. Fm afraid it’s very much the truth you see of me.—But you’ll stay. You’ll harp for me.” This last she spoke full of earnestness.

“Yes.” He hugged the harp closer. “But I’ll not go with you, understand, any farther than this. Please don’t ask. I’ve no wish to find the years passed in a night and all the world grown old.”

“Ah.” She leaned back, crouching near him with her arms about her knees. “Then you doknow me.—But what harm could it do you for years to pass? What do you care for this age of yours? The times hardly seem kind to you. I should think you would be glad to see them pass.”

“I am a Man,” he said ever so quietly. “I serve my King. And it’s myage, isn’t it?”

It was so. She could never force him. One entered otherwhere only by wishing it. He did not wish, and that was the end of it. More, she sensed about him and in his heart a deep bitterness, the taint of iron.

She might still have fled away, deserting him in his stubbornness. She had given a price beyond all counting and yet there was retreat and some recovery, even if she spent human years in waiting. In the harper she sensed disaster. He offended her hopes. She sensed mortality and dread and all too much of humanness.

But she settled in the sinking moonlight, and watched beside him, choosing instead to stay. He leaned against the side of an aged tree, gazed at her and watched her watching him, eyes darting to the least movement in the leaves, and back again to her, who was the focus of all ancientness in the wood, of dangers to more than life. And at last for all his caution his eyes began to dim, and the whispers had power over him, the sibilance of leaves and the warmth of dreaming Eald.

FIVE

The Hunter

Fionn slept, and waked at last by sunrise, blinking and looking about him in plain fear that trees might have grown and died of old age while he slept. His eyes fixed on Arafel last of all and she laughed in elvish humor, which was gentle if sometimes cruel. She knew her own look by daylight, which was indeed as rough as the weed she had named herself. She seemed tanned and thin and hard-handed, her gray-and-green all cobweb patchwork, and only the sword stayed true. She sat plaiting her hair to a single silver braid and smiling sidelong at the harper, who gave her back a sidelong and anxious glance.

All the earth had grown warm in that morning. The sun did come here, unclouded on this day. Fionn rubbed the sleep from his eyes and opening his wallet, began looking for his breakfast.

There seemed very little in it: he shook out a bit of jerky, looked at it ruefully, then split off a bit of it with his knife and offered half his breakfast to her—so small a morsel that, halved, was not enough for a Man, and a haggard and hungry one at that.

“No,” she said. She had been offended at once by the smell of it, having no appetite for man-taint, or the flesh of any poor forest creature. But the offering of it, the desperate courtesy, had thawed her heart. She brought out food of her own store, a gift of trees and bees and whatsoever things felt no hurt at sharing. She gave him a share, and he took it with a desperate dread and hunger.

“It’s good,” he pronounced quickly and laughed a little, and finished it all. He licked the very last from his fingers, and now there was relief in his eyes, of hunger, of fear, of so many burdens. He gave a great sigh and she smiled a warmer smile than she was wont, remembrance of a brighter world.

“Play for me,” she wished him.

He played for her then, idly and softly, heart-healing songs, and slept again, for bright day in Ealdwood counseled sleep, when the sun burned its warmth through the tangled branches and brambles and the air hung still, nothing breathing, least of all the wind. Arafel drowsed too, at peace in mortal Eald for the first time since many a tree had grown. The touch of the mortal sun did that kindness for her, a benison she had all but forgotten.

But as she slept she dreamed, and there were halls in that vision, of cold gray stone.

In that dark dream she had a Man’s body, heavy and reeking of wine and ugly memories, such a dark fierceness she would gladly have fled it running if she might. She felt the hate, she felt the weight of human frame, the reeling unsteadiness of strong drink.

He had had an unwilling wife, had Evald of Caer Wiell—Meara of Dun na h-Eoin was her name; he had a small son who huddled afraid and away from him in the upstairs of this great stone keep, the while Evald drank with his sullen kinsmen and cursed the day. Evald brooded and he hated, and looked oftentimes at the empty pegs on his wall where the harp had hung. The song gnawed at him, and the shame gnawed at him, bitter as the song—for that harp came from Dun na h-Eoin, as Meara came.

Treason, it had sung once, and the murder of kings and bards. Keeping it was his victory.

So Evald sat and drank his ale and heard the echoes of that harping. And in her dream Arafel’s hand sought the moonstone on its chain and found it at his throat

She had laid a virtue on it in giving it, that he could neither lose it nor destroy it. Now she offered him better dreams and more kindly as he nodded, for it had that power. She would have given him peace and mended all that was awry in him, drawing him back and back to Eald. But he made bitter mock of any kindness, hating all that he did not comprehend.

“No,” whispered Arafel, grieving, dreaming still before that fire in Caer Wiell. She would have made the hand put the stone off that foul neck; but she had no power against the virtue she herself had given it, so far, so wrapped in humankind, while hewould not. And Evald possessed what he owned, so fiercely and with such jealousy it cramped the muscles and stifled the breath.

Most of all he hated what he did not have and could not have; and the heart of it was the harper and the respect of those about him and his lust for Dun na h-Eoin.

So she had erred, and knew it. She tried to reason within this strange, closed mind. It was impossible. The heart was almost without love, and what little it had ever been given it folded in upon itself lest what it possessed escape.

He had betrayed his King, murdered his kinsmen, and sat in a stolen hall with a wife who despised him. These were the truths which gnawed at him in his darkness, in the stone mass which was Caer Wiell.

Of these he dreamed, and clenched the stone tightly in his fist, and would never let it go: this was all he understood of power—to hold, and not let go.

“Why?” asked Arafel of Fionn that night, when the moon shed light on the Ealdwood and the land was quiet, no ill thing near them, no cloud above them. “Why does he seek you?” Her dreams had told her Evald’s truth, but she sensed another in the harper.

Fionn shrugged, his young eyes for a moment aged; and he gathered his harp against him. “This,” he said.

“You said it was yours. He called you thief. What then did you steal?”

“It is mine.” He settled it in his arms, touched the strings and brought forth melody. “It hung in his hall so long he thought it was his, and the strings were cut and dead.”

“And how did it come to him?”

Fionn rippled out a somber note and his face grew darker. “It was my father’s and his father’s before him, and they harped in Dun na h-Eoin before the Kings. It is old, this harp.”

“Ah,” she said, “yes, it is old, and one made it who knew his craft. A harp for kings. But how did it come to Evald’s keeping?”

The fair head bowed over the harp and his hands coaxed sound from it, answerless.

“I’ve given a price,” she said, “to keep him from it and from you. Will you not give back an answer?”

The sound burst into softness. “It was my father’s. Evald hanged him in Dun na h-Eoin, in the court when it burned. Because of songs my father made, for truth he sang, how men the King trusted were not what they seemed. Evald was the least of that company, not great; petty even in that great a wrong. When the King died, when Dun na h-Eoin was burning, my father harped them one last song. But he fell into their hands and so to Evald’s—dead or living, I never knew. Evald hanged him from the tree in the court and took the harp of Dun na h-Eoin for his own. He hung it on his own wall in Caer Wiell for mock of my father and the King. So it was never his.”