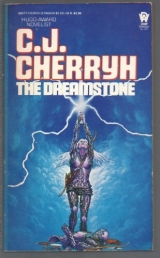

Текст книги "The Dreamstone "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Эпическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

It was broth that day and bread and butter, but Caoimhin limped as far as the porch in the evening, and then to the yard where the table groaned with food beneath the oak, and the harvesters came singing home. Having gotten that far he only stared with that far lost look of a man too hard for tears, but Niall came to rescue him and Beorc clapped him heartily on the shoulder and called for a cup of ale for him, and another plate at table.

“Here,” Niall bade Caoimhin quickly, and gave up his own seat until everyone rearranged themselves and Siolta brought a dish and cup for him. “He is Caoimhin,” Beorc said, lifting his cup to him. So they all did, and fell to one of Aelfraeda’s grand good meals.

Caoimhin tried, a bit of this and that, but his hands shook and at last he sat there with the tears running down his face and a bit of bread in his hand. But Niall put his arm about him and held him in his place, he was so weak, and if the company grew quiet a moment, they understood and the merriment picked up again. “What is this place?” Caoimhin asked when he had had a sip of ale.

“Refuge,” said Niall. “And safety. A place where ill has never been. And never shall.”

“Are we dead then?”

“No,” Niall laughed. “Never dead.”

But a niggling fear was on him. He even wished Caoimhin had never come, because this man reminded him what he had been, and brought the stink of death about him. More, he was afraid for the peace of all this place, as if it had taken some great danger to its heart.

Caoimhin lay about the house the next few days, or rested on the porch in the sunlight and the breeze, and slept much and drank and ate wholesome food when he waked, so that his face looked less haggard and less desperate.

In those first days he wanted at least his sword by him and kept it by him even napping in the sun. And ever and again his hand would stray to find it in his sleep, and his fingers curl about the sheath or hilt, so his face would lose its moment’s trouble and he would rest again. But on the third day he let it go; and the fourth he walked out of the house and left it behind, beside the hearth with his bow and his empty quiver. So he sat with old Sgeulaiche on the porch and finally strolled about the yard and out to the threshing.

There Niall saw him and wiped the sweat and the dust from his brow and came over to him.

“What,” Niall said lightly, “does Aelfraeda know you’ve strayed?”

“By your leave—”

Niall’s brows drew down. “No. Not mine. Not here.”

“My lord—”

“No lord, I say. No longer—Caoimhin.” He clapped him gently on the shoulder. “Come aside with me.”

Caoimhin walked with him, as far as the barn and into the shadow inside, and there Niall stopped. “There is no lord in the Steading,” Niall said at once, “if not Beorc himself; no lady if not Aelfraeda. And that is well enough with me. Forget my name.”

“I have rested. I am well enough to go back again—I will bring you word again. There are men of ours in the hills—”

“No. No. If you leave this place I do not think you will find it again.”

The eagerness died in Caoimhin’s lean face. From toe to crown Caoimhin looked at him and seemed to doubt what he saw as if it were his first clear look. “You have got calluses on your hands and not from the sword, my lord. There is straw in your hair. You do a farmer’s work.”

“I do it well. And I have more joy of it than anything I did. And I will tell you there is more good in it than ever I have hoped to do. Caoimhin, Caoimhin, you will see. You will see what this place is.”

“It has cast a spell on you, that much I see. The King—”

“The King.” A shudder came over Niall and he turned away. “My King is dead; the other—who knows? Who knows if he even exists? I saw my King dead. The other I never saw. A babe smuggled away at night—and who knows whose babe? Some serving maid’s? Some beggar’s child? Or any child at all.”

“I have seen him!”

“So you have seen him. And what proof is that? Any child, I say.”

“A boy—a fair blond boy. Laochailan son of Ruaidhrigh, like him as a boy could be. He has five years now. Taithleach keeps him safe—would you doubt hisword?—always on the move through the hills, so that the traitors will never find him, and they need you now—They need you, Niall Cearbhallain.”

“A boy.” Niall sat down on the gram bin and looked up at Caoimhin with the taste of ashes in his mouth, “And what am I, Caoimhin? I was forty and two when I began to serve this hope of a King to come; and my joints ache, Caoimhin, with five years’ sleeping under tree and stone. And if this boy ever comes to take Dun na h-Eoin—look at me. Twenty years it will need to make a boy a man; and how many more to make that man a king? Am I likely to see it done?”

“So, well—and who of the men dead on Aescford field will ever see him king? Or shall I? Or shall I? I do not know. But I do what I can as we always did. Where is your heart, Cearbhallain?”

“Broken. Long ago. I will hear no more of it. No more.You’ll go or you’ll stay as you wish, when you can. But stay for now. Rest. Only a little time. And see what things are here. O Caoimhin—leave me my peace.”

A long time Caoimhin was silent, looking desolate and lost.

“Peace,” Niall repeated. “Our war is done. There is the harvest; the apples are ripening; there’ll be the long wintertime. And no need of swords and no help at all we can be. It’s all for younger men. If there’s to be a king, he will be theirs, not ours. If we have begun, others will finish. And is that not the way of things?”

“Lord,” Caoimhin whispered softly; and then a sudden alarm came into his eyes at a quiet scurrying, a shadow by the door. Caoimhin sprang and hit the door and hurled the listener in the dust. “Here are spies,” Caoimhin cried, and nabbed the brown man by the hair and hauled him back struggling and gasping as he was and slammed the door.

“Let it go,” Niall said at once, “let it go.”

Caoimhin had a look at it and flung his right hand back with an oath and an outcry, for it bit him and scratched and clawed, but he held it with the left. “This is no man, this—”

“Gruagach is his name,” Niall said, and took Caoimhin’s hand from the brown man. The creature hugged Niall’s arm and danced behind him and fled, peering out again from the refuge of a pile of hay, with straw and dust clinging all over its hair.

“Wicked, wicked,” it said, a voice as slight as itself, that lifted the hairs on a man’s neck.

“He will never hurt you,” Niall promised it. Never had he heard it speak, though others said it could. “Open the door, Caoimhin—open it! Let it go!”

Carefully Caoimhin pushed at the door and light flooded in. The Gruagach stirred himself and sidled that way, closer than ever Niall had seen him clearly, face seamed and brown and bearded, eyes lightless as deep water peering out from under matted hair. It looked up at him and bobbed as if it bowed on its thick legs. And then it fled, scuttling out as quick as the breeze, and was gone.

Then Niall looked toward Caoimhin, and saw the dread there, and all the surmise. “There is no harm in it.”

“Is there none?” Caoimhin leaned against the door. “Now I know where the cakes go at night, and what the luck is in this place. Come away, Cearbhallain, come now.”

“I will never go. No. You do not know—the way of this place. Come, a bargain with me—only a little time. You would always take my word. Stay. You can always leave—but you will never find the way back again. Was it ill luck brought you here? Tell me that. Or tell me whether you would be breathing the air this morning or eating a good breakfast and looking forward to dinner. There’s no dishonor in being alive. It’s not our war any longer. It was our luck that brought us here; it was—perhaps something won. I think so. Think on it, Caoimhin. And stay.”

A long time Caoimhin reflected on it, and at last looked at the ground and at last looked at him. “There’s autumn ahead,” Caoimhin said, weakening.

“And winter. There is winter, Caoimhin.”

“Till the spring,” Caoimhin said. “In the spring I’ll go.”

The apples went into the bins; the sausages went to smoke; the oak tree shed his leaves and deep snow drifted down. The Gruagach sat on the roof by the chimney and left prints by the step where the cakes and mulled ale disappeared; and of nights he kept the pony and the oxen company.

“Tell us tales,” young Scaga said, as all the household sat about the fire. Marvelous to say, Scaga had taken to making the pony’s mash this winter without being asked; and never a thing had been missed about the house since summer. He had, from being last and least, become a thoughtful if sober lad, and attached himself to Niall’s side and by adoption, to Caoimhin’s as well.

So Caoimhin told of a winter on the Daur and a storm that had cracked old trees; and Sgeulaiche recalled being lost in such a storm. And after, when the whole house curled up to sleep each in their warm nooks, and Beorc and Aelfraeda in their great close-bed in the loft: “It is a young man’s winter,” Caoimhin said to Niall whose pallet was near his.

“A young man’s war,” said Niall.

“They have taken your lands,” Caoimhin said, “and mine.”

A long time Niall was silent. “I have no heir. Nor ever shall, most likely.”

“As for that—” Now the silence was on Caoimhin’s side, a very long time. “As for that, well, that is for young men too. Like the winter. Like the war.”

And after that Caoimhin said nothing. But in the morning a lightness was on him, as if some weight had passed.

He will stay, Niall thought, taking in his breath. At least one man of all that followed me. And then he put that prideful thought away, along with my lordand Cearbhallainand bundled himself into warm clothes, for there was winter’s work to do, the beasts to care for. The children fought snowball battles: Caoimhin joined in, stalking with Scaga round the barn. Niall saw the stealth, the skill that Caoimhin taught the boy. A moment the chill got through: but they were only snowballs, and the squeals and shouts were only children’s laughter.

The Gruagach perched on the roof, and let fall a double armful and laughed and ran.

“Ha,” it cried, going over the rooftree. “Ha! Wicked!”

“Wither it!” cried Caoimhin, but the ambush was sprung and the battle lost in pelting snowballs.

A moment Niall watched, and turned away, hearing still the squeals and hearing something else. He turned and looked back to prove to his ears and eyes what it was he heard, and succeeded, and went his way.

THREE

The Harper

The harvest had come again. The scythes went back and forth and left stubble in their wake. By morning the sheaves appeared all in rows, neatly tied; so the Gruagach slept a mighty sleep by day, and ate and ate. A pair of fawns had come this year, a fledgling falcon, a bittern, a trio of fox kits and a starved and arrow-shot piebald mare: such were the fugitives the Steading gathered. Now the falcon was flown, and the bittern too; the fox kits instead of tumbling about the porch were beginning to stray toward the margins of the Steading, going the way of the wolf; and the mare had become fast friends with the Steading’s own pony, grown fat and sleek on sweet grass and grain. The children were delighted with her and hung garlands about her neck which she contrived to slip and eat often as not: she ate and ate, and began to frisk about at daybreak as if it were the morning of the world and no war had ever been.

So here is another fled from the madness, Niall thought to himself, and loved the mare for her courage in living. He rode at times bareback and reinless when he had leisure, letting her go where she would through the pastures and the hills. He loved the feeling of riding again, and the mare swished her tail and cantered at times for the joy of it, going where she pleased, from rich pasture to cool brook to hillsides in the sunlight, or home again to stable and grain. Banain, he called her, his fair darling. She would bear him of her own will; or any of the children, or the Gruagach who whispered to her in a way that horses understood. Sometimes she was willing to be bridled and Caoimhin rode when the mood came on him, and others did, but rarely and not so well and not so far, for, as Caoimhin said, she has one love and none of us can win her.

So this year had been even kinder than the first to him. But the year was not done with arrivals.

This last one came singing, blithe as brazen, down the dusty margin of the fields, along the track the cattle took to pasture, a youth, a vagabond with a sack on his back and a staff in his hand and no weapon but a dagger. His hair was blond to whiteness, and blew about his shoulders to the time of his walking and the whim of the breeze.

Hey,he sang, the winds do blow,

And ho, the leaves are dying,

And season doth to season go

The summer swiftly flying.

Niall was one that saw this apparition. He was mending fences, and Beorc was near him, with Caoimhin and Lonn and Scaga. “Look,” said Caoimhin, and look they did, and looked at Beorc. Beorc stopped his work and with hands on hips watched the lad coming so merrily down the far hillside, Beorc seeming less perplexed than solemn.

“Here’s one come walking where he knows not,” Niall said. In a furtive smallness of his heart it disturbed him that anyone could come less desperate than himself, than Caoimhin wounded, than half-starved Banain or the grounded falcon. It upset all his world that this place could be gained so casually, by simple accident. And then he thought again on the meanness of that; and a third time that it was less than likely.

“It be one of the fair folk,” said Lonn uneasily.

“No,” said Beorc. “That he is not. He has a harp on his shoulder, and his singing is uncommon fine but he is none of the fair folk.”

“Do you know him then?” Niall asked, wishing some surety in this meeting.

“No,” Beorc said. “Not I.” There was no man living had sharper eyes or ears than Beorc. He spoke while the boy was well off in the distance and the voice was still unclear. But the song came clearer as they listened, bright and fair, and the boy came walking up to them in no great hurry: there was indeed a harp on his shoulder. It rang as he walked and as he stopped.

“Is there welcome here?” the boy asked.

“Always,” said Beorc. “For all that find the way. Have you walked far?”

For a moment there seemed a confusion in the boy’s eyes. He half turned as if seeking the way that he had come. “I came on the path. It seemed a short way through the hills.”

“Well,” said Beorc. “Well, shorter and longer than some. The hills are not safe these days.”

“There were riders,” said the harper vaguely, pointing at the hills. “But they went off their way and I went mine, and I sing as I walk so they will not mistake me—there is still some respect for a harper, is there not, in the lands about Caer Donn?”

“Ah, if you were seeking Caer Donn you are somewhat off your path.”

Now the boy looked afraid—not greatly so, but uneasy all the same. “I had come from Donn. Is this then An Beag’s land? I had not thought it reached within the hills.”

“Freeheld, this is,” said Beorc and laughed, waving an arm at all the steading, the house set on the side of the great hill, the golden-stubbled fields, the orchards, the whole wide valley. “And Aelfraeda, my wife, will give a harper a cup of ale and a place by the fire for the asking. If you’ve a taste for cakes and honey, that we always have. Scaga, show the lad the way.”

“Sir,” said the harper, quite courteous in his recovery, and made a bow as respectful as for a lord. He shouldered the strap of his harpcase and went off up the hill with Scaga’s leading, not without a troubled glance or two the way he had come, but after a few paces his step was light again and quick.

“You have misgivings,” Niall said to Beorc at the harper’s back, when he was out of hearing. “You never wondered at me or at Caoimhin. Who is he? Or what?”

Beorc continued to stare after the boy a moment, leaning on the rail, and his face had no laughter in it, none. “Something strayed. Caer Donn, he says. Yet his heart is hidden.”

“Does he lie?” asked Caoimhin.

“No,” said Beorc. “Do you think a harper could?”

“A harper is a man,” said Caoimhin. “And men have been known to lie upon a time.”

Beorc turned on Caoimhin one of his searching looks, his beard like so much fire in the wind and his hair blowing likewise. “The world has gotten to be an ill place if that is so. But this one does not. I do not fear that.”

“And what when he goes singing songs of us in An Beag?” asked Caoimhin.

“They may search as they will,” said Beorc, and shrugged and took up the rail again, “But we shall have songs for it. Perhaps a whole winter’s songs, perhaps not.”

And Beorc fell to singing himself, which he would when he wished not to discuss a thing.

“Master Beorc,” said Caoimhin, annoyed, but Niall took up the other end of the rail and held it in place in silence, so Caoimhin, scowling still, knelt to set the pole.

That evening there were indeed songs at the table in the yard, beneath the stars. The harper played for them on his plain and battered harp, delighting the children with merry songs made just for them. But there were great songs too. He had made one of the great battle at Aesclinn; he sang of the King and Niall Cearbhallain, while Niall himself looked only at the cup in his hands, wishing the song done. There were tears in many eyes as the harper sang; but Beorc and Aelfraeda sat hand in hand, listening and still, keeping their thoughts to themselves; and Niall sat dry-eyed and miserable until the last chord was struck. Then Caoimhin cleared his throat loudly and offered the harper ale.

“Thank you,” the boy said—Fionn, he called himself, and that was all. He drank a sip and struck a thoughtful chord, and let the strings ripple a moment. “Ah,” he said, and after a moment let the music die and took up the ale again. He drank and looked up at them with the sweat cooling on his brow, and then gave his attention to the harp again.

“ The fires are low

The breezes blow

And stone lies not on stone.

The stars do wane

And hope be vain

Till he comes to his own.”

Then a chill came on Niall Cearbhallain, and he clenched tight the cup in his hand, for it meant the boy King.

“That song,” said Caoimhin, “is dangerous.”

“So,” said the harper. “But I am wary where I sing it. And a harper is sacred—is he not?”

“He is not,” said Niall harshly and set his cup down. “They hanged Coinneach the king’s bard in the court of Dun na h-Eoin, before they pulled the walls down.” He stood up to leave the table, and then recalled that it was Beorc’s table and Aelfraeda’s, and not his to be leaving in any quarrel. “It is the ale,” he said then lamely, and sank back into his place. “Sing something less grim, master harper. Sing something for the children.”

“Aye,” said the harper after a moment of looking at him, and blinked and seemed a moment lost. “I will sing for them.”

So the harper did, a lilting, merry song, but it struck differently on Niall’s heart. Niall looked toward Aelfraeda and Beorc, a pleading look and, receiving nothing of offense, gathered himself from his bench and went away into the dark, down by the barn, where the music was far away and thin and eerie in the night, and the laughter far.

There he leaned against the rail of the pen and felt the night colder than it had been.

“Singing,” piped a voice.

It startled him, thin and strange as it was, coming from the haystack, even if he knew the source of it.

“Mind your business,” he said.

“Niall Cearbhallain.”

A chill ran through him, that it had somehow gotten his name. “You’ve been lurking under more haystacks than this,” he said. “I’d be ashamed.”

“Niall Cearbhallain.”

The chill grew deeper. “Let me be.”

“Be what, Niall Cearbhallain?”

He shrugged aside, shivering, ready to go off anywhere to be rid of this badgering.

“Feasts at the house,” said the Gruagach. “And what for me?”

“I’ll see a plate set out for you.”

“With ale.”

“The largest cup.”

The Gruagach rustled out of the haystack and hopped up onto the rail, his shagginess all shot through with bits of straw in the dark. “This harper does not see,” said the Gruagach. “He sits and harps and sometimes it comes clear to him and most times not. Your luck has brought him here, Niall Cearbhallain. He came to you first. He is fey. He is your luck and none of his own.”

“What made you so wise?” Niall snapped, dismayed.

“What made you so blind, Man? You came here once yourself with the smell of the Sidhe about you.”

He had started to turn away. He stopped and stared, cold to the heart. But the Gruagach bounded off the rail and ran.

“Come back!” he called. “Come back here!” But the Gruagach never would. He was lost into the dark and gone at least until he came for his cakes and ale.

There was a quieter gathering very late that night, in the hall by the fireside where the harper sat half-drowsing with ale, the harp clasped in his arms and the firelight bathing his face with a kindly glow. Beorc and Aelfraeda, Lonn and Sgeulaiche and Diarmaid, a scattering about the room; and Caoimhin was there when Niall came straying in, thinking the hall at rest.

“Sir,” said the harper, who rose and bowed, “I hope there was no distress I gave you.”

“None,” said Niall, constrained by the courtesy. He bowed, and addressed himself to Aelfraeda. “The matter of the cakes—may I see to it?”

Aelfraeda gathered herself up and everyone was dislodged. “The harper’s tired,” she said. ‘To bed, to bed all.” She clapped her hands. Beorc moved and the rest did, and the drowsing harper blinked and settled the more comfortably into his corner.

Niall filled the cup himself and took the plate of cakes out on the porch. “Gruagach,” he called softly, but heard and saw nothing. He went inside, as all the house was settling to their rest; and Scaga who had made himself inconspicuous in the corner came out of his hiding.

“Enough,” said Niall. “To bed.– Now.” So Scaga fled.

But over Caoimhin he had no such power. Caoimhin remained, watching him, and the harper’s eyes were on him.

“Cearbhallain,” said the harper quietly.

“And has hetold you? And how many know?”

“I knew at the table. I have heard the manner of your face.”

“What, that it is foul? That it is graceless?”

“I have heard it said you are a hard man, lord. Among the best that served the King. I saw you once—I was a boy. I saw you stand at table tonight and for a moment you wereCearbhallain.”

“You are still a boy to my years,” Niall snapped. “And songs are very well in their moment. In hall. You were not at Aescford or Aesclinn. It stank and it was long and loud. That was the battle, and we lost.”

“But did great good.”

“Did we?” Niall turned his side to him, taking the warmth of the dying fire on his face, and a great weariness came on him. “Be that so. But I am for bed now, master harper. For bed and rest.”

“You gather men here. To ride out to Caer Wiell. Is that your purpose?”

It startled him. He laughed without mirth. “Boy, you dream. Ride with what? A haying fork and hoe?”

The harper reached beside him at the bricks of the fireplace, pulled forward an old sheath and sword.

“Dusty, is it not?” said Niall. “Aelfraeda must have missed it.”

“If you would take me with you—lord, I can use a bow.”

“You are mistaken. You are gravely mistaken. The sword is old, the metal brittle. It is no good any more. And I have settled here to stay.”

A pain came over the harper’s face. “I am no spy, but a King’s man.”

“Well for you. Forget Caer Wiell.”

“Your cousin—the traitor—”

“Give me no news of him.”

“—holds your lands. The lady Meara is prisoned there, his wife by force. The King’s own cousin. And you have settledhere?”

Niall’s hand lifted and he turned. The harper had set himself for the blow. He let his hand fall.

“Lord,” Caoimhin said.

“If I were the Cearbhallain,” said Niall, “would I be patient? He was never patient. As for taking Caer Wiell—what would you, harper? Strike a blow? An untimely blow. Look you, look you, lad—Think like a soldier, only once. Say that the blow fell true. Say that I took Caer Wiell and dealt all that was due there. And how long should I hold it?”

“Men would come to you.”

“Aye, oh aye, the King’s faithful men would come—to one hold, to the Cearbhallain’s name. And begin battle for an infant king—for a power before its time. But An Beag would rise; and Caer Damh—no gentle enemies. Donn is fey and strange and no trust is in them if there is no strong king. Luel’s heart is good but Donn lies between, and Caer Damh—No. This is not the year. In ten, perhaps; in two score there may be a man to crown. Maybe you will see that day. But it is not this day. And my day is past. I have learned patience. That is all I have.”

For a moment all was silence. An ember snapped within the hearth. “I am Coinneach the king’s bard’s son,” the harper said. “And I saw you at Dun na h-Eoin once, in the court where my father died.”

“Coinneach’s son.” Niall looked at him, and the cold seemed greater still. “I had not thought you lived.”

“I was with the young King—King he is, lord—until I took to the roads. And I have lodged under hedges and among old stones and now and again in Luel and Donn, aye, and An Beag’s steadings too, so never name me coward, lord. Two years I have come and gone and not all in safety.”

“Stay,” Niall said. “Lad, stay here.There is no safety else.”

“Not I. Not I, lord. This place is asleep. I have felt it more and more, and I have slept places round about Donn that I would never cross again. Leave this place with me.”

“No,” Niall said. “Neither Caoimhin nor I. You will not listen. Then never think to come back again. Or to live if you once pass the gates of Caer Wiell. Have you thought how much you could betray?”

“Nothing and no one. I have taken care to know nothing. Two years on the road, lord. Do you think I have not thought? Aye, since Dun na h-Eoin I have thought and come on this journey.”

“Then farewell, friend’s son,” Niall said. “Take my sword if it would serve you. Its owner cannot go.”

“It is a courteous offer,” the harper said, “but I’ve no skill with swords. My harp is all I need.”

“Take or leave it as you will,” Niall said. “It will rust here.” He turned away and went toward his own nook back along the halls. He did not hear Caoimhin follow. He looked back. “Caoimhin,” he said. “The lad has a long way to travel. Go to bed.”

“Aye,” said Caoimhin, and left him.

The harper left before the dawn—quietly, and taking nothing with him that was not his—“Not a bit to eat,” Siolta mourned, “nor anything to drink. We should have set it out for him, and him giving us songs till his voice was gone.” But Aelfraeda said nothing, only shook her head in silence and put the kettle on.

And all that morning there was a heavy silence, as if merriment had left them, as if the singing had exhausted them. Scaga moped about his tasks. Beorc went down to the barn in silence and took Lonn and, others with him. Sgeulaiche sat and carved on something Sgeulaiche understood, an inchoate thing, but the children were out of sorts from late hours and sulked and complained about their tasks. And Caoimhin who had gone down with Beorc never came to his work.

So Niall found him, sitting on the bench at the side of the barn where he should have gathered his tools. “Come,” said Niall, “the fence is yet to do.”

“I cannot stay,” said Caoimhin, so all that he had feared in searching for Caoimhin came tumbling in on him; but he laughed all the same.

“Work is a cure for melancholy, man. Come on. You’ll think better of it by noontime.”

“I cannot stay any longer.” Caoimhin gathered himself to his feet and met his eyes. “I shall be taking my sword and bow.”

“To what use? To defend a harper? What will he be saying to An Beag along the way?—Pray you never notice that great armed man: he set it on himself to follow me? A fine pair you would be along the road.”

“So I shall follow. A winter I said I would stay. But you have stolen a year from me. The boy was right: this place is full of sleep. Leave it, Cearbhallain, leave it and come do some good in the world before we end. No more of this waking sleep, no more of this place.”

“Think of it when you are starved again and cold, or when you lie in some ditch and none to hear you—O Caoimhin! Listen to me.”

“No,” said Caoimhin and flung his arms about him briefly. “O my lord, one of us should go to serve the King, even if neither sees his day.”

Then Caoimhin went striding off toward the house, never looking back.

“Then take Banain,” Niall cried after him. “And if you have need then give her her head: she might bring you home.”

Caoimhin stopped, his shoulders fallen. “You love her too much. Give me your blessing, lord. Give me that instead.”

“My blessing then,” said Cearbhallain, and watched him go toward the house, which was as much as he cared to see. He turned. He ran, ran as he had run that day long ago, across the fields, as a child would run from something or to something, or simply because his heart was breaking and he wanted no sight of anyone, least of all of Caoimhin going away to die.

He fell down at last high upon the hillside among the weeds, and his side ached almost as much as his heart. He had no tears—saw himself, a grim, lean man the years had worn as they wore the rocks; and about him was the peace the hillside gave; and below him when he looked down was the orchard ripe with apples, the broad meadow pastures, the house with the barn and the old oak. And above him was the sky. And beyond the shoulder of the hill the way grew strange like the glare of rocks in summer noon, the sheen of sun on grass stems, so that his eyes hurt and he looked away and rose, walking along the hill.

Then a doubt came gnawing at him, so that he passed along the ridge looking for some sight of Caoimhin, like a man worrying at a wound. But when he had come on the valley way he saw no one, and knew himself too late.

“Death,” said a thin small voice above him on the hill.

Niall looked up in rage at the shaggy creature on the rock. “What would you know, you croaking lump of straw? Starve from now on! Steal all I have, creeping thief, and starve!”