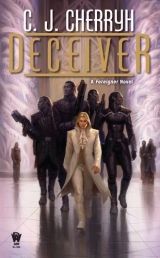

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Well, well, the aishidi’tat was still suffering aftershocks from the earthquake of Tabini-aiji’s fall and his triumphant, popularly driven return, and in some ways that popular mandate was still empowering the regime to fix things.

It was an old, old wound, the two exiled atevi peoples from Mospheira, essentially being the west coast of the aishidi’tat, yet being governed by other, continental, clans—while coming under perpetual assault from their old enemies in the Marid—

Well, things were going to change, if change didn’t kill them all.

Certain interests were going to have a howling fit.

“Well done, Geigi-ji,” Ilisidi said. “Bravely done.”

Geigi gave a small, dry laugh. “Now we have only to inform Maschi clan,” he said, “that I have given away half the peninsula.”

“Let Maschi Clan be very careful,” Ilisidi muttered ominously. “We will speak to them, Geigi-ji, should the Guild of Maschi clan at Targai want more information.”

“Aiji-ma,” Geigi said quietly. Ilisidi was taking actions in which her grandson had not been consultedc actions that could shake a quarter of the continent.

But then, her grandson had left her here. Withhis heir. Tabini was just about on Ilisidi’s scale when it came to forcing his way on the world.

Bren had personally dreaded the upcoming legislative session, and his own part in it—which involved the proliferation of cell phones. Now he was less sure they were even going to get around to debating cell phones, once the matter on the west coast hit the floor.

And Lord Geigi said: ‘“Sidi-ji, I must deal with Maschi clan, andthe Guild that serve there. One owes one’s clan that, at least, amid the honors Ragi clan has given. I must be the one to deliver this news.”

“Then do it by phone!” Ilisidi snapped—an earthquake of a statement from one of the most conservative, traditional forces in the aishidi’tat.

Geigi shook his head. “ ’Sidi-ji, you know I cannot. I must tell him. I must tell him soon. That was the price of so advising the Grandmother—and one knows Pairuti will not be pleased with me.”

“If he is wise, he will be pleased!” Ilisidi said. “Or you will takethe clan, Geigi-ji. We needthe vote!”

“Aiji-ma,” Geigi began to protest.

“The Marid will take him,” Ilisidi said, “or we do. Pairuti is a weak stick. This arrangement cannot lean on his good behavior.”

“Aiji-ma,” Geigi said in despair.

“And you may advise him of thatby phone, if you take our advice! And summon him to Kajiminda!”

“One cannot, one cannot, aiji-ma, for my own honor, and Maschi honor, most of all, one cannot. I must give him a chance, with his dignity, for his honor, and mine.”

“ Hishonor!” Ilisidi said darkly, and leaned on her cane and frowned at him, and frowned at Bren, and then at nothing in particular. She drew herself up then, and the cane tapped softly, once, twice, three times, and her jaw set. “He surely knows that you are back on the earth, he surely knows that Kajiminda is in distress—oh, we cannot believe that he is under-informed, and where is any message from him? We see none.”

“There has been none, aiji-ma,” Bren said.

“Well, if you must do it, Geigi-ji, prepare to do it in style. And nand’ Bren will assist. He is a persuasive sort. Will you not assist, nand’ paidhi?”

Bren bowed his head, said, “Aiji-ma,” and thought to himself—Ilisidi had just gone secretive on them.

“The lord of Kajiminda must sitin Kajiminda again, nandiin-ji,” Ilisidi said. “From therehe most reasonably would depart to visit Maschi clan. Nand’ paidhi, you have a bus.”

“At nand’ Geigi’s service, and the aiji-dowager’s, of course.”

“We have some few things to arrange,” Ilisidi said, flexing her fingers on the knob of her cane. “We have some calls to make, but, Geigi-ji, youmust simply rest and let us arrange them.”

“Aiji-ma,” Geigi said with a little bow. “But I must send messages.”

“One is certain they will be discreet, and wise. Nand’ Bren will assist you, making any contacts you need.”

“Without doubt, aiji-ma,” Bren said, but was not certain she even heard him.

Ilisidi was already, in her mind, setting something in motion, and it was a fair guess that Geigi’s honor would not like to know too much right now.

That, or Geigi had just made the requisite formal protest– for his honor’s sake—before undertaking something his honor found difficult. He wasa Rational Determinist, a philosophy which relied less on Fortune and Chance, that baji-naji attitude of the traditionalists. In his beliefs, he could shove Fortune into motion; and he had just made his own proposal to the Grandmother of Najida, generous beyond anything reasonable.

And, what was more, one suffered more than a slight suspicion that Geigi had not at all surprised Ilisidi when he had done it.

9

« ^ »

Lucasi and Veijico were not entirely happy. They had, of course, been listening at the door during mani’s session with the Grandmother and Lord Geigi, but they had not been pleased with being relegated to the hall.

And they had had their heads together at least twice since they had gotten back to the suite. Cajeiri noted that fact. He had very good ears—too good, Great-grandmother often said– and he knew a good many of the Guild hand-signs he was not supposed to know, because Banichi and Jago had taught him, and so had Antaro and Jegari, whenever they learned them.

There was no sign for our seniors are out of their mindsand there was none for we are superior to all these people. But that was rather well communicated without their saying a thing.

“Luca-ji. Jico-ji,” he said, in the process of shrugging on a light daycoat Jegari held for him. “Are we possibly discussing my great-grandmother’s business?”

That got their attention. Instantly. And he thought, If they lie to me, they will be in trouble.

Lucasi bowed slightly, a little more than a nod. “We were discussing the events in the house, yes, nandi.”

“Do we form policy, nadiin-ji?”

A small silence. A slightly seditious silence. Seditiouswas one of Great-uncle’s words. Conspiratorialwas another.

“We do not,” Lucasi said with a second bow.

Cajeiri wished he had a cane like Great-grandmother’s. It would be very useful with manners like that.

“You are much too smooth,” Cajeiri said. “Smoothness is just a little step from lying.”

“We do not lie, nandi!”

“What is a lie?” he asked back—seguing right to one of Great-grandmother’s little lectures.

“We do not lie.”

“Answer me! What is a lie?”

A deep, annoyed breath. “A falsehood, nandi. And where have we uttered a falsehood?”

“You try to give me a false impression. Thatis a lie. You talk in signs and you discuss my great-grandmother. That is stupid, by itself! And lying to me does not improve it!”

A sullen bow in reply. “If you choose to regard it that way, nandi.”

“Do you see a difference in it, nadiin? Ido not. You may be called upon to lie in my service. But never lie to me. Never lie to Antaro and Jegari. And never conceal your opinions from me! But be verycareful of my great-grandmother!”

They both looked as if they had a mouthful of something very unpleasant.

“Well?” he said. “Say it.”

“We are concerned,” Veijico said. “We are greatly concerned that your elders are making dangerous decisions. Your great-grandmother is aiji-dowager, but she is notthe aiji. We are bound to report to him.”

“And I say you do not! Who do you think you are, nadiin? Higher than Cenedi? Higher than Banichi?”

“We report to the aiji, your father!”

“Regarding me! Regarding when I break one of nand’ Bren’s rules or get lost on the boat! But you do not make calls to my father about my great-grandmother, or you will be very sorry for it. You do not meddle! Do you hear me?”

“We hear,” Lucasi said in a low voice, and not a shred of remorse was in evidence. “But we have an opinion, nandi.”

“State it.”

“These are foreigners,” Veijico said after a moment of silence, “with their own man’chi.”

“ Whois a foreigner?” he asked. “Do we mean the Edi?” Deeper breath. “Or do we mean nand’ Bren? Or do we mean nand’ Geigi, who comes from the space station?”

Another silence. Then, from Lucasi: “We are concerned about the welfare of this house, nandi. Your great-grandmother is attempting to replace the lord of Maschi clan. This will upset the whole aishidi’tat. It affects every lord. It will not be popular.”

“Maybe,” he said. “But it may be smart, if Pairuti is a fool like Baiji, or if he has made bad bargains with the wrong people.”

“And Lord Geigi and Lord Bren are considering going to the Maschi house! That is stupid, nandi!”

“We doubt it is.”

“ Youare eight years old.”

Oh, thereit was. Antaro and Jegari took in their breath. He saw their heads lift, and saw them both like wound springs, ready to say something. He signed no.

And smiled, just like Great-grandmother. “Yes, I am at an infelicitous age,” he said, not personally using the insulting and unlucky eight. “But I understand when not to touch things. You should learn it.”

Two very rigid faces. “We were put here,” Veijico said, “because we have a mature understanding, which you, young lord, do not yet—”

“ You were put here,” Cajeiri said, “because I make guards look bad and tutors quit. The only ones who can keep up with me are Antaro and Jegari. See if you can, if I get mad at you.”

That got frowns. “We can keep up with you,” Veijico said. “Never doubt that.”

“Good,” he said. “Baji-naji, nadiin. People have been wrong. And you do notcall my father to report on my great-grandmother. Sometimes my great-grandmother is scary. So are her associates. You should get used to this. My father is used to it. So should you be, if you are going to try to keep up with me.”

Sullen silence from Lucasi, and one from Veijico. A scarcely perceptible bow from Lucasi.

“Are you honest with me?” Cajeiri asked. “Do you still think I am stupid and have to be lied to?”

A little pause additional. Then a slow bow from Lucasi and from Veijico, nearly simultaneous. “No,” they said.

Not: No, nandi. Just no. They were saying what they had to say. But he realized something right then that he should have felt much sooner. There was no connection. There was no man’chi. And there was no inclination toward it. They might feel it toward his father. But who knew where else—if it was not to him?

But everybodywho was not his father’s enemy felt man’chi toward his father. To decide that wastheir man’chi—that was more than a little presumptuous on their part. Presumptuous. That was what mani would say. They thought they were in his father’s guard. They found fault with his great-grandmother and practically everybody, including him.

A lot of people in the central clans were like that. But theywere from the mountains. They had made up their minds to be like that.

And he was mad.

He was very mad at them. And they knew it. It was in the stares they gave back, and they were not in the least sorry.

“You know far less than you think you do,” he said. He would neverdare say that to the least of Great-grandmother’s men. He would never dare say that to the maid who cleaned the room. But he said it, and meant it, and glared at them.

He had finally disturbed them. Good.

But they were not sorry about it.

He did not like that. People in one’s guard who were not in one’s man’chi were dangerous people, people he did not want near him.

But his father had given them to him, and he was stuck with them.

He could give them one more day and let everybody cool down, and thencall his father. Or tell mani. They would not last long if he talked to mani, who would talk to Cenedi, who would find someplace to put them, no question.

He was not quite ready to do that. Just upset. And sometimes his upsets went away in an hour.

“You have made me mad,” he said, “and that is stupid, nadiin.”

“Nandi,” Antaro said quietly, “they areGuild. And you did put us over them, and that is hard for them.”

“We do not need defense, nadi,” Veijico said shortly.

“Twice fools!” Cajeiri said, and set his jaw. “Give methat face, nadiin!”

It was what mani would say when hesulked. And it got their attention.

“I could turn you over to mani,” he said. “But I am mad right now. And when you do something involving my great-grandmother you had better mean it. So I am giving you one more chance. You take my orders.”

A deep breath from Veijico. A little backing up, from both of them, as if, finally, they had had better sense, or saw a way out. If you corner somebody—Banichi had told him once, and he had always remembered it—you can make them go where you want, by what escape you give them.

“You go,” he said, “and keep an eye on things in the house, and if anything happens about what we heard today, or if anything changes, or you even suspect it is changing, you come back to me and tell me. But do not follow me about, and do not ever be telling me what to do. You can give me your opinions. But you cannotgive me orders.”

“Nandi,” Veijico said, and finally bowed her head and took a quieter stance. Lucasi did, too.

“Go do that,” he said, fairly satisfied with himself, even if he was still mad.

Only when they had gone and he was alone with Antaro and Jegari, he let go a lengthy breath and let a quieter expression back to his face.

“Do you think they will do it?” he asked them outright.

“One is not sure,” Jegari said. “But you scared them, nandi.”

“Good!” he said. “ Youare senior in my household, nadiin-ji, and will always be, no matter how high they are in the Guild. And for right now, none of the Guild under this roof are happy with them.”

“One has noticed that,” Antaro said.

“But we are obliged to take their orders in Guild matters,” Jegari said, “unless we have orders from you not to.”

“You have, nadiin-ji. We orderyou to refuse any order from them you think is stupid. Or wrong. And we want to know what they said and what they were doing. Their man’chi is notto us!”

“One perceived that, nandi,” Jegari said.

“One perceived it,” Antaro said in a quiet voice, “and was not that sure, until now. One is a little concerned, nandi. We were prepared to be careful what orders we took. At least to go to Cenedi or Banichi.”

Two of his aishid had political sense and discretion. The same two of his aishid had learned from Banichi and Cenedi, and that put them forever ahead of two who had not, in his opinion.

Two of his aishid had a real man’chi to him, and he cared deeply about that. The other two—it might yet come. If he got control of his temper. His father’s temper, Great-grandmother called it, and said she had none.

But he rather hoped it was hers he had, which was just a little quieter.

He had not shouted, had he?

And he thought he had put a little fear into those two. More than a little. He might be infelicitous eight, but he was nearly nine, and he was smarter than almost anybody except the people his father had left in charge of him, which he thought might be why his father had left him here—unless his father was tired of him getting in trouble and wanted to scare him.

Fine, if that was the case. He was only a little scaredc less about what was going on outside the house than about the two Assassins his father had given him to protect him.

His father had given him a problem, was what. A damned big problem. And for the first time he wondered if his father knew howbigc or had these two so wound up in man’chi to himself that he never conceived they could be that much of a problem where he sent them. Maybe they were to be perfect snoops into hisaishid, and into nand’ Bren’s household and into mani’s.

Would his father doa thing like that?

It was what mani said, Watch out for a man whose enemies keep disappearing.

Well, that was his father, damned sure. Most everyone knew his father that way.

But then, one could also say that about Great-grandmother.

Both of them had been watching out for him, all his life. Now he had to look out for himself.

If he could takethe man’chi of two of his father’s guard, that would be something, would it not? He had gone head to head with these two, and scared them.

The question was, did he want them? And could he get them at all, the way he had Jegari and Antaro? Did they have it in them, to be what Jegari and Antaro were?

Mani had told him, when she took him away from the ship and his human associates, that there were important things he had to learn, and things he never would feel in the right way, until he dealt with atevi and lived in the world.

Was this it?

His whole body felt different, hot and not angry, just– overheated, all the way down to his toes. Stupid-hot, like a sugar high, but different. Not bad. Not safe, eitherc like looking down a long, dark tunnel that was not quite scary. It had no exit to either side, and no way back, but he knew he owned it, and he suddenly conceived the notion hewas the danger here. He wondered if he lookeddifferent.

He needed to be apart from Veijico and Lucasi for a few hours, was what. Antaro and Jegari were all right. They steadied him down and they could make him laugh, which was what he very much needed right now. He very, very much needed that.

10

« ^ »

Thus far, probably bored out of their minds, Bren thought, Toby and Barb were dutifully keeping to the basement, through all the coming and going in the house.

He went downstairs into the servants’ domain—Banichi and Jago stayed right with him despite his assurances that everything was calm and they could take a little rest; and they walked with him through the halls, two shadows generally one on a side, except where they passed the occasional servant on business. It was a bit of a warren down here, rooms diced up smaller than those above, and the floor plan much more humanish, having a big square of a central block and a corridor all the way around. The main kitchens were down here, with their back stairs up to the dining room service area; and next to them the laundry and the servant baths all clustered together at a right angle—sharing plumbing.

Beyond that side of the big block, beyond fire-doors and sound-baffling, was the servants’ own recreation hall, their own library and dining room, and beyond that, again another fire-door, the junior servants’ quarters.

Baiji occupied one of these rooms. One of Ilisidi’s young men, on duty at that door, had been reading. He set down his book so fast he dropped it, and got up with a little bow, which Bren returned—though likeliest it was Banichi and Jago whose presence had made him scramble.

“Your guest is not my concern,” Bren said mildly. “One trusts the fellow is busy at his writing. My brother is down here. Where would he be?”

“The third left, nandi.” The young man walked ahead of them, escorting them that far, and knocked on the door for him before retreating and leaving Banichi and Jago in charge.

The door opened. Toby saw him with some relief—stood aside as he entered, and left the door open; but Banichi and Jago opted for the hall, and shut the door, likely to go back and pass the time sociably with Ilisidi’s lonely and very anxious youngest guard.

Barb sat at the little table, where the light was best, doing a little writing herself. The disturbed second chair showed where Toby had likely been sitting before he heard the door and got up. The bed, just beyond the partial arch, was made and neat: the servants would have seen to that; but maybe two ship-dwellers had taken care of it themselves.

“Are we being let out?” Toby asked hopefully.

“Sorry. Not yet.” Bren dropped into the chair by the door and heaved a heavy sigh as Toby sank back into the second chair at the table.

“Ah, well,” Toby said. “Any idea when?”

“Well, it’s stayed quiet out. We haven’t had any further trouble. And Geigi’s talking about going home to his estate—that may provoke something. Likely it will. But ifit does, it may shift the trouble over to Kajiminda—and that may get your upstairs room back.”

“That still throws you short,” Toby said. “If you can get Geigi home, you can at least get us to our boat.”

“Sorry. The bus doesn’t go down the hill. You’re safer here.”

“You can only play so much solitaire,” Barb said, and Toby said nothing, only looked glum.

“You’re exposed to snipers down on the boat,” Bren said. “It makes me nervous, your being there.”

Sighs from both of them. “We can’t go into the garden, I suppose, ” Barb said.

“No,” he said. “But it’s not forever. There’s movement in the situation.”

“What kind of movement?”

“Best not discuss all of it. But things are happening.”

“We’re not pacing the floor yet. We’ve threatened murder of each other if we get to that.”

“The room is bigger than the boat.”

“There’s no deck,” Toby said. “And there’s no window. —I’m not complaining, Bren. Honestly not.”

“You’re complaining,” he said wryly. “And I’m honestly sympathetic. Just not a thing I can do to make it safe out there.”

“We’re just blowing off steam,” Toby said. “Honestly. We aren’t complaining. Being alive is worth a little inconvenience. We’re grateful to be here—grateful to the servants who gave up their room for us. We’re here, we’re dry, we’re not full of holes—”

“I’ll relay that to the fellows who live here,” he said, with a little smile. “But I can at least give you a day pass. Things have quietened enough you’ll be welcome upstairs at most any time. Just don’t wait for directions. Duck down here fast if there’s an alarm of any kind. I’m afraid the library’s off limits now; just too crowded in there. But you can use the sitting room, what time we’re not having other meetings. Staff will signal you. I’ll advise them to tell you that.”

“We’ve become the ghosts in your walls,” Barb laughed. “Spooks in the basement.”

“That’s it,” he said.

“Staff has been really good,” Barb said. “They won’t let us make our own bed. We tried, and the maid had a fit.”

He laughed gently. “The juniors have that job and if they don’t do it, the seniors will be on them. Don’t object.” Which said, he got up to go.

“What?” Toby protested. “You’re not staying for a round of poker? We play for promises.”

“I’m up to my ears in must-dos. I just want you to know there’s some movement in the situation, and so far, so good. We have people watching your boat round the clock. No worries down there.”

“Can we possibly help?” Toby asked. “Can we actually doanything around the place? Can we hammer nails, carry boxes, help with the repair?”

He shook his head. “That’s the downside of having an efficient staff. They have their ways. Just relax. Rest. Take long baths.”

“Can I at least get some coastal charts?”

Those were slightly classified. But he did have them. And Toby was in Tabini’s good graces. He nodded. “I’ll send a batch down.”

Thatbrightened up his two sailors. He felt rather good about that.

So he took his leave, collected Banichi and Jago, and went back upstairs to his office, while Banichi and Jago, secure in the knowledge of exactly where he was, in a fortified room with storm shutters shut, got a little down time of their own.

“Coastal charts,” he recalled. “Toby wanted coastal charts.” He went over to the pigeonhole cabinet, unlocked the case and pulled out several. “Have these run down to him, nadiin-ji. I take responsibility.”

Jago went to do it. Banichi diverted himself to somber consultation with Tano, Algini, and Nawari.

And he sat down with the database again, trying to discover how Pairuti’s bloodline—and Geigi’s—connected to the world at large, over the last three hundred years.

Meticulous research on kinships. Who was related to whom and exactly the sequence of exterior and internal events– negotiations in which certain marriages had been contracted and when they had terminated, and more importantly with what offspring, reared by which half of the arrangement, and with what claims of inheritance. Dry stuff—until you discovered you had a relative poised to lodge a claim or engage an Assassin to remove an obstacle.

One of the interesting tactics of marriage politics was infiltration of another clan: marry someone in, let them arrive with the usual staff. That staff then formed connections with other, local staff—and even once the original marriage had run its course—it left a legacy in that clan that couldbe activated even generations down.

And there the paidhi ran head on into that most curious of atevi emotions: man’chi. Attachment. Affiliation. When it triggered, by whatever triggered it, be it the right pheromones or a sense of obligation or ambition or compatible direction—one ateva bonded to another. When it happened properly, in related clans or within a clan, it was the very mortar of society. When it happened between people from clans that were natural enemies, it could be hell on earth.

There’d been a lot of marrying, for instance, of Marid eligibles out and around their district, begetting little time bombs– people never quite at home in their birth-clan, longing, perhaps, for acceptance; and one could imagine, ultimately finding it– because the Marid clans were not stupid.

So the web grew, decade by decade, and that sort of thing had been going on for a lot of decades all up and down the coast and somewhat inland. Sensibly, a stable person was not going to run amok in the household at the behest of some third cousin down in the Marid. But take a little unscheduled income from that cousin for some apparently meaningless datum? Much easier. If you were a very smart spymaster, you didn’t call on people for big, noisy things or life changes. You got bits and pieces from several sources and never let any single person put two and three pieces together.

If you were a lord like Geigi, who’d actually married into the Marid, or drawn a wife out of there, you sensibly worried about the safety of your household—but that household being Edi, the likelihood of any lingering liaison was not high at all. It had surely frustrated the Marid, and perhaps made them wonder who was spying on whom. Geigi’s ex-wife had not risen high in her life, nothing so grand, after Geigi. She’d gone off to the Marid taking all Geigi’s account numbers with her, but Geigi, Rational Determinist that he was—had not been superstitious. He had immediately changed them, and the Marid’s attempts to get into those accounts had rung alarms through the banking system, a defeat that had greatly embarrassed Machigi’s predecessor.

It had been an elegant, quiet revenge that had done the wife’s whole family no good at all. Doubtless they took it personally.

Paru was the subclan in question, on the ex-wife’s father’s side. He wrote that name down, then got up and walked to the security station, the library, walked in after a polite knock and laid that name on the counter.

Jago, who was nearest, looked at it, and looked up at him curiously.

“This is the clan of Geigi’s wife,” he said, “who was greatly embarrassed in her failure to drain his accounts. And they doown a bank in Separti Township: Fortunate Investments. One simply wonders if they have any current involvement.”

“Paru,” Algini mused. “Fortunate Investments, indeed.”

“Certainly worth inquiring,” Tano said.

“Bren-ji is doing our job, nadiin-ji,” Jago said, amused.

“One does apologize,” he said, though the reception of his little piece of information was beyond cheerful. It clearly delighted his aishid.

“Permission to discuss with Geigi’s staff,” Banichi said.

His bodyguard had a new puzzle. They were cramped in these quarters, they were operating nearly round the clock, and Banichi and Jago had bruises and stitches from the last foray, but they had a puzzle to work on. They were happy.

“I leave it in your hands, nadiin-ji,” he said. “Whatever you deem necessary.”

And they thought his small piece of information was worth tracking. Nobody said, as they usually did, oh, well, they had already investigated that.

So he went back to mining the database with a little more enthusiasm.

When one was put out with half one’s aishid and not speaking to them, it was a grim kind of day. Everybody in nand’ Bren’s house was serious and busy. Cajeiri was bored, bored, bored, and tired of being grown up, which he had been all morning and most of the day, but it was not hisfault half his aishid were obnoxious, and he was tired of dealing with them, so he just found excuses to keep them elsewhere and away from him—it was no cure, but it at least made him happier.

There was a beautiful bay out there, probably sparkling in the sunshine, with boats and everything—but one would never know it, in the house, with all the windows shuttered tight.

There was a garden out there, with sky overhead and things to get into that they had never had time to investigate.

But it was off limits, because there could be snipers.

There was the garden shed, and the wrecked old bus, and all sorts of things worth seeing, not even mentioning there was Najida village not too far away, about which they had only heard, and which they had never yet visited.

And there were fishing boats and the dock and all the shops on down the beach toward the village, from a blacksmith to a net-maker. The servants talked about the net-maker’s son, who was about his age, so he gathered, and it was all off limits, because of snipers and kidnappers. The net-maker’s son could be outside in the sunshine. The aiji’s son was stuck inside, behind shutters.

The Marid was a damned nuisance to him personally, along with all the real harm they had done to completely innocent people, including one of mani’s young men being dead, which was just hard even to think of and terribly sad. When hewas aiji, he was going to be their enemy, and they had better figure how to make peace with him or it would turn out very badly for them.

Probably his father was thinking the same thing, by now, and one was sure Great-grandmother was not going to forgive what the Marid had done, but he wished he knew what his father was doing, and one neverknew entirely what Great-grandmother was going to do, but it could be grim.

It was a scary, worrisome thing, to send Guild out on a mission. Nand’ Bren had had to send Banichi and Jago out, and Jago had gotten hurt, which he was really sorry about. And if things got really bad, they were going to have to send a lot of Guild out, and people he knew could get killed. He hated even thinking about that.