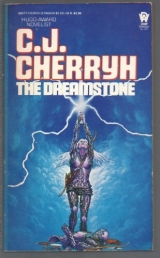

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

“Aodhan,” he named him. “Aodhan. Aodhan.” And the horse came to him, stood waiting.

“Not yet,” said Arafel, for there were others about them, human folk, who huddled against the wind, faces stark and frightened in the reflected glow, women and children and wounded men. They had no word to say to her; there were none from her to them. She walked toward the gate with Ciaran at her side and the elvish horses walked after.

“Scaga,” Ciaran said, lifting his hand toward the wall. “Scaga,” she repeated, and the old warrior looked down from the chaos on the walls, his face distraught.

“What you can do,” Scaga said, “we beg you do.”

“Beware, Scaga, what you have already asked. You have horsemen; ready them to ride with us, if they will.”

The old warrior stood still several beatings of a mortal heart. He was wise, and feared them. But he called men to him, and came down the stairs, shouted orders at boys, and commanded the horses saddled. Arafel stood still, thoughtfully took her bow from off her shoulder, and strung it. She might, she thought, go to the wall, might aid them there. But iron arrows flew in plenty, and there was time enough for that.

“Mind,” she said to Ciaran, “when you ride the shadow-ways, you are safe from iron—but you cannot strike at Men. Shift in and out of them; that is wisest”

“We can die,” he said, “—can we not?”

“No,” she said. “Not while you wear the stone. There is the fading. And there are other fates, Ciaran. Death is out there. Step into the shadow-ways and you will see him. Leave Men to me, where Men want killing. I am kinder than you know how to be. The arrows—save them: they are too dire for Men.”

“Then what shall I do?”

“Ride with me,” she said softly. “When one can do much—wisdom must guide the hand, or folly will.—Hist, they are ready.”

Boys and men brought the horses of the keep, handled, a clattering in the yard, and men ran from the defense of the walls and the gate to take them. Aodhan whickered softly and Fionnghuala saluted them too, and the mortal steeds herded together, ears pricked, nostrils straining. But Arafel walked among them, touched one and the other, named them their true names, and calmed them. “He is Whitetip,” she told a rider; “and she if Jumper. Call them true and they are yours.” The Men stared at her, but none durst question, not even Scaga, Whitetip’s rider.

She looked toward the gate, which tottered beneath the ram. Fionnghuala stepped closer to her, dipped her head and shook it impatiently.

“Do not leave me,” she bade Ciaran. “You have compelled my help. I do not compel: I ask.”

“I am by you,” he said.

“Scaga,” she said. “Bid them open the gates.” And quietly, to Ciaran: “Oftenest, Men see what they will, and cannot truly see us. Even these. Well for them they do not.”

“Do I,” he asked, “see you as you are?”

“I cannot know,” she said. “But I know you. And you had power to call my name. One must see to do that.”

He said nothing. She seized Fionnghuala’s mane and swung to her back. He mounted Aodhan, and the horse suffered it with a shiver, a flaring and quivering of the nostrils, for it was not his rider, but Ciaran knew the dream about his neck, of which Aodhan was part. Fionnghuala tossed her head, and the wind rose.

EIGHTEEN

The Battle before the Gates

The gates yielded, a groaning and splintering of wood as the braces which held them were let go and the gates grated inward. Ciaran felt the horse dance aside, light as thistledown, ears still pricked toward the enemy: no need of harness, no need of holding. Aodhan picked up his feet and began to move as effortlessly as the wind which stirred about them, and his feet came down in the boom of thunder. Lightnings cracked, making hair and mane fly. Arafel rode beside him, as the white mare, tinted with the elven moon, paced stride for stride with Aodhan.

And the enemy who had rushed against the gate saw them, mirrored terror in lightning-lit faces, a soundless, horrid screaming. They brandished weapons, and still came on, impelled by hordes behind.

“Follow me!” said Arafel, and Fionnghuala flickered into shadow as she drew the silver sword. Ciaran clung to Aodhan and the horse strode into the shadow-ways.

Horror followed. A sickness passed him near: that was iron, a blade which passed through his substance, harmless in shadow-shape. Arafel thrust at that man; she flickered out of otherwhere in the midst of that thrust and back again: the silver blade had killed. The movements of Men and mortal horses were slow, and slowing still, as the elven horses strode their gliding and fearsome way, seeming to gallop but gaining less ground than speed. Ciaran had the sword in hand, but skill failed him—he struck, and failed his mark and struck again. The stone sang in his mind and something far colder than himself seized his heart; Aodhan sprang forward feeling it, and the thunder grew. There were other shapes with them, low, loping shapes of hounds, the taller blackness of horse and rider, which raced with them. Ciaran reached for his bow, overcome with horror.

“No,” said Arafel. “Strike no blow at those.”

Death drew away, parted from them in the course, and Ciaran looked back—saw Scaga and the other riders in that same slow movement of Men, cutting their way behind them. Cloaks and hair flew in frozen swirlings, with lightning flashes. Arafel called to him and the elven horses lengthened stride, began to move forward as well as swifter. Men passed by them, faster and faster, shadows through which they could move. Iron shivered past them with pain and poison, and the horses shied farther into otherwhere, flickered out again enough to see their way.

We are phantoms on the earth, Ciaran thought, and knew not which heritage wemeant—for between those flickerings of otherwhere, like lightning-strokes, there was no army, only murky day, a strange placid landscape void of farms and wars and Men.

Yet not deserted. A horn sounded, braying, and came small folk scurrying from the hooves of the elven steeds—some fair and some foul, some direly misshapen. A weapon glanced from Ciaran’s mail, and there was no fleeing. The thunder cracked and the horses leaped forward. Ciaran struck with the sword while it profited, saw Arafel herself beset by a tide of shadows which poured out of the thickening air. She vanished and he thought her slain, but the shadows poured after her into that nothingness.

“Go,” he cried at Aodhan, and the horse leaped, following Arafel into mortal daylight. The shadows had not come through, or they hid, or transformed themselves. Arafel slew Men, a dire dream in which Ciaran’s heart was chilled . . . I am of them, his heart cried; but another mind rose up in him, flowing into his limbs and his hands.

Give over, give over, the stone sang in his heart, showing him his helplessness to wield these weapons.

He fought that voice, that one who strove to live, to come back. Aodhan ceased to obey him, raced wildly, while the wind grew and grew, while nightmares passed on either side. An anger rose in him at these ill-shapen things, these shadows that twisted into vision, the prickling of old hostility.

“Liosliath!” he heard them shout in rage; and the anger grew in him, lifted his arm, swelled in his heart. He shouted—he knew not what he cried. Aodhan leapt under him willingly, bore him along while his hands strung the elvish bow and he gathered up an arrow. The air swirled with storm: the arrow flew, ice-tipped, feathered with light A horror shrieked and fled, and others coursed the winds. There was a light by him, which became Fionnghuala and her rider, and he saw Arafel’s face calm and terrible as she sent shafts winging after his. Men ceased to matter. They were nothing. This was the war, these the enemy, old as earth, as they were old. Shapes fled before them, turning sometimes to strike and suffer wounds.

Suddenly they were alone, in a place gone gray and full of mists—They are fled, fled, the dream sang to him; and elsewhere, wherever he looked, was an iron-poisoned hush.

“Come,” said Arafel, and shadow-shifted to a bloody and littered field. Rain came down and failed to reach them, pocked bloody puddles in the mire instead, drenched the broken human bodies and the shattered spears. They were in the midst of the field, with both sides drawn back for breath. Ciaran turned Aodhan and beheld Caer Wiell, with its men ranged before it afoot, the dozen riders still remaining to them standing huddled to the fore.

It was pause, not victory. It was regrouping, while the sky poured out its tears.

Another rider came treading above the mire of the center of the battlefield. He was a shape like a fragment of night, with his robes blowing in a wind counter of the wind which blew in the mortal realm. Lord Death stopped before them, leaned seemingly on the withers of the shadow-horse, and Ciaran shuddered, for in that shadow steed’s head there was a pale hint of naked bone when the lightnings flashed.

“You are mad,” said Death. “Go back. Cease this.”

“I am bound,” said Arafel. “They have invoked my aid.”

Death straightened, and lifted a black sleeve toward the distant lines of the enemy. “ Theyare there, come from under the hills to aid them. Do you not know? There are powers which have come to align with them.”

“They would do so. But we are bound.”

“There are my brother gods,” said Death. “I bear you word from them; Withdraw, before worse is loosed.”

“Let them stay away,” said Arafel. “Enough is amiss here.”

“Go back,” Death whispered. “If the Daoine Sidhe had all left this land, these fell things would never have come again.”

“Because I have never gone away, dear youth—they have stayed to their hidings.” She laughed and the shadow horse trembled. “Do you know nowwhat watch I stand in Eald?”

Death and his horse stood still, bereft of answers. Ciaran gazed at the blackness, and Aodhan shifted and stamped, for things moved underfoot, and forces gathered.

“I do not bid you,” Ciaran said to Arafel, although it was effort. “I know what has to be. I bound you to this. I release you. Give us over to Death, us and them, only so this ends.”

Arafel gazed at him, and his skin prickled, for the lightnings stirred. “It is Men who lend them power,” she said. “And your sight is truer than it was.—We are held to battle here on this field until the army yonder bids their own allies go back.”

“And they who are winning—or losing—will not.”

“That is so. When your mortal enemy has won, then their new allies will only be the stronger. They will go on, those powers; they will gather forces; they will sweep over all the world. Do you comprehend now, Man my cousin?”

“Forgive me,” Ciaran whispered.

“It is heartsease you ask. I give you that. And I confess I had hope of more strength than we have in Caer Wiell. If we might rob the enemy of lives and human hands . . . but we have not strength enough.”

“You have power unused,” said Death. “Use it! Will you let them all break forth?”

“The cost of that too you know.”

“Our need is now.”

“That sacrifice will not kill them, only drive them for now. And what then, Lord Death? What in a hundred lifetimes of Men—when they go unwatched? Yon have no power over them, no more than over me. There no hope that way. No, I will tell you what you must do: stay your hand from Caer Wiell. Our forces are too diminished as it is.”

“I cannot,” said Death, bowing his head. “I too am bound to what I do.”

“My King,” said Ciaran, “will come here, if only we can hold.”

“Your King delays overlong,” Arafel said quietly. “Wiser had you bound me to his aid, not to doomed Caer Wiell’s. As it is, we are bound to serve and fall. And the cost of that fall you do not guess even yet.”

“There was a battle,” said Death, “a day ago. Trust me, that I know. There are still skirmishes; and that force is well-occupied in the hills, Man. Have no hope of them. This enemy has engaged them too, at the pass of Caerdale; and all your King’s strength cannot rout the enemy from those heights.”

Ciaran listened. There seemed a gleam within that dark hood. There began a beating that was his heart, or Arafel’s, or both. He laid a hand upon the stone at his throat, heard a whisper from it, felt an elvish presence that found courage to laugh at the thought that came into his mind; and Aodhan shifted to move at once.

“No,” Arafel forbade him, but a light was in her eyes. “Wise you are, but that is no road for you, o Man. Yours to hold here. Where it serves Caer Wiell, Iam free to ride.”

“His human allies will all fall and the enemy will take him,” Death said. His darkness became a nimbus about him. “I shall depart this field with all my forces. That much I can do.”

“Go,” said Arafel.

Death faded. There was only the rain, and then that stopped.

Arafel spoke to Fionnghuala. The white mare began to run. Aodhan whinnied after her, and pawed the ground, but stood fast.

And across the field the enemy began to gather their line.

Ciaran shivered. Beware, a voice in him whispered: you are only seeing Men. Others are closer.

“Liosliath,” he said, holding up the stone, and shuddered, surrendering. “I shall stop being. Wake. Wake, Liosliath. It is you they need now. Wake! your enemies are here!”

Cold fire spread from the stone. It frightened him, the power which spread through his limbs and the pride which drew breath and laughed, despising Men.

Aodhan wheeled then, and sped with long strides toward the battered lines of Caer Wiell, to pace delicately along before them. He saw Scaga’s face, marred with a bloody slash; saw this fearless man give ground from him, saw others flinch. He flickered into otherwhere and saw the enemy gathered like a tide. He drew an arrow from his quiver and fired, saw the icy point lodge deep in a shadow which faded in torment

And with the stone he drew on Eald, cast a glamor over all the force at his back, sheening them all in silver.

“Come,” he called to them, and not he: the elf prince, who drew his sword and clapped his heels to Aodhan, the prince who knew well how to fence with iron, nothing reckoning the poisoned pain which whipped through his body when it must. Faster and faster Aodhan sped, and slower and slower the Men, while he brought the flickering elvish sword out of otherwhere, lodged in human flesh—gone again before human weapon could strike.

Yet none died. Enemies weakened, and human weapons hewed them ghastly wounds, and folk of Caer Wiell were spitted in turn, and did not die, but kept hewing others, so long as they had limbs which would move.

There was a wailing on the wind, a darkness. He gathered strength against it and lightnings flashed on monstrous shapes. Blows rained against the silver mail; in rage he swept against them, wounded them, and time and time again Aodhan dropped into the mortal world, until some of the dire things followed him there, and undying Men stared in fear.

One of the Men was Scaga, whose anguished look Ciaran knew, who still held his sword, standing unhorsed in the mud. Then Ciaran’s heart was moved to pity, and he would have taken the old warrior up, but Liosliath was stronger, and Aodhan swept him on, skimming the ground with thunder. The Caerbourne down the hill flowed with blood. Saplings on the banks were trampled. He used his sword against Men wherever their ranks tried to stand, and herded them and hurt them, though they would not die. The light about him began to grow paler and brighter, for human sun was sinking into twilight, and elven sun was rising.

Then the dark things drew power more than they had before, thrusting maimed human folk forward to press against maimed Caer Wiell.

And now he was pressed back and back, for the enemy was in all places, and on all sides, converging on the ruined gate, and rending those defenders who lagged in their retreat.

A Man stood by him, at Aodhan’s shoulder: Scaga. The old warrior shouted orders to his men and from the walls of Caer Wiell arrows flew, iron which the creatures hated as much as he. Some writhed in pain. Others crept up against the walls of the hold, and tore at the very stone.

And a wind grew in the east, and thunder.

“Arafel!” he cried.

She was there. He flickered into otherwhere and saw a light among the mists of the faded lands, with shadows rearing up between, caught and desperate. He held the gate against them, though his arm grew tired and Aodhan trembled beneath him. There was a thunder in the earth as well, and more and more human attackers added force to those who had come before. But a cry of dismay went up at the far side of that living tide, human screams and battle cries.

“Liosliath!” the call came down the wind, and he saw the flickering of the white mare and the gleam of Arafel’s sword. Aodhan gathered himself and began to move, striding faster and faster.

And suddenly a shadow was beside him, a void shaped like horse and rider, and shapes like coursing hounds. Other dark riders had joined them, blacknesses as great as Death; and some who ran afoot, some like Men and some horned like stags.

Fionnghuala shone in the murk, and her rider no less than she: a pale and terrible gleaming, her hair astream on the wind. “Liosliath!” Arafel hailed him, and he reached out a hand as bright, caught hers across the gap, a joy which burned and died, because of the dire things about them.

Armies clashed in the dark and the storm, and that noise was far from them. Dark things leapt and attacked, slaying and being slain, and wounded shapes climbed the winds. Lord Death lifted the likeness of a horn and sounded it, and the clouds increased as the dark horse began to move; Aodhan paced the dark rider, and Fionnghuala joined him. Side by side with Death they rode, and the dogs bayed, coursing more and more rapidly through the air. They strode above the ground, and mounted the skirling winds. Aodhan threw his head and shook himself and Arafel circled Fionnghuala out and back again, hastening something fell and fugitive toward the dogs. Clouds tattered beneath the hooves, and the thunders rolled. The horn sounded yet again, and more and more riders joined them, bearing banners like black cloud. Armored Men, with darkened eyes set ahead upon the quarry, and lances agleam in their hands, rode on horses with eyes as dead as theirs. The slain had gathered to hunt the newly dead. Ciaran looked, and the Man in him shuddered, for he knew some of these faces, and he had loved no few of them. He saw a cousin there; and a childhood friend, and another rider on a horse with a white-tipped ear—“Scaga!” he called, but the rider coursed past, eyes dark, unheeding; and many a man of Caer Wiell followed after. The last turned and beckoned to him.

“Liosliath!” Arafel rebuked him. She held out her hand to him. Ciaran came, yielded to the elf prince, and Aodhan ran his gliding pace across the clouds, while the shadows fled.

They two turned back alone then, and rode the field in the human world, but the battle was done. Dark shapes slunk aside where they passed, sought refuge elsewhere, and vanished.

Men gathered at the gates of Caer Wiell, atop the hill. They rode quietly now, covering ground, a rush of wind about them, and had their weapons sheathed.

Then Arafel stopped, sat still on Fionnghuala, gazing toward the gates. “I am free,” she said. “ ’Tis done.”

“Let us ride nearer,” he begged her, for Donn had come riding in with lord Evald and the King’s army; and there were the folk inside Caer Wiell. He ached to know how those he loved had fared.

“Would you see them?” Arafel asked him. “Aye, I do understand the bonds of kinship. Go.”

She would not come inside the walls. He knew her pride, and ached for that as well. But Aodhan felt his will to go, and moved.

Men gave way before him, with fear on their faces. And when he had come as far as the gate, he saw lord Evald’s banner, and Evald of Caer Wiell himself standing near it, giving orders to his men. Evald stopped and stared at him. And there kneeling by Evald’s feet was Beorc, Scaga’s son, who held Scaga’s maimed and muddy body in his arms and mourned.

“He fought more than well,” Ciaran said. Beorc looked up, and grief in his eyes became dread at what he saw. The look pained Ciaran like the iron, which ached more and more in the air about him, a taint in which it grew hard to breathe. Aodhan fretted to be away, and Ciaran rode farther, within the ruined gates, sought his father and Donnchadh and the moon banner of his own Caer Donn. Elf-sight found them quickly, and he stopped Aodhan by them in the swirl of Men in the courtyard.

They looked up at a strange rider and did not know him—surely they failed to recognize him, or they would never have had such a look of dread at the sight of him. He rode away from them, and Men shrank from his path in the crowded yard. “Stay,” he bade Aodhan, slid down and walked among the Men, among his own, past cousins of his, seeing everywhere that look he dreaded.

He moved elsewhere, a reaching of the heart, a shifting, and found himself in the stone hall of Caer Wiell, by the fireside, where Lady Meredydd and Branwyn stood. Their eyes showed no less fear than the others had.

“They are well,” he said, holding the stone at his heart to ease the ache in it. “Your lord is home. You are safe. But Scaga is dead.”

He wept in telling it, not having wished to weep, and began to fade. But Branwyn called his name and held him by it. She tried to come to him, a mortal yearning. He reached and took her hand to help her, but she could not come the way he could. He kissed her fingers, and kissed her brow, and stayed a time in the room with them.

Lord Evald came, and the King with him. To the King, Ciaran knelt, while Laochailan’s young eyes regarded him with that dread others turned on him.

“Welcome sight,” the King he had loved said of him; but with the lips, not with the heart. And Evald, lord Evald, who was Eald’s near and knowing neighbor, gave him a look as bleak and unwelcoming—then came and offered him an embrace.

No other human dared, not his own father or brother, when they had come up the stairs into the hall, all clattering with armor. “Ciaran,” his father said, and gazed on him with a bleak, hag-ridden stare. Donnchadh started a step toward him, but his father held his arm and prevented him. Then Donnchadh’s face became like a stranger’s to him, grim and mournful.

They have always known, Ciaran thought, both of them have always known what is in our blood. He recalled the elvish moon which had been Caer Donn’s banner for years out of memory, and was heartstricken at such a look as Donnchadh gave him.

“We are going back,” his father told the King then without looking at him, as if he had not been there. “We have our own cares, too long neglected.”

“Go,” the King bade him; so his father and his brother went their way from the hall, not to linger long near Eald, and never looked back.

Ciaran stood wounded, looked last at Branwyn, who looked at him, and in his pain he wished himself away, in the cold air, in the mist, the deserted shadow-ways.

He came back into the mortal night in the courtyard after some time had passed, where all was quieter than it had been.

He walked outside the riven gates, where the horror of the field was honest and undiminished. “Aodhan,” he said quietly, and a wind gusted as the horse moved out of the night toward him, slow peals of thunder, a blazing like the noon of elvish sun. He stroked the white neck and thought of his home in the hills, at Caer Donn. He might go there, might—once—go there, greet his mother and his kin, see the things he had known, bring them word days before his father and Donnchadh and the men could come and tell them—before that place was closed to him forever, before—so many things. Aodhan could carry him.

He touched the stone at his throat. “Arafel,” he said.

It was another presence which came to him instead, which touched his heart far more gently than it had ever done, with elvish brightness. There was pride—always that; but this time the touch was warm. “Man,” it whispered; and there was the roar of the sea and the cries of gulls. “ Man.”

Only that he said, the elven prince, and it sufficed.

NINETEEN

The End of It All

He came, but not alone, and that surprised her—in plain good clothes, and with Branwyn tramping along with him through the brambles, her golden hair tangled with twigs. He wore the sword and carried the bow and a pack which clearly burdened him. She watched them, and would have reached out to help them, but she sensed the fear in Branwyn, and could not have helped, no more than he could: Branwyn was doomed to the thorns.

They reached the dancing-ring. He called her in his mind, and she came, smiling sadly at the pain in his eyes, and looked then at Branwyn, who managed to look back at her.

“I have brought Aodhan back,” Ciaran said.

“Swiftest to have ridden,” said Arafel.

“Branwyn tried.”

“Ah,” she said in pity, and again met Branwyn’s blue eyes, “You might have.”

Fear looked back at her, but something like the child struggled behind it. “I wanted to.”

“That is much,” said Arafel.

A wind had risen. She sensed Aodhan near, but it was Ciaran who had the summoning of him. Ciaran held out a hand, and the horse stepped into mortal sunlight, aglow with the elvish moon. Small thunders rumbled in the glade, and lightnings flickered. Ciaran stroked Aodhan’s neck, and whispered his name and bade him go. The thunder clapped and the horse was gone, that swiftly, and perhaps something of Ciaran’s heart went with him; he had that look.

Then Ciaran knelt down and unbound the pack which he had brought, and took the sword and bow and laid them atop it all the shining armor at her feet.

“Thank you,” Arafel said, and the gifts faded.

“I thank you,” Ciaran said. “I must thank you. But—do you understand?—I have carried them as far as I can. I have seen things—I shall always see them. They are enough.”

“I know,” she said.

He rose, and reached last for the chain about his neck.

“No,”’she said. “That, you must keep.”

“I cannot,” he said. He drew it off, and offered it to her hands, his own hands trembling.

“It is your protection.”

“Take it.”

“And Branwyn’s too. Do you even hope to get from out this forest without it? Would you see her hunted too?”

That struck deep. Ciaran’s hands fell; but Branwyn took his arm.

“I knew that too,” said Branwyn, and there was more of sense in her blue eyes than there had ever been. “But I am here. And we will walk out again.”

“Please,” Ciaran said, offering the stone yet again. “I am a Man, and when he comes, that is the way of Men, is it not? But if I keep this, there is no hope for me.”

Arafel took it then, unwilling, and her lips parted in shock at the strength that had come to it, and the presence in it which was indeed almost beyond bearing.

“Ah,” she said, folding it to her heart. She looked on him with tears. “You have given me a gift, o Man. And now there is nothing you have left me to give you.”

“A blessing,” he said, “for us. That I will take.”

“Few Men have ever asked it of the Daoine Sidhe.”

“I ask.”

She kissed him then, and kissed Branwyn. “Go,” she said.

They went, hand in hand, and she walked behind them, the shadow-ways, unseen. They had trouble in the going, took scratches of the thorns, and climbed high places and limped on unexpected stones; shadows hissed at them, but fled quickly when she bade them gone.

And at last it was New Forest, and Arafel stood upon the flat rock and watched them down the slope, toward the Caerbourne, and Caer Wiell.

A blackness settled near her. She frowned at it.

“Give them a little,” she asked. “Only a little time.”

“We were allies,” Death said. “Should I have so short a memory? I shall wait. As for Branwyn—she was always mine.”

Again she frowned.

“I have another face,” he said.

She drew herself up and laid a hand on her sword. “Beware of me, Lord Death; I know your name; and the day I see you as you are, you are yourself in peril. Do not tempt me.”

“You have asked a favor,” he said.

“Aye,” she said more softly, anger fallen. “That I have.”

“He may come here if he wills; and she may. He will die abed, years hence. That, I give to him.”

“Then I forgive you,” she said, “other things.”

She left him then, and walked her own way, from Airgiod’s quiet rim, to the moonlit grove.

Fionnghuala was there, and Aodhan. “Go,” she bade them. “You are free.”

They did not go; and they were free to choose that too. They stayed near, and the grove breathed with wind and memories.

“Liosliath,” she said, holding the stone near her heart.

He was aware. There wasanother place but this. She held it close and walked amid the silver trees.

Eald was smaller. But it had held. She found that place at the edge of Eald, hers and not quite hers, and the Gruagach scampered into hiding, remembering ancient quarrels—but he fared well, and so did all he cared for. The fields were safe. She preferred the earth no iron had delved, the lands shadowed with her trees—but she took care now of lands far wider than Eald, so that the lands of Men had rarely seen such a year, in which no planting failed. It cost her. She did all she could to mend what war had done, and stretched her care as far as it could go. Long ago she had chosen this woods and kept it—but now it had neighbors she valued, with special poignancy, that they were brief and brave and given to doing as they would. She had never known why she watched, except for pride, not to yield forever what once the Sidhe had been; but now it was for love.

Yet one day, one day she almost despaired, so much of Eald she had given away. She came for comfort to that heart of her wood and walked there listening to the stones, her head bowed in a weariness almost too much to bear.

So she found it, a tiny thing unlooked for at her feet. A branch, she thought, had fallen from the silver trees, which had never happened in any wind that blew—so, she thought as she bent down by it, Eald had at last begun to die, from the heart outward.

Then she cast herself to her knees in wonder—for the sprig was rooted in the ground, thrusting up from the earth with silver leaves all delicately veined, the first new life in Eald since the dimming of the world.