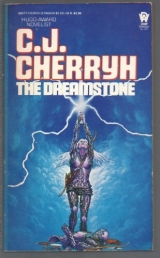

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

“A king’s own harper.”

Fionn never looked at her and never ceased to play. “Ah, worse things he has done. But that was seven years ago. And so I came, when I was grown—wandering the roads and harping in all the halls. Last of all to Caer Wiell. Last of all to him. All this winter I gave Evald songs he liked. But at winter’s end I came down to the hall at night and mended the old harp. So I fled over the walls. From the hill I gave it voice and a song he remembered. For that he hunts me. And beyond that there is no more to tell.”

Then softly Fionn sang, of humankind and wolves, and that song was bitter. Arafel shuddered to hear it, and quickly bade him cease, for mind to mind with her in troubled dreams Evald heard and tossed, and waked starting in sweat.

“Sing more kindly now,” she said. “More kindly. It was never made for hate, this harp, this gift of my folk to the Kings of Men. There were such gifts once long and long ago, did you not know? It sounds through all the realms of Eald, mine and thine and places far darker. Never sing dark songs. Harp me brighter things. Sing me sun and moon and laughing, sing me the lightest song you know.”

“I know children’s songs,” he said doubtfully. “Or walking songs. The great songs—well, it seems an age for dark ones.”

“Then sing the little ones,” she said, “the small ones that make Men laugh—oh, I have need to laugh, harper, that most of all.”

Fionn did so, while the moon climbed above the trees, and Arafel recalled elder-day songs which the world had not heard in long years, sang them sweetly. Fionn listened and caught up the words in his strings, until the tears ran down his face for joy.

There could be no harm in Ealdwood in that hour: the spirits of latter earth which skulked and strove and haunted Men fled elsewhere, finding nothing in this place that they knew; and the old shadows slipped away trembling, for they remembered.

But now and again the elvish song faltered, for there came a touch of ill and smallness into Arafel’s own mind, a cold piercing as the iron, bringing thoughts of hate, which she had never held so close.

Then she laughed, breaking the spell, and put it from her. She bent herself to teach the harper songs which she herself had almost forgotten, conscious the while that elsewhere, down in Caerbourne vale, on the hill of Caer Wiell, a Man’s body tossed in sweaty dreams which seemed constantly to mock him, with sounds of eldritch harping that stirred echoes and sleeping ghosts.

With the dawn, she and Fionn rose and walked a time, and shared food, and drank at a cold, clear spring she knew, until the sun’s hot eye fell upon them and cast its numbing spell on all the Ealdwood.

Then Fionn slept in innocence, while Arafel fought the sleep which came to her. Dreams were in that sleep, her time to dream while heshould wake, Evald, the lord in the valley, and those dreams would not stay at bay, not as her eyes grew heavy and the midmorning air thickened with urging sleep. They pressed at her more and more strongly. The Man’s strong legs bestrode a great brute horse, and his hands plied the whip and his feet the spurs, hurting it cruelly. She dreamed the noise of hounds and bunt, a coursing of woods and hedges and the bright spurt of blood on dappled hide—Evald sought blood to wipe out blood, because the harping still rang in his mind, and he remembered . . . harper, and hall, and the harper who sang the truth of how he served his king. He hunted deer and thought other things. She shuddered at the killing her own hands did, and at the fear that gathered thickly about the valley lord, reflected in his comrades’ eyes, reflected in his wife’s and son’s pale faces when he came riding home again with deer’s blood on his clothes.

It was better that night, when the waking was Arafel’s and her harper’s, and sweet songs banished fear and dreams. But even then Arafel recalled and grieved, and at times the cold came so heavily on her that her hand would steal to her throat where the moongreen stone had hung. Her eyes brimmed once suddenly with tears. Fionn saw that, and tried to sing her merry songs instead.

They failed, and the music died.

“Teach me another song,” he begged of her, attempting distraction. “No harper ever had such songs. And will younot play for me?”

“I have no art,” she said, for the last true harper of her own folk had gone long ago to the sea. The answer was not all truth. Once she had played. But there was no more music in her hands, none since the last of her folk had gone and she had willed to stay, loving this woods too well in spite of Men. “Play,” she asked of Fionn, and tried desperately to smile, though the iron closed about her heart and the valley lord raged at the nightmare, waking in sweat, ghost-ridden.

It was that human song which Fionn had played in his despair on the hillside, bright and defiant that it was: Eald rang with it; and that night the lord Evald did not sleep again, but sat shivering and wrapped in furs before his hearth, his hand clenched in hate on the stone which he possessed and would not, though it killed him, let go.

But Arafel quietly began to sing, a song of elder earth unheard since the world had dimmed. The harper took up the tune, which sang of earth and shores and water, the last great journey, at Men’s coming and the changing of the world. Fionn wept while he played, and Arafel smiled sadly and at last fell silent, for it was the last of all elvish songs. Her heart had gone gray and cold.

The sun returned at last, but Arafel had no will now to eat or rest, only to sit grieving, because she had lost her peace. She would have been glad now to have fled the shadow-shifting way back into otherwhere, to her own fair moon and softer sunlight. She might have persuaded the harper to come with her now. She thought now perhaps he could find the way. But now there was a portion of her heart in pawn, and she could not even take herself away from this world: she was too heavily bound to thoughts of it. She fell to mourning and despair, and often pressed her hand where the stone should rest. It was time, the shadows whispered, that Eald should end. She held in ancient stubbornness. And she felt some feyness on her, that many things together had gone amiss, that even on her the harp had power.

He hunted again, did Evald of Caer Wiell, now that the sun was up. Sleepless, driven mad by dreams, he whipped his folk out of the hold as he did his hounds, out to the margin of the Ealdwood, to harry the creatures of the woods’ edge—having guessed well the source of his luck and the harping in his dreams. He brought fire and axes across the Caerbourne’s dark flood, meaning to fell the old trees one by one until all was dead and bare.

The wood muttered now with whisperings and angers. A wall of cloud rolled down from the north on Ealdwood and all deep Caerdale, dimming the sun. A wind sighed in the faces of the Men, so that no torch was set to wood for fear of fire turning back on the hold itself; but axes rang, all the same, that day and the next. The clouds gathered thicker and the winds blew colder, making the Ealdwood dim again and dank. Arafel still managed to smile by night, hearing the harper’s songs. But every stroke of the axes by day made her shudder, and while Fionn slept by snatches, the iron about her heart grew constantly closer. The wound in the Ealdwood grew day by day, and the valley lord was coming: she knew it well.

And at last there remained no rest at all, by day or night.

She sat then with her head bowed beneath the clouded moon, and Fionn was powerless to cheer her. He sat and regarded her with deep despair, and reached and touched her hand for comfort.

She said no word to that offering, but rose and invited the harper to walk with her awhile. He did so. And vile things stirred and muttered in the shadow of the thickets and the briers, whispering malice to the winds, so that often Fionn started aside and stared and kept close beside her.

Her strength was fading, first that she could not keep these voices away, and then that she could not keep herself from listening. Ruin,they whispered. All useless.And at last she sank on Fionn’s arm, eased to the cold ground and leaned her head against the bark of a gnarled and dying tree.

“What ails?” he asked, and patted her face and pried at her clenched and empty fingers, opened the fist which hovered near her throat, as if seeking there the answer. “What ails you?”

She shrugged and smiled and shuddered, because even now by the glare of fires and torches in the dark, the axes had begun again, and she felt the iron like a wound, a great cry going through the wood as it had gone ceaselessly for days; but he was deaf to it, being what he was.

“Make a song for me,” she said.

“I have no heart for it.”

“Nor have I,” she said. A sweat stood on her face, and he wiped at it with his gentle hand and tried to ease her pain.

And again he caught and unclenched the hand which rested, empty, at her throat. “The stone,” he said. “Is it thatyou miss?”

She shrugged, and turned her head, for the axes then seemed loud and near. He looked that way too—and glanced back deaf and puzzled, to gaze into her eyes.

“ ’Tis time,” she said. “You have to be on your way this morning, as soon as there’s sun enough. The New Forest will hide you after all.”

“And leave you? Is that what you mean?”

She smiled, touched his anxious face. “I’ve paid enough.”

“How paid? What did you pay? Whatwas it you gave away?”

“Dreams,” she said. “Only that. And all of that” Her hands shook terribly, and a blackness came on her heart too miserable to bear: it was hate, and aimed at him and at herself and all that lived; and it was harder and harder to fend away. “Evil has it. He would do you hurt, and I would dream that too. Harper, it’s time to go.”

“Why would you give such a thing?” Great tears started from his eyes. “Was it worth such a cost, my harping?”

“Why, well worth it,” she said, and managed such a laugh as she had left to laugh, that shattered all the evil for a moment and left her clean. “I have remembered how to sing.”

He snatched up the harp and ran, breaking branches and tearing flesh in his headlong haste, but not, she realized in horror, not the way he ought—but back again, to Caerdale.

She cried out her dismay and seized at branches to pull herself to her feet; she could in no wise follow. Her limbs which had been quick to run beneath this moon or the other were leaden, and her breath came hard. Brambles caught and held with all but mindful malice, and dark things which had never had power in her presence whispered loudly now, of murder.

And elsewhere the wolf-lord with his men drove at the forest with great ringing blows, the poison of iron. The heavy human body which she sometime wore seemed hers again, and the moonstone was prisoned near a heart that beat with hate.

She tried the more to make haste, and could not. She looked helplessly through Evald’s narrow eyes and saw—saw the young harper break through the thickets near them. Weapons lifted, bows and axes. Hounds bayed and lunged at leashes in the firelight

Fionn came, nothing hesitating, bringing the harp, and himself. “A trade,” she heard him say. “The stone for the harp.”

There was such hate in Evald’s heart, and such fear, it was hard to breathe. She felt a pain to the depth of her as Evald’s coarse fingers pawed at the stone. She felt his fear, felt his loathing of the stone. Nothing would he truly let go. But this—this, he abhorred, and was fierce in his joy to lose it.

“Come,” the lord Evald said, and held the stone dangling and spinning before him, so that for that moment the hate was far and cold.

Another hand took it then, and very gentle it was, and very full of love. She felt the sudden draught of strength and desperation—she sprang up then, to run, to save—

But pain stabbed through her heart, with one last ringing of the harp, with such an ebbing out of love and grief that she cried aloud, and stumbled, blind, dead in that part of her.

She did not cease to run; and she ran now that shadow-way, for the heaviness was gone. Across meadows, under that other light she sped, and gathered up all that she had left behind, burst out again in the blink of an eye and elsewhere.

Horses shied in the dark dawning and dogs barked; for now she did not care to be what suited men’s eyes. Bright as the moon she broke among them, and in her hand was a sharp silver sword, to meet with iron.

Harp and harper lay together, sword-riven. She saw the underlings start away from her and cared nothing for them; but Evald she sought, lifted that fragile silver blade. Evald cursed at her, drove spurs into his horse and rode down at her, sword swinging, shivering the winds with a horrid sweep of iron. The horse screamed and shied; he cursed and reined the beast, and drove it for her again. But this time the blow was hers, a scratch that made him shriek with rage.

She fled at once. He pursued. It was his nature that he must. She might have fled elsewhere and deceived him, but she would not. She darted and dodged ahead of the great horse, and it broke down the brush and the thorns and panted after, hard-ridden.

Shadows gathered, stirring and urgent on this side and on that, who gibbered and rejoiced for the way the chase was tending, to the woods’ blackest heart—for some of them had been Men; and some had known the wolf’s justice, and had come by that to what they were. They reached, these shadows, but durst not touch him: she would not have it so. Over all the trees bowed and groaned in the winds and the leaves went flying as clouds took back the dawn in storm: thunder in the heavens and thunder of hooves below, cracks of brush scattering the shadows.

Suddenly in the dark of a hollow she whirled, flung back her dimming cloak and the light gleamed suddenly: the horse shied up and fell, casting Evald sprawling among the wet leaves. The shaken beast scrambled up and evaded its master’s reaching hands and his threats, thundered away on the moist earth, breaking branches as it went, splashing across some hidden stream in the dark, and then the shadows chuckled. Arafel stood still, fully in his world, moonbright and silver. Evald cursed, shifted that great black sword of his in his hand, which bore a scratch now that must trouble him. He shrieked with hate and slashed.

She laughed and stepped into otherwhere as iron passed where she had stood, shifted back again and fled yet farther, letting him pursue until he stumbled with exhaustion and sobbed and fell in the storm-dark, forgetting now his anger, for the whispers came loud, in the moving of the trees.

“Up,” she bade him, mocking, and stepped again to here.Thunder rolled above them on the wind, and the sound of horses and hounds came at distance.

Evald heard the sounds. A joyous malice came into his eyes at the thought of allies; his face grinned in the lightnings as he gathered his sword.

She laughed too, elvish-cruel, as the horses neared them—and Evald’s confident mirth died as the sound came over them, shattering the heavens, shaking the earth—a Hunt of a different kind, from a third and other Eald.

Evald cursed and swung the blade, ranged and slashed again, and she flinched from the almost-kiss of iron. Again he whirled his great sword, pressing close. She stepped elsewhere, avoiding the iron, stepped back again with her silver blade set full in his heart and suddenly here.The lightning cracked—he shrieked a curse, and, silver-spitted—died.

She did not weep or laugh now; she had known this Man too well for either. She looked up instead to the clouds, gray wrack scudding before the storm, where other hunters coursed the winds and wild cries wailed across belated dawn—heard hounds baying after something fugitive and wild. She lifted then her fragile sword, salute to lord Death, who had governance over Men, a Huntsman too; and many the old comrades the wolf would find following in histrain.

Then the sorrow came on her, and she walked the otherwhere path to the beginning and end of her course, where harp and harper lay, deserted, the Wolf’s comrades all fled. There was no mending here. The light was gone from his eyes and the wood of the harp was shattered.

But in his fingers lay another thing, which gleamed like the summer moon in his hand.

Clean it was from his keeping, and loved. She gathered the moonstone to her. The silver chain went again about her neck and the stone rested where it ought. She bent last of all and kissed him to his long sleep, fading then to otherwhere.

And the storm grew.

SIX

Setting Forth

The storm had come over the Steading, a wall of cloud and wind which whipped the branches of the oak and ripped the young spring leaves.

And in it Caoimhin came home, running breathless, panting and stumbling as he came along the fence row, fighting the wind which drove across his path.

So he came to the gate and up the path, and young Eadwulf who had come out to see to the sheep saw him first: “Caoimhin!” Eadwulf cried.

But Caoimhin passed on, running and holding his side. Blood was on his face. Eadwulf saw that and clambered over the pen and ran after him.

So Niall saw him, not knowing him at first, seeing only that a man had come to the Steading: he left his securing of the barn against the storm and came running from the other side as many did from many points of the Steading, from the house and from the pens, leaving their work in haste.

But when he had come into Caoimhin’s way his heart turned in him, seeing the quiver and the bow, the gauntness of the man, the recent scar that crossed his unshaven face, the blood that ran on it from scratches.

“Caoimhin!” Niall said and caught him up arm to arm. “Caoimhin!”

Caoimhin fell, collapsing to his knees, and Niall went down to his own, holding his arms while Caoimhin’s body heaved with his breathing. The bloody face lifted again, glazed with sweat, pale and gaunt. His beard and hair showed dirt and grass from his falling. “Lord,” Caoimhin said, “he’s dead, Evald is lost and dead.”

A moment Niall stared at him blankly and Caoimhin’s hands gripped his arms as the others gathered round. “Dead,” Niall said, but nothing else he understood. “But you are back, Caoimhin—You found the way.”

“ Dead,hear me, Cearbhallain.” Caoimhin found strength to shake at him. “Caer Wiell is without a lord—it is your hour, your hour, Cearbhallain. He went into the wood and never out again; he has crossed the fair folk and never will he come out again. Fionn—”

“Is he with you?”

“The harper’s dead. Evald killed him.”

“Coinneach’s son.”

“ Listen to me.There is no time but now. There are men would ride with you, I have told you—”

“The harper dead.”

“Cearbhallain, are you deaf to me?” The tears poured down Caoimhin’s face. “ I came back for you.”

Niall knelt still in the dust. Beorc was there, and set his large hands on Caoimhin’s shoulders. Most of the Steading gathered and was still gathering, some standing, some kneeling near, and the latest come were shushed so the silence thickened, a deep and terrible waiting.

“Tell me,” Niall said, “when and where. Tell me from the beginning.”

“From time to time—” Caoimhin caught his breath, leaning his hands now on his knees. “We met, Coinneach’s son and I. Fionn Fionnbharr. On the road, when I went after him. And so we parted. Only he brought word to me now and again—how he fared, and where. He wintered in Caer Wiell as he had said he would and the men—I have gathered old friends, my lord, men you knew. I have never been idle, about the roads and the hills and the fringes of the river; I have been to Donn and Ban and all such places and back again, and sent men to Caer Luel—”

“—in my name?”

“What less would bring them? Aye, your name. But we have kept quiet, lord, and hunted and done little—in your name. And we took our news from the harper when he could bring it, even from Caer Wiell. But lately he fled the hold—fled with Evald behind him, and so they report him dead, murdered—but Evald himself died after, this very morning. A man of ours was hidden near his camp; and brings word his men believe him dead—fear other things less lucky to talk of—in this storm—” Caoimhin fought for breath and caught his arms. “They will be riding back to Caer Wiell this morning, today, lordless, and leaderless—Caer Wiell is yours again. You cannot deny it now. Men are ready to follow you—Fearghal and Cadawg and Dryw, Ogan, the lot of them—”

“You had no right!” Niall flung Caoimhin’s hands aside and rose, swung his arm to clear himself a space and stopped at the shocked and staring faces of those about him, of Lonn and the others, and turned back to look on Beorc himself, his eyes stinging in the wind which howled and whipped about them. Lastly he looked down at Caoimhin, who looked up at him, hurt and worn as the world had worn him, bearing such scars as he had been spared in the Steading, where no war could come—and all at once his peace was shattered beyond recall. It was not a clap of thunder, although thunder rolled; it was only a sudden clear sight, how men fared that he once had loved, how life and death had gone on for all the world without him. He felt robbed, for in the stormlight everything about him seemed dimmed and less beautiful than it had been. There was gray about the Steading, which had never been. There were flaws in the faces about him he had never seen. Tears started from his eyes and ran crooked in the wind. “So, well, we ought to be on our way,” he said, and helped Caoimhin to his feet. It was hard to look at the others, but he must, at Beorc’s solemn face, whose red mane whipped in the gale; at Aelfraeda, whose golden braids were immovable in strongest winds; at Siolta and Lonn, steadfast; at Scaga whose thin young face had hollowed almost to manhood in the passing years. “I have a thing to see to,” Niall said to them. “Like for the wolf and foxes—there comes a time, doesn’t there? The deer are gone. They’ll hunt one another in the hills.”

“You’ll want food,” said Aelfraeda.

“If you will,” Niall whispered and looked at Beorc. “If you will—Banain—”

“She will bear you,” said Beorc, “I do not doubt. And if she will, then what she wills.”

“I need my sword,” Niall said then, and turned away, not having the heart for facing Beorc or Aelfraeda any longer. He flung his arm about Caoimhin. “Come up to the house. There’ll be ale and bread at least”

So they went. He found Scaga at his left, trudging along with him and Caoimhin, and so he set his left hand on Scaga’s shoulder, but the boy bowed his head and said nothing to him, nothing at all, while the thunder rumbled over the Steading and the wind blew the young leaves of the oak in shreds.

They came into the house, into warmth and a busy flurrying after drink and bread and the wherewithal to feed two and more hungry men on their way. Niall went to the corner by the fire and took his sword, but he did not draw it, not even to see to the blade of it. The sheath and hilt were covered with dust. Perhaps rust had gotten to it as it lay by the hearth. But it was not a thing for bringing to light in Beorc’s house and in Aelfraeda’s. Diarmaid brought the remnant of the armor he had had, and this he put on with Scaga and Lonn and Diarmaid to help him, while Caoimhin sat shaking with weariness and cramming food into his mouth. He had no cloak any longer. He put on the warm vest he had had on before, hung the dusty sword on his shoulder and went out into the chill of the storm to find Banain in the barn.

“I’ll come with you,” Scaga cried after him, following him outside.

“No,” he shouted back to the porch. “Stay warm. Help Aelfraeda. I’ll not be leaving without seeing you. Stay inside.”

The thunder cracked. He turned and ran, past the gate of the yard and down the hill to the barn and so inside, where was shelter from the wind and the warm smell of straw and horses.

“Banain,” he whispered, coming to her in the shadow of the stall. He brought the bridle she had been wearing when she came to them. They had mended its broken rein for the children’s riding; but he had never put it on her. He hugged her about the neck and got a nudging in the ribs in return, a whickering from the pony near her in the dark. “Banain,” he said. “Banain.”

“Cruel,” a small voice piped.

He whirled about with his back to the mare. The Gruagach sat on the pony’s back, peering at him across the rails of the next stall.

“Cruel to take Banain. Cruel Caoimhin, to take his lord away. O where is peace, Man? Never, never, for Caoimhin; now never for Banain; never for Cearbhallain. O never go.”

“I would I never had to.” He recovered himself and turned about again, stroking Banain’s neck. His hands were still cold from the wind outside. He coaxed the bit into Banain’s mouth and drew the strap past her ears. She turned her head and butted him gently in the chest, snorted as a dark shape landed on the rail in front of them.

“Never go,” said the Gruagach.

“I have no choice.”

“Always, always comes a choice. O Man, the Gruagach warns you.” It shifted and hugged itself upon its rail. “Wicked Caoimhin, wicked.”

Niall took the cheekstrap and backed Banain out of her warm nest of straw and comfort. The Gruagach followed, a scurrying in the straw: it came out into the light of the half-open door well-dusted, with straws in its hair, and hugged itself and rocked. “Never go,” it said.

A sadness came on Niall. He would never have expected such a feeling toward the Gruagach, but he knew that where he fared would be nothing like the creature, never in all the cold strange world. Already it seemed small and wizened and more afraid than frightening. He held out his hand as he would have to a child. “Gruagach,” he said, “take care of the people I love. And this place. I have stayed too long.”

The Gruagach touched his hand with fingertips, so, so lightly, and cocked his head and looked up at him, then shivered and bounded away to the top of the apple-bin, burying his head in his arms. “She sees, she sees,” he wept, “o the terrible face, the terrible lights of her eyes, she sees!”

“Who?” asked Niall. “What—sees?”

“She is waked,” the Gruagach cried, looking from between his arms. “She is waked, waked, waked! and the harp of Kings is broken. O the terrible sword, the sharp, the wicked sword! O never go, Man, O Man, the Gruagach warns you, never go.”

“Who is she?”

“In the forest, deep and still. The harp came there because it had to come. Things of Eald must. Beware, o beware of Donn.”

The thunder rumbled and muttered over them. Banain threw her head. “I have no choice,” Niall said shivering. “I never had. Farewell.”

He flung open the door and led Banain out. He would have shut it for the pony’s sake, but the Gruagach was in the doorway. He swung up to Banain’s back and rode up toward the house, from which the others were coming down.

So he should not have the chance to come into the house again. He felt cheated—of even that little time. The world seemed the colder as the wind howled and whipped at him and Banain, who danced and fretted under him for distaste of this weather and for the thunder—and never yet it rained. Something keened. It was not the wind. He looked up and behind him and saw the Gruagach perched on the rooftop of the barn, a lumpish knot of hair.

“Man,” it wailed. “O Man.”

The others came about him, Caoimhin and Beorc and Aelfraeda and all the house so far as he could judge. “Here,” said Niall, flinging a leg over Banaia’s back. “Caoimhin, you must ride. You’re spent.”

Caoimhin would not, not without arguing about it; but Niall slid down and put him up, and on his own shoulders he took the healthy pack Aelfraeda had put up for them. He kissed her cheek and pressed Beorc’s hand. He looked round on all the faces, and they seemed already far from him, slipping away from him, a love he did not know how to hold onto any longer.

“Scaga,” he said, missing one. “Where is Scaga?”

Everyone looked around, but the boy was not to be found. “He was with me,” said Siolta, “only a moment ago.”

“He is hurt,” said Lonn.

So Niall shook his head heavily, well understanding that. “Come,” he said to Caoimhin, and hitched the cords of the pack on his shoulder. “Good-bye,” he said. “Good-bye.”

“Farewell,” said Beorc, “and wisely. A blessing beyond that I cannot give you, though I would.”

Niall turned his shoulder then and walked beside Caoimhin on Banain. The wind battered at them, and never a drop of rain fell from the black clouds above. The grass and the tender crops flattened in waves, and now and again the lightning flashed in the clouds. He looked back more than once and waved each time, but now they all seemed hazy, shadowed under the storm that had come over the Steading. His heart felt heavier and heavier and his steps were leaden.

“Have care,” a small voice wailed from the hilltop at his right “Have care.” It was the Gruagach, sitting on a stone in a sea of blowing grass. “O Man, it is no common rain this brings.”

“That fell creature,” Caoimhin muttered.

“Speak it fair,” said Niall. “O Caoimhin, speak it only fair.”

But it was gone, the rock deserted. Banain tossed her head and snorted in the wind.

“Here, lord, she can carry two,” Caoimhin said. “Ride with me.”

“No,” said Niall. A last time he looked back, but a hill was passing between him and those behind: he waved a last time, but they perhaps did not see. He felt a loneliness and desolation, blinked as some wind-borne dust hit his eyes and rubbed at them as he walked along, blind for the moment. When he had gotten them clear he looked back again, squinting in the gusts.

The fences at least should have been in sight. There was only the blowing grass. “Caoimhin,” he said, “the fences are gone.”

Caoimhin looked, but never said a word. Again Niall rubbed his eyes, feeling a great cold settle into his bones, as if the wind had finally gotten through. Caoimhin had found his way back again, the thought came to him; Caoimhin had come as the harper had come, never reckoning how hard it was—for need, for need of him.A haste had come on him, all the same, a blind numb haste to go back to the world again: Ogan, Caoimhin had named the names—Ogan and Dryw and the others, names that he had known, bloody names of bloody years, of hisyears with the King—