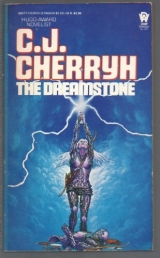

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

But come she did when her heart was healed. She expected the child where she would always be, at the forest’s edge; and when she did not find her there . . . at least, she thought, Branwyn would be playing on the hillside on so bright a midsummer day; and finally, seeking with persistence, she went even to the stones of Caer Wiell, man-hewn with painful iron.

So she found Branwyn at last, on the tower’s crest, in that sheltered nook where the wind could not reach.

The child’s shape had changed. It was a budding woman in a woman’s gown, who stared at her in alarm and did not truly remember her, forgetting childish dreams.

Branwyn had brought bread there for the birds, and stopped in the very motion of her hand, the cornflower eyes greatly amazed, not seeing howher visitor had come, but only that she was there, which was the way most mortals looked at Arafel when they saw her at all.

“Do you remember me?” Arafel asked, saddened at the change she saw.

“No,” said Branwyn, wrinkling her nose and tilting her head back to stare at her visitor, from soles of her feet to a crown of her head. “You are poor.”

“So some see me.”

“Did you beg of me on the road? You should not have come inside.”

“No,” said Arafel patiently, “Perhaps you once saw me differently.”

“At our gate?”

“Never. I gave you a flower.”

The blue eyes blinked, and did not remember.

“I offered you magic. I did you daisy chains, and found you in the woods.”

“You never did,” Branwyn breathed, cupping the crumbs in both her hands. “ I stopped believing in you.”

“So easily?” asked Arafel.

“My pony died.”

It was hate. It wounded. Arafel stood and stared.

“My father and Scaga brought me home. And I never went back.”

“You might . . . if you would.”

“I am a woman now.”

“You still remember my name.”

“Thistle.” Branwyn drew back, out of her shadow. “But little-girl playmates go away when girls are grown.”

“So I must,” said Arafel.

And she began to. But she stopped on a last forlorn hope and cast a glamor as once she had done, on the birds which hovered round about, silvering their wings. Branwyn quickly cast crumbs, and the birds alit and fought for them, so that the gleaming faded in a knot of wings and thieving. She threw more. Such were Branwyn’s magics, to tame wild things, by their desires. The cornflower eyes lifted, dark and ill-wishing, conscious of their own power and disdaining forever what was wild.

“Good-bye,” said Arafel, and yielded up the effort which held her so far out of Eald.

She faded back then, out of heart to linger there.

“Did I not warn you?” Death made bold to ask her, when next their paths crossed. Then in anger Arafel banished him from her presence, but not from the wood, for she was out of sorts with Men. The dream she had dreamed of humankind had proved more than vain, it was turned altogether against her, like the child who had grown as the saplings had grown in Death’s new forest, taking root in this world, and not in hers.

She slipped within the safer, kindlier light of her moon, and into the forest of Eald as her eyes saw it, a forest which had never faded since the beginning of the world, save those areas gone for good. Here all the leaves were silvered in the moon’s greener, younger glow; here waters sang, and the birds were free, and the deer wandered with all the stars of night in their eyes.

It was her consolation then, to dream, to walk the woods she loved, and to keep that which remained as it had always been, forgetting Men. Of midsummer nights, sometimes she came, and saw mortal Eald grown wilder and more deserted still. How Death fared, she had no knowledge, nor cared, though it seemed that he fared well, and hunted souls.

ELEVEN

Dun na h-Eoin

The banners fluttered over the tumbled stones, the watchfires flickered in the dusk, like stars across the plain. There was war. It had raged from the Caerbourne to the Brown Hills to Aescford and south again, for the King had risen, Laochailan son of Ruaidhrigh, to claim the hall of his fathers, ruined as it was.

Evald had come, of course. He was among the first, riding out of Caerdale to forestall the King’s worst enemies in the days before the King declared himself. He came with Beorc Scaga’s son, and armed men and no few stout farmers’ sons out of the dale, with all the strength that he could muster. And Dryw the son of the Dryw of Niall’s day, rode from the southern mountains with the largest rising of that folk since Aescford. So Luel rose; and Ban; they were expected. Latest came the folk of Caer Donn, high in the hills: lord Ciaran led them. Ranged against them were Damh and An Beag, the wild men of the Boglach Tiamhaidh, and the bandit lords of the Bradhaeth and Lioslinn.

And the war was long, long and bitter, and Evald felt little of glory in it: they named him in songs, but more and more he understood the Cearbhallain, for what they sang as brave he remembered most as mud and fear and being cold and hungry. But all the same he fought, and when he had time to think at all, he spent it missing Meredydd and his daughter and his fireside. He had pains in his joints and his scars when it rained. A great deal of the war seemed to be marching and riding, moving bands of men here and there and forestalling the enemy at one point to have them break out in another burning and looting of what they had lately made safe, so that they had had great pains to make a border and to hold it, for the marshes could never be trusted and the hills were full of warfare.

But at Dun na h-Eoin all that had changed, where campfires gathered and the enemy massed so many they looked like a blight upon the land, their backs against the hills.

Then was a battle, fierce and long, fought from the breaking of one day to the evening of the next, and the dark birds gathered thick as the smoke had been before. But the King prevailed.

“Your leave,” Dryw ap Dryw asked of the King that day on the field: “They’ll have no rest of me.”

“Go,” said the King. Dryw was himself pale and spattered with blood, straining at the recall like some hound called back from the hunt. “Keep them on the move.”

So Dryw leapt onto his horse and gathered his men about him, afoot, many of them, accustomed to move like shadows among the hills.

“By your leave,” said Evald, “I would go with Dryw. An Beag and Damh are old enemies of my hold—and they have force left. The most of my men are here with me; if they should come at Caer Wiell now—”

“We will come at their backs,” said the King. “At all possible speed. Let Dryw harry them as he can.”

“But Caer Wiell—” said Evald. His heart was leaden in him looking around at the desolation, the clouds of birds vying with the smokes of fires to darken the sky. It was not well to dispute with Laochailan King; he was a man of middling height, Laochailan, fair with eyes of a pale cold blue that never took fire. He had outlived his counselors. They had held him on the leash most of his life, and he was cold, seldom roused. Even in battle his killing was cold; in policy he was deliberate and immovable. And Evald turned his shoulder and strode away with a turmoil in his thoughts. It was treason in his mind, but the will of the Cearbhallain still held him, so that it was would and would not with Evald. He was on the verge of gathering his folk and riding away despite the King; Beorc Scaga’s son hurried to his side seeing stormclouds in his eyes, seeing wrack and ruin in the offing, on the bloody field.

“Cousin,” the King called after him.

Evald strode to a stop and turned, lifted his head, keeping his anger behind his eyes. “My lord King.”

“I will not be scattering my men, some here, some there. You will not be leaving this place without my will.”

“Caer Wiell was refuge for your cousin and stronghold for men that held against all your enemies. It holds now against An Beag and Caer Damh and makes their homecoming dangerous. My steward is a capable man to hold against the force they left behind, but he has too few men in his command. I have stripped my land, giving you every man, every weapon I could bring. Now the onslaught comes at Caer Wiell, and what profit to you if Caer Wiell should fall? You would lose all the valley of the Caerbourne; and it would be strong against you—as strong as it ever was for you, lord King, and as dearly bought.”

Not even this brought passion to the King’s face. “Do you think to ride against my command, cousin?”

For a moment breath and sense failed Evald. The field, the King, the counselors about him swam in a bloody haze. They were close by the ruins of Dun na h-Eoin: the black birds settled on its broken walls to rest, some too sated to take wing. They began to pitch tents, some bright with the green and gold and most leathern brown, even among the slain, amid the wailing of the wounded. Men removed the bodies, looting them too; or carried the wounded to what care they could give them; or despatched the hopeless or the fallen enemy. That was the manner of the King’s war, and the sound and the stink of it muddled the mind and made right and wrong unclear. Evald’s hand was on his sheathed sword; and blood had gotten into his glove and dried about his fingers, whether his own or others’ he had not yet explored. He thought only of his home, and his eyes saw nothing clearly.

“Will you obey,” the King asked, “or no?”

“The King knows I am loyal.”

“Then come. Come take counsel with me. Now.”

Evald considered, looked at Beorc, Scaga’s younger image, beside him. Beorc would ride; and gladly. And thereafter they would be rebels against the King, and no less to be hunted. If they were rebels, then the King might fall, for Dryw would go with them, and so the southern mountains and dale would do the thing that would ally them with An Beag and Caer Damh, in deed though never in heart. And perhaps the King saw that looming before him, since he had called him cousin twice in the same address and spoke to him courteously. Laochailan was cold, but he was clever too, outside the cold determination which had peopled this field with dead. And he knew what was necessary.

“Come,” Evald said to Beorc quietly, and so they went, across the littered field with its canebrake of spears standing in corpses, of tattered banners of the Bogach and the Bradheath of, death and agony.

They had pitched a tent for the King among the ruined stones of Dun na h-Eoin, in the courtyard, by the struggling oak which had somehow survived the fires. They had driven the pegs between the shattered paving stones and into what had been a garden. Doves had sung there. Now carrion crows flapped their dark and sluggish wings, startled by their coming. And to this state the King retreated, drawing with him others of the lords.

As they gathered, Evald glowered about him and tried to think what there was to do—for he would far rather now have been the least of men in Dryw’s company than the lord he was. There was Beorc by him and no other, for he had no kinsman but the King himself, a king who would as lief not remember that dark history or how he had come to be. Ciaran of Donn was there with his sons Donnchadh and Ciaran Cuilean, a fey and strange lot. Fearghal of Ban came with his cousins, small dark men and blood-handed, like Dalach of Caer Luel and his brothers. They were northerners all of them and some from the plains, and none of them had any close ties to the dale or the south.

So perforce Evald came into the tent with them, and bided his time while the King’s servants helped Laochailan with his armor and one brought them wine to drink. It was the color of blood. Evald took the cup and it had the taste of it as well, a coppery ugliness in the smoky air, the reek of sweat that was on them.

“Dryw has sped after them,” the King said to those who had not been there earliest. “He will keep them moving and never give them rest.”

“I say again,” Evald began, but Laochailan King turned that pale cold glance on him.

“You have said much,” said Laochailan. “You try our patience.”

“I serve my King from a hold that has been his from my father’s time.”

“From the Cearbhallain’s,” the King said softly, as if it had to be explained, and the color leapt to Evald’s face.

“And your cousin’s, lord.” Evald kept his voice steady, set down the cup and stripped the glove from his hand. Some sword or axe had cut through the leather. The blood was his. “As you kindly remember. I ask your leave—no, I beg it, to go now and keep Caerdale in your hands. They will join with their own forces. Dryw may not be enough for them when they have gained what strength they have in their own holds. They will gather forces again—”

“Do you lesson me in warfare?”

They were of an age, he and his King, born near the same year. “I know my lord King has wide concerns. So I would take this small one on myself.”

“And shall we all go riding to our own holds?” asked Fearghal, ‘Two years it has taken to bring us and the traitors to this field, and lord Evald would have us go each to his own defense again.”

This field is half empty,” Evald said. “The enemy has gone, has it passed your notice, lord of Ban? We sit here licking our wounds while theirs will be healed when they have reinforced themselves, and their strength be doubled if they should take Caer Wiell. More than doubled. In its full strength, Caer Wiell could hold for longer than we may have strength in us to hurl against it, with all the Bradheath at our backs.”

“I will not have dissent,” said the King. “That is deadlier than swords. Nor will I release any but Dryw. His men are light-armed and apt to this kind of war. You fear too much, cousin. Your steward is a skilled man in war; and Caer Wiell has defenders. If anything An Beag is apt to draw off its attackers to come in our faces, not against your lands.”

“That was not the way I learned An Beag. No. Pardon me, lord King, but they know the value of Caer Wiell in their hands, and I know An Beag, that they will take what chance they have. Dryw may try but they may hold him in the hills—and I fear some all out attack against Caer Wiell before this is done, sparing nothing. We have hurt the enemy, never killed them. A wounded beast is still to fear.”

“Is fear your counsel then? No, hear me. I will not divide my forces. I will brook no talk of it.”

“ Set us through the pass, lord King; and when you come at their backs then we will be at their faces. If we are divided, then reunite we will, over their corpses. But let Caer Wiell fall and we will leave our corpses at every step we take into the dale.”

The King’s fair face never turned color but his eyes were cold. He lifted a hand that bore the Old King’s ring and silenced the others with a gesture. “You are too forward. I will not yield in this.”

“Lord,” Evald muttered, and bowed his head and took np his cup again, moved off from the King’s presence, toward Beorc who kept to the shadow, for he did not trust his wits or his tongue just now. “Go,” he whispered to Beorc, “take horse and take at least the message of what happened here.”

“I will,” said Beorc, and bowed and was almost out the door with a turn upon his heel, a hasty man like his father.

“ Recall your man,” the King said. “Hold him!”

Spears came down athwart the doorway. “Beorc!” Evald cried at once, knowing Beorc’s mind. Beorc stopped but scantly short of harm, and lowered the hand he bad almost to his sword.

“Where in such haste?” asked the King. “Dare I guess?”

A lie tempted Evald. He rejected it and looked Laochailan in the eye. “My messengers have the habit to come and go. Should the enemy know more of what was done on this field than my own folk?”

It was perilous. The King’s eye had that chillness that went with his deepest wrath. “Cousin,” said Laochailan, “messages are mine to send. Do you not agree?”

“Then I beg you send Beorc and quickly. He knows the way.”

“I will not have it said a man of this host vent home, not the lord of Caer Wiell, not his steward’s son, not the least man of his following.”

“Lord King,” said Ciaran of Caer Donn. “But a messenger—there is treachery in An Beag and Damh. There would be no whispering in the camp at this man’s going. It would be well understood—at least by Donn. The dale is at our doorstep, and if Caer Wiell should fall it would be like the old days, with burning and looting in the hills. A messenger to give them heart and ourselves to come at the backs of our enemies—but we will be slow. We have the longer way to go. And what if their heart failed them in Caer Wiell?”

“You make yourself a part of this contention,” the King said wryly, and he frowned, for Donn had favor with him. “But Caer Wiell will have no lack of heart. After all, they defend their own lives. And that is trustworthy in these dalemen.”

“Lord,” Evald said, hot with passion, “but the choice of a defender might be a sortie if he hoped for no help—they are brave, my folk, but they may also be desperate.”

“Lord King.” It was a voice hitherto unheard in council, Ciaran Cuilean, the younger son of Donn. “You gave your word no man of us should go home before the war is done. But Caer Wiell is not my home. And I know the hills.”

There was a deep frown on his father’s face and on his brother Donnchadh’s. But the King turned to him with his anger sinking. “So. Here is one man who has the gift of courtesy. And one I would be loath to lose.”

“Never lost,” the younger Ciaran said. He laughed, tallest of all his kindred, fairer than most and more lighthearted. “I have scoured those hills often enough. I can ride through them with less trouble now, if the King will, and maybe quicker than Beorc, who knows? He has not had the hills for his hunting, and I have.”

“Then you will carry lord Evald’s message,” the King said. “Do you frame it for him, cousin, and let us be done with it. I have given you all I will.”

A fell suspicion came on Evald then—that his cousin the King had some fear of him, feared messages and secrets passed—feared this kinship with him. It was a dark thought and unworthy. Others followed it, as dark and fearful. He drove them all away. “Lord King, my lord of Donn, my gratitude.” He worked the ring from his finger. “My steward’s likeness you can know from his son. Show this to him. Speak to my lady: I send this ring to her. Tell her how things stand. That whatever they hear they must hold a little time, and the King will be coming at An Beag from the back.”

“Lord,” said the younger Ciaran, taking the ring, “I will.”

“There will be peril in it,” Evald said.

“Aye,” said Ciaran, just that, which so quietly spoken mended all his thoughts of Donn.

“Speed well,” Evald said earnestly,” and safely.”

“Your leave, sir—lord King.” So Ciaran embraced his father, but his brother would not, and excused himself to the door of the tent.

“I am in your debt,” said Evald quietly. His pride was hurt, and anger still rankled in him, for it was less than he had wanted. A terrible fear was in him that the King wished the war to go toward the dale and batter down its strength awhile, for it was too rich and too well-situated and its lord was a kinsman. But that was too dire, even thinking what the war had come to. It was too great a waste. He looked on the young man Ciaran as young and high-hearted as once he had been, and all his heart went with the man as he walked from out the tent and into the dying day. But he ached with his wounds, and there was counsel to be held. He set his hand on Beorc’s shoulder, silently wishing him to peace, and Beorc’s arm was hard and stiff with anger.

So the King took counsel of them, how they should map the last assault on An Beag and Damh and the Bradhaeth, while the cries of the wounded and of the carrion crows mingled in the evening. Evald shivered and drank his wine. He served the King as his father would, if he had lived to see the day; and for his mother’s sake; and little for his own.

“That is a good man they sent,” Beorc said quietly while the King called for wine. “They speak well of the youngest son of Donn.”

“So shall I,” Evald said, “of all Donn, ever after this.”

As for Ciaran, he delayed little in his going, seeking after the best horse he could lay hand to, taking his brother’s shield with the crescent moon of Donn upon it, for his own was broken.

“Take care,” his brother said, Donnchadh, dark as he was fair, less tall, less favored by the King or even by their father.

“I shall,” Ciaran said soberly, seeing to the gear, and took the wineflask his brother pressed on him. “That will come welcome on the trail.”

“You should have kept silent. You never should have thrust yourself into this.”

“It is no small message,” Ciaran said, “the saving of the dale.”

“He never trusts the dale. Never. It is unsavory. And never you forget it.”

“I shall not,” Ciaran said, and hung the shield on his saddle, with the parcel of bread and meat a servant brought him. He slung his sword there too, and turned and embraced his brother longer than his wont at partings. “Evald galls the King. But that is not saying he is no true man, far too true to lose . . . Keep you safe, Donnchadh.”

“And you,” his brother said, holding him by the arms. “You take it far too lightly. As you take everything.”

“And you are far too worried. Is this more than riding into the same hills with the enemy in strength in them? More to fear is Dryw: I should hate him to take me for some wild man of the Bradhaeth. Keep yourself safe. I will see you at Caer Wiell—and I shall have been dining on plates and sleeping in a fine soft bed, while you shiver in the dew, Donnchadh.”

“Do not speak of sleeping.”

“Ah, you are too full of omens. I shall fare better than you do, and worry more for you before the walls than myself behind them. Only see that you come quickly and we will push the rascals north and be done with them. Be more cheerful, Donnchadh.”

So he took his leave, and flung himself into the saddle and rode away, taking the longer path at first, which was less littered by the dead and seeming-dead. The smokes of fires lit the hills, campfires and the fires lit by the pit where they dragged the dead.

It was not an auspicious hour. He would gladly have rested. But he served the King and lived to do it when others he knew had not. And he had to take Dryw’s way through the hills and not fall into ambush, either of Dryw or An Beag.

He lost no time in going now, through the wrack of war. Truth, he was not as light about the matter as he had told Donnchadh, but he saw ruin in delaying the army at Dun na h-Eoin, ruin for more than Caer Wiell. It was twice Laochailan’s failing, to delay too long upon a field and throw away half of what they had gained; and the dale was too close to Donn. Now it was rushing all downhill, the King on the verge of moving. He was, he hoped, the first pebble before the landslide—for now Donn would give the King no peace. And so they would remember this ride of his, he thought, for he rode to herald not alone the battle for the dale, but what might well prove the telling battle of all the years of war.

TWELVE

The Faring of Ciaran Cuilean

It was not so swift a ride, from Dun na h-Eoin’s ruins through the hills. Once Ciaran met with Dryw’s folk, but only once, and that was to his liking, for the southrons were sudden men and apt to haste in their killings. He suspected their presence sometimes, a silence of birds where birds ought to sing, a strangeness in the air that he could not put name to. But at last he had passed all of that manner of thing and reckoned that he was past Dryw’s farthest easterly advance—for Dryw would go off to the north direct to the Caerbourne as the enemy had fled, while his own course cut deeper into the woods.

But at last he reached the river himself, and forded it, choosing rather the hazards of the far shore than the ill repute of the southern one. He had been in the saddle so long he had forgotten when he had rested—his resting when he took it was only for the horse, and then he was back in the saddle again, sleeping little, aching with the weight of the mail and of his bruises from the battle. Now he kept the shield uncased on his arm, trusting none of this dark wooded way through the vale of the Caerbourne. He was in the dale now. There were no friends hereabouts. He watched about him, no longer hoping that Dryw was close. This was the darkest, the most dangerous portion of his ride. He had managed it so that he reckoned to pass An Beag in the dark, and hoped that he knew well enough where he was.

The day waned, and at times the horse faltered on the narrow trail, which ran over stone and through woods, along the black waters of the Caerbourne, which rushed and splashed over rock in its shallow places, frothing white in the gathering murk. The brush was too thick here for his liking though it offered him cover. He was a horseman; he preferred something less tangled than this thicket, which wore at the horse and in places made every step a risk, in which their moving sounded all too loud. Least of all did he like the whispering that filled the twilight here, rustlings not of the horse’s making, little movings which seemed wind alone, and might be something else. All this forest was a place of ill legend; and they did not love such legends in his hills, in Caer Donn, where the old powers were still dreaded, where ruined towers and strange stones poked from out the gorse and broom and reminded them of all things older than the gods, old as stone and like the stone, everywhere underfoot. There were places in his own hills he would not ride by twilight, not for any cause; and names not for speaking by dark or brightest day. The terror was as close here. The horse, long-ridden and drenched in sweat as it was, still threw its head and rolled its eyes and stared into this shadow and the other, nostrils wide. Where it could it kept a steady pace through the forest shadow, a panting rhythm of leather and metal and the beat of hooves.

Then two pale moths came flying, a whipping arrow-sound . . . Ciaran flung up the shield; and a blow jarred it, while the horse reared up and leaned leftward in a sudden loosening of life.

He sprawled clear of the dying horse, shield lifting, jarred by a second shaft thumping into the wood while others hissed through brush and his back hit the thicket. He scrambled desperately to cover himself and to run, tore his ungloved right hand on thorns, while the crash of brush warned him of enemies coming. His back met a tree and he braced himself there on his feet. He had his sword from sheath, and they came on him in a mass in the forest dark, with staves and knives. Blows battered at his shield, and he hewed at them with every stroke that his weary left arm could gain him room to take—the blade bit and there were screams. They tried to come at him from behind, and he swung with his shoulders still to the tree and killed one of them and another, rammed his shield under a bearded chin and hewed again, with ebbing strength, for there was a quick numbing pain in his side and he knew something had gotten through, in the joinings. An axe swung down on him, shivered the top of the shield and stuck fast. He let the shield go and swung the sword two-handed, clove ribs and wrenched the blade free in back-swing, while a staff came down on him. The blow dazed him; but he rammed the blade’s point into that one’s belly and slew him too . . . while brush crashed and cries were raised beyond– Help, ho! help, we have him!

He took to the brush and began to run, staggered across the thigh-deep rush of the Caerbourne, chilled and sodden, waded ashore and set out running on the other bank, sought brush again when arrows hissed after. Voices cursed in the gathering dark. He sought higher ground with a wildling’s instinct, not to be driven into some hole against the stream’s winding banks. Branches tore at him and snapped. His limbs turned leaden with the weight of armor, and his side ached. A veil seemed fallen over his eyes and the little light in heaven was dimmed, all murky, yet for a time he ran with hope, for it seemed that his pursuers had fallen behind. He climbed, took ways closer and closer with brush and twisted, aged trees, through tangles so dense that even bracken would not grow, past stony upthrusts and over jagged ground. He hoped; and then the brush about him crackled to a chuckling, and the wind stirred through the branches like a rising storm. He ran farther, until all the sound in his ears was his heartbeat, and the brush breaking and his own harsh breath tearing his throat

But another breathing grew at his heels, the whuff of a running horse, the beat of hooves which broke no brush as it came.

He spun about to face attack, but there was nothing there but the blackness, and the wind and a cold which settled about his heart. Then he feared as he had never feared in battle, and ran as if effort before this were nothing. The ache in his side was more than want of breath; he pressed his swordhand’s wrist there and felt the ebb of blood.

He was weakening. He heard a chuckling and now knew the name of that rider which followed him, and the name of the wood into which he had strayed. And when he was nigh to falling he set his back against an aged tree in a space clearer than the others, where it seemed that he might at least have the grace of seeing his enemy come on him.

Shadow came, and a spatter of rain, a rattle of thunder, and the baying of hounds. Shadows flooded among the trees, black bits of night which rushed and leaped for him. His sword swept through them, nothing hindering, and a coldness fastened and worried at his arm, numbing all the way to his heart.

He cried aloud and tore free, ran, leaving a fragment of himself in the jaws, and the sword was no longer in his hand. The shadows coursed behind him, and the hoofbeats rang like the pulse in his ears and the hoarse breathing was like his own. The enemy was not behind him, but lodged in his side, where the wound worked at his life. A part of his soul was theirs, and they would tear him to nothing when they came on him again, a rending far worse than the first. Rain spattered into his face and blinded him, dampened the leaves so that they clung to him and his armor was soaked so that he did not know now what was blood and what was rain. He stumbled yet again, in a crash of thunder, and of a sudden as surely as there was a horror behind him he conceived of safety in the trees ahead, where seemed a mound overgrown, a swelling of the land with life, where the trees grew vast, and strong, stretching out their limbs in sympathy.