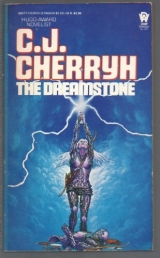

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

THE DREAMSTONE

by C.J. Cherryh

Book One of Ealdwood

BOOK ONE

The Gruagach

ONE

Of Fish and Fire

Things there are in the world which have never loved Men, which have been in the world far longer than humankind, so that once when Men were newer on the earth and the woods were greater, there had been places a Man might walk where he might feel the age of the world on his shoulders. Forests grew in which the stillness was so great he could hear stirrings of a life no part of his own. There were brooks from which the magic had not gone, mountains which sang with voices, and sometimes a wind touched the back of his neck and lifted the hairs with the shiver of a presence at which a Man must never turn and stare.

But the noise of Men grew more and more insistent Their trespasses became more bold. Death had come with them, and the knowledge of good and evil, and this was a power they had, both to be virtuous and to be blind.

Axes rang. Men built houses, and holds, rooted up stone, felled trees, made fields where forests had stood from the foundation of the world; and they brought bleating flocks to guard with dogs that had forgotten they were wolves. Men changed whatever they set hand to. They wrought their magic on beasts, to make them dull and patient. They brought fire and the reek of smoke to the dales. They brought lines and order to the curve of the hills. Most of all they brought the chill of iron, to sweep away the ancient shadows.

But they took the brightness too. It was inevitable, because that brightness was measured against that dark. Men piled stone on stone and made warm homes, and tamed some humbler, quieter things, but the darkest burrowed deep and the brightest went away, heartbroken.

Save one, whose patience or whose pride was more than all the rest.

So one place, one untouched place in all the world remained, a rather smallish forest near the sea and near humankind, keeping a time different than elsewhere.

Somewhen this forest had ceased to be a lovely place. Thorns choked it, beyond its fringe of bracken. Dead trees lay unhewn by any woodman, for none would venture there. It was a perilous place by day. By night it felt far worse, and a man did well not to build a fire too neat the aged trees. Things whispered here, and the trees muttered with the wind and perhaps with other things. Men knew the place was old, old as the world, and they never made peace with it.

But on a certain night a man was weary, and he had seen very much of horror and of the world’s hard places, so that a little fire to cook by seemed a very small hazard against others he had run this day, the matter of a few twigs to cook a bit to eat.

He had come and gone a great deal on the banks of the river Caerbourne and in the fringes of this forest, for five whole years. If there were outlaws hereabouts he knew them all by name. And if there were other dangers he had never met them, so they failed to frighten him, this night, and on other nights when he had come this far beneath the aged boughs and heard the rustlings and the whisperings of the leaves. He made his little fire and cooked his fish and ate it, which seemed to him like a feast after his famine of recent days. He felt home again; he felt safe; he looked forward to a bed among the leaves where no two-legged enemy would be likely to come on him.

But Arafel had noticed him.

She had little interest in the doings of Men in general. Her time and her living were very much different from the years of humankind, but she had seen this Man before as he slipped about the margins of her wood. He was deft about it and did no harm, and he was wary and hard for harm to come to: such a Man never quite disturbed her peace.

But this night he took a fish from the Caerbourne’s stream and built a fire to cook it, beneath an ancient oak. And this was far too great a familiarity.

So she came. She stood watching for a while unnoticed in her gray hooded cloak, in the shadows among the oaks. The Man had had his fish, leaving only the naked bones in the fire, and now knelt, cherishing the warmth of the tiny flame and heap of ash, cupping his hands close above it. He was rough-looking, with a weathered countenance and gray-streaked hair—a lean and weary Man with the taint of iron about his person, for a sword lay close beside his knee. She had been apt to anger when she came, but he sat so small and quiet for so tall a Man, clinging to so small a warmth in the great dark of the wood, that she wondered at him, how he had come, or why, presuming so much for so little comfort. She was not the first to come. The shadows moved beyond his little fire and hissed in indignation. He never seemed to notice, deaf to them and blinded by the light he clung to.

“You should take more care,” she said.

He snatched at his great sword and came to one knee all in one motion.

“No,” she said quietly, moving forward. “No, I am quite alone coming here. I saw your fire.”

The sword stayed half-drawn across his knee. He had heard nothing, seen nothing until now. A gray-mantled figure showed like a trick of moonlight in the thicket, so dim even the tiny fire might have blinded his eyes, but he had no excuse at all for his ears. “Who are you?” he asked. “Of An Beag, would you be?”

“No. Of this place. I rarely stir out of it. Put the sword away.”

He was off his balance and not accustomed to that. Why he was sitting still at all instead of standing sword in hand was not quite clear to him, only that there had never seemed a moment of clear decision since the stranger started speaking. The voice was smooth and fair. He could not get the timbre of it in his mind, whether it was young or old or what it was even when it was just dying in the air, no more than he could make out the figure in the dark, but he found he had slid the sword back into its sheath, not having clearly decided to put it back at all. His hands were cold. “Share if you like,” he said, with a motion toward the fire. “The warmth, at least. If it’s food you want, catch your own. I’ve eaten all I had.”

“I have no need.” The stranger came nearer, so silently no leaf whispered, and settled at the side of the tiny clearing on the dead log that fended the wind from his fire. “What would your name be?”

“Give me yours,” he said.

“I have many.”

Little by little the chill of the ground had come creeping up to him, and now the fire between them seemed all too dun and small. “And what would one of them be?” he asked, because he was always a man to want answers even when they were ill.

“I have marked your coming and going hereabouts.” The answer came so still and soft the rustle of a leaf might have overcome it. “Other things have seen you, do you not know? Your step was always soft and quick until tonight; but now you settle in to stay—is that your hope? No, I think not. I do think not. You are wiser than that.”

She saw the hardness of his face as he stared at her. It was a face which might well have been fair once, but years and scars had marred it; and sun and wind had weathered it, so that it was fit for the rest of him, with ragged hair and ragged clothes and dark, hopeless eyes. As for him, there was no knowing what he saw of her: Men saw what they pleased to see, often as not. Perhaps to him she was some outlaw like himself or some great mail-clad warrior from over the river. His hand never let go the sword.

“Why do you come?” she asked him last

“For shelter.”

“What, in mywood?”

“Then I will leave your wood, as quickly as I may.”

“There is harm outside this circle—No, it would not be well to look just now. As for the fish and the fire, both are costly. And what will you offer me for them?”

He gave no answer. If there was any wealth he had besides the sword itself she could not tell it. And that he did not offer.

“What,” she said, “nothing?”

“What will you have?” he asked.

“Truth. For the fish and the fire tell me truly what you do in my woods.”

“I live.”

“No more than that? It seems to be a hard living. There’s a sorrow about you, Man. Is there ever joy?”

This was baiting. The Man felt it, and felt his weariness hovering over him like urging sleep. There was peril in that sleep, and that he also knew. He set the cap of his sheathed sword on the ground and leaned heavily on it, looking at the stranger, trying to look more closely, but his sight seemed to dim whenever he looked hardest, and some fold of the cloak was always casting a shifting shadow just where he looked, so that he could see nothing that was beneath it. He knew beyond a doubt that he had met one of the fair folk, and he knew it though the moment was moonbeams and shadows and something his eyes refused to see. He had never expected such a meeting in his life, being occupied with his own business, but he knew it when it was on him and understood his danger, that the fair folk were fell and deadly with trespassers, and given to dark mischief. But perhaps it was part of the binding on him that he felt no reticence at all with this stranger, as if it were the last night of the world and the last friend had come to listen. “I have come here,” he said, “sometimes. It seemed safe. I brought no enemy here. An Beag would never follow.”

“Why do they hunt you?”

“I am a King’s man.”

“And they have some quarrel with this King?”

The voice seemed innocent, fair as a child’s. The years went reeling back and back for him and he leaned the more heavily on the hilt of his sword, aching in all his bones, and laughed. “Quarrel, aye. They killed the King at Aescford, burned Dun na h-Eoin—now there is no king at all. Five years gone—” He grew hoarse in telling it. It was incredible to him that all the world was not shaken by that fall, but the figure before him stayed unmoved.

“Wars of Men. They are nothing to me. The fish matters. That touches my boundaries.”

A chill wandered up his back, but dimly through his remembered grief. “So, but I gave you the truth for it.”

“That was the price I named. Now I give you good advice: do not come again.” The shadow rose, graying into dark. “This once I will guide you to the river, but only once.”

He leaned on the sword and levered himself to his feet as if it were the last strength he had; and perhaps it was. His shoulders were bowed. His head was down for the moment, but then it lifted, and he pointed another way with a straightening of his shoulders. “Give me leave to go along the shore. A mile or so down the river I can slip my enemies and I will go as quickly as I can.”

“No. You must go as you came, and now.”

“So,” he said, and bent and patiently covered up his fire, then took up his sword, half drawing it although in his eyes was no hope at all. “But my enemies are waiting there, and whatever you are, I will make a beginning here if I have no choice. I ask you again—let me pass along the shore. I was always a good neighbor to this wood. I never set axe to it. I beg your courtesy this once. It is so small a thing.”

She considered him, so soft-spoken, so set upon his way. Almost she went fading back again and leaving this Man to the dark and the night. But there was no dark anger in him, only the sadness of something brave that once had been. So the old stag died, among the wolves; or the eagle fell; or the wolf himself went down. She thought a moment and thinking on such a heart remembered a place, a small place, the only warmth she knew among humankind.

“I shall tell you a way to go,” she said gently, “and help you come to it if perhaps you can, a place deep in the hills and not so perilous as my lands. But you must come with me now step for step and never stray: Death has been very near to you tonight. He is very skillful at stalking, more than any Man. No, never look. Come now, come, put away the sword and follow. Follow me.”

A second time he slid the sword back into its sheath and never felt the doing of it; he walked as once he had walked after bloody Aescford, out of the hills, aware first of fending branches from his face and then that he had come some distance never remembering any of it; and that he was lost. He was well-schooled in woodcraft and no man could have eluded him so close at hand, but the gray cloak melted through the thickets before him as if the branches had no substance, and though he went as quickly as he could, he could never come near his guide. He was panting, and his heart labored with a beating he could hear, so loud it dimmed all other sounds. Branches raked his face and arms. Leaves whipped past with a soft and clinging touch.

But at last the stranger waited for him on the river bank, standing against a very aged tree, so that the gray cloak might have been part of the bark in the moonlight. They had come to the widest part of the Caerbourne, where it flowed most shallowly: he knew it, every stone along the shore.

And his guide pointed him the way across.

“This is the ford,” he objected. “And they will be watching it.”

“They are not. Not this while. Perhaps not again for several nights—trust me that I know. Yonder you see the hills, and atop the first hill is a cairn; and beneath the second as you follow the river course from the narrows below the cairn, there go up the dale and up the farther hill. The place I send you, you will never see it, except you come up the dell and over against the shoulder of the Raven’s Hill . . . do they call it that, these days?”

“That is still the name.” He looked toward the shadowy line of hills beyond the river, beyond the trees. The river water danced with a light that broke beside him. He turned his head in alarm toward his companion. There was no one there, as if there had never been, only the fading memory of a voice of a high, fair tone, as he had never heard it, and the recollection of a light he had almost seen.

The world seemed dark then, and cold, and the shadows full of menace.

“Are you there?” he asked the dark, but nothing answered.

He shivered then, and slinging his sword at his back, waded the Caerbourne’s chill flood up to his waist, constantly expecting arrows from out of the dark trees on the other side, ambush and after all, the chill laughter of the fair folk at his back. There was no luck in faery-gifts. He doubted all his safety now, forever.

But nothing started on that shore except a small splash that swam away into the reeds, and he climbed out again on the side of the river his enemies held, finding no one watching, and no harm near him. He began at once to run to keep the warmth in his legs, dodging along among the few young trees which grew on the naked borders of An Beag and its villages.

He was Niall, lately called Dubhlachan and formerly other names, who had been a lord in years gone by; but the King he served now was a helpless babe hidden somewhere in the hills—so loyal hearts believed. And the loyal men lived and harried the traitors’ fields in Caerbourne vale and elsewhere as they could, which was all they could do till the young King should live to be a man.

Five years Niall had lived in the forest edges, under stone and hidden in thickets, and men had followed him, but most were dead and the rest now scattered.

So he ran, ran at last because the sun was coming, and ran because a dream in the dark wood had promised safety. He was not young any longer. He had lost all his faith in kings to come. It was only a fireside he wanted, and bread to eat, and no more hunt at his heels.

The sun came up on him and still he ran by turns, coming up into the Brown Hills. Men called them haunted, like the wood. But he had long had the habit of such places, where no comfortable men would go. The rumor only gave him hope, more and more as he came among the hills. Weariness left him, so that he ran more lightly than he had run before, through the rough stones and the desolation. The sun was on him. The sweat ran. He heard his steps fall and jar the stones together, but nothing more in all the world, as if some veil lay on his senses and the world had stopped being what it was. If the forest had been dark, this was bright, and the sun danced here, and the stones shone in the light.

He reached the Raven’s Hill and climbed. A strangeness glistened under the nooning sun, under the shoulder of the opposing hill. And so he ran, ran, ran, with a great expectation in his heart, and if he began to die in that running, still he drove himself with the hope of something, some barrier to cross, some place one only got to by chance or luck or the last hope in all the world.

It was a homely place, of fields and fences, stone and golden thatch and a crooked chimney, and the smell of bread baking, and the sun shining on the barley round about and on the dust.

“Come see, come see!” he heard someone call as he fell to his knees and full length on the ground. “O come! here’s a man come fallen in the yard!”

TWO

Beorc’s Steading

The sweat ran in rivulets on Niall’s back, and it was a good feeling, swinging a mallet and not a sword, driving the pegs in just so, to mend the grain-bin before the new harvest came in, the fields standing golden white in the sun.

A dour-faced boy brought him water: he dipped up enough to drink and poured the rest over his head, blinking in the stream, and the boy Scaga took the dipper back and sulked off about his rounds, but that was ever Scaga’s manner and no one minded. Birds lighted on the fencepost when the boy had gone, cocked wise eyes at Niall, darted down to peck a bit of grain from the dust as he turned back to work again. Dinner was foremost in his mind, one of Aelfraeda’s fine hearty dinners set beneath the evening sky as they ate in summertime, beneath the spreading oak that shaded the Steading; some would sing and some would listen, and so the stars would light them to bed until the sun waked them out of it.

That was the way of the days at Beorc’s Steading, and Beorc himself ordered matters in all this wide farm so that no days were idle and everything was done in its season, like the mending before the harvest. There were full two score hands to work, men and women and children. The fields were wide, and the orchards likewise, and the sheep grazed the hill by the spring while the cattle and the pony pastured down by the tiny brook it made. There gnarled willows shaded time-rounded stones and a child could wade most of it. Closer, where the brook came nearest the barn, lived a herd of fat pigs and a flock of geese as fat as the pigs and noisier, who bullied their way about the farm. But also about the hillside there was a wolf, a well-fed and lazy cub who liked ear-scratching; and a fawn who strayed in and nosed her way everywhere. A badger had his hole in the hollow next the turnip field; and a host of birds lived round about, from the heron who lived on the brook to the family of owls who lived in the barn. They were all lostlings. They had all come like the cub and the fawn and fallen under the peace Aelfraeda maintained. There was such a spell on them they never preyed on each other, except the heron fished the brook and the owls had the barn mice who minded no laws at all.

This extended to the two-footed kind—for they all had come, excepting Beorc and Aelfraeda themselves, as lostlings themselves, both old and young, and none were kin at all. There was old grandfather Sgeulaiche, as wizened and withered as last winter’s apple, whose hands and clever blade turned out the most marvelous things of wood, who sat on the porch in a pool of sweet smelling curls of wood and told stories to whatever girl or boy who was set to work the churn or card the wool—for there were children here, half a dozen of them, no one’s and everyone’s, like the fawn. There was of course half-grown Scaga, who pilfered food at every chance and hid it, though Aelfraeda would have given him both hands full of anything he asked—he fears being hungry, Aelfraeda said; so, let him hide all he will, and eat all he can—someday he will smile. There was Haesel hardly six and Holen more than twelve; and Siobrach and Eadwulf and Cinhil in between. Of adults there was Siolta, who was lame and in middle years, who baked and made wonderful cheeses, and there was Lonn who had a great swordcut running from brow to chin and many others beside, but his hands were sure and good with the cattle: Siolta and Lonn were man and wife, though never they had known each other before this place. There was Conmhaighe and Carraig and Cinnfhail and Flann; and Diomasach, Diarmaid and the other Diarmaid; and Ruadh; and Fitheach and the other men and women, so that there were never workers lacking for the hardest tasks inside the house or out, besides Beorc and Aelfraeda themselves, who were wherever work wanted doing, cheerful and foremost in any task.

In all, the weather blessed the place and the grain grew tall and the green apples grew round and fine; and the brook never failed in summer. There was a haze of light about the hills by daylight, so that it made the eyes sting to try to look into the distance of the Brown Hills; and the mountain shoulder lay between the Steading and the river away to the south, and between it and the harrying of An Beag and other names which seemed a dream here.

“Do you not set a guard?” Niall had asked of Beorc early, while they had tended him in the house and fed him until he was less gaunt than before. “Do you not have men to watch the way to this place? I would do that. Weapons are what I know.”

But, “No,” Beorc had said, and his face, broad and plain and ruddy, had creased with laughter. “No. You had luck to come here. Few are lucky, and them I welcome. So there is a great deal of luck on this valley of mine. If you will stay, stay: if you will go, I will show you a way to go, but if you turned round again after, I do not think your luck would find the place a second time.”

Then Niall said nothing more of boundaries and borders, perceiving some force in Beorc that kept its own limits and expected everything about him to do likewise. He is, Niall had thought then with a queer kind of shiver, more like a king than not. And king did not fit Beorc either, with his wispy nimbus of gray-red hair, his cheeks wind-burned above a beard as wild and lawless as his mane. Like a fire he was, a gust of wind, a great broad man who laughed much and kept his own counsels; and Aelfraeda was like him and unlike, a woman of strong hands and ample girth and beautiful golden braids coiled crownlike about her head, who carried her own milkpails, thank you, and wove and spun and fed strays both two and four-footed, having the law in her house and for scepter a wooden spoon.

It was a place that luck smiled on, and in which more than a usual share of amazing things happened: for weeds that happened into the crops turned up in the morning wilted and limp beside the rows so that hardly ever did one have to take a hoe to the vegetables; and if some few vegetables vanished in the same night, no one spoke of it. Tools one would have sworn were lost turned up found in the morning on the porch, fit to set a shiver up a less complacent spine. Likewise the pannikin of milk and the buttered cakes Aelfraeda faithfully set out each night on the bench on the porch turned up missing, each and every crumb, which might have been the wolf cub’s doing or the fawn’s, or the geese, but Niall never spied the cakes vanishing and had no wish to go out of nights to see.

And most peculiar, there was the Brown Man, or so Niall called him, skulking here and there in the orchards, or among the rocks, fit to account for a great deal that was odd hereabouts. “He is very old,” said Beorc when Niall reported it. “Never trouble him.”

Old he might be, Niall suspected, old as stone and hills and all, for there was something uncanny about him and bespelled. Nothing could move so quickly, coming into the tail of the eye and out again, and skipping away among the rocks. There he sat now, a small brown lump by the barn, barefoot, knees tucked up in arms, and watching, watching the mending of the bin. He was wrinkled as an old man and agile as any child; and his brown hair fell down about his hairy arms and his beard sprayed about his bare and well-thatched chest. His oversized hands and feet were furred just the same. Brown as a nut and no taller than a half-grown boy, with hair well-shot with gray and usually flecked with wisps of straw, he hung about the barn and nipped apples from the barrel and sometimes sat on the pony’s back in the stall, feeding him with good apples too.

And this Brown Man had a way about him of being there one moment and elsewhere in the next, so that when Niall cast him a second look round the corner of the shed he was gone.

On that same instant something prickled his bare back and he spun about with an oath and almost a sweep of the hammer. As quickly as he spun a shadow dived in the corner of his eye and he kept spinning, following it as it nabbed a fistful of grain from the bin: but it was gone, quick as he could turn, and round the corner of the shed. “Hey!” he cried, and hurled himself round the corner, but it was gone a second time, a wisp of brown headed around the corner.

Once he had followed it: he knew better now. It had led him over fences and stones and over the brook and back again. Now he dived back again around the corner and caught it coming round behind him. He flung the mallet, not to hit it, but to scare it.

It screamed and tucked down instead of running. It kept tucked down, its face in its hairy hands, and peered out quickly to see if another mallet was coming.

“Here now,” Niall said. “Here.” He was suddenly in the wrong and hoping no one had seen.

It ventured another eye above its hands, then spat and scampered off on its short legs.

“Perish it,” Niall muttered to himself, and then wished he had not said that either. Nothing went well this day. He left his pegs and his mallet and followed it to the barn and inside.

Straw showered down his neck. “Plague on you,” he cried, but it went scampering through the rafters disturbing the owls in a flapping of wings. “Come back!”

But it was gone and out the door.

“Do not try.”

It was Beorc who had come in behind him, and shame flooded Niall’s face. He was not accustomed to be made sport of or to be caught in the wrong either. “I would not have hit him.”

“No, but you hurt his pride.”

A moment Niall was silent. “What will mend it?”

“Be kind,” said Beorc. “Only be kind.”

“Call him back,” said Niall in sudden despair.

“That I cannot. He is the Gruagach and no one has the calling of him: he will never tell his name.”

Niall shivered then, for his luck seemed to have left him. It will end now, he thought, for frightening one of the fair folk: he remembered how he had come to the Steading, and how it needed luck to find the place and needed luck to stay.

That night he had no appetite, and set his dinner on the porch beside the platter Aelfraeda set out; but in the morning Aelfraeda’s gift was taken and his was left

Yet there was no certain turning in his luck, except that now and again he had straw dumped on his head when he went into the barn and now and again his tools vanished when his back was turned, to appear on their pegs in the barn when he came hunting others.

All this he bore with patience unlike himself, even setting an especially fine apple out where the theft was returned—which gift vanished: but so, daily, did his tools. All the same he taught himself to smile about it, concealing his misfortune and making little of it, no matter how long the walk.

So great a patience did he achieve that it even extended to the boy Scaga’s thefts, so that one day that he came on the boy pilfering his lunch in the field he only stood there, and Scaga looked up with his eyes all round with startlement

Niall had a mallet in his hand this day too, but he kept it in his hand. “Will you not leave a morsel?” he asked. “I’ve been hard at my work.”

The boy looked at him, down on his haunches as he was and ill-set for running. And he set the basket down.

“Will you have half?” Niall asked the boy. “I’d like the company.”

“There’s not much,” the red-baked rascal said, looking doubtfully under the napkin.

“There’s always enough to give half of,” Niall said, and did.

It was a silent lunch. Scaga stole from others after, but never from him. And sometimes his tools came back on Scaga’s quick legs before he missed them.

One day about that time the Gruagach came and sat and watched him, and he spied it looking round the corner of the barn at him.

“Here,” he said, his heart lifting at this approach. He offered a handful from the bin, “here’s grain. I’ve a bit of bread about me if you like. Good cheese.” The head vanished before the words had left his mouth. But it lurked about and looked at him and stole his tools only now and again, just to remind him.

His luck lasted, and the days rolled on, from summer heat to harvest: the fawn grew gangling and the wolf cub yelped at the moon of nights; and the sickles turned up sharpened on their own each harvest morning.

But one nooning a man came stumbling up the valley from the south, off the shoulder of Raven’s Hill, startling the geese.

Niall came as all the house came running. The man had fallen trying to cross the fence, a bony huddle of limbs and weapons, for he carried a bow and an empty quiver, a sword at his side. Lonn had caught him up and held him, and so Niall came, and stopped and fell to his knees in dismay, because he knew this man. “His name is Caoimhin,” Niall said. A fear had come on him as if all his safety wavered. For the briefest moment he looked beyond the fences, where the folding hills trapped his sight, half-expecting to see pursuit coming hard on Caoimhin’s heels. But then he felt a hand close on his and looked down in shame.

“Lord,” Caoimhin said, and his hand trembled in its grip on his, Caoimhin, best of bowmen they had had. “O my lord, we heard that you were dead.”

“No,” said Niall, “hush, be still, lean on me: I’ll help you walk”

Caoimhin let him lift him up, trusting only him, clinging most to him and leaning on him, so with Beorc and Lonn and Flann and Carraig and all the troop they brought him into the yard, and so into the house and Aelfraeda’s care, than which there was none better.