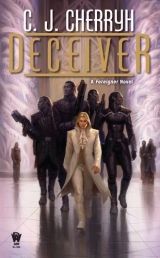

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“One is appalled,” Bren said. “One is utterly appalled, aiji-ma.”

“Ha. So you agree.” The ancient eyes that had seen a good deal of treachery in a lifetime sparked fire. “And we shall not sit here inert.”

“ ’Sidi-ji,” Geigi said. “ ’Sidi-ji. What can one say to this?”

“That you will take action, Geigi-ji. That you have been a long time removed from this arena, and your presence here as lord of Sarini Province can only be salutary.”

“One had planned to return to the station, but—”

“Oh, you shall. You must. You have done far too well in that position. Considering the situation we face, with foreigners apt to arrive, we need you there. But certain things need your attention.”

“Absolutely, aiji-ma. Whatever one can do—”

“If my grandson steps in and takes action, it is another heavy-handed Ragi seizure—such an unhappy history on this coast. If the Guild does—the same. Things here are delicate. You appreciate it in unique ways. And coming at proof may not be easy. Lord Pairuti may have destroyed recordsc”

Geigi held up a finger. “May have. But I would wager not, aiji-ma. Not that man. His disposition is compulsive—a passion for details. He will have them. And I can get them. I shall need to take back Kajiminda with some dispatch. Clearly, so doing, I shall need to interview certain of my own clan. Which makes my calling on Pairuti obligatory. He will expect it. He will be in a dither to hide the records, but he will not destroy them, not that man.”

Go there? Good God.

“We are understaffed, Geigi-ji,” Bren protested.

“We have taken measures in that direction, nandiin,” Ilisidi said smugly. “We will haveforce at our disposal—granted my grandson understands our position. He will notpermit Lord Geigi to come to grief. He may fuss about the situation. But he will move to protect the treaty that binds the coast to the aishidi’tatc and you, Geigi-ji, are its living embodiment. He willmove.”

Read: Tabini hadn’t agreed to Ilisidi’s demands. Tabini hadn’t jumped to relocate his forces from Separti. He hadn’t come rushing to Ilisidi’s conclusion, perhaps, or he had something else going on that he wasn’t happy to leave.

Which could mean there were complications.

Najida’s perspective on the immediate threat, however, were different than Tabini’s. If Pairuti was colluding with the Marid, Najida was staring up the barrel of a gun. Problems could come at them right down the airport road. Or arrive en masse by train.

And Tabini, mind, had just yesterday left his son and heir andthe aiji-dowager inthis position.

Damn, he didn’t like it when Tabini turned as inscrutable and ruthless as his grandmother. Especially when he and people he cared about were in the target zone. He had to get Toby and Barb out of the harbor, as early as possible. He’d liketo ship Cajeiri and his young company back to Shejidanc but that meant exposing the movement in Najida. They’d had their chance to get Cajeiri moved out—and his father had left him behind, perhaps—dared one even think it—as an intentional proofof his lack of alarm?

“We need the help of the Edi, aiji-ma,” he said. “We need everything they can bring to bear.”

“Oh, we shall have help,” Ilisidi said with a small, tight smile. “And so much the better if the Edi will protect the grounds here, and protect us all. I have requested it. I have asked Ramaso to relay it to the Grandmother, and I have received assurances.”

God, leave the house for a few hours and come back to war preparations.

“We shall deal with it, ’Sidi-ji.” Geigi gave a little bow, distressed of countenance, but not about to retreat, no, not with that look. “I shall do everything in my power, aiji-ma, and your recommendations, allowing me to deal with this myself, are generous. And I shall want to speak to the Edi on your staff, with your kind permission.”

“You certainly have Najida’s full support, Geigi-ji,” Bren said, “so far as lies in my hands.”

“And I shall see my nephew.” Geigi drew in a long, long breath. “The wretch. I will meet with him tomorrow after breakfast. Tell him I am here, Bren-ji; and let him stew tonight.”

It had been interesting. Interesting was what Great-grandmother would call it. Cajeiri had been just very quiet and respectful, and heard all kinds of news about the neighbors, and scary hints that nand’ Geigi was going to have a talk with his relatives inland.

The talk he meant to have with Baiji, down in the basement– thatwas one Cajeiri very much wanted to hear. He was already thinking how to get in on that interview, even if he and his aishid just had to be casually walking through the downstairs– repeatedly.

But he had been right in his approach. He and, he was sure, Jegari and Antaro, had sopped up a lot of what was going on with the seniors; and maybe Lucasi and Veijico had learned something useful, too—if Tano and Algini had been in a good mood.

So very quietly, after nand’ Bren and nand’ Geigi had left– Cajeiri paid his own little bow to Great-grandmother. “One is grateful, mani. One did learn.”

“See you stay within the house, Great-grandson. And stay within call.”

“ Yes, mani.” A second bow, a deep one, in leaving. “I shall.”

What was going on outside mani’s rooms was preparation for a formal dinner this evening, and nand’ Toby and Barb-daja insisted they were coming up from the boat, which had security and staff running about—not mentioning the ongoing process of getting Lord Geigi fully installed in his suite, which had been the security office, and fed a light late lunch—everybody in the house had already eaten—to tide him over until supper.

And Lucasi and Veijico had been in the library with Tano and Algini—who might have let them hear all of it, he supposed– glum thought—or maybe not.

He gathered his aishid in his own apartment, himself sitting by his own fireplace and its comfortably warm embers. “Sit down,” he said, “nadiin-ji.” And they took the other chairs, all four of them.

“How much did you hear?” he asked Lucasi and Veijico. “And how much did you understand?”

“We heard,” Lucasi said, “that they are hoping Edi will function in the place of the Guild in protecting this region, and that Lord Geigi intends to move into Kajiminda faster than the aiji’s Guild occupying it would like. We heard that Maschi clan leadership may no longer be reliable.”

That was certainly an aspect of it. One could gather Tano and Algini had somewhat discussed that problem in their own terms. And one also gathered Lucasi and Veijico clearly did not think Geigi was being smart.

“The Edi know everything that moves on the coast,” he reminded them. “And they are used to managing this area, nadiin-ji.”

“They failed to advise nand’ Bren there was a problem. That was wrong.”

“Talking to the Edi is a problem. You know they have a rule against talking to outsiders. Nand’ Bren has gotten past that now. So has my great-grandmother. And Lord Geigi is their lord—besides, mani is already talking about putting the Edi in charge of part of this coast. So the Edi are talking to us now. And they are part of the protection of this house.”

“They have no skill against real Guild,” Veijico said. “And should not be relied on. Your father ought to know this, nandi.”

“One is certain he will know it,” he said, annoyed at their pertness with opinions. “But the Marid Guild did notsucceed in taking this house, or in holding onto Kajiminda. So they are not as smart as they think they are. And the Edi are not doing badly.”

His older bodyguards looked more than a little offput. Then Lucasi said, “That is no measure of success, nandi. The Guild does not holdpositions. Holding positions is a lord’s business. Holding is politics, and the demonstration of power.”

Well, thatwas a recitation from some book.

“So it is my business to hold things,” he said. “And yours to take them. When I say so.”

Silence, from the troublemakers. “Yes,” Antaro said quietly. Jegari nodded. But not the other two.

Useful to know the Guild’s opinion of its uses.

“The Edi,” he said, “have done very well.”

“ Notwell,” Veijico said.

“Better than the Marid Guild,” he said. Tag. Point for his side. He liked winning an argument, too. “Some of them are dead. The Edi were smart. They sided with Great-grandmother.”

“Still, nandi,” Lucasi said, “they are irregulars.”

“They are alive,” he said, “and the Marid’s Guild have been trying to take over for years.”

“Kajiminda’s Guild has prevented it, nandi. It is notirregulars who have defended this coast.”

He liked the notion that his bodyguard would talk back to him: Cenedi talked back to Great-grandmother, and Banichi talked back to Bren. But Lucasi and Veijico were being stupid. And that made him mad.

“That was,” he said shortly, “after Kajiminda’s Guild went off and got killed in the Troubles, or never even got to Shejidan, for all we know. They died.”

“Possibly the Edi that served Kajiminda all died, too,” Veijico said. “Since they are missing.”

“Nandi,” he corrected them sharply. “You say ‘nandi.’”

“Nandi,” Veijico said.

“And you are to mean it, nadi!”

A bow of the head and noopenness of expression from her or her brother. Mani would never put up with it. They thought he had to, being a year short of nine.

“I have been in space,” he said, just as nastily. “I have been on a spaceship and on a station andthe shuttle, and I have seen people who are not atevi and not human, either, where we all could have gotten blown up. So I know things, nadiin. I have gotten myself out of trouble. And Antaro and Jegari and I all three were in a war. You were not. So you should listen.”

“We listen, nandi,” Veijico said glumly.

“You are rude.”

“ No, nandi, we are notrude. We are advising you, for your safety.”

“We do as we please, nadiin! Youdo not. Weget away with things because we are not loud about it and we do what our guards by no means expect, but also because we listenabout what is dangerous and what is not and we do not go some places. We are not stupid, nadiin! You think anybody not Guild is stupid. You think the Edi are stupid. You probably think everybody in the staff is stupid. Superior thinking, mani says, does not consist of thinking oneself superior. We think you should reconsider who is stupid.”

There was a moment of deep, uncomfortable silence.

“We stand corrected, nandi,” Veijico said coldly.

“You should,” he said. It was as good as mani could do– almost. And they had deserved it. He was still mad. Which was not satisfactory. He hated being mad. He hated having people see that he was. Face! mani would say, and thwack him on the ear until he mended his expression. Which he did—mended all the way to a tight, small smile. And got up, so they all had to.

“It will be a very formal dinner tonight,” he said, meaning whatever bodyguard attended him had to eat beforehand or after. The little dining room was going to be wall-to-wall security– literally shoulder-to-shoulder Guild, considering nand’ Bren’s little estate had so many important guests.

And maybe the boredom of standing about this evening, while Antaro and Jegari ate at leisure in the suite, would give Lucasi and Veijico enough time to think about the seriousness of the situation, and about the fact that they were in among very senior security who had earned the right to respect.

“You two will attend me,” he told them. “All day.” He planned to do his lessons, which was the most boring thing he could think of, and not to let them off. “You can stand at the door and keep an eye on things. Jegari and Antaro will be helping me with my homework.”

For the paidhi-aiji, it was a formal evening coat, light green, and freshly pressed, with only a moderate amount of lace– comfortable, a country style. It was one of Bren’s favorites, comfortable across the shoulders, unlike the court-style that was intended to remind the wearer about posture—constantly. He slipped it on and went down to the front door to welcome Toby and Barb into the house. It was an exposed walk, coming up the hill, and he breathed easier when the door opened and let them in.

“I gather Lord Geigi made it in all right,” Toby said. “We saw the bus. Fancy!”

“Everything in order,” Bren said. Toby didn’t bow. He didn’t. And they didn’t touch, in front of staff, which they always were, in the hall. “Barb. Good evening.”

“Are we proper?” Barb asked in a low voice. Toby’s lady—his own ex, which was an inconvenience—but one he was determined to ignore. And do her credit, Barb tried. Toby and Barb had come up the hill wearing good Mospheiran-style clothes– that was to say white trousers, light sweaters, Toby in blue, Barb in brown with a little embroidery, and in Toby’s case, a dress jacket, the sort one might wear to a better Port Jackson restaurant. It was as formal as two boaters got, within their own wardrobes.

“Perfectly proper,” he said, in good humor, and led them on down toward the side corridor toward the dining hall, with Banichi and Jago in attendance.

But just down toward the end of the hall, Lord Geigi exited his quarters, and they delayed to meet the portly lord and his two bodyguardsc Lord Geigi resplendent in gray and green brocade and a good deal of lace.

To Lord Geigi, surely, the mode of Barb’s and Toby’s dinner dress might be a little exotic—yachting whites weren’t the mode among the numerous humans on the station—but Lord Geigi was an outgoing fellow and went so far as to offer his hand, station manners, to the complete astonishment of the household servants standing by at the hallway intersection.

“My brother Toby and his companion Barb,” Bren introduced them both. They both knew Geigi by reputation, no question of that: but a formal introduction was due. “Lord Geigi of Kajiminda, Lord of Sarini Province, third holder of the Treaty of Aregorji, Viceroy of the Heavens and Stationmaster of Alpha Station. Nandi, my brother-by-the-same-father nand’ Toby, an associate of the Presidenta of Mospheira, and his companion Barb-daja.”

Barb and Toby had never heard the full string of titles rattled off, and seemed a little confused. Toby bowed. Barb stared with her mouth a little open.

“Very glad to meet you,” Geigi said, using very idiomatic ship-speak, as they pursued their walk toward the dining room. “A pleasant surprise, your presence here.”

“Honored,” Toby said. “Very honored, sir. My brother has always spoken extremely highly of you. One is grateful.” The latter in fairly passable Ragi.

“Well, well,” Geigi said, still in ship-speak, “and eloquence runs in the family. I do very much regret displacing you from your quarters.”

“Oh, no way, sir. We’re very comfortable on the boat. The same as being home.”

“Gracious as well.” Geigi was at his jovial best as they reached the door and he half-turned, hesitating at another arrival behind them in the hall. “And the aiji-dowager joins us.”

“Do go in,” Bren said to Toby and Barb, while Geigi’s attention and his courtesies passed smoothly to Ilisidi. Personal staff had neatly coordinated the arrivals by inverse order of rank, and the paidhi-aiji in particular did notenter the dining room after the aiji-dowager. Toby and Barb went first, least in rank; he came second, and as host and holder of the estate he took his place and bowed to Lord Geigi, who entered next, and found his chair at table, at Bren’s left.

Immediately after, Ilisidi arrived with Cajeiri—hindmost.

And what with Banichi and Jago, Cenedi and Nawari, Lucasi and Veijico, and Geigi’s guards, Saoji and Sakeimi, the wall around the dining table was solid black and armed to the teethc not that the guests present didn’t trust each other. It was the house itself that was in jeopardy: dinnertime was absolutely classic in the machimi, as the most convenient time to sneak up on a house—what with servants coming and going, everybody gathered in one place, and maybe not paying attentionc and perhaps a little buzzed with alcohol.

Their bodyguards, however, werepaying attention. Constantly.

Poison? Not in his kitchen. Not with his cook.

Not with off-duty security having their supper next door to the kitchens.

And not with a household staff that came from Najida village. He had too many eyes, too many people on alert for any intruder to get that chance.

And dinner began, first of all, with wines, fruit juices, liquor. One knew what things their guest had been in the way of missing.

“Do choose, Geigi-ji,” Ilisidi said. Ordinarily staff would seek her choices first. She gave Geigi that honor.

And Geigi chose a delicate white wine for openersc Cajeiri opting for a sparkling fruit juice.

After that, then, came a succession of courses, especially the traditional regional dishes of the season. The cook had announced a seventeen-course dinner, which, even for atevi appetites, amounted more to a leisurely and lengthy tasting event than a dinner in the usual sense. There was a constant succession of plates and dishes—fish, shellfish, game of the season, imported curd and sauces of black bean plant, greenbud, orangelle, too many to track. There could not be a utensil in the kitchen not being washed and reused. There was black bread, white bread, whole-grain and soft bread. There were three kinds of eggs; and preserves and pickles. There were gravies, light and dark. There were vegetable sherbets—palate cleansers– between the courses. Bren had had particular warning from the cook about the lime-green sherbet, and he had a servant hovering anxiously by to be absolutely certain neither he nor Toby nor Barb got into that dish, which would have probably dropped them to the floor inside the hour.

There were souffles, and patés, there were crackers, four different sorts, and there were, finally, oh, my God—desserts, from cream fruit pudding with meringue to cakes and tarts, and a thirteen-layer torte with a different icing in each level.

Bren pushed back from the table in near collapse.

“If you’d like to go back to the boat—” Bren said to Toby in a very low voice, “staff can see you down. It’s dark already. But if you would like to attend the session in the study, where we shall drink brandy, or pretend to drink it at least, and observe courtly courtesies—”

“Barb?” Toby asked.

Barb looked on the verge of pain, but her eyes had that bright, darting glitter they got at jewelry counters. She looked at the lordly company, and at him, and at Toby, all in three seconds.

“When could we ever have the chance?” she asked. And then said, quietly: “If it really isn’t an intrusion for us to be there.”

Give Barb credit—and at times he truly struggled to give his ex any credit—she really was trying to absorb the experience she and Toby had fallen into, and she was on best behavior. She’d gathered about five Ragi phrases she could use, she’d bought herself a beaded dinner gown—itself a scandal in Najida village, but he didn’t tell her that—which she was not, thank God, wearing tonight. And after she’d helped Toby sink a boat in the harbor on the night when the whole place had erupted in gunfire—he’d actually had to admit Barb had been trying through all of it. Harder still, he had to admit that her help to Toby had mattered when it counted. Tonight she’d picked up cues very well, and Toby was happy, which mattered even more.

“Wouldn’t be a problem at all,” he said. “Mind, Lord Geigi handles our language on a regular basis up on station: you’ve heard. Just don’t be too informal with him. There’s some good brandy for us—don’t touch the dowager’s brand. Or have an orange and vodka. Those things are safe.”

“I’ll just sip at the brandy,” Barb said. “God, I’m stuffed.”

“Goes twice,” Toby said, “but if we won’t be trouble, we can go down late to the boat, your staff willing.”

“They’ll be up for hours, cleaning. And someone will be on duty. You’re welcome to join us.” He wasn’t Ilisidi’s escort this evening: Lord Geigi filled that post. He saw he’d inherited Cajeiri, who hadn’t said a word this evening, not one. “Are you coming too, young sir, or will you retire?”

“I shall come, nandi.”

The dinner party broke up. The dowager and Geigi went out together. Cajeiri stayed right with him. Lucasi and Veijico stayed right with Banichi and Jago. The young lord had been amazingly proper today—one was tempted to compliment him, but one always wondered what he was up to.

Gathering the gossip, Bren rather suspected, in the legitimate way, which meant sitting with the adults and listening even to things that didn’t really interest him, in hopes of some bit of mischief he could get into.

As for Toby and Barb, they were truly overfed, and had had perhaps just a half glass too much already.

But Geigi had come in from a long, long flight, endured all manner of inconvenience for a man of his girth, met with Tabini, hopped two flights, and since had a long bus ride, a meeting with Ilisidi and now a massive supper, so one rather suspected the brandy service would not stretch on into the small hours.

“Delightful, positively delightful, Bren-ji,” Geigi said to him as they were settling in to the admittedly cramped sitting room. “I have not had such a dinner in ages!”

“You are very kind to say so,” Bren said; and took a brandy himself, if only to moisten his lips with it.

Talk ran light for the while: Cajeiri was as quiet as Toby and Barb, and Bren himself had little to say, once the dowager and Geigi took to discussing the Marid.

Now that wasinteresting. One knew, but didn’t knowthe intricacies of the Marid relationships the way Geigi did.

Geigi had himself been married to a woman of the Marid—“I committed my own folly,” was Geigi’s way of putting it, “so I cannot wholly fault my fool nephew on that point, except that when the man ahead of you has fallen into a pit, it is entirely foolish to keep walking down the same course.”

“It is what we said from the beginning, nandi,” Ilisidi said. “You were doing, yes, much the same as your nephew did in listening to the Marid; but there is a difference. You hoped to stabilize the west coast, which was in a very uncomfortable balance at the time. Your staff served you gladly; you had the confidence of the Edi, despite your unfortunate marriage, and despite your wife’s best attempts to bankrupt your fortunes. Your nephew, in these dangerous times, was more concerned with stabilizing his own fortunes—no, not even his fortunes: he is not that foresighted. His comfort. One scarcely believes young Baiji ever had a thought in which his own convenience and comfort were not preeminent.”

Geigi nodded solemnly. “One hoped he had changed. I lamented my sister’s passing—we were often at loggerheads, but she had virtues when it did notinvolve her son. And she wasmy sister.” Geigi sighed. “Marriage has been very problematic for my house, nadiin-ji. A reef on which my branch of Maschi clan may have finally shipwrecked.”

“Say no such thing!” Ilisidi snapped. “Your management will resurrect Maschi clan’s fortunes. As for heir-getting, Baijiwill produce an heir with a lady of advantageous birth, his mother will have his rearing up to fortunate seven, and then we shall simply pack him up to the station so you may have the pleasure of bringing up your nephew in a proper way.”

A little smile. “You have it planned, aiji-ma.”

“Enough of aiji-ma. ’Sidi will do, I say. Speak to me. Voice your opinion about this course.”

“I would wish my heir to grow up at Kajiminda,” Geigi said wistfully, ”and I would wish to have my nephew as far away from any impressionable child as possible.”

“Ha. Bring your nephew up to the station, then marrythe young woman I suggest, and install heras lord in Kajiminda.”

Geigi’s right brow lifted. He took a sip of brandy. “Do you have a name for this theoretical young woman?” he asked.

“We have two possibilities. But we lean most to Maie of the Calrunaidi. A brilliant young scholar. Her brother will inherit Calrunaidi, and she has no shortage of prospects. She is sensible, good at figures, a credit to her parentage, which is Calrunaidi and Ardija. She is no beauty, but it is not beauty that recommends her.”

“Ardija,” Geigi said, nodding slowly. The aged lady of Ardija, as Bren well-remembered, was Drien, Ilisidi’s closest living relative in the East. It was a connection with her own estate of Malguri that Ilisidi proposed for Geigi.

“The young lady has rights there, but no inheritance: Drien of Ardija has a brother-of-the-same-mother whose son will inherit thatestate. So young Maie has better connections than she does prospects. She is a well-dispositioned child who could do far, far better than temporarily marry one of my neighbors and produce themheirs with her connectionsc frankly, a potential inconvenience to my house, which has no heir but this young gentleman, and heis too young for her.”

“Great-grandmother!” Cajeiri said in shock.

“Continue to be young,” Ilisidi said, brushing the matter aside. “Too young, I say, and the young lady is far too bookish for your taste. Not, however, for Lord Geigi’s interests, perhaps. Geigi may marry her.”

“ Marry,” Geigi said, still in shock, himself; and Barb and Toby were looking in Bren’s direction in some small concern, but it was no time to provide translations.

It was a brilliant piece of dynastic chess—if the individuals involved could be persuaded. The sticking point was persuading any young lady of taste to bed down with Baiji long enough. But thatmarriage could be contracted to last just as long as it took to produce an heir, then evaporate as if it had never been. The young woman would find herself quickly married to Lord Geigi, who might even visit the planet for the occasion—and thereafter, if one could read Ilisidi’s plans between the lines, young Maie of the East would occupy Kajiminda, deal with the Edi, and bring up a suitably educated heir for Geigi’s branch of Maschi clan. Maybe two heirs, if she and Geigi actually took to each otherc though the unspoken matter in the background was that Geigi was rumored to have very little interest in young ladies, and no success in getting an heir of his own.

“With adequate security for her residence here,” Geigi said quietly, “that above all. She would be an immediate target of our neighbors in the Marid. So would her child.”

“The Edi will be establishing their own house somewhere neighboring both Kajiminda and Najida,” the dowager said. “And one does not doubt they will become a force to be reckoned with.”

“But is that a certainty?” Geigi asked. “One believed it would still be under debate in the legislature.”

“Oh, pish,” Ilisidi said with a dismissive wave of her hand. “My grandson has a brain. He will agree with me, given the other circumstances. And he will see that the legislature agrees. The arrangement gives no great advantage to any single westernhouse, which would be the greatest sticking-point. So it will pass.”

It wasn’t going to be as easy as the dowager said, but with the possibility of a renewed set-to with the Marid looming in the immediate future, and another round of Marid-directed assassinations aimed at destabilizing the aishidi’tat, then counter-moves by the aiji, the house of lords might be inclined to give in and support the proposal. Even the hidebound traditionalists of the center, like Tatiseigi—who was a staunch ally of the aiji-dowager on other points—might be persuaded. One had the feeling of watching a landslide. Boulders were coming downhill, in the dowager’s planning, and damned little was going to stand in her way.

Certainly not one young bookish girl in—what was the clan? Calrunaidi. Nobody in the west had ever heardmuch of Calrunaidi.

But one had certainly heard of Ardija. That, tied closely to Malguri, and involving relatives of the aiji-dowager, was a bloodline of some potency.

And that alliance would tie the west coast firmly to Malguri, which was Cajeiri’sinheritance, until he produced an heir for it.

God. On the chessboard of politics, that was a potential earthquake. The great houses employed not only numbers experts, they employed genealogists to track this sort of thing. They would see it—but they likely would give way to it, in the interests of peace.

“One would agree,” Geigi said, “if this can be arranged.”

“Good, good,” Ilisidi said. “So you may think on it and tell me your thoughts when you have had time to mull it over. Perhaps we should have our last round and let you get to your bed, Geigi-ji. You must be exhausted.”

“One admits to it,” Geigi said. “And I shall indeed think on your proposal, ’Sidi-ji. I shall think on it very favorably.” He turned then to Toby and Barb, and said, in very passable ship-speak: “We discuss politics. Unavoidable. One wishes a more tranquil conversation.”

“An extravagant honor, nandi,” Toby said, one of his courtly phrases of Ragi. “One is gratified by your notice.”

He got it out without saying orange drink, a close thing, with the word notice. Bren was astonished.

But then—Toby had spent the last couple of years running messages between the Resistance and the Island, and his vocabulary hadn’t exactly rusted.

“You speak a fair amount of Ragi, nandi,” Geigi said.

“About boats, navigation, hello, and goodbye, nandi.”

“– se,” Bren tossed in, the felicitous false-one, since Toby had given a list of infelicitous four. It was natural as breathing.

“– se,” Toby added in the next breath. “We hear, but do not talk, nandi.”

Geigi laughed. “ Verywell done!” And continued, in ship-speak: “The station knows you as Frozen Dessert.”

Toby and Barb both laughed.

Frozen Dessert? Bren wondered.

“Our code name,” Toby said to Bren, “when the authorities had to refer to us.”

Bren translated that for the dowager, and for Cajeiri. “That was the word referring to them and their boat, during the Resistance, aiji-ma, young gentleman. When they were running messages.”

“And bravely done!” Geigi said. “The enemy would appear and the dessert would melt in the sun.”

“Little boat,” Toby said in Ragi. “Hard to spot.”

“Very good work,” Geigi said in ship-speak, and in Ragi: “Tell them that they will be welcome as my personal guests in Kajiminda, when I have done a little housecleaning.”

“He says you’re welcome as his guests at Kajiminda when he has things there under control,” Bren said, thinking the while that Geigi could not possibly follow through on that, and, please God, would never have to give up his station post to do so. But there was another round of polite sentiments, all the same.