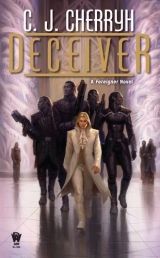

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Deceiver

C . J .Cherryh

Foreigner 11

To Jane.

DECEIVER

1

It was an interesting little pile, the stack of wax-stained vellum that occupied the right side of Bren Cameron’s desk, in his office, in Najida estate, on the west coast of the continent.

This stack of letters held treason. It held connivance. It held the intended fall of the whole coast.

It also held a set of interesting names.

Machigi of Taisigi clan was one of them.

Now therewas a piece of work. A younger man, quite young for a clan lord, in fact, he had inherited the ambitions of his predecessors down on the southern coast, but he had proved himself far, far more clever—and more dangerous.

A child named Tiajo was another name. A child of fifteen– and probably not as innocent of political ambitions as her tender age indicated. Machigi had intended to marry her off, a political wedge into the west coast—and as quickly make her a widow.

Once her husband was dead, of course, her relatives would step in to help run his estate—and that estate, a Maschi clan property, held treaty rights up and down the southeast coast of the continentc a district long coveted by Taisigi clan.

The third name, everywhere in those papers, was the addressee and source of those papers: Baiji of Maschi clan, nephew of Lord Geigi of Kajiminda. Baiji, who was the former lord of Kajiminda, betrothed of Tiajo—and the object of Machigi’s long-running plot.

Baiji, who happened, at the moment, to be locked in the basement under Bren Cameron’s feet, a prisoner stripped of all titles.

Najida, Bren’s estate, sat on a peninsula within Sarini Province, on the southwestern coast of the aishidi’tat, the nation-state that spanned the continent. Bren Cameron, paidhi-aiji, was interpreter and advisor to Tabini-aiji, who was ruler of the whole aishidi’tat. And in recent days, Bren himself had become the target of an assassination attempt directed from Taisigi clan.

Hence the sound of hammering, which was distantly audible. The staff was repairing damage to the garden portico from the latest of Machigi’s little venturesc and fortifying the house against the next.

Meanwhile, up on the space station, Lord Geigi himself, the lord of Kajiminda andof all of Sarini Province, had enough to do running atevi affairs on the station. He had not been pleased to hear the account of his nephew’s misdeeds.

Likewise Ilisidi, Tabini-aiji’s grandmother, the aiji-dowager, who had happened to be Bren-paidhi’s guest—along with her great-grandson Cajeiri, son of Tabini-aiji—had not been pleased with Baiji of Kajiminda orhis promised bride, no, not in the least.

And factor in the Edi, the aboriginal people of the island of Mospheira. The Edi, uprooted by the treaty that had given that island to humans, had settled on this coast of the continentc and had immediately become the enemies of Taisigi clan and their whole district, further south. The Edi, lacking a lord of their own, had been represented in the aishidi’tat by the lords of Kajiminda for the last two centuries, and the Edi were up in arms about their old enemies of Taisigi clan trying to move into that lordship.

Bren Cameron’s job as paidhi-aiji, interpreter, and mediator between Tabini-aiji and the two human powers—one on earth and one above the heavens—ordinarily included occasional peacemaking between atevi factions. But in this case, he was in the middle of the conflict, his erstwhile neighbor Baiji was the objectof the conflictc and Taisigi clan?

Taisigi clan was not in the least interested in peace or mediation. In the whole history of the aishidi’tat, the Taisigin Marid had never been interested in peacec never mind their recent overtures toward Tabini-aiji. Taisigi clan and its local association, the Marid, had claimed the southwestern coast of the continent two hundred years ago, when humans had landed on the earth. They had claimed it when the aishidi’tat itself had been forming. And, denied possession of that coast, and having the Edi moved in on that land, the Taisigi and their local association had tried to break up the aishidi’tat from inside. Then they had tried to overthrow it by seceding from it. Then they had rejoined the aishidi’tat, and most recently had tried to rule it by backing a coup in the capital—all these maneuvers without success. This last year, Tabini had come back to power in Shejidan on a surge of popular sentiment and driven the usurper out, hounding him from refuge to refuge while the Taisigin and the Marid as a whole had tried to look entirely innocent of the whole thing.

But neither had the aishidi’tat ever succeeded in bringing the Marid district under firm control. Lately, Tabini-aiji had even hesitated in kicking the Farai, another Marid clan, out of Bren-paidhi’s apartment in the capital. Oh, no, the Farai were all forTabini-aiji’s return: they had helped him; they were a strong voice down in the Marid, and they could be negotiated with. Of course the Marid had seen the light, and really wanted peacec so the Farai could not be tossed out of Bren-paidhi’s apartment. The apartment was theirs, after all, granted the aiji would only acknowledge they had inherited it via an obscure marriage with a fading clan fifty years agoc

It was, after all, all they wanted in return for their persuading the other clans of the Marid to make a lasting commitment to the aishidi’tat and finally put an end to all the rebellionsc

This stack of incriminating letters—which the double-dealing Baiji had, oh so slyly, preserved behind a panel of his office—told quite another story about the Farai and the whole Marid.

The letters represented the proposed marriage, involving a modest marriage portion of family antiquities that weren’t Baiji’s to dispose of—they were Lord Geigi’s—and the union of Baiji with young Tiajo and her family down in the Marid.

Fifteen. Old enough to be auctioned off, young enough that the question of an heir could be delayed a year or two. Long enough, one supposed, for the Marid to lay firm claim to the estate itself, by sheer firepower. Had the marriage actually happened, Tiajo’s southern clan, one of three major clans in the five-clan Marid association, would naturally have moved some of its servants in to attend the bride. Baiji would have been dead within a year of the bride producing an heir.

And immediately on Baiji’s untimely death, the grieving widow would have immediately laid claim to Kajiminda in the name of whatever offspring she had produced. She would get the backing of the entire Marid—and the Marid would finally gain that foothold on the southwest coast that they had been plotting so long to get.

Baiji hadn’t planned on that latter part—the part about him dying—but anybody of basic intelligence and any experience at all of atevi politics could see that one coming.

Anybody of common sense, too, could anticipate that, once in that position, and sitting in Kajiminda, young Tiajo’s family, in Dojisigi clan, would be nudging Machigi of the Taisigi for more power and importance within the Marid.

And of course the Dojisigi family members, backing Tiajo’s claim, would be sitting in Sarini Province, hiring Guild Assassins and creating their own power base on the west coast, in a bid to protect themselves within the Marid, as theirown greatest threat. They would go after Machigi.

Machigi, of course, smarter than that, would possibly assassinate his Dojisigi cousin in the Marid, possibly simply terrify him into peacec

And under the guise of an intra-associational dispute within the Marid, Machigi would take control of the Dojisigi, preparatory to setting his own relatives in command of the new Dojisigi holdings on the southwest coast.

Warfare, where it regarded the Marid, was endless. If it wasn’t directed outside, at the aishidi’tat, it was inside, clan against clan.

The aishidi’tat, under Tabini’s newly restored regime, was too busy reconstructing itself after surviving the lastattempt to kill it off. They would not want to involve themselves in an internal Marid quarrel, and they might think a Dojisigi-Taisigi power struggle would play itself out much more slowly, and give them time.

They didn’t havetime.

Young Baiji, not the brightest intellect on the west coast, had played for power of his own, and landed himself in very deep waters, which Baiji stillfailed to figure out. He didn’t, he protested, deserve being locked up, a prisoner, in the paidhi-aiji’s basement. He was innocent. He was misunderstood. He had been spying for the aiji all the while. He should be a hero to everyone. Of course he should.

Just ask him.

Baiji’s unfortunate machinations had put bullet holes in the hall outside this little office. They had caused the death of one of the aiji-dowager’s guard, the serious wounding of a young man from Najida village, and the complete ruin of the large front portico over at Kajiminda estatec not to mention the hole Bren’s own estate bus had plowed through the garage gate here at Najida, to the detriment of the adjacent garden.

Forgive Baiji? The paidhi-aiji was a generous and patient man. He was, more than anything else, a man for whom policy and the aiji’s welfare counted more than personal affront.

Baiji, however, had exceeded his tolerance in any reasonable consideration.

The quiet since the assault, about two days, had been welcome. Bren did not count on it lasting. Nor did his guest, the aiji-dowager.

They’d had the time, among first business, to recover this cache of papers from Lord Geigi’s estate at Kajiminda.

They’d had the time, too, to patch a largish hole in Toby Cameron’s boat—Bren’s brother Toby had been visiting here when all hell had broken loose, and Toby had been instrumental in thwarting the Marid in a secondary attack.

So, down at the harbor at the foot of the estate, the Brighter Dayswas now calmly at anchor beside Bren’s own Jaishan. Toby and Toby’s companion, Barb, were living aboard, not that it was safer down there on the boat, but that Najida estate was running out of room in the house. It was dangerous for Toby and Barb to be down there, exposed to view whenever they went out on deck. But it was more dangerous, potentially, to put out to sea and try to head home across the straits, in the event some southern ship was lurking offshore.

It was dangerous for them to come and go up to the house for meals. But Toby and Barb had stubbornly elected to take that risk, since the perimeter seemed secure and the walk up the winding slope from the dock was now safe from snipers—so they argued.

Toby’s presence on the continent, however, posed a risk in all senses, including political sensitivity, and Bren earnestly wished he could find one single twenty-four-hour window in which Toby could safely make a run home to Port Jackson, back to the human-run island of Mospheira, where there weren’tmembers of the Assassins’ Guild laying plans.

The grounds were under close and constant surveillance by the dowager’s young men, at least, and the aiji’s navy was out there somewhere—exactly where was classified.The house had reinforcements, besides: local fishermen and hunters. Najida villagers, ethnic Edi, had opted to support their local lord and his estate with their own informal armed force against the unwelcome intruders from the Marid. Edi folk were no strangers to violence or guerilla action, and their help was certainly not inconsiderable.

Add to that, the aiji’s forces, Assassins’ Guild from the capital at Shejidan, who had taken possession of Kajiminda grounds in support of Lord Geigi. Opposition forces had melted away from that threat—and the aiji’s forces, not to mention the Edi irregulars, were busy trying to ferret at least a dozen Marid agents out of Separti Township—having already run them out of Dalaigi. The infestation had moved, and was still dangerous—but at least it was on the run.

Further southc no word from that operation either. But one expected none.

Bren’s own bodyguard, of the Assassins’ Guild, had their own opinions of their situation, and refused to let him move about even inside the house without their being constantly aware of where he was and with whom. The aiji-dowager’s bodyguard, twenty members of that same Guild, counting Cenedi, who led them, was cooperating in house defense. And the aiji’s eight-year-old son, Cajeiri, had just acquired two young members of that Guild to back up the two Taibeni youngsters who were his bodyguards-in-training. That was twenty-six Guild personnel under the same roof, a tough objective for their enemies. They were on round-the-clock high alert, and thus far the Taisigi hadn’tmade another try.

Servant staff, too, were encouraged to stay on the estate grounds and not to go up and down the road to Najida village; and Najida fishermen were asked to stay away from the estate perimeters. The less traffic that moved on Najida estate perimeters, the easier it was to track anyone who didn’t belong there.

They were all wired for the slightest hint of trouble. Expecting it.

And a slight rap at the door drew Bren’s instant sharp attention.

Household staff never waited for an acknowledgement when they knocked. Neither did his bodyguard. And indeed, the door immediately opened. It was Banichi himselfc a looming shadow in the black uniform of his Guild. Ebon-skinned, golden-eyed, and a head and shoulders taller than a tall human, Banichi fairly well filled even an atevi-scale doorway.

And when Banichi ran errands, it wasn’t about tea or the delivery of mail.

“Bren-ji.” They were on intimate terms, he and all his bodyguard: he preferred it that way. “Tabini-aiji is approaching the front door.”

“The aiji.” Bren shoved back from the desk, appalled. Tabini was supposedto be safe in the capital. And he was here? On the decidedly unsafe west coast? Unannounced?

Bren got up and immediately took account of his coat—it was a simple beige and blue brocade for office work on a quiet day. The shirt cuffs—a modest amount of lace—he had carefully kept out of the ink in his writing a few notes. His fingers, however—

But it was late to make any improvement. Tabini didn’t stand waiting for anybody, and safety dictated Tabini should move fast if he was moving about the region.

In very fact, Bren heard the outer door open in the instant of thinking that. Banichi turned to check, took his station at the open door, and in a moment more, his partner Jago arrived and took her place: bookends, on one side of the office door and the other, while a heavy tread in the hallway heralded a second, armed advent through that open door.

The aiji’s senior bodyguard, two grim-faced men in Guild black, arrived and took theirpositions, automatic rifles in clear evidence.

Then Tabini-aiji himself, aiji of the aishidi’tat, lord of all the world except the human enclave, walked into the office. Black and red constituted the Ragi colors, the clan to which Tabini belongedc but Tabini wore no red today: Tabini blended with his black-clad bodyguard, right down to black lace cuffs. It was a mode of camouflage Tabini had used occasionally even in the halls of the Bujavid, since his return to the aijinate. He had used it habitually in that uneasy year he had spent on the run, and narrowly avoiding assassination.

A blond, pale-skinned human in a pale beige coat stood in quiet, domestic contrast to that dark and warlike company. His little office was now entirely overwhelmed with Guildsmen, all armed with automatic weapons, on alert and on business– not to mention Tabini’s own forceful presence.

Bren made a modest bow. “Aiji-ma.”

“Nand’ paidhi.” Tabini’s tone was pleasant enough. “One rejoices to find you in good health, considering your recent trouble.”

“Well, indeed, aiji-ma. And your great-grandmother and your son are both well under my roof, one is very glad to say.”

“The paidhi graciously accepted my son as his guest for– was it some seven days?”

A second bow, deeper. Numerical imprecision with any ateva was implicit irony. “Aiji-ma, one can only apologize for the succession of events.” A near-drowning and an assassination attempt were not the degree of care the aiji had a right to expect for his son on a holiday visit. “One has no excuse.”

“My wayward son is only one of my concerns in this district.”

He was remiss in his hospitality. He was utterly remiss. The aiji had arrived with the force of a thunderstorm, with considerable display of armed force, and the suddenness and implied violence had thrown his mind entirely off pace. Household staff would not be far from the door—hovering near, but too fearful to come in to the crowded office.

“Might one offer a modest tea, aiji-ma?” A round of tea was the ordinary course of any civil visit, even a visit on serious business. Tea first, and a space for quiet reflection for both parties, even in advance of knowing the reason of the call. “We could adjourn to the sitting room, should the aiji wishc”

“Doubtless my grandmother will drown us in tea in a moment,” Tabini said, still standing, arms folded, amid his guard. “The paidhi, however, can be relied upon to tell me the truth without an agenda, so my first visit is to you. What should we know?”

The paidhi indeed knew what was going on in the district. And the paidhi’s heartbeat picked up. It was a wonder the aiji couldn’t hear it from across the room.

Tell the aiji his grandmother had just promised the Edi, a hitherto warlike ethnic group, a province and a seat of their own in the legislature?

Tell the aiji his grandmother had happened to involve the aiji’s son and heir in her promises to the Edi, as a reaction to the Marid foray into Sarini Provincec the Edi being the Marid’s ancestral enemies?

“Aiji-ma.” He could personally use a cup of tea. Anything, for a social ritual and barrier. But he had no such delay, had nothing to occupy his hands and no recourse but complete honesty. “Regarding the involvement of the Marid in the neighborhoodc the aiji surely already knows that matter.” The aiji had a large intelligence network to tell him that. “The matter of the meeting at Najida, howeverc” He drew a breath. “The aiji knows that the Edi clan staff had withdrawn its services from Kajiminda. This was in displeasure at young Baiji’s dealings with the South. The proposed marriage—”

“We are aware. Continue.”

“An Edi representative approached Najida covertly, advising me as their neighbor, and advising your great-grandmother as a person of revered presence, that the Edi clan was active on the aiji’s behalf during the recent Troubles. The Edi claim to have kept the usurper’s regime from controlling this coast. They claim to have continued this action, allied with the Gan people in the North, in the face of Kajiminda’s flirtation with the South. They say that the network that protected the coast from Southern occupation during the Troubles still persists. The group that has made contact with me and with the aiji-dowagerc”

“Who has promised them a province and a lordship! Is this astonishing news true, paidhi?”

He bowed his head. “True, aiji-ma.”

“With the attendance of my minor son at the meeting!”

“That is true, aiji-ma.”

Tabini glowered. It was not pleasant to be the center of that contemplation.

“Why, paidhi, did this seem to anyone a good idea?”

“One finds oneself, officially, in a difficult position with the Edi, aiji-ma. Overmuch discussion on this matter might compromise the paidhi’s usefulness to the aiji in negotiations, but it does seem to the paidhi-aiji that there may be advantage in considering this proposal. If one may explain—”

“We appreciate the delicacy. Continue in plain words, paidhi-aiji! And limit them!”

“The Edi’s reluctance to deal with the aiji’s clan persists. That has not changed. But they are finding themselves constrained by events. They claim that they supported your regime during the Troubles and will be willing to do so now—their old enemies the Marid having backed the other side. This offer has a certain urgency, in light of the Marid move against Kajiminda.”

“Ha!”

“Additionally—” His allegiance should be to Tabini, wholly, unequivocally. An ateva would have trouble feeling any other thing. A human—a human was hardwired for ambivalent loyalties. It made a human particularly good at the job he did for Tabini.

But it made relationships a little chancier, and led, sometimes, to dangerous misunderstandings.

“One hopes the aiji will not doubt my man’chi to the aijinate and to him, personally. But the Edi request my good offices in negotiation—and they request me, as their neighbor, to maintain a certain discretion regarding their actionsc a request with which I sense no conflict with my man’chi, aiji-ma, in regard to any—past event.”

“Be careful, paidhi. Not everyone in the aishidi’tat understands your motives. And one doubts that the Edi fully appreciate the workings of your human mind.”

A bow. “One is keenly aware, aiji-ma, that one is neither Edi nor Ragi. One suspects this approach on their part represents a test of some sort.”

“A test, and not a maneuver for advantage?”

It was a good question. A dangerous question, worth considering. And he had. “One rather perceives it is a test, aiji-ma. And in my perception, such as it is, their secrecy in asking this meeting has in no wise involved ill intent toward the aiji or his representatives—rather a desire of the Edi to continue their actions under their own direction.”

“Ha! No different than they have ever demanded!”

“But these are not the foundational days, aiji-ma. These have been troubled times up and down the coast. And the Edi have behaved civilly. Thus far—thus far, they have preserved this estate during the Troubles, and kept my staff safec”

“Because their worst enemies are on the other side.” Tabini unfolded his arms and took two vigorous steps to the side before looking at him askance. “One takes it you have already—under the aiji-dowager’s encouragement—agreed to this arrangement?”

Bluntly put. Bren bit his lip. “Initially, and on the paidhi’s best judgement, aiji-ma, yes.” A deep breath. “The confidences they have given me thus far are reasonably minor, which is why I say it is a test of confidentiality. Should these confidences ever involve questionable activities—” Smuggling was only one of the local industries. Piracy was another. “Should there be criminal action—one would still feel constrained to maintain a certain discretion on their behalf, to keep the compact alive, and to keep channels of communication open, for the aiji’s ultimate benefit. The point is, one cannot be totally forthcoming to you, aiji-ma, and simultaneously maintain their confidence in me. They wish me to step aside somewhat from my attachment to the aiji: evidently they wish me to mediate on their behalf.”

A snort, an outright snort. “Ha! So theywant the human! Therein lies their isolation from the mainland! Theywere the ones to come too close to your people on the island, paidhi-aiji, not we! If you look for the causes of the War of the Landing, look to the Edi, who thought they could live in two houses at once.”

“We say—sit on the fence, aiji-ma. Having a foot in either of two territories.”

“Descriptive.”

“Humans do truly understand this behavior, aiji-ma. But my two-mindedness is a capacity that has served you. Whether the aiji chooses to grant me latitude in this case—will dictate how useful the paidhi may be as a negotiator in this matter.”

“That latitude has operated profitably in the past.”

When he had represented the human government on Mospheira. For the last number of years he had represented the aiji in Shejidan with a closeness that had moved further and further from representing his own species. Perhaps some atevi had begun to think he had profoundly changed in that regard. But, on the other hand, some still suspected his motives as secretly pro-human.

“It may not improve my acceptance among Ragi, aiji-ma, but yes, it could be profitable for me to do so. And my man’chi to you will not vary. It will not.”

“Granted, granted,” Tabini said. Which was what had made Tabini rare among atevi—an ateva willing to use a little blind faith, with adequate safeguards. “Provided you take no chances with your own safety. We are not willing to lose the paidhi-aiji. Especially to the Marid!”

Appalling thought. “One will certainly take adequate precautions.”

“You are understaffed here. Woefully understaffed.”

“Aiji-ma—one is compelled to rely on Edi clan irregulars for more extended security. And this does make me uneasy, since it is a security which involves the safety of the aiji-dowager and of your son, aiji-ma, for which I feel personally responsible. But one sees no choice. One cannot make this house or Kajiminda—in their eyes—a Ragi base of operations—or we lose a valuable ally, andthe hope of alliance.”

“Hence your failure to appeal for reinforcement.”

Embarrassing. He bowed. “Yes, aiji-ma.”

“Never mind my grandmother’s obstinacy in the case. Have these Edi the force and the organization to protect this whole district?”

“One doubts they could adequately do that, aiji-ma.” He saw what Tabini was aiming at. “They have been effective in holding this peninsula. One believes this is the territory they will insist on holding. Your forces, I understand, have Kajiminda Peninsula secure.”

A snort. Another brisk stride. Two. “As secure as a wooded peninsula can be. You know you are making yourself a target, paidhi. And a target of more than Southern ambitions. The central clans will hear that the paidhi-aiji has abandoned neutrality in this matter: that he has affiliated with a specific district, specifically one they have never favored.”

“One is aware, aiji-ma, that there may be that future difficulty.”

“More than a small difficulty. And not far in the future.” A pause, and a direct, calculating look. “One wouldsurmise you want the Farai out of your apartment.”

The Farai had camped in his capital apartment since the coup, and persisted there after Tabini’s return from exile: during the Marid’s new approach to dealing with the aiji’s authority, they had been politically difficult to toss out on their ear. Which was whythe paidhi had come to his west coast estate for a quiet retreat.

At which point the Marid, finding him lodged next door to their plot at Kajiminda, had promptly attempted to assassinate him.

Which was, of course, whyhe had the erstwhile lord of Kajiminda locked in his basement.

“My greatest concern in the capital, aiji-ma, would be yoursecurity. The return of my apartment would be a great favor to me, yes. But the Marid is up to something, I have partially exposed it, and the Farai are lodged next to yourapartment wall: thatsituation more concerns me. This whole scheme is aimed at their gaining the coast and reopening the war. Thatmakes the Farai a hazard where they are.”

A grunt. A wave of the hand. “Explaining this construction of conspiracies will take preparation. One will make known the paidhi’s displeasure with the South, and his current personal grievance against the Marid. That will explain certain of the paidhi’s moves to public opinion.”

It would go a certain way toward justifying his actions, in public opinion. If the South had attempted to assassinate the paidhi, and that event became public knowledge, the paidhi’s moves against Southern ventures on the west coast achieved complete justification in the atevi way of looking at thingsc and not just for a quarrel regarding a Bujavid apartment. It was a great favor, and politically astute, that the aiji should put that information out through the aiji’s own channels.

“One is very grateful, aiji-ma.” He was, in fact. It lessened very major difficulties. It didn’t solve them, not with the most determined of his detractors. It would, however, make reasonable people think better of him. “But I remain concerned about your grandmother and your son being in this situation with me. The aiji-dowager has been helpful, even instrumental in starting this negotiation, but if you could persuade her—”

“An earthquake could not budge my grandmother,” Tabini said with a wave of his hand. “I shall at least talk to her. Where is she?”

“One believes, in her rooms, aiji-ma.” A bow, a gesture toward the door. One did not dismiss the aiji of the aishidi’tat to a household servant’s guidance. A lord escorted him where he wished to go, and relied on the bodyguards—his, and Tabini’s, to quietly exchange information in the background. If the dowager were notin her rooms, his staff would quietly redirect themc but crowded as the house had become, it was certainly a small range of possibilities, and they were already inthe office.

It was a short walk, out into the wood-paneled hall, with the stained-glass window at the end, darkened now by storm-shielding, down that direction to a paneled door. Banichi’s single rap drew immediate attention from within. The door opened, Cenedi himself doing that office from inside. The aiji strode ahead into the dowager’s personal sitting room with a loud, “Grandmother?”

Ilisidi was sitting in a comfortable wing chair by the fireplace, a notebook in her lap, the picture of anyone’s kindly grandmother. Her hair was liberally salted with white, her dark face was a map of years, and she was diminutive for her kind, only human-sized. But the golden eyes had lost none of their spark and snap, and she was dressed in a brocade day-coat the collar of which sparkled with diamondsc the hell she hadn’t gotten wind of this visit.

And considering the force of the two personalities about to engage, the paidhi-aiji decided it was time for a tactical retreat. Bren began to back toward the door.

“Stay, paidhi!” the dowager snapped. “You may be useful.”

He stopped. “Aiji-ma,” he murmured and, beside Banichi, Jago, the aiji’s guard, and Cenedi, the chief of Ilisidi’s guard, he took a place along the wall, beside a tall porcelain figurine of the recent century.

Tabini-aiji; meanwhile, settled for a casual stance by the fireplace, in which only a trace of fire burned above the embers. “Well,” he said, elbow on the mantel, “honored grandmother. A new province? Or is it two? War with the Marid? When shall we declare it? Do tell me.”