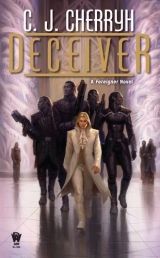

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Then a tap of the dowager’s cane. “We must let this gentleman get to his bed, paidhi-ji.”

“Indeed, aiji-ma.” As host, he made the suggestion. “Geigi-ji, please let my staff escort you to your rooms.”

Geigi’s bodyguard, among other things, had to be bone-tired, exhausted, after standing the last while, and those two still needed to brief and debrief with the rest of his aishid, and with the aiji-dowager’s people. Theyhad several more hours to go before they saw their beds.

“We are quite weary,” Geigi said obligingly, and in a series of small signals, the dowager gathering up her cane and signaling Cenedi; and Bren, as host, making a sign to Banichi and Jago, Geigi gathered his considerable bulk up from his chair, everyone got up, and there were goodnight bows all around as he left. Cajeiri and Barb and Toby hung back until the dowager and Geigi had gotten out the door.

For Bren, exhaustion came down on him, not just for this day, but for several days before. He waited while Cajeiri joined his bodyguard on the way out; and then heaved a deep sigh, feeling the effects of just about two sips too much brandy. “So sorry you have to hike down to the boat,” he said to Barb and Toby. And added: “Very well done, extremely well done. Frozen Dessert.”

They laughed, assured him an after-dinner hike wasn’t at all a hard thing for them, and he walked them to the door.

Then, in an attack of unease, and thinking of that long, dark set of steps amid the scrub evergreen, and that exposed dock below, he said to Banichi and Jago: “Nadiin-ji, one hates to ask, but would you go with them?”

“Yes,” Banichi said. “Let us pick up some equipment, and we shall be glad to do so.”

“I hate to bother them,” Toby protested. “Surely just house staff—”

“—is in no wise equipped to take care of untoward situations,” he said. “Indulge me. Geigi’s just arrived, with all that means. If our enemies aren’t asleep or more disrupted than we think, they’ll know he’s here, they’ll know meetings are going on, they’ll want more than anything to know what we’ve said, and I’m almost inclined to move out some more staff and house you two in the basement with Baiji tonight. Frozen Dessert, indeed. You’re too well informed. Scarily well-informed. And I don’t want the Marid getting their hands on you.”

“Is thatall?” Toby laughed. “I thought it was brotherly concern.”

“That, too, is somewhere in the stew. Just take the protection. And if you’re harboring any moresecrets, bring me up to date on them.”

“Oh, you knew we were running messages. Most of the time we didn’t have a clue about the content. At least on thisside of the water.”

“But you did know what Mospheira was up to.”

“Nothing not well-known now.”

“The Marid may not think so. You’re just a bit more fluent than makes me comfortable, brother. Unguessed talents.” That Toby had never outright told him how fluent he was getting– that bothered him; but Toby worked for Shawn, the President of Mospheira, the way he himself had once worked for Shawn in the State Department, and there were secrets and secrets in government employ.

“It’s getting better,” Toby said lightly. “I haven’t been around people talking before. I’m starting to pick out words. Figure out others.”

“I still can’t put a sentence together,” Barb said. “Toby’s far braver about that. But we absorb things. I’m picking up a lot about the boat from the work crews.”

“Well, you just be careful going down there, and get the hell away from dock if you don’t like the look of what’s headed your way. Even if you just get nervous. Stand off from shore and be ready to get out to the middle of the bay if you don’t like the feel of things at any time you’re down there. Better a little inconvenience than a mistake the other way.”

“Got it,” Toby said, and by then Banichi and Jago were coming back, carrying rifles, and with their outdoor jackets on– bulletproof and heavy as sin.

No surprise to Toby or Barb, who were used to Guild working gear. Bren saw them all out the door.

“Kindly go straight to the room and stay there, nandi,” Jago said.

“I shall,” he promised her. “Immediately.”

And he walked straight in that direction the moment the front door shut.

His two personal staff, Koharu and Supani, weren’t long arriving in his suite, a characteristic knock on the outermost door. Staff in the hall would have reported he was retiring, and his valets showed up almost before he’d gotten his own coat off.

He handed the garment in question to Supani, who hung it on a hanger, and that on a hook on the door: the coat would go away with them and come back refreshed and pressed by morning. Likewise the shirt and trousers and the ribbon that tied his queue, which he finger-combed out. He automatically sat down and let Koharu apply a brush to his past-the-shoulder hair.

Felt good. Took away tensions of the day.

Pop-pop-pop from outside. From down the hill.

Gunfire. He leapt up, headed for the other room and the door. Supani chased him down with a dressing gown and insisted on helping him.

“Tano and Algini!” he said, and Koharu understood and ran, outpacing him as he made the hall along with four of Ilisidi’s men and Cenedi himself, Cenedi giving directions as more of that company showed up from the lower hall.

Bren reached the library, where Tano and Algini still sat at stations and the two assigned to Cajeiri hovered by. “Get to the young gentleman!” Bren snapped, and those two went, leaving him room to reach Tano and Algini in the cramped quarters.

“Movement, nandi, down by the dock,” Tano said, “and up by the house.”

He didn’t distract them with questions: Algini was talking in code, probably to Banichi and Jago, maybe to units disposed about the grounds, and Tano’s eyes never left his screens.

“Sector 14 now,” Tano said into his own microphone.

Whether intruders were incoming or outgoing in sector 14 one had no idea, but it was too near the downhill walkway. Bren hovered and kept quiet. He could see that blinking sector for himself, some distance off the walkway where Banichi and Jago would be.

He didn’t know who had been firing, except the one from Ilisidi’s young men on the roof. He hoped it was Banichi and Jago taking a few shots at intruders and not the other way around. He hoped Toby and Barb kept their heads down. They hadn’t had time for it to be just Banichi and Jago on the return.

“Somebody should check the boats,” he muttered.

“Someone is doing that, Bren-ji,” Tano said. “Both boats. And our own perimeter.” His eyes never left the screens. “It may be diversion. We have called the village and set them on alert.”

Damn, he thought. The aiji’s men hadn’tcleared out all the problem. They’d gotten Kajiminda cleaned up, they’d gone after the lot down in Separti Township, but very possibly people had gotten out of Separti. Some might have escaped by sea, and some might have headed overland, to take the long land route to the Marid. Some might not have left at all, but gone to set up bases in the wild lands, the hunting reserves, between the coastal villages of Sarini Province and the Maschi territoryc bases that could continue to be a problem until hunted down.

How many Guild agents might the Marid have deployed in the district? Unfortunately, a lot, if one counted any Guild who had been supporting Murinic who might have headed down to the Marid as a way to escape retribution.

He really, really didn’t like that line of reasoning. He stood very still, just watching the retreat of intrusion in a series of lit-up squares. Which could be a real retreat, or simply designed to divert attention from something breaching their perimeter elsewhere.

He stood still so long his arm, leaning on Tano’s chair, began to tire, and his eyes, focused on those screens, to dry out from want of blinking. He shifted position slightly and did blink.

The Guild’s actions were like that. Patient waiting, interspersed with a few moments of adrenaline.

They were back to the patient waiting. Which was almost as bad as the adrenaline.

“Are our people safe?” he asked.

“All reporting, Bren-ji.”

Our peopleincluded his brother, Barb, and the two people he loved most in the world.

And the fact Tano and Algini were sitting there dead calm and completely unemotional meant only that they were on the job and not sparing a thought to personal relationships with anybody. They continued nonstop observing, listening and, with small key-clicks, aiming sensors and communicating with various people about the groundsc all of whom were evidently reporting in or responding in some fashion.

Bren waited for another length of time before saying, very quietly, without inflection: “If it is safer for Banichi and Jago to bring their wards back to the house tonight, we shall certainly find room.”

“It may indeed be safer,” Algini said, and plied keys, a series of fast clicks. He said then: “They agree.”

The next while, extricating two valuable and highly visible targets, namely two pale-skinned humans, from a difficult position on the lower walk—that took some time, and Bren stood and listened for part of it.

But then he decided he could be of somewhat more use than that, so he went out to the hall, and asked Ramaso, who had appointed himself to hall duty during the disturbance, to make ready two beds belowstairs.

“Indeed,” Ramaso said. “Please delay them with hospitality upstairs, nandi, and there will be space for them as fast as possible.”

“One doubts they will sleep immediately,” he said, and turned to find Antaro and Nawari both, one an emissary from Cajeiri and one from Ilisidi, and then Lord Geigi himself coming out into the hall, to find out what was going on. Lord Geigi, like him, was in his night-robe, but not, like him, with his hair undone. Bren felt a little heat touch his face, a little embarrassment at that, and so surely must Ramaso, but there were more important things afoot than a little impropriety. “Geigi-ji,” he said. “What a welcome we have given you!”

“My staff informs me your brother and his lady are turning back.”

“Indeed. It seems safer.”

“It must,” Geigi said. “Infelicity on the Marid and all its houses! No one will sleep for hours, and my fool of a nephew should not be the exception. Let your staff inform him I shall speak to him directly after breakfast and that the activities of his associates tonight have placed me in no good mood toward him! I would deal with him tonight, except I want my wits about me!”

The middle door opened. Cajeiri turned up, putting his head out. “Are we safe, nand’ Bren?”

“At the moment we appear to be, young gentleman. Go back to bed.”

Cajeiri likewise was in a night-robe, and barefoot, with hishair streaming over his shoulders.

And Ilisidi’s door opened. Cenedi himself arrived, in boots and trousers, and with braid intact, and obviously wanted answers.

“Nand’ Toby and Barb-daja are coming back to the house tonight, Cenedi-ji.” Which was stupid to say: of course Cenedi knew that part of it already. Guild in protection of their lord were never out of touch with the rest of their number. What Cenedi didn’t know was the arrangement he had just ordered in the household. “We are lodging them downstairs. If the dowager would wish a quieting cup of tea in the study, we might arrange that.” It came to him that, besides his study, which he needed for his own urgent business in straightening this mess out, they didhave the sitting room they could convert to sleeping quarters.

But that had its own necessary function in the house, the meeting place, the only place besides the dining room that could accommodate them all; and the dining room was just—not the place one discussed business. Impossible, he thought distractedly. And anyroom downstairs was bigger than the cabin Barb and Toby shared on the boat.

Two beds, he had told Ramaso. Were they going to think he was making a statement?

“The dowager will take tea,” Cenedi said, “but will not receive visitors tonight, nandi.”

“Mandi-ji.” Bren snared a passing servant, who skidded to a fast halt. “Tea for the dowager. Tea for any guest who wants it.”

“I shall take some myself,” Geigi said, “with teacakes, should there be any at this hour, nadi.”

“So would we like teacakes,” Cajeiri said. “My staff would, too.”

Where a boy Cajeiri’s size proposed to put more food after that supper, God only knew. “See to it,” Bren said to the servant, and as Samandri took out at all decorous speed: “Cenedi-ji, can your people supply security to the front door while we open it for Banichi and Jago?”

“We are already in position, nandi. And they are on their way.”

“Of course.” He found himself exhausted. “Forgive me, nadi-ji.”

“We are glad the paidhi has an accurate sense of these things,” Cenedi said diplomatically. “I shall see to the front door myself,” he added, “being in the vicinity. By your leave, nandi.”

“Please do,” he said. The others had gone back to their rooms. It was his job, as the lingering visible civilian, to get himself out of the hall and back out of the Guild’s way. The one moment that might provoke renewed attack, were there any enemy still in position, would be a door opening, and their guard needed no distractions in protecting them from more dings in the woodwork.

So he went back to the library, where Tano and Algini reported Banichi and Jago were now at the portico, and then that they were coming in. He watched the lights that indicated the opening and then the safe shutting of the front door, he heard the thump of the bar going into place, and headed back out into the hall again.

Banichi and Jago looked unruffled. Barb and Toby, in their company, were dirty and disheveled, their boating whites scuffed and bearing traces of dirt and evergreen. It was likely Banichi and Jago had landed on them, or thrown them into the bushes with a force they would have considered only adequate.

“Well, here we are again,” Toby said with a shaky laugh, “like bad pennies. Sorry about that, brother.”

“Just thank God you made it—and thank God I sent Banichi and Jago with you! Who fired?” The last he asked in Ragi, and Jago said:

“We did, nandi. We had a security alert, and a sure target. The dowager’s men are searching the grounds. They will report. We stayed with our principals.”

“One is profoundly grateful,” he said. “Are youall right?” Jago was nursing a stitched-up wound from the lastfracas. And one didn’t ask Guild to admit to injuries in outsider hearing, but Barb and Toby were not exactly outsiders, and Jago nodded with, he thought, honesty.

“One remains a little sore,” she said, “nandi. But their return fire was not accurate.”

“It might have been, without you. Thank you. Thank you profoundly, nadiin-ji.”

“Thank you,” Toby added in Ragi, on his own behalf, with a correct little bow, and Barb echoed, in fairly bad Ragi, but with the correct addition of a third—consciously or not, “Thank you two, and Bren.”

“Indeed,” Banichi said, returning the bow.

“Go where you need to go,” Bren said. There was debriefing yet to do, and two of Cenedi’s men had come into the hall. “Rest. We are guarded, here.”

Banichi smiled, a little amused at him, but he frankly didn’t care. He was tired, his guard was tired, and Barb and Toby had just been through enough to keep them awake the rest of the night. Servants had shown up. He said to them: “I shall see nand’ Toby and Barb-daja in my study while staff prepares their bath. Send another pot of calmative tea to my office. And brandy. They will surely wish to sit a moment.”

“Nandi.” Two servants sped on different missions, and Banichi and Jago had headed for the library/security station. Bren directed Barb and Toby to his office door, opened it, and brought them inside.

They took chairs, gratefully but cautiously. “I’m afraid we’ll get dirt on the carpet,” Toby said. “Let alone the upholstery. Is my backside clean?”

“Honorable dirt,” Bren said, a rough translation of the Ragi proverb. “The staff will gladly clean it, and the chairs are tougher than they look. There’s a bath downstairs. They’re setting up. I’ve ordered a sedative tea. It’s fairly strong. Harmless to us. And a very good thing at times. Add a shot of brandy and you won’t wake til morning.”

“I wished I’d had my gun,” Toby said, “which is, of course, down on the boat.”

“Well, well, but you’re on the mainland, where professionals handle that sort of thing,” Bren said. “Unfortunately it means professionals on the other side, too.”

“That’s certainly a downside,” Barb laughed. She moved to brush back her hair and she was shaking. She looked at her hand as if it were a foreign object and made it into a fist, resting on the chair. “I guess the other side isn’t through trying, is it?”

In that moment he forgave Barb a lot. He looked at the two of them, his quasi-ex and his brother, and saw a pairc not the woman he’d have picked for Toby, but then, Barb lent Toby just enough of her predatory selfish streak to keep him from flinging himself on grenades and Toby lent Barb enough of his sense of stability and loyalty to keep her better side in the ascendant. Toby the rock. Toby the damned self-sacrificing fool. Barb wanted somebody who’d always be there—even if she had to follow him in and out of irregular harbors under fire, as it appeared: this the woman who’d lived for nightclubs and fancy gowns.

“Good for both of you,” he said, and meant it fervently.

“Just so damned glad you sent Banichi and Jago.”

“I assure you, you and whoever else went with you would have been under watch the whole route down to the boat, but you don’t have my skills at falling flat in the dirt on cue.”

“I’ll be faster at it, after this,” Toby said. “ Banichishoved me flat. I think I’ll remember that fact tomorrow morning.”

Bren laughed, well familiar with that sensation, which involved the relocation of every vertebra in one’s neck and back, not to mention the meeting with the ground.

And just then a knock at the door heralded the servant with the tea service, the very historic tea service—the others must be elsewhere disposed—the cups of which Toby and Barb took with dirty fingers, ever so carefully.

“This is beautiful,” Barb said, looking carefully at the cup. Barb had an eye for assessing things. “But my hands are shaking.”

“They won’t, in a moment. Thirteenth century, that service. Best the house has. —Thank you, nadi,” he said to the servant. “Please wait.” And took his own sip of tea. “Your boat will be safe. Someone is checking out both the boats, yours and mine, just to be sure.”

“So grateful,” Toby murmured. “You think of everything, brother.”

“I have no few brains working on problems for me,” he said. “So I don’t have to be brilliant.”

“I never appreciated a house like this,” Toby said. “I’m starting to understand it. In all senses. It’s not all tea and cookies, is it?”

“It’s a village of its own,” he said. “It defends itself pretty well, and we all take care of each other. Staff smuggled most every stick of furniture and set of china, even whole carpets, out of my Bujavid apartment when the Bujavid was being taken over. They got it on trains right under the opposition’s noses and had it and key staff members collected here at Najida before Murini’s people knew they were missing. And some of my staff, Murini’s people would particularly have liked to lay hands on, but they weren’t about to come in here to get themc Najida being part of Najida Peninsula, which is part of the west coast, which is Edi territory, Murini didn’t want his agents cracking thategg, for fear of what might hatch and raise holy hell. But you know that, Frozen Dessert.”

“Even the Marid,” Toby said, “was scared to take on your staff.”

“I think so. They’d organized. That was everything. Favor Ramaso for that. Ramaso and his connections. No small advantage to me, in all this.”

One cup gone, and Barb stifled a yawn. “Oh, my God. I’m sorry, Bren.”

“That’s the intent,” Bren said. The sedative was hitting his system, too, and he set the precious cup aside on the desk. The attending servant, part of the furniture until that moment, instantly collected it, collected Barb’s, and Toby finished his in a last swallow and handed the cup over.

“Nadi,” Bren said, delaying the servant a moment, and gave him the incidental instruction to inform Geigi’s nephew that his uncle was annoyed as hell and would talk to him in the morning.

“So we’re downstairs,” Toby said.

“Two of the youngest servants will have given you their quarters,” Bren said. He could guess the names. “There’s the servants’ bath, down there, servant’s kitchen, where you may find snacks at any time of night—but just ask the staff. They’ll be happier to provide it for you on a tray.”

“Better than Port Jackson’s best hotel,” Toby said, and then realized: “I don’t have my shaving kit. Or either of us a change of clothes, what’s worse. Everything’s on the boat.”

“Trust staff. They’ll see to you. Pile your clothes outside the door and they’ll turn up clean by dawn.”

“God,” Toby said. “Thank the staff for us.”

“I have,” Bren said, and got up, as Toby and Barb levered themselves up with considerably more stiffness. “Soak in a hot tub, mandatory. Atevi manners. Then bed. You’re sleeping in a fortress. Let staff do the worrying tonight, too.”

“Good night,” Toby said, and hugged him, and Barb did, sister-like. Brother-like, he wanted to ruffle her hair, he was so pleased with her at the moment, sedative tea and all, but Barb was perfectly capable of building that gesture into a fantasy, and he didn’t want to upset the sense of balance they’d found, at least for the night.

“Good night,” he said, and showed them out into the hall, and pointed them the way to the downstairs, down by the dining hall, before he headed for his own room, and found his two valets on his track before he got there.

“Nadiin-ji,” he said, feeling warm and cared-for and very, very lucky. He let them rescue his clothes, and flung himself into bed on the aftereffects of the tea, eyes shut immediately.

Jago would come to bed soon. Her sleeping with him was the arrangement that let his staff fit into the library with their equipment. But he was too sleepy to wait for her.

7

« ^ »

Lord Geigi might have interviewed his nephew in his nephew’s room downstairs, and Bren had expected he would do so. But that venue would have been a bit cramped for the interested audience it turned out to have drawn—himself among them. Geigi had indicated the dowager would of course be welcome; and of course the paidhi-aji, and then Cajeiri had managed to attach himself to his grandmother, and they all came with their requisite security, six persons—Tano and Algini were on active duty with Bren this morning, while Banichi and Jago, avoiding formal uniform after a long day yesterday, stayed at the consoles in their station.

“There is the sitting room,” Bren said to Geigi, so the sitting-room it was, a natural enough retreat after a good breakfast—in which Baiji did not share. Geigi did not let anticipation hurry him at all. They quietly took tea once they reached the sitting room. They waited, and chatted about affairs on the station.

The mood was jovial, even—so pleasant that when the dowager’s guards—her personnel being in greatest abundance for such duties—escorted Baiji upstairs and into the sitting-room, Geigi scarcely paid him attention, savoring a last cup of tea, apparently indifferent.

Baiji was in a sad state this morning—sweating, as pale as an ateva could manage, and abjectly down of countenance. He gave a very deep bow to his uncle, who did not so much as acknowledge the fact, and quietly subsided into the chair the servants had placed central to the arc the other chairs, made the potential focus of all attention, if anyone had looked at him.

No one said anything for a moment. Baiji kept his mouth shut. Then:

“What happened to your mother?” Geigi asked directly and suddenly, and as Baiji immediately opened his mouth and started to stammer something: “Be careful!” Geigi snapped at him. “On this answer a great deal else rests!”

Baiji shut his mouth for a moment and wrung his hands, which otherwise were shaking.

“Uncle, I—”

“Who am I?”

“My uncle, lord of Sarini province, lord of Kajimindac”

“I am less than certain you may call me uncle,” Geigi said mercilessly. “I have not yet heard my answer.”

Baiji bowed his head over his hands. “Uncle, I—”

“My answer, boy! Now!”

“I fear now—one fears they may have killed her.”

“Do you, indeed? And is this a recent realization?”

“Only since I came here. Nand’ Bren said it, and I cannot forget it. Day and night, I cannot forget it! I am sorry, Uncle! I am infinitely sorry.”

“You disrespected your mother. You disregarded her good opinion when she was alive. You ignored her orders. You did everything at your own convenience or for your own benefit, with never a thought about her wishes or her comfort, or her respect. Am I mistaken?”

A lengthy silence, while Baiji studied the carpet in front of his feet.

“I regret it. I regret it, honored Uncle. I wish she were alive.”

“So do I,” Geigi said grimly. “But I would not wish her the sight I now have of her son, nadi.”

“Uncle, —”

“Do not appeal to me in her name! You used up that credit long ago. Muster virtue of your own. Can you find any to offer?”

“I see my faults,” Baiji said weakly. “Uncle, I know I am not fit to be lord of Kajiminda.”

“No, you are not. Have you any interest in becoming fit for anything?”

“The aiji-dowager has suggested—”

“I know what she has suggested.”

“One would be very glad of such terms.”

“I daresay you should be. Liberty there will not be, not until we have unraveled this mess you have made. Have you any excuse for yourself?”

One sincerely hoped Baiji had the intelligence not to offer any. Bren sat biting his lip on this untidy scene and watched Baiji bow repeatedly.

“One gave the papers to nand’ Bren. One saved every shred of correspondence with these people in the Marid.”

“Self-protection and blackmail hardly count. Had you attempted to use such things from the position you had made yourself, you would have been dead by sundown. You hardly have the courage to have taken them to Shejidan and given them to the aiji. Did you attempt that?”

“One feared he would not view them in any good light.”

“One doubts there is a light in which to view them that would cast you in any credit whatsoever. I shall offer you several suggestions, the first of which is that you abandon any illusion you ever will rule anything.”

“Yes, Uncle.”

“The second is that you do not attempt to negotiate with anyone in secrecy from me and from the aiji-dowager, who has offered a handsome marriage for you, and the saving of your life.”

“One would be grateful, Uncle.”

“Did you hear the first part of that? Do I need to break it down for you?”

“I shall never deal with any other people, Uncle.”

“The third is that you take pen and paper to your room and begin a list of every name you know in the Marid, every person you have had contact with directly or indirectly, including subordinates and Guild. Have you had any message from my former wife?”

“No, Uncle. Not directly.”

“Indirectly.”

“She—she vouched for the first person to contact me.”

“Who was?”

“Corini of Amarja.”

“How good is your memory, nephew?”

“I can remember the names, uncle.”

“I suggest you go do so. The marriage that will be your sole salvation depends on the output of your memory and the speed and accuracy of your writing. Do you understand that? Make every connection clear. Provide us your best estimate of these connections and differentiate the ones you know from the ones you suspect. Provide us a list of the things they offered you, and the dates so far as you can reconstruct them, and no, you may nothave access to the documents you provided to nand’ Bren. Let us see the quality of your memory and the functioning of your wit. It may be instructive for you.”

A deep bow, clasped hands to the forehead in profound apology. “I shall, Uncle. I shall. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.”

“What have been your dealings with Lord Pairuti of the Maschi?”

“None.” A deep breath and shake of the head. “He commiserated with me about my mother and wished me well on my taking up Kajiminda. That was all. He never helped me. He never came to call.”

“Nor did you call on him? It would have been courteous.”

“I intended to, Uncle.”

“Appalling,” Geigi said with a shake of his head, and looked toward Ilisidi. “Does the aiji-dowager have any questions for this infelicitous person?”

“One believes you are setting him on a useful program,” Ilisidi said, and looked at Cajeiri. “Great-grandson, this is a bad example. Have youany advice for this wretch?”

“He should obey his uncle,” Cajeiri said.

“Good advice,” Ilisidi said. “Very good advice. —Do you hearit, nadi? One recommends you hear it!”

“One hears it,” Baiji said faintly. “One hears it, aiji-ma.”

“Go,” Geigi said with a wave of his hand. “Go downstairs! Begin your writing! Immediately!”

Baiji gathered himself up and bowed three times, to Ilisidi, to Geigi, and to Bren, then headed to the door—Guild instantly positioning themselves inside and outside to make sure he made it to the door without detours. Ilisidi’s young men gathered him into their possession in the hall, taking him back to his cell in the basement, and Geigi let out a long sigh, shaking his head.

“Time has not improved him. One hoped, during the time we had no communication. One hoped, having no better choice when the shuttles were not flying—but that I believed his unsubstantiated reports that things were in order—it was my fault, aiji-ma. I left him in charge too long.”

“If you had come back to Kajiminda while he was in charge, you would surely have died,” Ilisidi said, “whether or not your nephew was in on it. About that, we make no judgement—yet. One only offers belated condolences for your loss, Geigi-ji.”

“It will be my highest priority, aiji-ma, to find out what happened—starting with my staff. There is no word of them? No word, perhaps, from the Grandmother of Najida? One hopes she is not too put out with me.”

Bren started to say he had had no word. Ilisidi said, crisply: “After lunch, one believes.”