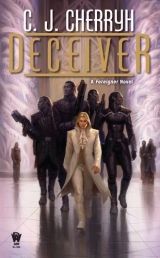

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“Go,” Bren said.

“Nandi.” With a bow of his head he ducked down toward the exit, limping, looking very young and pitiable at the moment.

Bren watched him go with painful sadness, but very little regret for the decision—not when the boy’s lack of judgement could jeopardize other lives, and the mission, and compromise the aiji’s integrity. There was one thing—one helpful thing the boy could do, put Geigi wise to the fact the bus was not coming back, so that Geigi would not be phoning Najida and putting sensitive information onto the phone lines.

Beyond that—

We are going to die, Bren thought, trying out the thought. I am taking Banichi and Jago and Tano and Algini into a situation I don’t know how to get us out of. And if we do survive this, that poor kid’s look is going to haunt me so long as I live.

He chanced to meet Algini’s eye. Algini nodded once, grim confirmation of his dealing. A sweep of his glance left met Banichi—with the same expression.

And in that same interval, while the bus was stopped, Damadi came down the aisle. Alone.

“Nandi,” Damadi said with a little bow, “we are with you. Your orders are the aiji’s orders.”

That many more men and woman were all in the same package. All at extreme risk. All his responsibility.

“My extreme gratitude,” he said. “Thank them. Thank them all—for myself and for my bodyguard.” If there was a chance of getting out alive if things went wrong—it was in numbers. It was in covering fire.

It meant losing most of these people, if he failed. They would try to keep himalive. And it was not a priority he wanted.

He leaned forward to speak to the driver. “Carry on, nadi. Mind any disturbance of the road surface. There was a mine today on Najida road.”

“Yes,” the driver said. He was himself one of Tabini’s men.

Bren straightened up again, caught his balance with the upright rail as the bus resumed its bumpy, headlong speed.

Toward Tanaja. Toward the largest capital of the Marid, a place he had never in his life wanted to see up close.

He sat down, and his bodyguard clustered together over in and around the opposite seats, talking in low voices.

Which left him to consider what he was going to do so as not to die, along with everybody else in his charge.

That meant communicating with Tanaja beforetaking this bright red and black bus full of Tabini’s Guildsmen deep into the Marid.

And that meant having something eloquent to say in the very little time Machigi might listen.

He didn’t have his computer with him on this trip. It, and all the sensitive information it contained, including reference materials that might have been useful at this point, were back in Najida. That was probably a good thing.

He had, however, a small notebook in his personal baggage. He got up, got that out, and settled down, extending the tray table for a work surface.

He wrote. He outlined. He lined things out. He went to a new sheet, and finally, as Banichi and Jago returned to their seats opposite himc

“One is appalled, nadiin-ji,” he said, “one is extremely distressed at the situation. One is willing to go, but the risk to my aishid is entirely upsetting to me.”

Banichi shrugged. Jago said, “The aiji-dowager has not done this lightly, and the support of the aiji’s men lends us a certain moral force, Bren-ji. The sheer number of us and the man’chi involved is considerable. We are gratified by their confidence in us.”

“Survival is a high priority in this undertaking,” Bren said. “Your own as well as mine—and that is not only an emotional assessment. Your knowledge, your understanding of situations in the heavens, among others, cannot be replaced in the aiji’s service.”

“Our immediate priority,” Banichi said, “is your survival, Bren-ji, and please favor us with the assurance you will nottake actions contrary to ours. By no means rush to our rescue.”

He had done that silly thing, among the very first things he had ever done with them. They had never let him forget it.

“One is far wiser now,” he said, “and one offers assurances I shall not.” He moved a hand to his chest, which hurt with every breath. “I am wearing the vest, nadiin-ji, and shall wear it in the bath if you ask it.”

“You will not need to go that far,” Jago said, “if you use your skill to keep us close to you. Do not let them separate us, Bren-ji, or disarm us. If they attempt that, be certain from that point that they mean nothing good, and harm is imminent, to all of us. At that point, if they move on us, we must take action.”

“One understands,” he said. He took comfort in their presence and their calm, utterly outrageous confidence. He didn’t know where they got it, whether out of being what they were, atevi, and Guild, or out of the moral character he knew they had.

Their devotion, their emotionally driven man’chi, was his. He was absolutely sure of that. There was no division between them.

“I am going to get us out of this alive,” he found himself saying. “I need to contact Machigi himself. How can we go about this, nadiin-ji? Should you initiate the contact?”

“That would be advisable under most circumstances,” Banichi said. “We can do that, Bren-ji, Guild to Guild. We can attempt to get information in the process.”

“I need to know,” he said, trying to think through things in order, “if they are aware of the mine on the Kajiminda road and the kidnapping of the child. One assumes they are. I need to know if they are aware that the Guild Council is meeting on a question of outlawry. One assumes they have the means to know it.” The Marid Guild had been outcast, though not in legal outlawry, for months, as far as their being accepted in Guild Councilc those members of the Guild who had been supporters of the Usurper were now, so far as he knew, Machigi’s, since Tabini’s return to power. That was surely partof what was driving Guild deliberations, now. “How close contact can they maintain with the Guild in Shejidan?”

“Likely,” Jago added, “the Kadagidi clan Guild that have fled down here will maintain kinship contacts up in the central districts. And one naturally expects them to know any news that has gotten to Separti, where they have informants.”

“Find out. And advise them that I have a message for Lord Machigi and wish to speak to him personally.”

That should be enough to get the attention of a sane man who had any awareness he was in a trapc except, one could not help but think, Machigi was a very young man—in some ways reminiscent of the young man he had just dropped off the bus.

Young, brilliant, so gifted that he had not tolerated many advisers, so confident that he had offended many of his peers —and perhaps now found himself the target of a move both underhanded and well-planned by far older heads: not smarter men, but more experienced. He had never seen a photograph of Machigi. In his mind’s eye he kept substituting Lucasi’s face in that moment Lucasi had descended from the bus– and that was a mistake. That was a supremely dangerous thing to do.

It gave a faceless opponent an imaginable face, one whose reactions he could imagine.

Imagine. That was the trap. He could lose this mission by a mental lapse like that, but once he had thought it, he had trouble shaking the image. That was precisely the age.

Arrogance. Inexperience. Brilliance. All in one hormone-driven, unattached package. An aiji had no man’chi. He got it from below. And that made him hard to predict.

Machigi would be irate, granted the dowager was right and some other lord of the Marid clans had not only defied him, but actively moved to plunge him into serious difficulty. He would be irate and he would not necessarily know who his enemy was, nor how many of his association might have turned on him.

He would also be, quite likely, embarrassed to be caught without knowledge. He would be in a personal crisis as to how others thought of him, and he would be touchy as hell about exposing that weakness to his enemies and to his own people. The machimi plays, that guide to the atevi psyche, had had that as a theme more than once. Man’chi had turned, not to be directed to him. He was not as potent a leader as he had thought, and now everyone could see it. Others might be talking about him. The servants might become uncertain in their dedication. His spouse, if any, might be reassessing her marriage contract and talking to her kinfolk. It was a potentially explosive situation—both inside Machigi, and inside Machigi’s house, once it became known he had been this egregiously double-crossed.

Granted, still, that Ilisidi was correct in her assessment of him.

If she was not, and Machigi really had committed that foolish an act as to order Guild to violate Guild rules, then Guild action would have to take him out.

Unfortunately none of them on this bus would live to see it.

It was going to take a while for Banichi to get through to somebody in Tanaja, quite likely.

And then there might be some little time of back and forth communication between the bodyguards before two lords ever got into dialogue.

So he had time to think. He needed desperately to concentrate, and simply stared at the road ahead, past the seats Banichi and Jago had vacated.

The people he loved most in the world—and this time around, he had to defend them. He had to be smart enough first to figure Machigi accurately and then to get a self-interested and arrogant young lord to do a complete turnaround in his objectives, his allegiances, and his—

Well, Machigi’s characterwas probably beyond redemption. He would beno better than he had ever been. The question was, in self-interest, could he actin a way compatible with the interests of the aishidi’tat?

How could he achieve that? Machigi would, assuming he was acting sanely, act in his own best interest. That interest had to become congruent with the interests of the aishidi’tat. And Machigi had to perceive that to be the case.

And the situation wouldhave an explosive and embarrassing emotional component: he had first to make Machigi aware of the situation with the Guild, if he was not aware already, and avoid Machigi’s indignation coming down on him as the bearer of bad news. He could not seem to despise Machigi in any regard.

But neither could he afford to be intimidated. And it was a good bet Machigi would try to do that.

He thought of the approach he would make.

Getting into Tanaja alive was first on the list.

What did they know about Machigi’s character? Without his computer, he had to haul it up from memory, and arrogant, ostentatious, argumentative, and ruthlesswere at the top of the list.

Young, brilliant, and unaccustomed to failure or reversal.

Ambitious, and already at the top of the Marid power structure.

Challenged from below, really, for the first time.

Humility was going to win no points with this young man. Brilliant?

What about educated?That was different than brilliant.

An education about the world outside the Marid would be an asset. He couldn’t remember data on that. But Machigi, like most Marid-born, had never been outside the Marid. His world experience was somewhat limited. Ergo his education was somewhat limited. He would not have seen things to contradict his own ideas.

Bad trait, that.

One couldn’t attempt to intimidate him with education: he wouldn’t recognize conflicting data as more valid than his own.

It was a difficult, difficult proposition, this mission.

“Nandi,” Tano said suddenly, having been listening to something for a few moments. “Nandi, Banichi has gotten to the lord’s bodyguard. He has gotten them to advise their lord you wish to speak to him on a matter of importance.”

Get ready, that meant. He straightened his collar, his cuffs, as if Machigi could be aware of that detail; but he was, and it set his thoughts in order.

Points to Banichi, if Banichi could get this man to talk in person. It would be damned inconvenient to have to conduct this argument relayed through his staffc a process that could go on for hours and end up with a number of important points taken out of order or lost entirely.

Fingers crossed.

He shut his eyes and waited. Sixty. Fifty-nine. Fifty-eight.

He got to minus twenty, and Tano said: “The lord will be available momentarily.” Tano passed him an earpiece and mike, across the aisle.

That was actually amazingly fast. Machigi had pounced on that one. Interesting. Encouraging, even.

Curiosity, maybe. A burning, though predatory, curiosity.

And now there was a very delicate protocol involved. One could not be waitingfor the other. And one could not be madeto wait for the other, not without creating serious problems from the start. Algini, with his own headset, was listening, and held up a finger to signal that, by what he heard, the lord was very likely about to take up communication. Two opposed security teams were required actually to cooperate to achieve simultaneity.

He put on the headset. Tano signaled him.

“Nand’ Machigi?” Bren asked.

“ Nandi,” came the answer, a young voice with the distinctive Marid dropping of word endings. “ You are on our border.”

“It is our hope you will favor us with a meeting, nandi. More than that one should not say in this call. We ask a truce and safe passage to Tanaja, and a personal meeting at the earliest.”

A lengthy silence. “ Interesting.”

“My office is not warlike. Discussion will be, one hopes, of mutual benefit. We ask your active and constant protection on the road to Tanaja, nandi, for very good reason.”

A second, shorter silence. Then: “ Come ahead, nand’ paidhi. You have our assurances.”

That simplified things. One stipulated the road toTanaja. That got a yes.

Getting out againc he would have to manage that when the time came.

“One looks forward to our meeting, nandi. Let communication pass now to staff.” He handed the equipment back to Tano, and Tano resumed listening. Doubtless Banichi, in the rear of the bus, was handling the specifics.

Bren drew a long breath, thinking of Najida at the moment, his pleasant little villa above a sunny bay. He thought of the dowager and Cajeiri. Of Hanari and Lord Geigi, who would have to pull together a staff and a defense, in a house where Machigi’s agents had just been. No little bloodshed there, warfare right on the threshold of the Marid, lives lostc

Lives damned well wasted in the long, long determination of ambitious lords to take the West and set up some power to rival the aishidi’tat.

Medieval thinking. Medieval ambitions. Modern ships could power their way around the curve of the coast and see with electronic eyes, could trade, and fish, and prosper on a par with the rest of the aishidi’tatc if the Marid ever joined the rest of the world and modernized.

But the seafaring Marid, still locked in the Middle Ages, still spent resources on its fleet, on its old, old ambition for dominance of the southwestern coast. Eastward—eastward on that southern side of the continent, starting from the Marid, there were no harbors, except one sizeable island, which the Marid had: but all along that coast eastward of the Marid was the history of geologic violence—sunken borderlands, swamps, abrupt cliffs, leading toward the forbidding East itself, which was one rocky upland after another. The Marid had long seen westernexpansion, around the curve of the coast, as their natural ambition.

But technology could do so much more for them. Access to space—the ultimate shift in world view that happened among atevi who couldmake that transition—

Giving the Marid more advanced tech, however—that was a scary proposition. In point of fact, the scholarly traditionalists of the north had nothingon the grassroots conservatives of the South, when it came to the fishermen, the craftsmen, the tradesmen and armed merchantmen who, point of fact, had not greatly changed their ways or their world view since beforethe first humans had landed on the earth.

What else did he know?

That there was no educational system in the Marid, per se. The whole Marid worked by apprenticeship and family appointment. The classes of the population that needed to read and write, did; the classes and occupations that could get by with the traditional sliding counters and chalk ticks on tablets– did.

Taxes were whatever the aiji’s men said you owed.

Justice was whatever the aiji or his representatives or the local magistrates said was just.

It wasn’tShejidan. Not by a long shot.

And the Marid as a whole hadn’t been interested in having literacy spread aboutc certainly not by the importation of teachers from the north; and there was no way the local educated classes were anxious to teach their skills to the sons and daughters of fishermenc any more than most of the sons and daughters of fishermen were inclined to press the issue and leave their elders unsupported while they did it. Especially considering custom would keep them from using that education, and oppose their intrusion into other classes.

A medieval system with a medieval economy that was linked by rail and sea lanes to the far more modern economy of the north. The Marid had always been capable of sustaining itself, if it was cut off. It didn’t buy high-level technology. There probably was no television in Tanaja. There was radio. There certainly was armament, some of it fairly technical, imported by one class that wastechnologically educated: there were from time to time fugitives from the northern Guilds, who, rather than face Guild discipline, had offered their services in the South, and lived well. Lately there had been a fair number in that category, fugitives from the return of Tabini-aiji to power. There would be various Guilds in the court of Machigi and his predecessors, and elsewhere across the Marid—Guildsmen, who did the unthinkable, and trained others outside their Guild without sanction of the Guilds in Shejidan. In every period of trouble, there had been the fugitives who had taken formal hire with the various Marid aristocrats. There had been Assassins to make forays against lords of the aishidi’tat.

Or each other.

Always ferment. Always some military action brewing, or threatened, or possible.

It was a long, long history: the Marid exited its district to create mayhem in some district of the aishidi’tat. The aishidi’tat retaliated, occasionally sent in a surgical operation to eliminate a Marid lord, to adjust politics at least in a quieter direction.

Nobody, however, had ever “adjusted” the Marid out of the notion of taking the West Coast.

He couldn’t think about failure. He hurt like hell. Breathing hurt if he moved wrong. He could be scared if he let himself, and that was guaranteed failure. He was likely to be tested. He was likely to be threatened. And he was feeling fragile. He had to rid himself of that.

Was Machigi a good lord or a bad one?

A bad one, in the sense of corrupt and self-interested, might actually be easier to negotiate with. A good one, in the sense of looking toward the benefit of his own people, would be harder to compass, in terms of figuring out what his assumptions were and what his concerns were.

A bad man would have a far simpler endgame, one that might be satisfied by personal gain. And quite honestly, nobody had ever wholly discerned Machigi’s personal character.

Was Machigi truly as brilliant a young man as rumor said or in some degree a lucky one?

Was he, if brilliant, a tactician or a strategist? Brilliant in near-term results—or in long-range planning?

Was Machigi that rare young man with the nerves for long-term suspense, or would he act precipitately?

Was he traditionalist? Rational Determinist, like Geigi? Or a thorough cynic and pragmatist?

He did wish he could pull down what Shejidan might have.

Banichi and Jago came back to their seats, opposite him.

“Were you possibly able to read the household in that call, nadiin-ji?” he asked.

“One found them well-ordered, and run from the top,” Banichi said.

That was a point.

“How much initiative within his staff?” he asked.

“Communication went fairly directly to his aishid, and from his aishid to him.”

An admirable thing, correctly sifting out an important communication and speed in their lord knowing it. A lord with his hands on all the buttons, it seemed. Nobody had presumed to stall the communication. Therefore a lack of handlers. That might be in their favor.

He said, somberly, “One apologizes in advance, nadiin-ji, for bringing you into this kind of hazard. And no one could be more essential to any hope of success. I do not expect you infallibly to get me out alive and I know you understand in what sense I mean it. I do expect that if the worst happens, as many of you as possible will get out and report where it counts. Other than that, I give no orders.”

“We know our value,” Banichi said. “And we cannot give an impression of being willing to tolerate provocations, Bren-ji.”

“One trusts absolutely in your judgment,” he said. “But take no action that you can avoid. In this, and with greatest apology, if something untoward happens, let me attempt to deal with it first. If I am threatened, I shall take your abstinence as a sign that a reasonably intelligent human shouldbe able deal with it.”

Banichi actually laughed. So did Jago.

“We are in agreement,” Banichi said. And then said soberly: “You will do your best, Bren-ji.”

“Yes,” he said, with a very hollow feeling in his stomach. “Yes, I shall.”

21

« ^ »

Nand’ Toby had waked. So Antaro said. And Cajeiri went to his bedside to see, and to sit for a moment. Things upstairs were justc scary.

Very scary. And he was going to have to lie as well as he had ever lied in his life.

“Nand’ Cajeiri,” Toby said to him when he sat down there, spoke very faintly, but then cleared his throat a little and lifted his head.

“Quiet, nandi,” Cajeiri said. “Nand’ Bren said you stay in bed. Sleep.”

“Tired of sleeping,” nand’ Toby said, but his head sank back to the pillow. “Where’s Bren? Has he learned anything?”

Words. Words that never had come up between him and Gene and Artur on the ship. He understood the question. That, at least.

“He went to Targai. He follows Barb-daja. He looks for her, nandi.”

“No word from him?”

He shook his head, human fashion. “He’s busy.”

“Damn, I want out of this bed. I think they gave me something.”

“You sleep, you eat, you sleep. Antaro, did the kitchen send anything?”

“One can go get something, nandi.”

“Yes,” he said, and Antaro slipped out the door and shut it.

“It’s been quiet for a while,” Toby said. “I heard something blow up.”

“Long way.” The ship had never had words for long distances inside. Just fore and aft. Deck levels. “Out—” He waved a hand toward the road, generally. “Far.”

“Somebody was hurt.”

“Nand’ Siegi fixed them.”

“Good,” nand’ Toby said. “No word on Barb?”

He shook his head. “No. No word.”

“Bren safe?”

“Yes,” he said. “Banichi and Jago go with him.”

“Good,” Toby said. He seemed to be drifting again, then woke up, lifted his head, and looked around him a little. “Where is this?”

“Safe here,” Cajeiri said. And pointed up. “Dining room.”

“Ah,” Toby said, as if that had made sense to him. He lay back, breathing deeply. “You’ve been here a lot.”

He understood all of that. “Nand’ Bren said stay with you.”

“Thank you,” Toby said in Ragi.

He wassomebody important, too important to be on errands, there was that. But he was proud when nand’ Toby said that.

“Good,” he said in ship-speak. “Damn good.”

Nand’ Toby thought that was funny for some reason. At least nand’ Toby grinned a little, which reminded him of nand’ Bren. Toby was dark and Bren was gold, but in that expression they looked a lot alike, very quiet, a little shy, and totally lighted up with that grin.

He knew far, far too much of what was going on to be comfortable lying to nand’ Toby. He was glad when Antaro came back with a cup of soup and some wafers and gave them something specific to do.

Nand’ Toby drank half the soup and ate one wafer, and said he wanted more later. So he was getting better.

There was that.

But talk with nand’ Toby was difficult and full of pitfalls, and finally he said, to dodge more questions, that he was going to go upstairs and see if there was any news.

He took his time coming back down. There was nothing more to hear anyway, except that nand’ Bren had crossed into Marid territory. He was very relieved nand’ Toby had gone back to sleep.

The land sloped generally downward, and the road, as such, was a grassy track, about bus-wide, between low scrub evergreen. Limestone took over again from basalts, old uplift, old violence.

It was not a maintained roadc but there had been vehicle tracks pressing down the grass and breaking brush in the not too long ago—perhaps traffic that had come from Targai, or to it.

There was no other presence as the sun sank behind the heights. There was a scampering herd of game, and once, rare sight in the west, a flight of wi’itikin from a fissured cliffside. Bren noted that and thought of the dowager, who aggressively protected the creatures in her own province. Ilisidi would approve of that, at least.

The clouds above the western hills turned red with sunset and the driver had turned on the headlamps by the time they came on the sea—a startling vista, stretching from side to side of the horizon: that much red-lit water, and a few small islets, within shadowy arms of a large bay.

Lights sparked the dimming landscape, some near the water, more clustered somewhat inland.

“Tanaja,” Bren said, and Banichi and Jago, who had been catching a nap he envied, woke and turned to see.

Most of the bus had been nappingc the ability of the Guild to catch sleep where it offered was remarkable; and the bus had been silent the last couple of hours, Guildsmen taking the chance to rest now: tonight—

Tonight, none of them could vouch for. Wake us when we come downland, Jago had said; and he just had, faithfully.

Tano went back and waked others. Algini, who had slept only intermittently, did something involving the communications, possibly relaying a message through Targai, possibly just checking, Bren had no idea.

The driver—the third since they had set out this morning– stopped for long enough to trade out, possibly himself to catch a little nap. Bren earnestly wished he could, but napping under such circumstances had never been a skill of his.

He simply sat and watched Banichi and Jago and Tano and Algini consulting together, over at Tano’s and Algini’s seats; and was aware that Banichi went back to consult Damadi. Otherwise he simply watched those distant lights get closer, and brighter in the declining light.

Then there was a sudden flare of white light ahead, twin headlights. Some vehicle had been waiting for them—a bit of a surprise to him, but not, he would wager, to his aishid, nor to the aiji’s men.

The bus came to a slow halt, and opened the door, and two shadowy figures walked into the bus headlights, silhouetted against their own, coming from a truck parked across the road. Those two walked up to the side of the bus.

Banichi ran things now. Banichi instructed the driver to open the door, and one Guildsman mounted the steps and stopped, silently looked toward Bren, and with a sweep of his eyes, scanned back toward the rear of the bus. The aiji’s men had all stood up. The tension in the air was considerable. But no hands went to weapons.

Bren stood up slowly, facing the Marid Guildsman, who gave a barely discernible nod of courtesy. Bren returned it, as slightly. Then: “Follow us,” the man said, and turned and walked down the steps again, rejoined his partner and returned to the truck.

They hadn’t asked anything provocative, such as the paidhi-aiji leaving his protection and coming with them—which they would not have gotten.

They hadn’t shown a weapon.

Bren sat down without comment, and Jago sat down opposite him while Banichi instructed the driver to do exactly what the man had asked, and follow the truck. Its headlights lit dry grass, and swept over rock as the truck completed a turn, and then the bus started moving.

Banichi sat down.

“That didn’t go too badly,” Bren said.

“Trust nothing, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “This is not a place to trust.”

“One understands, emphatically, Nichi-ji. But well done.”

Banichi shrugged. “Thus far,” he said, and that was all.

The dark was full now, with a bright moon in the sky. The lights picked out tall grass, or brush, or occasional pale rock, and the pitch of the road was generally downward toward the distant, moonlit bay. They crossed railroad tracks, and then Bren had an idea they must have arrived very near the city, and he had a notion their position was fairly well on the northern side. He knewthe maps. He knew the rail routes from years ago, the old theoretical arguments with the Bureau of Transportation. It was a curiously comforting sense of location, as if something had become solid.

A turn in the road brought the city lights much, much closer. He knew absolutely where he was.

And wished himself and everyone on the bus almost anywhere else.

Panic would be very, very easy. But this was not a hazard the Guild could solve, short of turning about and making a run for the border, which was hardly sensible at this point. They were here. They had chosen to be here, on the dowager’s order, and there was nothing for it now but for the paidhi, whose job it was, to collect his wits and put himself together.

Calm. The first thing was to make sure the meeting took place.

The next thing was to make sense to someone from a very different region and bearing a centuries-old resistence to everything he represented.

It could be done. All of diplomacy was founded on the notion that it could be done.

He had talked to the alien kyo. He had made sense of Prakuyo an Tep. Could Machigi be that difficult?

Probably. Prakuyo an Tep had owed him a favor, by Prakuyo’s lights. It was not exactly the case with Machigi.

Curiosity, however, was an attribute generally of the intelligent—and nobody had ever accused Machigi of being stupid.

Insecurity was another probability: Machigi was young. Insecurity meant instability. Not set in his ways, at least. But prone to skitter off mentally onto unguessable tracks. His time-scale and expectations, too, would not be that of a mature man.