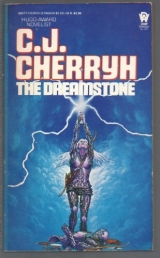

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

Scaga came up, pale and sick from an arrow which had pierced his arm and drawn a great deal of blood. From him Ciaran turned his face, and stared into the embers as he leaned against the stones of the fireplace. The ladies sat; servants brought bread and wine and cold meat.

Ciaran came to table and sat down, staring at what was before him and not at the women, nor at the harper, who had fought that day; nor at Scaga, at him least of all. The servants served them, but no one touched the food.

“It is his wound,” Branwyn said suddenly, out of the silence. “He is ill.”

“He claims to have run through enemies and scaled our wall,” Scaga said. “He gives us fair advice. But who is he, truly? How far did he run? And what manner of man have we taken among us, when our lives rely on a gate staying shut?”

Ciaran looked up and met Scaga’s eyes. “I am of Caer Donn,” he said. “We serve the same King.”

Scaga stared at him, and no one moved.

“It is his wound,” Branwyn said again. He was grateful for it.

“We have seen no wound,” said Scaga.

“Would you?” Ciaran asked, for he had no lack of scars. He put on a face of anger, but it was shame that gnawed at him. “We can go into the guardroom, if you like. We can speak of it there, if you like.”

“Scaga,” Branwyn reproved the old warrior, but Lady Meredydd put a hand upon her daughter’s, silencing her. And Scaga put himself on his feet. Ciaran stood, prepared to go down with him, but Scaga beckoned a page.

“Sword,” Scaga said. The boy brought it from the doorway. Ciaran stood still, not to be made a coward in their eyes. Branwyn had risen to her feet, and Lady Meredydd and the others, one after the other.

“I would see you hold a sword,” Scaga said. “Mine will do. ’Tis good true iron.”

Ciaran said nothing. His heart shrank within him and the stone already pained him. He looked into the old warrior’s eyes, knowing the man had seen more than the others had. Scaga unsheathed the sword and offered it toward his hands; he reached for it, took the naked blade in his palms, and tried to keep the anguish from his face. He could not. He offered it back, not to dishonor the blade by flinging it, and Scaga took it gravely. There was a profound silence in the room.

“We are deceived,” Scaga said, his deep voice slow and sad. “You brought us fair words. But gifts of your sort do not come without cost.”

There was weeping. He saw the source of it, which was Branwyn, who suddenly tore herself from her mother’s arms and rushed from the hall. That wounded as much as the iron.

“I told you truth,” Ciaran said.

There was silence.

“The King,” Ciaran said, “will come here. I am not your enemy.”

“We have lived too long next the old forest,” said the Lady Meredydd. “I charge you tell me truth. Is my lord still alive?”

“I swear to you, lady, I had his ring from his own hand, and he was alive and well.”

“By what do the fair folk swear?”

He had no answer.

“What shall we do with him?” Scaga asked. “Lady? Iron would hold him. But it would be cruel.”

Meredydd shook her head. “Perhaps he has told the truth. It is all the hope we have, it it not? And we need no more enemies than we have. Let him do as he wills, but guard him.”

Ciaran bowed his head, grateful at least for this. He did not look at Scaga, nor at the others, only at the lady Meredydd. Since she had nothing more to say to him, he walked quietly from the hall and upstairs, to imprison himself in the room they had given him, where he was spared the accusation of their eyes.

Dark had fallen. There was no lamp burning in the room, nor did he reckon that any servant would come to him tonight. He closed the door behind him, gazed at the window through a haze of tears. The night was bright, framed in stone.

Branwyn wept somewhere, betrayed. The joy he had brought them all was gone. They expected now to die. He shut his eyes, seeing his own family, the pain he was sure to bring them. Shame, and grief more piercing than shame, that they would forever know what they were and distrust their own natures.

He sat down on the bed in the dark, and unlaced his collar, drew forth the stone and held it in his hands.

SIXTEEN

The Paths of Eald

“Arafel,” he whispered, “help us.” But no answer came, and Ciaran had hoped for none. It was doubt, perhaps, which robbed him. He felt a pain in his heart, pain in all his joints, as if the poison of the iron he had touched had gone inward. Perhaps it had more than driven Arafel away; perhaps it had wounded her more than he had known. There was silence, where once her voice would have come whispering to him, and he was afraid.

The stone was power. She had promised so. To cast it off, seek a death in battle . . . he thought of this, foreknowing that he would see before his death what others could not see, and know it when it came. It seemed a small-hearted thing now, though lonely; a selfish thing, to perish to no avail, and to take the hope of Caer Wiell with him once for all. Power was for using in such straits as he had set them in, if he but knew how.

And what had the stone ever done, but link him to Eald? Fare back, Arafel had wished him.

He began, holding the stone between his hands. He rose and slipped his mind toward the green fair world . . . saw gray brightness, and moved into it.

There was nothing here. He tried to recall the way he had come with Arafel’s leading. He thought that it lay before him in the mist. A certain sense of his heart said so, and he trusted that sense, which he had denied before.

Liosliath, he thought, wishing now for the memories of that grim elf, but nothing came to him. It was, perhaps, the taint of iron. Panic swept on him like a flood of water. He wavered out of the mist and blinked in dismay, for he stood on the dark slope of the hill, outside the walls of Caer Wiell.

In panic he reached for the mist again, and ran into it, ran, with all his strength, but very quickly he was lost indeed, and he was not sure that he had taken the right course in the beginning. He thought that he could see trees in the grayness, but they were not straight and fair, but twisted shapes, and the mist darkened.

Shadows were with him, loping along in dreamlike slowness. He could not see them well, but he heard the crash of brush, the beat of hooves, slow and strange. A stag coursed the mist, but it was black, and lost itself in the grayness. A bird flew past, baleful-eyed, and black as the stag. It called at him and flew on. He ran the more, panting, and at times his feet seemed to lose their purchase and to stride lower than he wished. Hounds bayed, striking terror into his flesh, and his wound grew into an ache, and to agony. He heard the beat of heavier hooves, and the winding of a horn.

Something tattered swept by him, wailing. He stumbled away from it and shuddered against another shadow, saw trees taking tortured shape. The way was darker and darker, agreeing with mortal night, as the elven-wood never had. He was possessed of sudden terror, that he had fled the wrong way altogether, that he was driven and harried where the enemy would be, toward a place where the stone had no power to save him. A wind blew which did not scatter the mist, but chilled him to the bone.

“Arafel!” he cried, having no hope in silence. “Arafel!”

A shadow loomed ahead of him. He flung himself aside, but it caught at him, and the stone warmed at his heart.

“Names are power,” she said. “But you must use commands three times.”

He caught her hand and held it, shut his eyes, for a rush of shadows passed, and the Huntsman was among them. He thought that sight would scar him forever.

And the chill left him. He opened his eyes and they were walking through the mist into brightness, into sunlight, of green forest and meadows with pale flowers. He sank down on the grass, out of strength, and Arafel sat by him, gravely watching until he should have caught his breath.

“You are braver than wise,” she said.

“I need your help,” he said. “ Theyneed you.”

“ They.” She flung herself to her feet, and indignation trembled in her voice. “Their wars are their own. You have seen. You have seen your choices. You have come back of your own will. Do you not know now how much we have to do with Men?”

He found no arguments. There was a grayness upon him like the grief of the fair folk themselves, when the world no longer suited them, nor they the world.

Her anger stilled. He felt it die from the stone. She knelt down by him and touched his face, touched him heart, which was still cold with the memory of the dogs.

“This,” she said, touching the stone, “and iron—cannot bear one another. You know that now. You are wiser than you were. And when you are wiser still, you will know that they—have no part or peace with you.”

“I have dreamed,” he said, “and I know what once you were. And I ask your help.– Arafel, Arafel– Arafel, I ask your help for Caer Wiell.”

Her face grew cold, and still. “Too wise,” she said. “Beware such invocations.”

“Then take back your gift,” he said. “There is no heart in it.”

“It isour heart,” she said, and walked away.

He rose, looked about him, at hares which sat solemnly beneath a white tree. He despaired, and shook his head, and would have cast off the stone, but it was all his hope of return to his own night. He had walked it once; he began to walk it again, beyond the silver trees, farther and farther into the mist, for he sighted the direction true, and for whatever reason, the fear had gone.

His step never faltered, not in the direst and strangest of the mist. Trees came clear to him, and the very way to the room showed itself. He saw it, a black cell before him in the grayness. He entered it, and found walls about him once more.

He sat still through the night. There were no dreams. He slept a time and found the sun coming up, washed himself and dressed and came out into the hall, strangely numb of terrors, even when he saw Scaga’s man guarding the hall, having watched him. He came down into the hall where others gathered, and silence fell.

“Is there place for me?” a voice asked softly. He looked. It was Arafel.

Others had risen from the table, a scraping of chairs and benches. Branwyn stared, her hands to her cheeks. Scaga laid hand to his sword, but no one drew. Arafel stood still, in forester’s garments much mended and much faded. A sword hung at her side. Her pale hair was drawn back. She looked like a tall, slim boy.

“Long since I was here,” she said in their silence. Somewhere on the walls alarms were sounding, summoning them to the attack. No one yet moved. “I am bidden aid you,” she said. “I ask—do you wish that aid? Bid me aid you; or bid me go.”

“We dare not take such help,” said Meredydd.

“It is dangerous,” said the harper.

“It is,” said Arafel.

“Arafel,” Ciaran said. “What danger?”

She turned her pale eyes on him. “The Daoine Sidhe had other enemies. There are things more than you see. Long and long it is since wars have reached into Eald.”

“We die without your help,” said Meredydd. “If help it is.”

“Aye,” said Arafel, “that might be true.”

“Then help us,” said Meredydd.

“Ask cost,” said Scaga.

“ ’Tis late for that,” Arafel said softly. “Hist, do you not hear the alarms?”

“What costs?” Scaga said again.

“I am not of the small folk,” Arafel said in measured words and cold. “I am not paid in a saucer of milk or a handful of grain. My reasons are my reasons. I speak of balances, Man, but it is late for that. My aid has been commanded, and I must give it.”

“Then we will take it,” said Scaga, with an anguished motion toward the door. “Out there, today.”

“Give me time,” said Arafel. “Hold against them in your own strength, and wait.” She turned, looked on Branwyn and looked last on him, without anger, without passion at all. “Do not go out onto the walk,” she said. “Stay within. Wait.”

Her voice dimmed, and she did, so that there was only the stonework and a chair, and the silence after her.

“Arm!” Scaga shouted at the men, for still the alarm was sounding, and they had not answered it. “Come and arm!”

They ran. Ciaran stood still in the hall, feeling naked and alone. He realized the stone was in plain sight about his neck, and touched it, but it gave him nothing.

He looked back, into Branwyn’s eyes. There was terror there.

“I knew her,” Branwyn said “We were friends.”

“What happened?” he asked, disturbed to realize how meshed this place had been, forever, in the doings of Eald. “What happened, Branwyn?”

“I went into the forest,” she said. “And I was afraid.”

He nodded, knowing. There were then the two of them in the circle of fearing eyes. Lady Meredydd looked on them with a terror greater than all the rest, as if it were a nightmare she had shared. A daughter—who had walked in the forest, that they had gotten back again from Eald. Scaga knew, he too—who had seen a flinching from iron, and known clearly the name of the ill. It was terror come among them; but it had been there always, next their hearts.

“I am Ciaran,” he said slowly, to hear the words himself, “Ciaran’s second son, of Caer Donn. I lost myself in the forest, and I had her help to come here. But of the King, of your lord—I never lied. No.”

No one spoke, not the ladies, not the harper. Ciaran went to the bench by the fire and sat down there to warm himself.

“Branwyn,” Meredydd said sharply.

But Branwyn came and sat down by him, and when he gave his hand, took it, not looking at him, but knowing, perhaps, what it was to have walked the paths he took.

Arafel would come back. He trusted in this; and he remembered what Arafel had said that the others had not been willing to hear, except only Scaga, who might not have understood what she had answered.

Eald had dreamed in long silence; and Men asked that silence broken. Hehad done so, seeing only the power, and not the cost. He held tightly to Branwyn’s hand, which was flesh, and warm, and he wondered if his hand had that solidness in hers.

War was coming, not of iron and blood. They were mistaken if they expected iron and fire of Arafel; and he had been blind.

He was not, now.

SEVENTEEN

The Summoning of the Sidhe

She walked quickly, and that was swiftly indeed, through the mists which rimmed her world, into the soft green moonlight on the silver trees. The deer and other creatures stared at her and came no nearer.

And when she had come to the heart of Eald, that grassy mound starred with flowers, and the circle of aged trees, then all of Eald hushed, even to the warm breeze which sported there. Moonlight glistened and glowed in the hearts of stones which hung on the tree of memory, and on the silver swords which hung nearby, and the armor and the treasures which held the magics of Eald. The magics slept, but for what sustenance they gave. Sleeping too, were the memories of all the faded Daoine Sidhe, which were the life of Eald.

She cast off the aspect she wore for Men, stood still a moment listening for the faintest of sounds, and then for no sound at all, but the whispering of elven voices. From one to the other stone she walked, touched them gently and drew their memories into life, so that none slept, not the least or the greatest.

And in the world of Men, Ciaran shuddered, and stared at the fire before them, feeling a stirring which shivered through the very earth. All that Men stood upon seemed like gossamer, threatening to tear.

“What is wrong?” asked Branwyn. “What do you feel?”

“The world is shaken,” he said.

“I feel nothing,” she said, as if to reassure him; but it did not.

Eald stirred. Arafel stood amid the grove and looked about her and listened; and at last went among the treasures of Eald and gathered up armor ages untouched, which had been hers. She put it on, mail shining like the moon itself, and took up her bow, and shafts tipped with ice-clear stone and silver. She took up her sword, and gathered the sword of Liosliath, his bow and all his arms. She climbed the knoll, laid down her burden, and sat down with her sword across her knees. She shut her eyes to Eald as it was, and listened to the stones.

“Eachthighearn,” she whispered to the air, and the silence trembled. A breeze began, which whispered down the green grass of the knoll and set the leaves to stirring and the stones to singing.

It moved farther, coursing narrowly through the trees, across the meadows, making flowers nod, and the hares which moved by moonlight looked up and froze.

It touched the waters of Airgiod, and skimmed them with a little shiver.

It blew among the trees the other side of Airgiod, and branches stirred.

“Eachthighearn: lend me your children.”

The breeze blew along the distant flanks of hills, making them shiver, a nodding of grasses; and it traveled farther still.

Then it began to blow back again, through hills and forest, recrossing Airgiod’s quiet waters, into meadows and into the grove, stirring the grasses of the knoll, with sighings of the swaying stones and a faint tang of sea breeze, recalling mist, and partings, and the cries of gulls.

Arafel shuddered in that wind, and the grayness beckoned. A taint of melancholy came over her, but she held fast to her stone, and opened her eyes and saw the grove as it was.

“Fionnghuala!” she called. “Fionnghuala! Aodhan!”

The breeze fled back again, laden with the green glamor of Eald, with sweet grass and shade, with summer warmth. It fled away, and the air grew still.

Then a wind began to blow returning, softly at first; and with greater and greater force in its coming, rattling the branches and making Airgiod’s waters shiver, flattening the grasses and sweeping like storm into the grove, where the stones blazed with sudden light. The sky was clear, the stars pure, the moon undimmed, but storm crackled in the air, whipped the leaves, and Arafel sprang to her feet, holding the sword in her two hands. The force of lightnings stood about, shivered in her blowing hair and played about the swords in the trees. Thunder began, far away and growing in the wind, stirring like deepest song to the lighter chiming of the stones and the rush of leaves.

And with the wind came brightness in the night, one and the other, like moons coursing close to earth, with thunder in their hooves and moonlight for their manes . . . above the earth they ran, together, as they had always coursed side by side.

“ Fionnghuala!” Arafel hailed them. “Aodhan!”

The elven horses came to her in a skirling of wind, and the thunders bated as they circled her, as pale Fionnghuala stepped close and breathed in her presence with velvet nostrils shot with fire, gazed at her with eyes like the deer, wide and wonderful. Aodhan snuffed the breeze and shook his head in a scattering of light, stamped the ground and shook it.

“No,” said Arafel sadly. “He is not here. But Iask, Aodhan.”

The bright head bowed and lifted. She belted her sword at her side and took up the arms which had been Liosliath’s. Fionnghuala came to her, whickering. She seized the bright mane in one hand and swung up, and Fionnghuala stamped and turned, with Aodhan beside. The pace quickened and the wind scoured the trees, swept the grass, a flicker of lightnings crackling in the manes and in her hair.

“Caer Wiell,” Arafel said to them, and Fionnghuala ran, easily above the ground. The mist lay before them, but the wind swept into it, and lightnings lit it, making clear the shapes long lost there, the upper course of Airgiod, the shapes of faded trees. Shadows were caught by surprise and fled in terror, wailing down the wind as thunder took a steady beat and mists were scattered.

Lightning blazed in Caer Wiell’s court, danced there, with thunder-mutterings . . . stood still, and horses and rider looked on chaos, a gateway near to yielding, a scattering of men in flight from the terror which had broken in their midst. “Ciaran!” she called. “I am here!”

And Ciaran rose from his place beside the fire, no more there, no more holding the hand of Branwyn, whose voice wailed after him in grief.

He stood in the courtyard, with the stone burning like fire against his heart, with lightnings crackling about him and above him . . . and the dreams were true.

Arafel slid down, a gleam of silver armor, and held out such armor to him in both her arms. He took it and put it on, buckled on the elvish sword, and all the while his heart was chilled, for the cold went from it to the center of him, and the lightnings surrounded them. The human day was murky, clouded; but they stood in otherwhere, and elven moonlight was cast on them, pale green; night went about them, an aura of storm, and of the two horses, he knew one for his.

“Aodhan,” he named him. “Aodhan. Aodhan.” And the horse came to him, stood waiting.

“Not yet,” said Arafel, for there were others about them, human folk, who huddled against the wind, faces stark and frightened in the reflected glow, women and children and wounded men. They had no word to say to her; there were none from her to them. She walked toward the gate with Ciaran at her side and the elvish horses walked after.

“Scaga,” Ciaran said, lifting his hand toward the wall. “Scaga,” she repeated, and the old warrior looked down from the chaos on the walls, his face distraught.

“What you can do,” Scaga said, “we beg you do.”

“Beware, Scaga, what you have already asked. You have horsemen; ready them to ride with us, if they will.”

The old warrior stood still several beatings of a mortal heart. He was wise, and feared them. But he called men to him, and came down the stairs, shouted orders at boys, and commanded the horses saddled. Arafel stood still, thoughtfully took her bow from off her shoulder, and strung it. She might, she thought, go to the wall, might aid them there. But iron arrows flew in plenty, and there was time enough for that.

“Mind,” she said to Ciaran, “when you ride the shadow-ways, you are safe from iron—but you cannot strike at Men. Shift in and out of them; that is wisest”

“We can die,” he said, “—can we not?”

“No,” she said. “Not while you wear the stone. There is the fading. And there are other fates, Ciaran. Death is out there. Step into the shadow-ways and you will see him. Leave Men to me, where Men want killing. I am kinder than you know how to be. The arrows—save them: they are too dire for Men.”

“Then what shall I do?”

“Ride with me,” she said softly. “When one can do much—wisdom must guide the hand, or folly will.—Hist, they are ready.”

Boys and men brought the horses of the keep, handled, a clattering in the yard, and men ran from the defense of the walls and the gate to take them. Aodhan whickered softly and Fionnghuala saluted them too, and the mortal steeds herded together, ears pricked, nostrils straining. But Arafel walked among them, touched one and the other, named them their true names, and calmed them. “He is Whitetip,” she told a rider; “and she if Jumper. Call them true and they are yours.” The Men stared at her, but none durst question, not even Scaga, Whitetip’s rider.

She looked toward the gate, which tottered beneath the ram. Fionnghuala stepped closer to her, dipped her head and shook it impatiently.

“Do not leave me,” she bade Ciaran. “You have compelled my help. I do not compel: I ask.”

“I am by you,” he said.

“Scaga,” she said. “Bid them open the gates.” And quietly, to Ciaran: “Oftenest, Men see what they will, and cannot truly see us. Even these. Well for them they do not.”

“Do I,” he asked, “see you as you are?”

“I cannot know,” she said. “But I know you. And you had power to call my name. One must see to do that.”

He said nothing. She seized Fionnghuala’s mane and swung to her back. He mounted Aodhan, and the horse suffered it with a shiver, a flaring and quivering of the nostrils, for it was not his rider, but Ciaran knew the dream about his neck, of which Aodhan was part. Fionnghuala tossed her head, and the wind rose.

SEVENTEEN

The Summoning of the Sidhe

She walked quickly, and that was swiftly indeed, through the mists which rimmed her world, into the soft green moonlight on the silver trees. The deer and other creatures stared at her and came no nearer.

And when she had come to the heart of Eald, that grassy mound starred with flowers, and the circle of aged trees, then all of Eald hushed, even to the warm breeze which sported there. Moonlight glistened and glowed in the hearts of stones which hung on the tree of memory, and on the silver swords which hung nearby, and the armor and the treasures which held the magics of Eald. The magics slept, but for what sustenance they gave. Sleeping too, were the memories of all the faded Daoine Sidhe, which were the life of Eald.

She cast off the aspect she wore for Men, stood still a moment listening for the faintest of sounds, and then for no sound at all, but the whispering of elven voices. From one to the other stone she walked, touched them gently and drew their memories into life, so that none slept, not the least or the greatest.

And in the world of Men, Ciaran shuddered, and stared at the fire before them, feeling a stirring which shivered through the very earth. All that Men stood upon seemed like gossamer, threatening to tear.

“What is wrong?” asked Branwyn. “What do you feel?”

“The world is shaken,” he said.

“I feel nothing,” she said, as if to reassure him; but it did not.

Eald stirred. Arafel stood amid the grove and looked about her and listened; and at last went among the treasures of Eald and gathered up armor ages untouched, which had been hers. She put it on, mail shining like the moon itself, and took up her bow, and shafts tipped with ice-clear stone and silver. She took up her sword, and gathered the sword of Liosliath, his bow and all his arms. She climbed the knoll, laid down her burden, and sat down with her sword across her knees. She shut her eyes to Eald as it was, and listened to the stones.

“Eachthighearn,” she whispered to the air, and the silence trembled. A breeze began, which whispered down the green grass of the knoll and set the leaves to stirring and the stones to singing.

It moved farther, coursing narrowly through the trees, across the meadows, making flowers nod, and the hares which moved by moonlight looked up and froze.

It touched the waters of Airgiod, and skimmed them with a little shiver.

It blew among the trees the other side of Airgiod, and branches stirred.

“Eachthighearn: lend me your children.”

The breeze blew along the distant flanks of hills, making them shiver, a nodding of grasses; and it traveled farther still.

Then it began to blow back again, through hills and forest, recrossing Airgiod’s quiet waters, into meadows and into the grove, stirring the grasses of the knoll, with sighings of the swaying stones and a faint tang of sea breeze, recalling mist, and partings, and the cries of gulls.

Arafel shuddered in that wind, and the grayness beckoned. A taint of melancholy came over her, but she held fast to her stone, and opened her eyes and saw the grove as it was.

“Fionnghuala!” she called. “Fionnghuala! Aodhan!”

The breeze fled back again, laden with the green glamor of Eald, with sweet grass and shade, with summer warmth. It fled away, and the air grew still.

Then a wind began to blow returning, softly at first; and with greater and greater force in its coming, rattling the branches and making Airgiod’s waters shiver, flattening the grasses and sweeping like storm into the grove, where the stones blazed with sudden light. The sky was clear, the stars pure, the moon undimmed, but storm crackled in the air, whipped the leaves, and Arafel sprang to her feet, holding the sword in her two hands. The force of lightnings stood about, shivered in her blowing hair and played about the swords in the trees. Thunder began, far away and growing in the wind, stirring like deepest song to the lighter chiming of the stones and the rush of leaves.

And with the wind came brightness in the night, one and the other, like moons coursing close to earth, with thunder in their hooves and moonlight for their manes . . . above the earth they ran, together, as they had always coursed side by side.

“ Fionnghuala!” Arafel hailed them. “Aodhan!”

The elven horses came to her in a skirling of wind, and the thunders bated as they circled her, as pale Fionnghuala stepped close and breathed in her presence with velvet nostrils shot with fire, gazed at her with eyes like the deer, wide and wonderful. Aodhan snuffed the breeze and shook his head in a scattering of light, stamped the ground and shook it.

“No,” said Arafel sadly. “He is not here. But Iask, Aodhan.”

The bright head bowed and lifted. She belted her sword at her side and took up the arms which had been Liosliath’s. Fionnghuala came to her, whickering. She seized the bright mane in one hand and swung up, and Fionnghuala stamped and turned, with Aodhan beside. The pace quickened and the wind scoured the trees, swept the grass, a flicker of lightnings crackling in the manes and in her hair.

“Caer Wiell,” Arafel said to them, and Fionnghuala ran, easily above the ground. The mist lay before them, but the wind swept into it, and lightnings lit it, making clear the shapes long lost there, the upper course of Airgiod, the shapes of faded trees. Shadows were caught by surprise and fled in terror, wailing down the wind as thunder took a steady beat and mists were scattered.

Lightning blazed in Caer Wiell’s court, danced there, with thunder-mutterings . . . stood still, and horses and rider looked on chaos, a gateway near to yielding, a scattering of men in flight from the terror which had broken in their midst. “Ciaran!” she called. “I am here!”

And Ciaran rose from his place beside the fire, no more there, no more holding the hand of Branwyn, whose voice wailed after him in grief.

He stood in the courtyard, with the stone burning like fire against his heart, with lightnings crackling about him and above him . . . and the dreams were true.

Arafel slid down, a gleam of silver armor, and held out such armor to him in both her arms. He took it and put it on, buckled on the elvish sword, and all the while his heart was chilled, for the cold went from it to the center of him, and the lightnings surrounded them. The human day was murky, clouded; but they stood in otherwhere, and elven moonlight was cast on them, pale green; night went about them, an aura of storm, and of the two horses, he knew one for his.