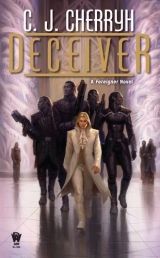

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Anger does not plan. When one Files with the Guild, one does not File Anger. One Files Intent, because one has thought clearly and seen a course of action. The Guild officers meet and decide to accept or not accept the Filing, and they will not accept it if the outcome destabilizes the aishidi’tat. That is their rule. It takes far more than anger to direct the aishidi’tat, boy. So do not sulk at me. Think! If you are a fool, your Filing will never be accepted. Your enemy’s may be more sensible. Think about that, too.

He had objected, But I shall be aiji, and they have to accept it!

They do not!mani had said. Fool!And his ear had been sore for days after he had said something that stupid.

So was nand’ Geigi on the phone Filing on the Maschi lord? Surely the Guild would notaccept the Maschi lord Filing on nand’ Geigi, even in self-defense. That would destabilize the whole heavens.

So the Maschi lord was really stupid for annoying Lord Geigi.

And was the Guild leadership meeting at this hour, and voting about that? Or was nand’ Geigi actually going to go to the Maschi holdings to make Lord Pairuti make a mistake and get a clear cause for Filing? Did he need to do that?

There were so many questions he wanted to ask someone. The world was a more dangerous place than the ship, that was sure.

But getting underfoot of his elders when serious things were underway was a way to get another sore ear, or worse, to be shipped back to his father in Shejidan—and that would mean dealing with his tutor, who would have a stack of lessons, not to mention Great-uncle Tatiseigi, who had moved in down the hall.

That was just gruesome—besides having mani and nand’ Bren in danger and not being able to know anything at all that was going on.

So he stayed good.

Mostly.

And fairly invisible.

He was not a follower, that was one thing; he was not designed to sit and wait. He would be aiji someday, and people would have to follow him, and that was the way he was born: mani said so.

And when he was aiji and the world was peaceful again he would go fishing when he wanted to and have his own boat.

Except his father never got to go fishing.

That was a grim thought.

He saw no way to change that. He wanted not to be shut in the way his father was.

But day by day he could feel atevi thoughts taking hold of him.

You will know, Great-grandmother had told him when they were about to come down from the station. When you are only with atevi, you will know things that will make sense to you in ways nobody can explain to you right now.

He had doubted it. But he did, that was the scary thing. When he thought of all of it, he got really madc so mad he wanted to go fight Machigi, who was at the center of all this. Mad at Lucasi and Veijico for being so snotty and notbeing impressed by him.

Which was what he was supposed to feel, he supposed. It was what everybody expected of him. But in a way, it made him sad and upset.

Because he had much rather be out on the boat fishing, and not feel like that at all.

“Go back,” he told Antaro, “and keep listening. I want to know everything going on.”

15

« ^ »

It was the small hours, and with the house overburdened with guests and packing for what could either be a civilized argument or a small war prefacing a bigger one, there was, in a hot bath, one quiet refuge for the lord of the house. A folded, sodden towel on the marble tub rim became a pillow. Bren drowsed, was quite asleep, in fact—and wakened to a gentle slop of water and the awareness he was no longer alone in the ample pool.

He wiped his eyes with a soggy hand, and ran it through his hair. “How are things going, Jago-ji?”

Jago sighed, arrayed her arms along the tub rim, and tilted her head back, eyes shut. “One is satisfied, Bren-ji. Your cases are packed. As are ours. The bus is loaded. Tano and Algini have just come in, with Lord Geigi’s bodyguard. And we now have eight of the aiji-dowager’s own guard going with us.”

Eight. That was a considerable deployment of that elite company. But a worrisome one—depleting the dowager’s protection. The Edi might be an adequate backup over at Kajiminda, which had no attractive targets, but not at Najida, where the aiji-dowager andthe aiji’s heir were situated. “One is astonished,” he said moderately, “and honored. But what about provision for the aiji-dowager’s force?”

“Discreetly placed. They are here about the house, Bren-ji, is all we should say. Even here.”

He drew a deep breath. He had run on too little sleep. The cavernous bath seemed to echo with their voices. Or they were ringing in his head.

He had a dread of this venture upcomingc this venture specifically designed to provoke an attack from somebody– and they weren’t sure who.

He wished he had any other team to throw into it besides Banichi and Jago, besides Tano and Algini. He didn’t want to risk their lives this way—all for a pack of damned conniving scoundrels, and a clan too weak to say no to bad neighbors, too self-interested to have seen what kind of a game they were playing. He seriously considered, truly considered for the first time, Filing Intent himself and seeing if political influence could speed the motion through the Guild without it hanging up on regional politics.

But the paidhi didn’tFile Intent: that was the point of his office—he was neutral. He hadno political vantage.

Until Tabini made him a district lord. Dammit.

Geigi didn’t want to File on his own clan lord—even if he outranked his clan lord in the aishidi’tat. It was a point of honor, a sticky point, the long-held fiction of Geigi’s being insidethat clan. Bringing that fiction down would rebound onto clan honor—or make Tabini haveto inquire, officially. And the plain point was—when there was a quarrel insidea clan, things were supposed to be settled, however bloodily, without recourse to the Assassins’ Guild, except those already serving within the house.

So they were going in, with Geigi’s aishid running the operation. They were going to geta provocation, or get a resignation, or get a direct appeal from Lord Pairuti for Geigi’s support against the neighborsc and the matter was so damned tangled it was hard to predict from here just what they’d get from the man.

Things echoed back surreally. He had a feeling of being momentarily out of body, looking down on him and Jago, at a point of decision that he could critique, from that mental distance. From here, he knew how dangerous their situation was, and how they could make mistakes that would cost their lives, cost the aiji the stability of the aishidi’tat, and leave the whole atevi civilization vulnerable. Civil war was the least of the bad outcomes that could flow from the decisions he was making—on too little sleep, too little information, and with deniability on the part of Tabini-aiji. Cenedi had talked about calling in certain forces under his own command: but Cenedi’s focus was, when all was said and done, the dowager, and the heir.

The most important thing right now was Tabini’s survival, Tabini’s power. There was, God forbid, even a second heir. Or would be. The aishidi’tat would survive losing anybody– the out-of-body detachment let him think that unthinkable thought– anybodyexcept Tabini, because in this generation there was no leader butTabini that could hold the aishidi’tat together.

So Tabini had to survive.

All the rest of them were expendable, on that terrible scale. He was exhausted. His mind was spinning into dire territory. He was scared, but he was so far down that path he didn’t see an alternative.

Maybe it was a failure of vision. Maybe he should go to the phone, shove it all off on Tabini and let him deal with it. But he couldn’t see that ending productively. And Geigi couldn’t go in alone. Geigi was willing to do it, but hellif they could afford to wave that target past the attention of their enemies.

So there they were. They had to go in, hoping to frighten Pairuti into cooperating.

He leaned his head back on the towel-cushioned rim and shut his eyes, wondering if his mind and Jago’s were on the same grim track. The water was going a little cold. He moved finally, reached, and turned on the hot water. The current flowed in, palpably warm.

“Has one been a fool, Jago-ji, to get into this situation?”

“Not a fool,” Jago said. “Banichi does not think so.”

“Do you?”

“No, Bren-ji. One would not think so—even if it were proper to think. This is overdue.”

“On this coast?”

“In the whole quarter of the aishidi’tat—this is overdue.”

“What is the Guild’s temperature? Can you say?”

“Favorable, in this,” Jago said. He had half expected she wouldn’t answer. But she did. And he felt better.

“I have ceded our bed to Lord Geigi,” he said apologetically. Jago had gotten no more sleep than he had—less, if one counted falling asleep in the bathtub. “But this is comfortable.”

“I have located a place,” Jago said. “A solitary place. In the servants’ wing.”

That was clearly a proposition. A decided proposition. He smiled wearily and decided maybe—maybe both of them could benefit from distraction.

So he shut down the hot water and looked for his bathrobe.

16

« ^ »

The bus was loaded with luggage and gear. It waited under the portico, sleek and modern, pristine except the track of bullet holes across its windshield. Lord Geigi’s four bodyguards had caught a little sleep before breakfast—and Cook had scrambled to feed them handsomely, not to mention the rest of the household. The Lord of Najida and his guest would not go off unfed.

And, after breakfast, there were calls to make: on Toby, to be sure he was well. Cajeiri, poor lad, had argued to have his breakfast at his appointed post, and now was fast asleep in his chair, his bodyguard tiptoeing about to avoid waking him or Toby.

For Toby he left a note—in Ragi, in care of Antaro, for Cajeiri to read, since Mospheiran script was not one of Cajeiri’s many skills. It said: Brother, Ragi cannot truly express all the sentiments I have this morning. Please take care and follow instructions. We believe that the move we are making will turn up information on Barb’s whereabouts and lead to finding her, though it may not be simple. We are sparing no effort and we expect eventual success. Think of me as I shall be thinking of you.

He had a last look, in case Toby should have waked—he had not—and left quietly.

Last—a call on the aiji-dowager and Cenedi.

He walked alone into the dowager’s sitting room, where the dowager was having an after-breakfast cup of tea, and bowed very deeply.

“Aiji-ma,” he said, and received, uncharacteristically, a gesture to approach closely. He did so, and knelt down at the side of Ilisidi’s chair as if he were a second grandson. Cenedi stood up, by the mantel.

“This is very vexing, paidhi-ji,” Ilisidi said. “Cenedi argues against my going with you and unfortunately his reason prevails, since that equally unreasonable great-grandson of mine will be entirely on his own if we both should go on this venture.”

“I am only sorry to have been selfish, aiji-ma, in refusing to lend you Tano and Algini, but should one truly need them—”

A flick of the hand. “Pish. You are being sensible. Cenedi is the one being unreasonable, are you not, Cenedi-ji? He worries too much.”

“Always, in your service, aiji-ma.”

“One begs,” Bren said, “that you will listen to Cenedi-nadi and take very great care. I leave my household and my trusted staff in your hands, hoping they may be of service. Your great-grandson has been in constant attendance on my brother. Both were asleep when I looked into the room, and one hopes you approve the young gentleman’s absence. He has been very good.”

Ilisidi arched a brow. “Your brother will be in our care, nand’ paidhi, under all circumstances. Have confidence in that.”

“One is extremely grateful.” He bowed, hearing the implication of dismissal in that tone, and knowing he was delaying a busload of people. He bowed again, and with a little nod to Cenedi, took his course out the door and down the hall to the door, where Ramaso stood in official attendance.

Supani and Koharu were there, too, his valets, who bowed, and followed him to the bus. He had asked Ramaso, quietly, whether someone from the Najida domestic staff might volunteer for what might be a dangerous venture—servants were always exempt from assassination, but finding their way home could be lengthy and difficult; and shots strayed. It was, however, a great advantage for him and Geigi to have their own staff with them, those who would be closest and most intimate—an extra set of eyes and ears.

For himself, he had one intimate secret, as he boarded the bus, a very uncomfortable waistcoat he had just as soon not wear for several hours at a timec but that was the rule of the day. His staff had gone to great effort to put that item together out of one of Jago’s very expensive jackets, and out of spares from several of the staff, in Geigi’s case. The vest was heavy and it was hot; but the household had labored hard in that cause, and, in point of fact, produced two brocade vests, differently styled, that were more than they seemed. Others might think the paidhi, like Geigi, had been enjoying too many of Cook’s excellent desserts—but Maschi clan had never met the paidhi-aiji, which was to the good in this instance, and they had not seen Geigi in years. Well-tailored coats had had to be let out, in Geigi’s case—Geigi had laughed and said his seams were always generous. And staff and folk from the village had outright madethree new coats for the paidhi-aiji to accommodate the protection.

He nodded to his own staff; to Tano, and Algini, Banichi, and Jago, and sat down with them on the bus. Geigi had settled with his bodyguard around him, and his senior two servants. That was the sum of twelve, counting Kohari and Supani; fourteen, counting a brave volunteer from Cook’s staff, who was going to handle all food and drink for them; fifteen; and eight from the dowager’s guard—twenty-three; with gear and baggage jammed under every seat in the bus and into the luggage area below. The bus was all but full—and then the door opened again and five more persons Bren did not know showed up—not the dowager’s, not his, not Geigi’s, but they wore Guild black, and Cenedi personally shepherded them aboard.

“Who are they?” he asked Banichi, who would be in contact with Cenedi, and Banichi said, simply, “Backup.”

It was very, very likely they had just arrived from overland or from the airport: Tabini’s, unofficially, he suspected, and did not ask. The five reached the back of the bus, some to ride standing, and staff somehow jammed more baggage into the underside of the bus.

The engine started.

They were a packed bus, they were probably full of ammunition and heavy as sin; and with Tano and Algini aboard, they undoubtedly had electronics and explosives stowed somewhere. He tried not to think overmuch about that—and remembered he could have ordered bulletproofing, and had settled on speed and fuel efficiency.

He drew in a large breath against the stiff vest and let it go, trying to settle his nerves.

Ramaso stepped briefly onto the bottom step of the bus to look inside and make eye contact with Bren, in the case there should be last-moment instruction. Bren just lifted his hand, a signal that he needed nothing, and Ramaso stepped back down again.

The driver shut the bus door and put them into gear, rolling gently over the cobbled drive and ponderously and slowly up toward the road. Fans cut on, a relief, just to have air movement.

“One might get a little sleep,” Banichi said, “since it was scant last night. You in particular might, Bren-ji.”

Geigi had settled deeper into his seat, folded his arms across his armored middle, and seemed intent on dozing.

Bren was not relaxed. His mind was racing in a dozen directions at once, whether they would meet trouble on the way, whether they were going to meet shut doors and problems at the outset of their visit to Lord Pairuti, or whether they would be welcomed inside. He had far, far rather have relations all blow up on the doorstepc except that one of their goals was information on Barb’s whereabouts, and another was getting Pairuti to spill what else he knew.

So shooting their way in was not in the plan—unless they had to.

So, so much better if Pairuti would melt on their arrival on his doorstep, appeal for rescue and accept Geigi’s intervention– after which they could remove any agents the Marid might have gotten onto Pairuti’s staff, find out what they needed to, and hopefully negotiate something that would get Barb out of Marid hands, get the Farai out of his own city apartment, take Machigi of the Taisigi down a peg or two, and settle a few years of relative calm and peace.

Then they could dust off Pairuti’s authority and set him back in power again with Tabini’s blessing, so Geigi could get back to the station and get back to his real work—which would be the best outcome for everybody but Machigi.

There were a lot of ifs in their plan. They were, somewhere in the plan, making Tabini unofficially aware what they were doingc which was whythey had those several strangers in the back of the bus, he supposed. Tabini’s men, no question, though his own aishid had not explained their presence. Since they had notexplained, he was apparently not encouraged to ask too much about them.

They couldeven be high-up Guild, along for their own reasons. When the Assassins’ Guild sent its own agents into a situation, it was usually in the interests of keeping the lid on aftershocks and making sure no Guild members got ordered into some lord’s suicidal resistence to the aiji’s orders. He’d never seen it happen—possibly because Algini had served in that capacity, once upon a time.

And, Algini having resigned that covert capacity in favor of closer attachment to the paidhi-aiji, it waspossible the Guild had sent observers to identify persons that might be on the Guild’s own wanted list.

Most of the outlaw Guildsmen from up north were clustered around Machigi, as best he could figure, but it was possible they’d be running up against a few, considering Targai lay close to the Marid. Again, his bodyguard hadn’t been too forthcoming about that aspect of the operation. Guild justice was strictlya Guild matter and the paidhi-aiji was not informed at that level. Nor was Geigi.

The bus took the turn to the Najida-Kajiminda road. They would go past the Kajiminda turnoff and then onto what became the Separti market road, before they turned off toward Maschi territory.

Their Cook came up the aisle to ask, Would one like tea, or anything stronger? One was tempted, but—

“No, nadi-ji,” he said, and looked across to Lord Geigi, who had waked. “Anything my guest or his staff wishes,” Bren said, “my staff would delight to supply.”

“The situation regarding my clan has quite depressed my appetite,” Lord Geigi said. “Such elegant transport to such an unpleasant event. One is astonished by the comfort. And perhaps we could do with tea.”

“Certainly,” Bren said, and ordered it.

“One is grateful,” Geigi said, across the aisle. “One is very grateful, Bren-ji. How far we have come, have we not, from the days we first met? Let us hope this goes smoothly. It only needs common sense.”

“One concurs,” Bren said. “One hopeshe is under pressure that we can relieve. And if Barb-daja should be held there—”

“Baji-naji,” Geigi said to that hope. “One is far from certain of his motives for paying social calls on my nephew, but in company with Marid agents? Introducing them?” Geigi heaved a massive sigh. “My clan has generated two fools and they have simultaneously gotten in power.”

“In your nephew’s case—not without Marid help. Perhaps we can relieve Pairuti of that problem.”

“Well, well,” Geigi said, “let us have a little tea and cease worry. The outcome of this now is my cousin’s decision, not ours.”

It was familiar scenery, down to Kajiminda. The road thereafter—Bren remembered from his earliest venture onto the west coast—cut through a small woods, and then a rolling stairstep of small hills and grassland that led on down to the coastal township of Separti, the larger of the two towns in Sarini province.

But at the divergence of the Maschi road, the track went off toward the east, through territory Geigi might remember, but Bren assuredly had never seen. The land gradually rose, became a meadow studded with large upthrusts of gold rock, and finally sheets and tables of stone where the road crossed a small river gorge that Geigi said was the Soac much less impressive a river than it appeared on a map, but an excellent view of weathered stone that tourists might admire.

A man planning unhappy actions in the adjacent territory, however, looked on it as a chokepoint in any escape plan, one worth remembering, and Bren was sure their respective bodyguards took note of it.

Beyond the gorge, the road gently climbed again, to a high plateau, and wide grasslands and scattered woods.

“This is Mu’idinu,” Geigi said. “My clan homeland.”

If one had had no prior knowledge of the Maschi, then, one would still have understood a great deal about them, seeing that great grassy plain, with a handful of tracks branching off the main road that were more footpaths than real roads.

This clan hunted. From coast to coast of the aishidi’tat, there were no domestic herds, such as humans had had in their lost homeworld. There was no great meat distribution industry, though such had begun to appear, since airliners had made the impossible possible. An atevi district, aside from that—and traditionalists greatly questioned the ethics of transporting meat—ate local game supplied by local hunters, in its appropriate season, and not a great deal of it. There was fish, mostly exempt from seasonality, even by the traditionalists; and there were eggs, which were a commercial operation; and there was wool, but no meat came from that operation. One simply did not eat domestic animals. Even non-traditionalist atevi were horrified at the notion.

A hunting clan, and vast, undeveloped lands: that said a great deal about the psychology of the clan. They would be nominally independent, but very dependent on their markets for things they lacked, manufactured goods, and the like. They had, despite a cadet branch of their house being on the coast, been historically isolated from their neighbors, except in trade at appointed locationsc one of which logically would always have been their common border with the Marid.

And their original good understanding with the coastal Edi had eroded over recent years—since Baiji had offended the Edi. That little detail had come clear in the various dry papers and accounts: mind-numbing detail, but the story was in them. Trade with the west had stopped and not resumed. The fish market had dried up. So if this district was not eating onlyseasonal game, it was getting its fish, that staple of various regional diets—from some other direction.

Like its eastern border.

The Marid.

Curious, the complexities that turned up out of such mundane information as the Najida market figures.

One began to form a theory on the Maschi’s actions during the Troubles: that the Maschi had become a target of Marid diplomacy, economically and politically—they had been tied to the central district and Shejidan during Tabini’s rule, but when Tabini had been out of power, and once Kajiminda fell into arrears on its accounts with Najida fisheries—

The Maschi clan estate at Targai had fallen right into the arms of the Marid.

Geigi had an unaccustomedly glum look as he gazed out on the broad plateau—remembering, it was sure; regretting, to a certain extent, the situation of his clan.

And Bren, looking out at that same landscape, thought about Barb, and a lot of personal history; and Toby, and his promise, and how the data that had made things seem possible back in Najida were having an increasingly spooky feeling in all this untracked grassland.

There had been no ransom demand from the kidnappers. That, he found ominous. That said they were traveling—further than some nearby hideout. Or that somebody was figuring out what to do with a human hostage.

And that question would likely go right up the chain to Machigi in the Taisigin Maridc guaranteeing at least some period of safety for Barb. Andc he could not but think it without much humor at allc Barb was as likely to make herself a serious problem to her kidnappers—which could mean she was not as well off as one would ordinarily hope. They would not likely hurt her—since it was unlikely they could figure out her rank or her right to pitch a fit; but she could push them too far. Knowing Barb, she would take a little latitude as encouragement to push. And that wouldn’t be good. Not at all. He’d personally had an arm broken—by an ateva who didn’t know how fragile humans were.

Not to mention food. God, they could poison her so easily without the least intention. Just one wrong spicec Stick to the bread, Barb, he thought desperately. Please stick to the bread.

The servant collected the teacups. Geigi sighed and seemed apt to drift off to sleep.

“Has there been any news?” Bren asked Jago quietly, not to disturb Geigi.

“None yet,” Jago said. “Guild to Guild, Lord Pairuti has been informed officially to expect visitors. They have not phoned the Marid. We know that.”

Thatwas interesting. His bodyguard, over the years, had increasingly taken to informing him on things lords often didn’t find outc things somewhat in the realm of Guild secrets.

“But then,” Tano said, “the Marid Guild has its own network.”

“Illegally so?”

“Oh, indeed illegally, Bren-ji,” Banichi said in his lowest voice. “But then, they are no longer privy to our codes.”

Tano said, from the facing seats: “The Guild has at least taken pains to keep them out. But we take care not to rely on that.”

“If there is any Marid Guild in this district,” Jago said, “they will not be minor operators. And they will not be taking orders from the Maschi.”

“The Maschi lord,” Tano said, “directs nothing regarding any Marid operation. If Barb-daja is there, she will not be in his hands.”

“Therefore she will not be there,” Bren said glumly, “and we may expect they will move her as rapidly as possible to the Marid, I fear too rapidly for us to overtake them.”

“Plausibly so,” Algini said. “The best we may hope for, nandi, is to settle the Maschi.”

“By reason or otherwise,” Tano added. “And one very much doubts reason.”

“Nandi.” Algini, who had had a finger to his ear, listening to something relayed to him, took on a very sober demeanor. “Go to the convenience.”

At the rear of the bus. It was not better shielded back there. It was not the potential for gunfire that Algini meant, not so, if he was to be leaving Geigi behind. It had to be informational, a consultation waiting for him back there.

He got up and quietly walked down the aisle to the vicinity of the several strangers who had boarded with them. Algini was right behind him, and so, he saw, turning, was the rest of his aishid.

Which had to alarm Geigi’s bodyguard. He cast a look back down the aisle and saw none of that lot stirring.

The next glance was for Algini, who said, in a low voice, “The aiji has Filed, Bren-ji. Word has just now come through.”

“Filed.”

“On Pairuti, on Machigi, on every lord of the Marid.”

“One believes,” Jago added dryly, “that the Farai will be quitting your apartment tonight.”

The strangers near them could hear, surely. So could the domestics sitting nearby, and several of the dowager’s guard.

“Lord Geigi—should not know this, nandiin-ji?”

“His bodyguard, nandi, is simultaneously receiving the same information,” Tano said.

Then a glimmering of the reason came through. But he was not sure. “But Lord Geigi—”

“His honor and his position,” Banichi said, “would require he advise Pairuti, Bren-ji. His bodyguard need not do so. They will not advise him.”

“One understands, then.” He almost wished hehad stayed ignorant. Far better, indeed, if Geigi were not put in a delicate position. His own, human, sense of honor was hard-put with the information—how to approach Pairuti with apparent clear conscience—how to walk into that hall and betray nothing. It was not fair play. It was not honest. It was not—

It was not easy for his aishid, either, to breach Guild secrecy and bring their lord in on the facts—on Tabini-aiji’s business. He had no good instinct for what had moved them to do so, except that, he, more than Geigi, was adjunct to Tabini-aiji. Hell. He needed to understand that point.

“Why have you told me, nadiin-ji?” he asked outright.

“Tabini-aiji has specified you may be advised, nandi,” Algini said. “But that Geigi should not be.”

Use his head, then. That was what Tabini expected of the paidhi-aiji. Function in his official capacity. Think his way through. Advise the Guild, for God’s sakec nobodyadvised the Guild, except he had Banichi and Jago in his aishid, who had been Tabini’s; and Algini, who had been the Guild’s; and God knew what Tano had been, or why he had come in attached to Algini. His brain raced, finding connections, finding his own staff was a peculiar hybrid of high-level interests and that there was a reasonhis bodyguard told him things.

The west coast was a damned mess, was what. The dowager hadn’t meant to get involved out here. She’d been on her way back to the East to spend a quiet spring. Tabini hadn’t intended to have his son come out herec

“Is the aiji protecting Najida?”

A nod from Jago. “Yes. Definitely.”

“And these four, with us?”

“Specialists,” Algini said.

Don’t ask, then. He didn’t.

But Algini said, further, “There are many more moving in, from all directions.”

Bren cast an involuntary glance at the windows. There was only rolling meadow. But they were not alone. Out in that landscape forces were moving, major forcesc and he had told Toby they would get Barb back. He had believed it when he said it. But the operation had just mutated. Tabini-aiji was backing them, all right, but suddenly the dowager’s phone calls to Shejidan and the Filing all made one piece of cloth. Tabini had behaved for months as if exile might have changed him, made him more timid, more willing to ignore longstanding situations, anything to avoid another conflict that might destabilize the government.