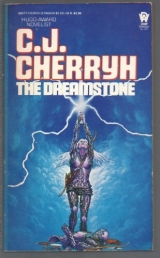

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

And Caer Wiell, to go home again, to whatever home was left—

“Niall!” he heard cry from the hill above him, a human, cracking voice, wind-thinned. “Caoimhin! Niall!”

“Scaga,” Niall said, and bis heart turned over in him. “Scaga, no.”

But the boy came running—boy: he was near a man. He came down the hill and joined them, panting as if his ribs would crack, for he had come the longer, harder way.

“Go back,” Niall said, shaking him by the arms.

“I will follow,” Scaga said reasonably, “lord.”

Niall flung his arms about him; there was nothing left to do. Caoimhin had gotten down off Banain and hugged him too.

So they went, down among the hills, Caoimhin riding mostly and they two jogging along beside, then taking turn about.

“By the river we will find them,” Caoimhin said. “There.”

SEVEN

Meara

Women grieved in Caer Wiell, a slow sort of grief, lacking substance or hope. The hunters came home by evening without their quarry and without their lord—men scratched and torn and haunted by long wandering in the wood. They drank together now in the hall, a silent, brooding crowd, whose eyes kept much to the table and to their ale. One man wept, his head bowed into his arms. He was the only one.

In her upstairs chamber Meara sat with her arm about her small son and the boy leaning his dark head against her skirts—not asleep, but drowsing sometimes in his weariness and his fright Meara sat still and silent, so that the maid, the only servant left her, dared not move or question anything.

“They brought neither home,” Meara said at last when the boy had drifted off. She looked toward the tall slit window, toward the night and still-brooding storm. “And they do not come upstairs. So they are not yet sure that he is dead.” She stroked her son’s drowsing head, looked toward young Cadhla the maid, who had pretended to be at sewing and left it now in her lap. There was stark, constant fear in Cadhla’s eyes. There was no law in Caer Wiell this night but fear. The thunder that had rumbled all the day, unnatural, cracked and shook the ancient stones. Then the rain began, at long last, a natural, driving rain. Cadhla looked toward the ceiling, a great and shaken sigh as if some long-held breath had passed her lips as if all nature had been holding its breath. The boy lifted his head. “Hush,” said Meara, “it’s only rain.”

“Does he come?” the boy asked.

“Hush, no, be still. Shall I hold you?”

He reached. Meara took him up. He was a lad of five and mostly too proud to be held, but she took him into her lap and rocked him now.

“Lady,” said Cadhla, “let me.”

“No,” said Meara, just that: “No.” So Cadhla stayed, and, looking down, pricked at ill-made stitches, flinching from the thunderclaps. The rain sluiced down the walls, a constant spatter and whisper, and the trees sighed down by the Caerbourne’s flood. Ever and again a gust whipped at the curtains and sent the lamps and candles flickering, but the child slept on. From the hall came a clattering of metal, but quiet fell again below, leaving only the rain.

“They do not come,” the lady Meara said again in the softest of voices, only for Cadhla’s ears. “But tomorrow if he has not come home again, then they will come upstairs.”

“Lady,” whispered Cadhla, “what shall we do?”

“Why, I go to the strongest,” the lady Meara said, “as I did before.” She looked down at her sleeping son. Her hand smoothed his dark cap of ham His small fist clenched the tighter on her sleeve. He was never a hearty child, Evald’s son, but small and quick to understand too much. “Hush, what can we do? What could we ever do? But if you can you must be away with him, you understand?”

“Aye,” said Cadhla softly, her blue eyes round. “I will.” But both of them understood the chances of it, Meara most of all. Gently she caressed her sleeping son, well knowing the men downstairs, that one of them would soon take ambition; and then there was no chance for the boy, no chance at all for any bearer of Evald’s blood to survive—perhaps not even past the dawn. There were Beorhthramm and the others, fell and bloody men, wild and bloody as her lord . . . and growing more drunken with every passing hour. The cups were filled again and again downstairs; and cowards gathered the courage they had lost in the woods.

But distant, from outside the window in the dark, from beneath the walls, came the hoofbeats of a running horse.

Meara lifted her head and listened through the thunder and the rush of wind and rain.

“Off the road,” whispered Cadhla. “It comes from under the walls, not the gate.”

It grew nearer still, seemed to rush beneath the window, and echoed off the stone, distinct in spite of the water’s rushing and the blowing of the leaves. A moment it lingered below, then seemed to move on again, and the thunder muttered.

“O lady,” Cadhla breathed, clutching the luckpiece at her throat, “it be faery, that”

“It would be my husband’s horse come home,” said Meara, and her eyes were far and cold. “But it could circle the hold all night and they will not unbar the gates to see, no, they are haunted men. Hush,” she said, for the boy stirred in his sleep, and she rocked him, hugged him. The hoofbeats came back again and lingered.

“Faery,” Cadhla insisted when the pacing went on and on. “O lady—”

But the hoofbeats passed away into the dark, and below, in the hall, no door was opened or closed: no one went out to see. So the sound died, and the hall grew quiet in the abating of the rain. There were not even footsteps below. The child slept exhausted in Meara’s arms, and Cadhla stopped her shivering. The curtain flapped; it had come undone in the wind which now had sunk away. Meara waved a hand toward it and with dread Cadhla got up and approached the dark window to tie it fast, then began to trim the lamps one by one, a homely act and peaceful in a hall that waited murder.

“You’ll sleep a bit,” Cadhla said when she had done. She offered her shawl. With a gesture Meara bade her spread it so, over the boy, and some peace they had after that. Cadhla fell asleep in the chair they had set against the door, her hands fallen in her lap, her head resting on her ample breast.

But Meara kept her watch, and listened to the rain which had mostly spent its fury. No tears fell from her eyes, not now. They are for yesterday, she thought to herself, and for tomorrow. Had the window been wide enough she would have thought of escape; of braiding together all the cloth they had and so letting themselves down. But it was far too narrow for any but her son. She thought desperately of waiting until those below were sunk in their cups and so trying to run with him, passing through that hall. But there was the watch below to pass, and they might be less drunken.

Perhaps, perhaps, she thought, she could win time for her son, only a little time; and wise Cadhla, faithful Cadhla might find a way for him and her, a country woman and not so lost as she. Or Cadhla might somehow get outside the gates and she might let down her son to Cadhla’s arms.

Or perhaps, after all, her lord would come home—he was safety, at least, from worse than himself. And this was the hope which turned her coward, for from the tower there was no way of escape but the hall below and the drunken men.

She might feign a mourning for her lord; but any of them who knew her would laugh at that; nor respect it even if it were true.

They might fight among themselves, that being the way of them when they had no one to stop them; and that was all the respite she could hope for, perhaps a day to save her son. But that contest only the bloodiest of them would win.

A door opened in the dark, far away and muffled. Meara heard, and shivered in the long cold, near the dawn, waking from almost-sleep with her son’s weight leaden in her arms. He comes home, she thought without thinking. He has come to the gates after all, bloody and angry.

But she doubted that. She doubted every hope of safety except Cadhla still sleeping against the door. She looked down at her son’s face. That wayward lock of hair had strayed again onto his cheek. She dared not move to brush it away, fearing to wake him. Let him sleep, she thought, o let him sleep. He will be less afraid if he can sleep.

She heard steps of more than one man coming up from the wardroom below, as one came into the hall. So, she thought with a chill up her back, it ishimself; he has come up with the gatekeeper, or waked someone below. We are safe, we are safe if only we stay still—for she knew in her heart of hearts that if the ruffians had left their lord horseless and alive in the forest, then there would be a grim reckoning for that.

Then came a ring of steel, and a cry—a clatter of metal and the dying screams of men.

“ Ah!” cried Meara and hugged her frightened son to her breast. “Hush, no, be still, be still.”

“It would be himself,” sobbed Cadhla, bolt upright, her hands before her lips. “Oh, he has come back!”

In a moment the cries and the blows and the screaming became loud. The boy shivered in Meara’s arms, and Cadhla ran to them and hugged them both and shivered along with them.

“It is not,” said Meara then, hearing the voices, and turned cold at the heart. Someone was coming up the stairs in haste. “O Cadhla, the door!”

The latch was down but that was never stout enough. Cadhla flung herself for that chair before the door to add her weight to it, but the door crashed open before her and flung the chair against the wall. Men red with blood stood there, with swords naked in their hands.

Cadhla stopped still between, making herself a barrier.

But one came last through the door, a long-faced man in a shepherd’s coat and carrying a sword, undistinguished by any badge or arms, but marked by a quiet uncommon in Caer Wiell. His hair was long and mostly grayed, his lean face seamed with scars. A grim, wide-shouldered man came in at his back, and last, a red-haired youth with a cut across his brow.

“Lady Meara,” the invader said. “Call off your defender.”

“Cadhla,” Meara said. Cadhla came aside and stood against the wall, her busy eyes traveling over all the men, her small mouth clamped tight. There was a dagger beneath her apron and her hand was not in sight.

But the tall stranger came as far as Meara’s feet and sank down on one knee, the bloody sword clasped in the crook of his arm.

“Cearbhallain,” Meara said half doubting, for the face was aged and changed.

“Meara Ceannard’s daughter. You are widowed, if that is any grief to you.”

“I do not know,” she said. Her heart was beating fast “You must tell me that.”

“This is my hold. My cousin is dead—and not at my hand, though I will not say as much for men of his below. Caer Wiell is in my hands.”

“So are we all,” she said. It was all before her, the hope of passing the gates in safety, the hopelessness of wandering after. “I may have kin in Ban.”

“Ban swings with every wind. And what then for you—the wolf’s widow? Seek shelter of An Beag? The wolf’s friends are not trustworthy. Caer Wiell is mine,I say; and I will hold it.” He put out his hand to the boy, whose fists were clenched tight in Meara’s sleeve, who flinched from the stranger’s touch. “Is he yours?”

Never yet the tears had fallen. Meara held them now, while this large and bloody hand stretched out toward her son, her babe. “He is mine,” she said. “Evald is his name. But he is mine.”

The hand lingered a moment and left him. “Evald’s heir has nothing from me; but I will treat him as a son and his mother—if she stays in Caer Wiell—will be safe while I can make her so.”

With that he rose and gave a sign to his men, only some of whom remained. “Guard this door,” he bade them. “Let no one trouble them. They are innocent.” He looked down again, a grim figure still, and holding the bloody sword still in his arm, for it could not be sheathed. “If my cousin should come home again he will have a bitter welcome. But I do not expect he will.”

“No,” said Meara, and shivered. For the first time the tears fell. “There would be no luck for him now.”

“There was no luck for him in Caer Wiell while he had it,” said Niall Cearbhallain. “But I will hold it, by my own.”

She bowed her head and wept, that being all there was to do. “Mother,” her son wailed; she held him close for comfort, and Cadhla came and held them too.

“I would not come down to the hall,” said Cearbhallain, “until we have cleansed it.” And he went away, never smiling, never once smiling. But Meara laughed, laughed as she had almost forgotten how.

“Free,” she said. “Free!—o Cadhla, he is Niall Cearbhallain, the King’s own champion! O cleansed the hall! That they have, they have. I knew him once—oh, years and years ago; and the morning has come and our night is over.”

A furtive hope had burst in Meara’s eyes, a shielded, suspecting hope, as every hope in Caer Wiell was long apt to be twisted and used for hurt. It forgot that the young harper Fionn was dead and lost; forgot an almost-love, for she was still young and the harper had touched her heart in her desolation. She forgot, forgot, and set all her future hopes on Cearbhallain. That was the nature of the niece of the former King, who had learned how to live in storms, that she knew how to find another staying place.

“Mother,” her son said—he said little always, did Evald’s son: he had learned his safety too, small that he was, which was silence, to clench his small fists on what help there was and never to let go. “Is he coming?”

“Never,” she said, “never again, little son. That man will keep us safe.”

“There was blood on him.”

“It was the blood of all the wicked in Caer Wiell. But he would never hurt us.”

So she rocked her son, and the strength left her of a sudden, so that Cadhla must catch them both. And still Meara laughed.

There was a marriage made in Caer Wiell, when the warmth of summer came. There were new faces in the hold, stark, grim men, but soft-spoken and courteous, and no few of them Meara had known in her youth, who smiled to see her, those of them who remembered to smile at all. Some folk remained from the Caer Wiell that was, but the worst had died or fled and the rest had mended what they were; and more and more came to the gates, even farmers who hoped for land—which they got as long as there was land fallow. There were some kinsmen of Niall’s, but few; there was a motley lot of folk met over the hills and in them, wild sorts and never to be crossed. There was Caoimhin, lame from the attack; and gangling Scaga; and grim, mad lord Dryw from the southern hills. But whatever the nature of them, there was law, and more, word spread abroad in what ill-luck the wolf had died, which kept the mutterings from An Beag and Caer Damh only mutterings: they had no desire to trifle with the wood and the power in it. They had felt the storm. So they were content to close the road and to pen Caer Wiell in its remoteness—as if there were anywhere to go.

So Meara wed, decked in flowers and quiet as she was always quiet, and became Niall’s lady in Caer Wiell.

And the boy Evald dogged Niall’s steps and Caoimhin’s and Scaga’s; and learned play and laughter.

“He is your son,” Niall would say to Meara, which he knew pleased her. “And my cousin, and the blood of the Kings is in him on your side.”

But at times he saw another thing, when the boy was crossed, when his temper rose. And then twice as resolutely Niall used patience with young Evald, for there were times when the boy could melt his heart, when he laughed or when, though tired, he tried to follow, matching a grown man’s steps. He would go everywhere with Niall, onto the walls, up the stairs and down, into the stables and storerooms. A word from Niall could light his eyes or cloud them, and there was no stopping such adoration.

So the boy grew, and if at times Scaga cuffed his ears when he needed it, Evald no more than frowned; it was only Niall could get tears from him. He had a pony to ride, a shaggy beast rescued from the mill, and it thrived and became a merry wicked kind of pony, jogging along by Banain on summer rides. Evald outgrew all his clothes by winter, and all his sleeves were let out, and his waists likewise, keeping Cadhla busy. And on winter nights he listened to the warriors’ tales.

But never to anything of Eald, for at any such tale Meara drew him to herself and shivered, so in this Niall forbore.

Meara bore a daughter for him, a fair blue-eyed child; and after her a sister, so he had no son, but this was, if a matter to him, still no real grief—for his luck had brought him two, Scaga, who went to broad-shouldered manhood, a dour young man who managed well the sometime defense against An Beag; who learned his soldiery of men who had fought the long hard war; and he had Evald, who grew to youth—his heir, for Scaga had no thought of ruling anything. As for Evald, Evald was innocent in his assumption that the hold was his . . . for he was fierce and prideful in his devotion—and learned to be gentle too, giving all his heart to those who gave to him—for so Niall had taught him.

So Niall had his daughters and loved them wholeheartedly, and they inherited Evald’s pony when he had outgrown it. To Evald he gave Banain’s latest foal instead.

Caoimhin died, the greatest grief that came to Niall in those happy years: it was a simple fall, his lame leg betraying him on the stairs. So Caoimhin slept in the heart of Caer Wiell, of a kind of death he had never looked to die, a peaceful one.

The trees grew again across the river. Snow fell and melted into spring, and Caer Wiell began a new tower—for, said Niall, one never knew what the times would bring. Mostly in his heart was the thought of the King, who was now toward his manhood, and that wars might come which he would never see—for age was coming on him. His hair had gone from grey to white, and one day he sent Banain away, for she was failing and he could no longer pretend the years away. He sent Scaga to lead her, and a troop of his armed men, as if the piebald mare had been some great chieftain under escort, for they had to pass the road that An Beag held: and so they did, with never a stirring from An Beag, which chose to watch more of late than act, having learned bitter lessons.

So Banain went, free up the dell.

“She ran,” Scaga reported later, his eyes alight. “She seemed doubtful a moment, and then she threw her head and lifted her tail and ran the way she could when she was young. I lost sight of her; the hills came between. But she knew the way. I do not doubt it.”

“You might have followed her yourself,” Niall said, and the tears shimmered in his eyes.

“So might you,” said Scaga. “I have my wife, my son—my home here.”

“Well, well, and Banain is home.” He set his lips. “So, well, but so am I, and so are you, that’s true. That’s true. There’s a time to let things go even when we love them.”

“Lord,” said Scaga, his strong face now much concerned. “You are out of heart about the mare. You were right. It was her time, but it’s not yet yours.”

“Caoimhin is gone. Of all the rest he had no ties; would I could have sent him.”

“He would never have left you.”

“Would never have left Caer Wiell,” Niall said. “It was the land he loved, these stones; and now he sleeps in the heart of them. I have Meara and Evald and my daughters—That foal of Banain’s will serve me, but a strong-willed horse she is. I never liked her half so well.”

“We will hunt tomorrow, lord, and change your mood.”

“I never found much joy in it, I tell you truth. It minds me of things.”

“Then we will ride and let the deer do as they like.”

“So. Yes,” said Niall, and gazed into the embers from his chair before the fire. A stone wolf’s head was above the hearth. It stared back at him. He had never taken it away.

EIGHT

The Luck of Niall Cearbhallain

The seasons passed. For long, for very long there was peace—for the young King was a rumor in the hills, and if men spoke well of him, still his day was not yet dawned. So traitors aged who had had most guilt; and true men grew old as well.

“You must do what I cannot,” Niall would say to Evald of the King; and poured his hopes into him and taught him arms, “He is your cousin,” Niall would say. “And you will set him on his throne. As I would.”

Any war in which Niall would not be foremost seemed very far to Evald, for out of his childhood this man had come, already gray, and soon white-haired, but vigorous, a storm that scoured out the hold and scoured the land of every injustice he could find; and rode at times, he or his men, to remind his enemies whose hand ruled in Caerdale. And Evald, who remembered only hurt before this man came and took him to his heart, had never thought those days would end. But end they did, at first without his realizing it—for first Caoimhin went, and then Banain, and Dryw went back to his mountains, and then Scaga took most of the border-riding on himself, while Niall sat at home. And so age came on him. So it came to a small talk in the hall, not the first such sober talk, but the deepest.

“Time will come,” said Niall, “when I am gone; and men will talk—mark you, son, I love you. But true it is you are my son by love and not by blood. The King’s own cousin: never you forget it. But Evald’s too; you are my cousin and not my son. There are those faithful who will stand by you come what may: you know their names. But men will whisper and try to bring you down, that being the way of men.”

“Then I will fight them,” said Evald. “And you will not be gone. Never speak of it.”

“That would not be wise.” Niall reached for a pitcher and poured wine into his cup, poured another for him. “So. I have a match for you in mind.”

The color fled Evald’s face and flooded it. He took the cup. He was sixteen and until that moment he had been a boy, thought like one, mostly for the hunt and games and dreams of glory in the skirmishes with An Beag; but he shared a cup with his father, rare honor, and asked quietly: “Who?”

“Dryw’s daughter.”

“Dryw!”

“His daughter, I say, not the man.”

“Dryw is—”

“Not the cheeriest of men that were my friends. But the youngest and well-gifted with sons—a fierce lot. He has one daughter, dear to his heart. His sons have one sister. And they care for their own. I could set no truer folk at your back than Dryw’s. It would ease my mind.”

“Because the man who sired me was one who killed the king.” Evald lowered his head. He had never said as much, but he had heard.

“Because you are my heir,” Niall said sternly. Then more gently: “I would not see the alliances I made slip away from you. Dryw I trust; his sons I would trust if you had a bond to them. Her name is Meredydd.”

“What does Mother say?”

“That it is the wisest thing to do.”

“What says lord Dryw?”

“He is yet to ask. First I ask my son.”

“So, well,” Evald said uncomfortably. “Yes. If it’s right.” It was unfair. There was nothing Niall could not have asked of him. For love of Niall and his mother he would have flung himself on spears, this being the direst kind of fate he had imagined for himself, warriorlike to keep Caer WielL He had never thought that there were other ways. This dismayed him more than enemies, that he had to suddenly become a man in many ways, and to be wise, and to get children of his own.

“This year,” said Niall.

“So soon.”

“I do not count my time in years.”

“Sir—”

“ ’Twould please me and please your mother. I think of her. I would see you with the strongest allies I can find—for her sake, if I am gone.”

“She will always be safe.”

“Of course she will.” Niall drank and put on a merrier face, and smiled for him, which was always like a stone that had learned to smile, so lean and hard he was.

But looking at him Evald grew afraid, perceiving for the first time that he was, after all, old; and that his riding out of the hold was growing hard for him, and his limbs were not so strong as they had been. So Banain had begun, growing thinner, bonier in the knees, until she stopped being young, and they took her to the hills. Evald believed no fables: Banain was dead; his pony had died this spring leaving his sisters heartbroken, and he cherished no illusions.

Why must things die at all? he thought. Or grow old? And he thought with terror that the curse was on him too, that now he must be a man and learn to trade in councils what men traded, and that fighting for the King when he should rise might be something less glorious and more the slow and lifelong battle it had been for Niall.

Evald’s son, they would call him, and never trust him without the claim of his mother’s blood and Cearbhallain’s allies to support him. He lost his boyhood in that thinking, and knew what, somewhere in the depth of his heart, he had always feared: that he might lose Cearbhallain himself, and slip back into the dark from which Cearbhallain had rescued him. They sang songs of Cearbhallain, of bloody Aescford, of bravery and wit and gallant deeds; and this man fostered him and shielded him and his mother, which he was old enough to understand was not the least of the gallantries of Cearbhallain. He remembered the harper, if very dimly, a golden vision and bright songs; he remembered mostly pain of his true father, blood and pain and a harsh loud voice; and one night of shining metal and hands with the blood of all those who had ever hurt his mother. She had laughed that night, and ever after smiled, and Niall had let no more blood come near her—he washed when he had come home from fighting on the border and never would see them until he and all the men with him had put off their armor and all the manner of war—because this is Caer Wiell, Niall said, not a robber hold like An Beag. And so the men about him learned to say.

But that was years ago. Before the tower rose.

It is for me, Evald thought, full of dread, and looked up at the scaffolding and the jagged stone against the sky. He builds it for me, not for himself. And then the foreboding came on him that it was the last thing Niall might do.

I do not reckon my time in years, he had said.

So month by month of summer the tower rose toward its roofing, and in all those months Niall rode but seldom, and ached much of nights: Meara tended him gently in his sometime illness, and Evald saw how the gray had touched her hair as well, and how worn she grew as his father failed. Only Niall smiled and won her smile from her. But most times Meara wore a worried look.

Month by month the messengers went back and forth with Dryw; and that grim man came, all grayed himself, a lean clamp-jawed man with young men about him who looked little more than thieves—his sons. “So, well,” Dryw said having looked Evald up and down, “I have had my spies. They report well of the boy.”

“My father speaks well of you,” Evald said, which impertinence brought the mountain lord’s cold eye back to him and gained a frown.

“Which father?” Dryw asked with Niall there to witness.

“The one who calls you friend,” Evald said sharply, “and whose opinions of men I honor.”—Which pleased Dryw and made him laugh his dry chill laugh and clap Niall on the arm.

“He is not easily at a loss,” said Dryw. And so they sent him away and arranged particulars together, Dryw and Niall, like two farmers chaffering over sheep.

So it was done, and Niall reckoned he had done the best he could. Spring, Dryw promised; Meredydd should come by spring. So Dryw and his sons went home again before the winter snows and Evald walked about with that stricken, panicked look about him that he had had that day of the talk in the hall—but it was well done, well done, Niall told himself, and so Meara said—For, said Meara, now he has kin of mine on the one side and friends of yours on the other.

“And he has Scaga,” Niall said. “He has Scaga, truest and closest,” which eased his heart to think on.

But that, with his tower, seemed enough. It seemed too wearying to bundle into heavy garments and go riding in the autumn chill; the fire was comfort. Many things which he had done of duty he left now to younger hands, and while he thought it would be splendid, as the snow fell, to saddle up and ride, to hear the hooves crunching the snow, the steady whuff of breath, and to feel the keen edge of the wind against his face—it would not be Banain under him. And to wrap up to take a ride to exercise some horse his men could do as much for seemed pointless, when his men must shelter him from any hostile meeting, when the most that they might look for was a cup of cheer at some farmhouse—but that put him all too keenly in mind of other things he missed. So he forever thought he would like to do these things, and the wanting was joy enough, not to be spoiled by doing. The best thing was his fireside, and listening to the harper who had come to his hall (but nothing like Fionn Fionnbharr, so even that joy paled). At last there was the fire’s warmth against the cold that crept into his limbs, and good food, and Meara’s kindness and his folk about him. He was fading, that was all, a gentle fading, so that he went all to gauntness.

“I shall see the spring,” he said to Meara. “That long I shall live.” What he meant was that he should see his son wed, but that seemed too grim a promise set against a wedding: and Meara shook her head and shed tears over him, scolding at him finally, which well contented him: so he smiled to please her. In all he was very tired, and thought the winter would be enough for him. His dreams when he dreamed were of that place between the hills; of orchards bare with winter; of walking knee-deep in snow to the barn and of the smell of bread when he was coming home.

He became a burden: he feared he was. He lay about much in the hall. His sons and his daughters cared for him—for his daughters too he intended marriages, young as they were, and sent messages, and arranged one for Ban and his youngest for one of Dryw’s grim sons, the best that he could do. So even in his fading his reach was far, and he took care for years to come. But Meara surprised him in her devotion and her tears—a deep surprise, for it had never seemed love on her part, only habit; for his part it was tenderness, a habit too. It was the only thing which grieved him, that he had always been scattered here and there, doing this or that for her, and for the children, and never knowing that very simple thing.