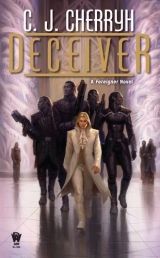

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

After lunch, Bren thought in some disquiet. Ilisidi had done more than take over the estate. She had taken over communication with the village. And, one hoped, security for the coming and going involved.

“I shall go to my rooms and have my thoughts in order, then,” Geigi said. “One will expect the Grandmother of the Edi at whatever time she chooses to visit. My gratitude, aiji-ma, nandi.” He gathered himself from his chair, moving slowly, looking, at the moment, very sad.

One wished one could do something. But what could be done—seemed out of the paidhi’s hands at the moment.

So for the next while, they had one very worried Baiji down in the basement with a stack of paper and a pen. They had Geigi relaxing in his quarters with a plate of teacakes and a pot of tea. They had the dowager busy phoning Shejidan and sending messages to Najida andover to Kajiminda, apparently couriered by the village truck.

Soc it was a chance for the paidhi-aiji to get to his office and do some fast research in the massive post-coup data files he had gulped down months ago and had only moderate time to sort throughc what lord was currently in charge of what province, since the Troubles; what was the situation of the clan and family, and what were the affiliations and associations– all these things—notably regarding the west coast and the Marid. In a land that knew no hard and fast boundaries, among people who viewed overlap of associational territories as entirely ordinary, allegiances shifted in total disregard of physical boundaries.

Impossible to draw any meaningful atevi map except in shades of those relationships, in which the likelihood of various families having ties outside, say, a province, increased markedly as one approached a quasi-border—and so did the likelihood of various families having bloodfeuds on the other side of the almost-border.

The west coast was a case of shells within shells within shells, all overlapping circles of territory and past agreements. The whole district had a long history of warfare, sniping, assassinations, political marriages, and simple trade-marriages, where two families made arrangements for business association in the only coin that lasted centuries: blood-ties. Marriages.

Exactly what Ilisidi proposed for Baijic and what Geigi was interested in, not only for Kajiminda, which he ruled; but also for Maschi clan. The current head of Maschi clan was Pairuti. That, Bren knew.

Records confirmed that Pairuti had come to formal court in Shejidan during the days when Murini was in power, paying the expected visit to new authority, and probably really worried about getting back home alive.

Pairuti had come to Shejidan when Tabini had come back to power, paying the expected courtesy, and had probably really worried about his life then, too. Pairuti had not written a letter to Shejidan when Geigi’s sister had died—had let Baiji step right into the lordship with never a protest ora request for external review of the succession, during Murini’s rule; evidently he had simply approved the inheritance.

It would have been so useful if Pairuti had had the sense and the nerve to do something, considering Lord Geigi stranded in space and no shuttles flying, with a spoiled brat about to take over the administration of Kajiminda, in its strategic location.

But then, Pairuti wasc over ninety years old, with four sons and two daughters by several marriagesc all mature and married.

More searching of the database. Two sons by a wife from the northern clans. One daughter by a remote relative of the Taibeni Ragi, central district. One daughter and a son by a local wife, out of the Koga, a Maschi subclan, no useful power games there, at least for the Maschi, unless the game was stabilization or paying off a local debt. Maybe it had been honest attraction on Pairuti’s part. But interspersed between the Ragi wife and the Koga, back when Geigi himself had had a marriage into the Marid, Pairuti, then in his seventies, had contract-married one Lujo, daughter of Haiduni, in the Senjin Marid.

The Senjin. Neighbors to the Farai, who were currently sitting in hisapartment, pending Tabini throwing them outc

Geigi himself, in the old days, had had very troublesome associations: had been an associate of several people in the Samiusi districtc had had a wife out of the Samiusi clan of the Taisigin Marid, a woman—the names floated past, jostling old memory—affiliated with Hagrani clan of the Taisigi, who was (he needed no help to remember this one) related to the current bad piece of business in the Marid—Machigi, who was clan-head of the Taisigi and lord in Tanaja at age twenty-two.

Thatwas a coupling of power, intelligence, and raw inexperiencec bad business, which Geigi had shed very definitively. Geigi had fallen out with the Marid when he discovered his Samiusi wife had been playing games with the Kajiminda books and trying to bankrupt him. Thathad driven Geigi straight into Tabini’s camp, where he had stayed ever since.

God knew what Pairuti’s Marid wife had been up to on the other side of the shared quasi-border, what kind of financial mess and political tangle Maschi clan proper had gotten into because of that tie—

And it was a fairly delicate matter to bring up with Geigi. Forgive me, Geigi-jic when you divorced your wife, what did you advise Pairuti to do about his?

Pairuti hadn’t divorced the woman. The contract had eventually ended and she had gone home to her clan. But a lordly marriage—servants came into the household with the arriving spouse, and melded with household staff, and got children of their own, and lines mixed, and connections lasted for generations. It wasn’t just the lords that needed watching.

There’d just been too much going on for the aishidi’tat as a whole to keep a very close eye on the Maschi, in their critical position. Geigi, who was actually far more powerful in the aishidi’tat than Pairuti, had probably been wielding his worldwide influence with a little delicacy when it came to dealing with his own rural clan. Geigi hadn’t involved himself in Maschi affairsc had drawn his servant staff from among the Edi, who did notmarry outsiders, or much associate with them. Even when Geigi had had a Marid wife, infiltrating his staff would have been very, very hard for the Marid.

Not so, with Pairuti.

Most troublesome of all, the Maschi clan lord hadn’t given Baiji any help or advice at all, to hear Baiji tell it—whether thinking that it was Geigi’s business who ruled in Kajiminda– or just being scared of Baiji’s suitors.

They needed to know. They needed either to support Pairuti, and help him clean house—or to deal with Pairuti’s situation. An aging lord, perhaps having accumulated a lot of problems on staff—they could sit here at Najida trying to fix Kajiminda, which had ceased to be a threat—but ignoring Pairuti, given what they had learned, that was a potential problem.

He jotted down the text of a letter:

The paidhi-aiji, neighbor to Kajiminda at Najida, newly arrived in his estate after long absence, wishes officially to extend salutations to the clan of his neighbor Geigi of the Maschi.We are informing ourselves and Tabini-aiji of the dangerous situation that has placed Kajiminda in difficulty and would be interested to hear the opinions of the lord of Maschi clan regarding the situation.We rejoice in the safe return of Lord Geigi to rule Kajiminda and will be assisting him wherein we are useful.We wish to arrange a meeting with Maschi clan as soon as possible. Thatshould scare hell out of the old fellow, if he had been playing both sides of the table. Let him wonder what had happened to Baijic if his wife’s former staff connections didn’t tell him.

So the Marid had made their move: Machigi, the twenty-two-year-old head of the Taisigin Marid, had used his neighbors like chess pieces, and likely had inherited the game from his predecessors.

Machigi had assumed power at twenty-one, meaning that he had notarranged Pairuti’s marriage, but he hadcome into his office with Murini’s rise—had fairly well come into his power right when Murini had taken over in Shejidan.

So he would have been directing Marid moves, and if somebody had intended Murini’s assassination when he ceased to be useful, that would be Machigi.

Another small search, instant to the screen.

Guild reports on Machigi agreed he dominated his advisors and not the other way around. The latest report said two of his advisors were now dead, who had mildly argued against him.

That seemed fairly definitive, didn’t it?

Machigi had been in power during the probable assassination of Geigi’s sister, the courtship of Baiji, the assassination of the girl Baiji had claimed to be interested in—and her whole family—the establishment of Marid Guild in Separti and Dalaigi Township, the takeover of Kajiminda, the attempt on the paidhi’s lifec and probably collusion with the Farai in keeping the paidhi out of his Bujavid apartment, while setting up in that apartment at least to spy on Tabini, if not to attempt to assassinate him.

For twenty-two, young Machigi was developing quite a record.

The paidhi-aiji’s proper business was to interpret human reactions to atevi actions, and to let Tabini-aiji determine policy and do the moving. But paidhi-aiji was not all he was. Tabini-aiji had appointed him Lord of the Heavens andLord of Najida: and Najida was under seige.

He found himself no longer neutral, no longer willing to support whatever authority turned up in charge on the mainland. He had started with a slight preference, and it had become an overwhelming one. He had long ago stopped working for Mospheiran interests. Now he moved a little away from Tabini-aiji. He wanted certain people currently under this roof to stay alivec and he had to admit to himself his reasoning was not all cold-blooded, logical policy. He caredabout certain people. He believed—at least on some objective evidence—that their survival was important to policy. But caredand believedwere not words his professional training encouraged. He walked cautiously around these affections, which atevi would not even understand, outside the clan structure. He examined them from all sides, examined his own motives—he didn’t trust his loss of objectivity, and he didn’t at all trust his personal attachment to the individuals involvedc

But, damn it, if anything happened to certain people he’d—

He wasn’t up to filing Intent on Machigi. He didn’t want to put his security team in that position, for one thing: he didn’t have the apparatus necessary to take on a provincial lord who had five tributary regions attached to him, each with its own force of Assassins. It would be suicide—for the people he was most attached to. And that course of action wouldn’t help the situation.

And he wasn’t wholly sure he wanted Tabini-aiji to file Intent on his behalf, either, even if he could manipulate the situation to make that happen. Going after Machigi in an Assassins’ war would be messy. It would cost lives, as things stood now, and Machigi had far too many assets. Those had to be peeled away first.

Add to that the fact that Tabini was relying on a new security team—good men; but Tabini had lost the aishid that had protected him literally from boyhood, a terrible, terrible loss, on an emotional scale. He had lost a second one, which had turned out unreliable. The emotional blow thathad dealt someone whose psyche resonated to loyalties-offered and loyalties-owed, he could only imagine.

So Tabini himself was proceeding carefully since his return to powerc trusting his new team, but only step by step figuring out how far he could rely on them, both in how good they were, and how committed they were. Extremely committed, Bren thought; but Tabini might be just a little hesitant, this first year of his return, to take on the Marid, who had defied him from the beginning of his career.

Caution wasn’t the way he was used to Tabini operating. Reckless attack wasn’t the way Tabini was used to the paidhi-aiji operating, either. Of all people in the world—the paidhi was not a warlike soul. But the fact was, of persons closest to Tabini, the ones with aishidiin that absolutely werebriefed to the hilt and capable of taking on Machigi—amounted to the paidhi-aiji and the aiji-dowager.

God, wasn’t thata terrifying thought? He was grateful beyond anything he could say that Tabini, lacking protection, hadn’tyanked Banichi and Jago back to his own service. He couldn’t imagine the emotion-laced train of atevi thought that had persuaded Tabini notto do that—well as he knew the man, when it got down to an emotional choice, he couldn’timagine and shouldn’t ever imagine he did. Just say that Tabini hadn’t taken them. Tabini had left the paidhi-aiji’s protection intact and taken on a new aishid, himself. Man’chi, that sense of group and self that drove atevi logic, had been disrupted in the aiji’s household, and had to be rebuilt slowly, along with trust. And until that could happen—Tabini was on thin ice, personally and publicly. Tabini neededhelp. Tabini was, damn it, temporizingwith minor clans like the Farai, when, before, he would have swept them away with the back of his hand.

Meanwhile, starting during Murini’s brief career, Machigi had almost won the west coast, a prize the Marid had been pursuing for two hundred years. He’d come damned close to doing it, except for the paidhi-aiji taking a vacation on the coast. And now things were happening—the Edi organizing and gaining a domain, for one thing—that were not going to make Machigi happy.

Damned sure, Machigi was going to do something—and they were notstrong, here. Tabini’s organization was weakened. The paidhi-aiji was understaffed, always, and the aiji-dowager was operating in a territory completely foreign to her, taking actions she’d wanted to take for decades, but risking herself and the whole Eastern connection to the aishidi’tat.

At least Geigi had returned to the world to knock heads. He hadn’t come down with his full security detail either, but whatever operations the Marid had been undertaking to draw Maschi clan into its own orbit were going to suffer, now that Geigi’s feet were back on the ground, and that posed a threat to Machigi’s plans—to his life, if they took him down. Marid leaders did not retire from office.

All hell was going to break loose, was what. And there was no way the paidhi-aiji could request a major Guild action in support of his position. Tabini might not be eager to get himself visibly involved in this venture—he had a legislative session coming up in very short order, and likely didn’t want to involve himself in Ilisidi’s controversial solution for the west coast– even if he personally wanted to agree with her.

So it devolved down to theirproblem. They had to solve it with the assets they had packed into Najida estatec while Machigi had the whole South to draw on, probably including every member of the various Guilds who had too enthusiastically joined Murini’s administration. The various Guilds’ leadership had suffered in a big way during Murini’s takeover, from politically quiet ones such as Transportation and Healing, to politically volatile ones like the Messengers and, God knew, the Assassins. The way Murini’s people had purged the Guilds, the Guilds’ former leadership now being back in power had purged Murini’s people out of their ranks, and those people had run for protection to the one district that had supported Murini. The South. The Marid.

Machigi. Who consequently might be able to put into the field as many assets as Tabini-aiji.

Noc he didn’t want to challenge that power to a personal shooting match. No more than Tabini did.

Not yet.

He sat, elbows on the desk, with his hands laced together like a fortress.

One unlikely force had sat like a rock for centuries in the tides of Marid ambition: the displaced peoples of the island of Mospheira; the Edi, and the Gan. And the dowager—God, that woman was shrewd—had offered that force a prize it had never thought it could win.

And offered it with real credibility.

A knock at his door. Jago came in.

“The Grandmother of the Edi is on her way, Bren-ji. We are not interfering, but we are covertly watching, with Cenedi’s cooperation.”

“Good,” he said. “Lord Geigi?”

“Is aware.”

Which meant his security staff had informed Geigi’s.

Bren got up and picked up his coat. Jago assisted him to put it on. She was in house kit, augmented, however, by a formidable pistol that rode low at her hip: the ordinary shoulder holster might be under the jacket, but that thing looked as if it could take out the hallway. “House rules: we respect her security.”

“Yes,” Jago said. And added, in a restrained tone: “Barb-daja is asking to go into the garden at this moment.”

“No,” he said. Two people in the house were notin the security loop, and didn’t have staff to inform them there was a major alert going on. The movement of the Edi lady was a serious risk. “Tell Ramaso to attach two senior staff to my brother and Barb-daja. They should not let them out of their sight—and they should stop anyone who attempts to exit the house.”

“Yes,” Jago said with some satisfaction, and plucked his pigtail and its ribbon free of his collar.

He took the time to fold up his computer, lastly, and put his notes away, and locked the desk, not against hisstaff—just his personal policy, and precaution, under present circumstances. They’d had the house infiltrated once, and he didn’t take for granted it couldn’t happen twice.

Jago said, head tilted, pressing the com into her ear, “The Edi are arriving.”

Time to go, then.

8

« ^ »

Only the chief lords in a gathering sat to meet, in Ragi culture. Among Edi there was no such distinction. Every person present was entitled to speak on equal footing; so the household had prepared the room with every chair that could be pressed into service—including one large enough for Lord Geigi’s massive self, and three others small enough that the aiji-dowager, Cajeiri, and the paidhi-aiji would not have their feet dangling—Bren had made the point himself with staff about seating humans, and staff had cannily and tactfully extended the provision to the diminutive aiji-dowager without a word said.

The Grandmother of the Edi, whose name was Aieso, was a lady of considerable girth, but like most Edi folk, too, small of stature. The weathering of years of sun and wind and the softness of her well-padded body allowed deep wrinkles below her chin. She was a plump, comfortable lady—until one looked in her eyes. And no knowing which of the two, she, or the dowager, was older, but one suspected that honor went to Ilisidi.

Aieso sat, as Geigi rose and came to offer a little bow. “Aieso-daja. We have met many years ago. I am Geigi of the Maschi.”

Aeiso regarded him with a little backward motion of her head, as if she were bringing him into focus. “Lord Geigi. Many years we have been allies.”

“One is honored,” Geigi said. “And I am extraordinarily appreciative that you were willing to come up from the village.”

The Grandmother nodded, rocking her whole body amid her fine embroidered shawls. “And have you come back to stay now, Maschi lord?”

“At least to finish my usefulness here, honored lady. I have come back to remove my nephew from any position ever to deal with the Edi, and in the interests of setting the tone of this meeting, let me say at the outset that I wish to make thorough amends to my neighbors and to my staff before I go back to space.”

“Huh.” The Grandmother made a low sound in her throat. “ Willit change, Maschi lord?”

“The understanding of the treaty will not change, one hopes,” Geigi said levelly. “Some things, however, nandi, ought to change. We are not in disagreement with the aiji-dowager’s proposal. And with that said, one hopes this will be a productive and harmonious meeting of old allies.” Lord Geigi bowed, waiting not at all for a comment from the lady of Najida, and went over to resume his own chair, leaving the canny lady nodding thoughtfully to herself, with her hands folded on her lap.

Tea went the rounds. And it took every cup and every pot available in the house, considering the Najida Grandmother’s contingent. There was a decided dearth of Guild security in the room: Banichi and Jago had stationed themselves just outside, in favor of Cenedi and Nawari, and Cajeiri’s young guards were also outside. Geigi’s bodyguard, however, most directly in need of briefing, were standing in the far corner of the room.

“Welcome to our Edi guests,” the dowager said, when the tea service was done to satisfaction. “Welcome to Lord Geigi of Kajiminda, who is residing here at Najida for safety’s sake, until something can be done to guarantee Kajiminda’s security. We hope present company can assist in that matter. Gratitude to the paidhi-aiji, our host for this auspicious meeting. We have spoken to our grandson, meanwhile, and he has received news of our proposals without comment as yet, but he is listening with interest. Lord Geigi may have a comment on this.”

“One would wish to speak, yes, aiji-ma,” Geigi said, still seated. “And one can only regret the mismanagement of my nephew in his care of Kajiminda, and one must say—my own acceptance of his lies as the truth. He has been dismissed from his honor and remains under close guard. He will not return to Kajiminda under any circumstance and only remains in this district because he may still hold useful information. Tell me, neighbors, nand’ Aieso, is there any news of my staff? Are they safe? One understands this may be a veiled matter, but one earnestly wishes to hear good news. One would instantly offer them their jobs back, if they could be persuaded to return. Certainly, for those who may have retired during my absence, under a reprehensible administration of the estate, one foresees issues of recompense and pensionc all things I would wish to see to.”

“Regrettably,” Aieso said, “certain ones have died violently, Maschi lord. Others have gone to Separti Township. Some few are in Najida village and some will reside in your own village, when you go there. Certain ones, indeed, have grown old in your service and have not been fairly dealt with by your nephew.”

“Tell me these cases and ask them to come to me for redress, nandi, one earnestly asks this.”

A nod from the lady, a lengthy and meditative nod. “You have a good reputation, Maschi lord. Your clan has not, at the moment, and your sister and your nephew have not. Your surviving staff is waiting for word, waiting for the Ragi to clear out of Kajiminda. When you go to your own house, you will have staff and you will have protection enough in the fields round about. Dare you rely on it?”

“One is greatly relieved to hear so,” Geigi said. “And one has no hesitation in relying on it. These four Guild will still attend me. These men—” He indicated the Guildsmen in the corner. “These men are attached to me, of long standing. Never be concerned about their man’chi. It is to me.”

A long, slow intake of breath on the Grandmother’s side– a difficult issue, and one would suspect the Edi would like to detach Geigi from any Guild presence at all, but Geigi’s firm statement indicated this would not happen.

“The matter of an Edi house,” Geigi said further, “I strongly support. One assumes the Grandmother of Najida would be in charge of such an establishment—and should you, nandi, at any time wish to be my guest in Kajiminda until this is a reality, you are welcome. Kajiminda estate will welcome you as resident. Kajiminda will remain Maschi, so long as the treaty stands, but will cede all the peninsula south of the brook, all those lands and the hunting and fishing in them—it does this unconditionally, looking forward to the construction of an Edi estate.”

It was an astonishingly generous offer. It stripped Kajiminda of all income except a little hunting and a little fishing, and, most importantly, put Kajiminda village itself under Edi control. There was a quiet buzz of interest in the room.

And the paidhi asked himself—was it legal? CouldGeigi do that, without the authority of his clan lord? Never mind he was the holder of Kajiminda—did he have the authority to sign part of it away?

Muted tap, from Ilisidi’s cane.

“We also support Lord Geigi’s offer.”

More comment in the room, people perhaps asking themselves the same question. And two more taps of the cane.

“Cenedi,” Ilisidi said sharply, and Cenedi walked from behind her chair to the midst of the gathering.

“A word from the Guild that protects the aiji-dowager,” Cenedi said, “and from others of the Assassins’ Guild involved here at Najida, regarding our intent and purpose. We will bring armed force where necessary to protect the lords of the aishidi’tat. We will notmove against forces that may be defending Edi territories. We count such forces as allied to the lord of Kajiminda according to a treaty approved by the aishidi’tat. Our Guild supports Lord Geigi’s decision to rely on local force, and will cooperate.”

Technical, but that was major, even speaking only for Guild presently in the area. The Assassins’ Guild had historically taken a very dim view of militias and irregularsc and Ilsidi’s chief of security promised cooperation with the Edi.

“Nadiin,” Cenedi said then, and four more Guild walked to mid-room: Geigi’s, from the station. “Nand’ Geigi’s bodyguard.”

A little bow from Haiji, the senior of that association. “We are here withour lord. We will work with Edi staff and with Guild here at Najida. Cooperation with the people of the region is our lord’s standing order.”

With which, with quiet precision, the five Guildsmen separated and went back to their places, leaving a little buzz of talk behind them.

“We invite the Edi to choose a building site,” Geigi said. “Anything is negotiable. We are at a point of felicitous change. Baji-naji, there will be adjustments and perfection of our understandings, but let us establish that there will be an Edi seat in this district, whether or not the lordship is declared this year or the next. You will begin to make it inevitable, and havinga place to which communications may come and from which statements are understood to be official—the aishidi’tat understands such things as important. To what degree you use this place for your purposes, or in what way you use it, or how you sanctify it—that will be Edibusiness.”

There had been a lukewarm response up to that last sentence. But Geigi, whose whole business on the station was maintaining a smooth interface between atevi and humans, and making things work, had just delivered something that did matter, deeply, with that last how you sanctify it. Old Aeiso rocked to and fro and finally slapped her stout hands together, twice and a third time.

Feet stamped. Faces remained impassive, but the racket had to be heard throughout the house; and it went on until Aieso got up and wrapped her shawls about her.

“Will it be agreed?” she asked, and at a low mutter from her people, she nodded, folded her arms tightly and looked at Geigi and at Ilisidi, and straight at Bren. “Kajiminda will be under our protection, the same as Najida, and our hunters range as far as Separti Township and report to us. Guild are welcome under the direction of our allies Lord Geigi and Lord Bren and the Grandmother of the Ragi.”

That was a damned major concession, and rated an inclination of lordly heads.

“Najida hopes to be a good neighbor, nandi,” Bren said.

“So with Kajiminda,” Geigi said.

“The Grandmother of Najida knows our disposition,” Ilisidi said, and Aieso nodded, rocking her whole body.

“So. We will walk,” Aieso said, “we shall go walking seaward of the brook on Kajiminda, Maschi lord, and see if there is a spot the foremothers favor.”

“Indeed,” Geigi said. Bren only remotely construed what Aieso intended, but one recalled the monuments of the Edi on the island of Mospheira, the monoliths incised with primitive, slit-eyed, slit-mouthed faces and the hint of folded arms: the Grandmother Stones, left behind—one could only imagine the trauma. Such stones stood on an isle to the north, in Gan territory. Ragi atevi, inveterate tourists, who would undergo amazing hardship to view something historic or scenic, were not welcome there, and, in turn, pretended no such stones existed. They were noton the official maps.

One thought of those stones, in territory where no outsider was welcome.

One gathered the old woman would, indeed, go hiking about the peninsula, likely with a contingent of her people—testing Geigi, among other things. Maybe establishing lookouts and arrangements of their own, for future defense.

It would be a far walk for the old woman. And a hard one. By the placement of such statues, the Edi favored difficult places.

“Najida would lend the bus for transport,” Bren said, “should you wish, nandi.”

That won a soft chuckle from Aieso, who seemed in increasing good humor, even brimming delight. “The old truck will suffice us, Najida-lord. But mostly we shall walk.” And to Ilisidi: “Grandmother of the Ragi, speak to your grandson and advise him what we have agreed. Advise him when we walk in Kajiminda, we will assure our own safety.”

Ilisidi nodded. “We wish you well, Grandmother of the Edi.”

Aieso gathered her shawl about her. Her company stood up, and Bren did, and so did Geigi and Cajeiri. There were bows on both sides, a second nod from Ilisidi, who accepted Cenedi’s arm to rise, slowly, using her cane, and the visitors quietly followed Aieso out, leaving a room full of slightly disordered chairs and a portentous silence.

God, Bren thought, done was done. The Edi were going to pick out a building site on what amounted to their half of Kajiminda Peninsula, and one could figure, up on the north coast, their fellow exiles from Mospheira, the Gan, were going to start making their own demands on the aishidi’tat for full recognition and, one hoped, membership in the aishidi’tat– thatpoint was one on which he intended to work hard.