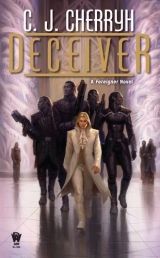

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Refreshment fortunately arrived at that moment. It arrived nicely served on a tray, in fine glasses. And one did not continue a deep discussion, least of all a heated one, past the arrival of any service or the attendance of staff. Geigi heaved a sigh, took the generous glass, and calmed himself with several deep breaths. Bren took his, and quieted his nerves.

“Fresh juice,” Geigi murmured reverently, and lifted his glass and took a very small sip. His eyes shut. “Bliss. Ah, Bren-ji. This is purest liquid bliss. So good. One had forgotten how good.”

Juice reached the station only in frozen concentrate, and not even that, in the priorities of shipment since the coup. It was a traditional welcome in the capital, this early in the day: One had anticipated it would be a treat, and Geigi savored it with a delicate sip and closed his eyes for two sips, and three.

“Ah,” he said. “Ah, Bren-ji. Now I am home.”

“Have you anything else coming in by rail, Geigi-ji?” Bren asked; the road was passing near the train station.

“No,” Geigi said. “Only what we carry. One hesitated to make extravagant demands on the shuttle, coming down, no matter the aiji’s kind indulgence.” A deep sigh. “This may not have been a wise decision, to rely on Kajiminda’s resources—if my fool nephew has plundered the place.”

“Najida stands ready to assist in whatever resupply Kajiminda may lack,” Bren said. “We shall send linens over, food, everything.”

“You are beyond generous. I thank you, I profoundly thank you.” A moment of silence then, and afterward, a refill on the juice. That glass went down. And: “One can bear it, Bren-ji, now that one is fortified. Tellme now. You have told me the exonerating moment. Tell me the very worst you suspect of my nephew. The imagination of Baiji’s misdeeds has quite depressed my appetite. Financial damage. One is certain of it. Harm to my staff. Can there be worse?”

Gentle, plump Geigi had a temper, and a hot one when it finally stirred. And it was very grim, indeed, what he himself suspected. But Geigi asked. One could not lie to him. And delivering the truth, before Geigi could hit the house uninformed, was why he had undertaken this trip out to meet Geigi.

“I do fear worse,” he said.

“Say it,” Geigi said.

“One suspects, Geigi-ji, one suspects—not, indeed, of Baiji, but certainly of his allies—your sister’s decline in health—”

“Gods unfortunate! I knew it!”

“Forgive me, Geigi-ji. This is only my surmise.”

“No, go on, go on, Bren-ji! I want to hear this! I want to hear it all!”

“Her death was too opportune for the Marid. Your sister was astute in most matters. Not so your nephew. Thatmay have drawn them in.”

Geigi heaved a mournful sigh, shaking his head. “She was not in good health. One had not thought. And that boy, that unspeakable boy—”

“Forgive me, nandi, but I rather blame his gullibility.”

“Gullibility and greed together. His mother, in my last calls to her, and hers to me, had been allowing him certain duties, and she claimed he was fulfilling them with some promise. Now one suspects—gods, one suspects—she allowed him some management, and he brought a Marid Assassin under the roof! Murder, Bren-ji! His own mother! Gods above, one does not wish to believe that, even of him!”

“One does not believe he knew,” Bren said. “I think that he was genuinely grieved at your sister’s passing. And very much alone at that point. But he had associates to rush to him and console him and advise himc in those months when communications with the world were cut off.”

During Murini’s administration, when Tabini had been overthrown, and the shuttles had stopped flying, and communication with the space station had stopped.

“We were receiving intelligence relayed up from Mospheira,” Geigi said, “but from the south coast, we had nothing in those days, nothing but reports of unrest and resistence action. He was claiming her post—he was all I had in place. I had no way to intervene.”

“One so regrets it, Geigi-ji.”

“And I so worriedfor that boy’s sake! I sent him letters of advice and encouragement the moment the blackout ended. I actually sent him my understanding this winter when he missed the court session. He must have laughed at that.”

“One thinks, rather, nandi-ji, he grew afraid, and perhaps had the wit to be afraid not only ofyou. Perhaps he grew afraid foryou should you come down to the world and walk into the situation he had created. He fears you to this day. He fears you extremely. He is terrified at the dowager’s apprehension of his crimes; but he is mortally terrified of you. So far as a human can possibly judge, he still does not understand the magnitude of what his allies have done, let alone what they still intend. Mostly, in his eyes, as I suspect—he would still find greater importance in the world by this marriage with the Marid girl. The status of that match would somehow make you respect him. The implication that these people may have assassinated his mother—I did tell him what I suspect—has hit him hard, if a human is any judge of that at all.”

Geigi’s eyes, deep set in, for an ateva, an extraordinarily plump face, were both quick and thoughtful. He pursed his lips and nodded. “You need not deprecate your perception of us, Bren-ji. The paidhi-aiji is notwithout skill in reading us. I can accept he is grieved: she doted on him, all but fed him from her plate as if he were three, and told him every move to make. She greatly exaggerated his accomplishments in her calls to me: I knew that, if nothing else. Now he is alone and unadvised. Consequences he thought he would never see are coming down on his head and his mother is not here to cover his sins. Miss her? Infelicitous gods, of course he misses her!”

A deep, deep breath. “What else do you read in him, paidhi-aiji?”

“That he has to this hour no real apprehension that the world has changed.” He drew a deep breath. “For the Marid’s help in seizing power, Murini did not reward Machigi of the Tasigin. Whatever Murini’s failings, he was never that great a fool. Murini apparently told the Marid to keep their hands off the west coast—I have no proof, but suspect it—and the Marid decided to proceed in their usual way, by stealth, to get their way—they were already moving. Your sister was only their first target. They were plotting to take the whole west coast. I think they had been after that, even before they prompted Murini to seize Shejidan.”

“Building a power base, by doubling the size of their lands, that would almost equal the central and northern clans combined. At that point—they would be as powerful as the aishidi’tat.”

“Murini would not have been able to withstand them once they had that secure,” Bren said, “and if they should succeed now, even with Tabini back in power—they would stillpose an immense threat. Thatis what the aiji-dowager sees, I believe. Tabini-aiji will not quite admit it, but I think he has been playing the Marid, trying to figure what they are up to, where the next strike will come, and has seen every complicated possibility exceptthe rural west coast. And the key to controlling the west coast is—”

“My clan’s treaty with the Edi people.”

“Exactly so. Murini’s supporters—notably the Marid—did notattack my estate during the Troubles, when small coups had taken the mayoralties of little fishing villages clear up in the Isles. Thatis what I find most suspiciousc two large estates, and no move from the Marid against the property of either of us, who were most notably their enemies. The Edi say it was because the Marid was afraid to start a war with them. I think differently. I think the Marid objective was always Kajiminda, for themselves, and they were going after it covertly, against Murini’s orders. When Tabini retook the capital, the Marid suddenly took a very soft approach with Tabini-aiji, claiming they had a revised view of the world—but from what we see here, they kept right on going with their plan. They were going to marry their way into Kajiminda, your nephew was going to fall ill, the Marid wife would run things, and thenthe Marid, behaving ever so nicely in Shejidan, was going to claim Najida through the same inheritance connection with the Maladesi that won them my apartment in the city. Nobody in Shejidan thinks the rural coast is that important. The revenge on me, putting meon the losing side of Bujavid politics, would be particularly pleasant to them—but the fact is, they really do have that distant claim. It is at least arguable. The legislature might insist, to settle the peace for good and all. And there we would be, with the Marid quietly, one step at a time, taking over the west coast, never making a fuss, becoming so, so agreeable and always appearing to be working within the laws. I would be shifted over to some other property the aiji would give me to compensate, probably in another district, and nobodywould be set up to handle the Edi’s interests, except the newly reformed Marid, who are their worst enemies—and does the Ragi center of the country think that a problem? No. Tabini-aiji has had to rebuild the association brick by brick. Everylittle interest has some little claim they want addressed, out of the aiji’s gratitude for their support, of course; but the aishidi’tat is a maze of conflicting claims—an absolute mess, in fact. The Farai claim on the Maladesi inheritance—my properties—is one of a hundred such. How can they be more suspect than any other, after all this upheaval?”

Geigi stared at him, thought it over, and finally heaved an angry sigh. “It makes sense. Gods less fortunate, it makes awful sense, Bren-ji. Have you told all this to the aiji?”

“ Ihave not told the aiji, but my aishid and the dowager’s have surely relayed our suspicions to the aiji’s men.” Information necessarily flowed through protected channels. One did not make pronouncements without proof behind the statement: one hinted, and it was the Guild that investigated such things. “And now you are here. We are so very glad, Geigi-ji.”

“One begins to understand.”

“Here is the concrete proof we have: my aishid has informed me, and the aiji now knows, that the Guild that had operated at Kajiminda were not Maschi. They were from the Marid. Second: there was an assassination in Separti Township. It was unattributed. Baiji claims to know it was Marid agents. The turning point of his understanding, so he said to me, was when he tried to put the first visitors off. He falsely claimed he had a verbal understanding with a young lady south of Separti—and that whole family was assassinated.”

“Gods less fortunate!”

“Indeed. He claims he has constantly found other ways to stall them, claiming he was in mourning for his mother, claiming various things, but the Marid were insistent. You, on the station, were dropping relay stations from space during the Troubles. You were setting up a satellite network to threaten Murini’s regime. You were bringing cell phone technology to Mospheira—it was quite clear that you were trying to encourage someone to take out Murini. So fearing that the tide might turn at any moment and possibly fearing the rumors that Tabini was not dead, the Marid accelerated their demands on your nephew and set up a base in the township before we returned from space. At a certain point, they were going to force that marriage, and your nephew, do him credit, was still stalling even after Tabini-aiji turned up alive. Was still stalling, even this late, when I came to visit. If he had had the courage, he could have gone out on the boat, sailed over to Najida and trusted mystaff to get him safely to Shejidan. But he did not. I admit my affairs are complex—and confusing even to my staff, who did not know where I stood, but—”

“One is absolutely aghast and appalled, Bren-ji.”

“The dowager has promised her support of a house and a lordship for the Edi—you do know that.”

“The dowagerhas made this proposal?”

“One was certain the aiji would have told you.”

“The aiji mentioned there was some local proposal sent up for such a move. I thought it was you!”

“It was the dowager’s proposal and her idea from the beginning. I had no idea she would do it.”

“Well, well. I am not, myself, opposed to it.” Geigi’s face grew sad, the offering of true feelings between old associates, as he dropped any pretense of impassivity. “I have my household on the station. There is my best service to the aishidi’tat, for now and in the foreseeable future. They cannot do without me up there, Bren-ji. Perhaps I shouldcede Kajiminda to the Edi. They would treat it well. Certainly better than my nephew has done. Those things that are Maschi treasures—let them go back to the clan estate at Targai.”

“Wait on that,” Bren said. “Wait, to be sure of your feelings in the matter, honored neighbor; and if I must plead the aiji’s case—preserve the aishidi’tat’s options by holding the treaty as it stands. The relationship between your Maschi clan and the Edi is a great asset in the aishidi’tat. That Kajiminda remain in Maschi hands—is part of that treaty. Building an Edi house, however—this would be my suggestionc supposing, of course, that the aiji does grant this lordship. And I do think he will.”

“The firestorm in the legislature can only be imagined,” Geigi said with a great sigh, and that was the truth. “The inland lords will certainly oppose it. Ragi clan itself will have apoplexies. The Marid—”

“Indeed, the Marid.”

Geigi’s eyes had widened. “They will bolt from the Association. They will declare war. Is this ’Sidi-ji’s desire?”

“It is certainly the likelihood. Things willchange when this becomes public. The relationship the Marid has to the aishidi’tat has given us several wars and a coup, and in my opinion, things mustchange, so that we have no future coup. Perhaps I am too reckless. But the dowager supports this notion, and I am with her on this matter. See what you have walked into, Geigi-ji.”

“Bold. Bold, to say the least.”

“Should you wish to return to the capital—”

“By no means! I wish to be part of this!”

“We will weather the storm,” Bren said. “This region will weather it, and the aishidi’tat will emerge from this, one hopes, with the addition of an ally it can truly trust—the Edi andthe Gan peoples—rather than the South, which has attempted to break up the Association from its outset. So if the five clans of the Marid bolt from the Association, good riddance. That is my view, and the dowager’s, I am convinced. Your support in this matter would speak with a definitive voice—and I personally, would be very much relieved. I value your good opinion, and your judgement, and thisis why I have come out to meet you here, and not in Najida, and to have this talk with you: to tell you what has gone on, and what is being arranged, personally to beg your help—and to give you the opportunity to catch the train back to Shejidan without setting foot in Najida under these circumstances, should that be your choice.”

Geigi looked at him with a directness and emotion rare in his class andhis kind. “One will never forget this gesture, Bren-ji. One will not forget this extraordinary respect.”

“To a greatly valued associate, in a relationship which has stood many, many tests, Geigi-ji. I have the utmost trust in your wisdom and your honesty. Our mutual connections to the aiji and to the aiji-dowager can do a great deal to stabilize this district—at a time when, we both know, in events in the heavens, stability of the aishidi’tat is absolutely critical.”

“There was a time you had great reason to distrust Kajiminda; and there was a time Ihad a Marid wife, and there was a time when I myself trod the outskirts of the aiji’s good will. And yet you have consistently trusted me, Bren-ji. You bewilder me.”

“I have trusted you despite those things. And still do, Geigi-ji.” He added, in Mosphei’, which they had not used: “Humans are crazy like that.”

“Crazy,” Geigi echoed him, “means so many things. Now I am an aging lord, with my estate in disarray. Whyhave you trusted me? You cannot think favors buy favor when clan is involved. You know us far better than that, and you are above all no fool, Bren-ji.”

He smiled. “A few months ago some would have called me a fool to stand by Tabini-aiji. The odds were everywhere against him. I have this most irrational pleasure in your company and this perfectly rational trust in your judgement. You could have declared yourself aiji, in the heavens. And yet you did not, did you, Geigi-ji?”

“I love my comforts too much to be aiji. It is a veryuncomfortable office.”

“You see? You saved the whole aishidi’tat, Geigi-ji. Had Tabini actually been lost—you would have held fast. And that proposition has no doubt.”

“Ha! If I had been put to it, I would have found an aiji and named him.”

“And the world, I have every confidence, would have listened. Your power is inconvenienced, but not at all in ruins. You are held in greatest respect, not alone among atevi.”

“You are very generous, Bren-ji.”

“I am accurate. Why do you suppose the aiji-dowager favors you?”

“Ha!” Geigi laughed outright. “What was between me and ’Sidi-ji certainly does not apply in your case, Bren-ji.”

“Then say we both favor her, and we both know that if we were irrelevant she would not bother with us, and if either one of us merited her disapproval, neither of us would breathe the air. Sheis our ultimate judge, Geigi-ji!”

A laugh, silent, and thoughtful. “ ’Sidi-ji. Yes.” A flicker of the eyes. “There is ’Sidi-ji. If she does not yet call me a fool, then I suppose I may indeed weather this.”

“You shall. One insists on it!”

“She came. With the young lord.”

“The young lord came to visit me. Shecame to see to him. Likewise my brother and his lady, who were visiting when this whole untoward situation presented itself.”

“Shall I see them all, then? I have longed to meet your brother!”

“My brother and Barb-daja will come up to dinner, very likely, which I assure you will be extravagant in your honor. One has given those orders.” He had, in fact, ordered every local delicacy Geigi would have missed all these years. “The actual accommodations I fear are cramped: Najida is a small estate, and my bodyguard now lodges in the library, and my brother and his lady stay on their boat in the harbor.”

“One trusts my nephew is by no means honored with a suite, under such circumstances!”

“Nandi, we have lodged him in a servant’s room in the basement, where there are no windows.”

“Good!” Geigi said, taking a sip of the new drink that had turned up under his hand. “I shall be extremely grateful to stay under your roof tonight, Bren-ji, myself and my staff. We may have no little work to do at Kajiminda, but I am indeed feeling fortified, hearing how things are taken care of.”

“One delights to hear it.”

“The young lord, whom I saw so briefly last year—the boy must be approaching his fortunate birthday.”

“In two months,” Bren said. Nine, following the unnameable eighth, was a very felicitous birthday, and at times they had despaired of Cajeiri ever reaching that happy year. “He has grown in very many ways, Geigi-ji, even in the months since you saw him. He has lately become quite the young gentleman, with encouraging signs of keen judgement.”

5

« ^ »

It would have been far, far more fun to be on the new bus looking out the windows and trying out all the interesting features.

But Great-grandmother had nipped that notion before Cajeiri had even laid his plans.

“Nand’ Bren will deal better with his neighbor without a distraction present. They have distressing matters to discuss.” Great-grandmother meant about Baiji-nadi being locked in the basement and them being shot at and almost killed. He could tell nand’ Geigi a thing or two about that, first-hand.

But probably that would be pert. That was his great-grandmother’s word for it, when he got beyond himself.

So his information was not welcome on the bus.

And there was nothingto do, at present, since they were all locked in the house, nothing that was really interesting, because he could not draw back the slingshota to its full stretch, not without risking ricochets that would hit nand’ Bren’s woodwork, which had already had enough damage from bullets.

So he grew bored with that, and even when he gave turns with the slingshota to his bodyguard, his aishid—they could get no real practice at it in such limited circumstances.

They all wanted to go out into the garden, where they could really let fly—but the doors were kept locked, even when there were village workmen repairing the portico out there (one could hear the hammering all morning.)

He so wanted to be on the bus. But he was forbidden even to meet the bus when it came back. Great-grandmother had thought of that, too, and had forbidden him before he could even think of it. “These two lords have serious business underway, almost certainly. You are not to meet the bus when it arrives. Dignitaries from the village will be arriving to meet Lord Geigi when he gets here and, mind, you are notto enter into an indecorous competition for attention on Lord Bren’s doorstep, young gentleman. You will make yourself politely invisible and do your homework.”

Gruesome. His current homework was court language verbs. Which was not too exciting.

But his father’s visit loomed large in recent memory and it was clear to him he was very lucky to be left here in nand’ Bren’s house, instead of being packed back to Shejidan and his tutor. Sitting in his father’s apartment while his Ajuri clan aunt was visiting and while his Atageini clan great-uncle was living just down the hall—that would be awful. Not to mention that his mother would be upset with him for the mischief he had been in, and if his Ajuri grandfather heard about the train and the boat, through his aunt, he would have his grandfatherfussing about his supervision and demanding more guards, too, possibly even demanding to install some of Ajuriclan with him, which was just too grim to think about. Even if he thought he and his aishid could get the better of anybody Ajuri clan had, it was just too many guards, and more guards just got harder and harder to deal with.

He understood his situation. He understood the threat hanging over him. He had to behave here, and learn his court verbs beyond any mistake, or he would be back in the Bujavid with grown-up guards at every corner.

So after a little while he grew entirely bored with the slingshota and the circumstances they had, and took his aishid back to their suite to think about what they coulddo in the house. Lucasi and Veijico being still new to his service, they were getting used to things, though they really wereGuild, unlike Antaro and Jegari. They were brother and sister like Antaro and Jegari, and everybody older said they were very goodc but.

There was always that butc with Lucasi and Veijico.

The butthat did not let them find out everything they wanted to from senior Guild.

Butc that made Cenedi look grim when he talked about them.

Butc that made Banichi and Jago sigh and talk together in very low voices.

If Lucasi and Veijico had been younger (they were felicitous nineteen and the year after) people would probably call them what they called him: precocious—which was a way of admiring somebody while calling him a pest. Precocious. Pert. Sometimes, even toward him, they were stuck-up; and they were far too inclined to tell Antaro and Jegari they were wrong about something, even about how they sat and how they stood at attention, even when Antaro and Jegari were not allowed to wear a Guild uniform yet. It was just a pest, their know-it-all manner, and it made him mad, but Antaro said, with a sigh, when he mentioned it: “We need to learn, nandi.”

It really was true: having two real Guild in his aishid meant Jegari and Antaro were learning things around the clock now, not just going out for a few hours to the Guild hall. Even he could see a change in how they stood and just the way their eyes tracked—which was probably really good. Jegari and Antaro seemed glad to talk about Guild stuff with Lucasi and Veijico, even if the newcomers weresnotty about it—snotty was one of Gene’s words, up on the ship, or the space station, now, where Gene lived; and it was a good word for those two. Snotty.

And full of themselves. That was another of Gene’s expressions.

The fact was, though, they were smart, they knew they were smart, and they were short of patience with other people, which was going to get them in trouble if they were not just very careful. He was just a year short of nine and hecould see it on the horizonc but not Veijico and Lucasi, oh, no, they were far too smart to take personal criticism from somebody who was infelicitous eight.

Well, heknew they were not smarter than Banichi and Jago and Cenedi, or Tano and Algini—and Cenedi and Algini in particular had no long patience with fools. Algini had been very high up in the Guild before he sort of retired from that job, and one could just see Algini’s eyes looking right at Lucasi’s back in a not-very-good way.

“We did not authorize them to ask!” he had almost blurted out on one occasion, when those two had repeated a request to which Banichi had said no. He had witnessed that second request, and Algini had looked mad. But they were his aishid, and he was responsible for anything they did, so he had only said, later, “You made Algini mad, nadiin-ji.”

“We report to your father, nandi,” Veijico had said quite smoothly and with a shrug. “Not to them.”

“You will not disrespect them!” he had shot back, very sharply, and that had backed them up just a bit. “And if you do it again, nadiin, Ishall report to my father!”

That had set them back for at least an hour.

The thing was, there was a fairly fine dividing line between precocious and foolc he knew that better than most, having crossed that line a few times and having had to hear Great-grandmother tell him where that line was in great detail, interspersed with: “Tell mewhere you made mistakes, boy. Go think!”

Maybe the Guild instructors had told Lucasi and Veijico that exact same thing a few times, too, but Lucasi and Veijico were never going to listen to Guild instructors the way he knew to listen to Great-grandmother—who had used to thump him on the same ear so often he swore it was larger than the other. Great-grandmother probably still made his fatherthink of ear-thumping: she was that fierce.

But clearly the Guild instructors had not set the proper fear in Lucasi and Veijico, and by the way they carried themselves, maybe they had lacked a great-grandmother, up in the high mountains, where they came from.

Maybe, he thought, he should maneuver those two afoul of his great-grandmother and sit back and watch the outcome. That would be interesting. But he was not sure he would ever get them back if they did. So he kept that in reserve.

And thus far he was managing things. At least today Lucasi and Veijico seemed to be showing a little improvement, and being much more polite to everybody all morning. So maybe his threat yesterday had worked. He hated being mad at people. It was like the business with the slingshota. Theywere so sure they would never miss that they thought they could shoot it in the garden hall, never mind the woodwork. Never mind Ramaso would scold them all and hewould get in trouble for it.

And never mind Lucasi had stolen five teacakes from the kitchen this morning, when they had no need to steal at all: Lucasi had rather steal because, he said, it kept him sharp—never mind that some servant might get in trouble for the miscount. It was not Lucasi’s habit, to think of things like that. Great-grandmother would thwack his ear for not thinking about it—if she knew it. But tattling to her was hardly grown-up.

He had a dilemma, was what. He had to make Lucasi and Veijico care.

More, he had to make Lucasi and Veijico care what hethought.

His father was very clever. His father was a great strategist and absolutely ruthless, which was what his father’s enemies said, even though his father was really good to people who deserved his good opinion. His father was so smooth that sometimes people had trouble telling which he was being at the moment—ruthless, or good.

He had thought, a few days ago, that his father had given him two very good guards, despite the suddenness of the surprise; and they were real Guild, and young, and he was going to like them just the way they were and everything was going to be splendid.

Not so easy.

It was like dealing with Great-grandmother. About the time one thought one had her figured out, Great-grandmother proved to be a few moves ahead. Dealing with his father was like that, more than anybody else he had ever met, and he thought about it, sitting in his little sitting-room at his desk, parsing his verbs, and watching Jegari and Antaro over in the corner with Lucasi and Veijico. Jegari and Antaro were listening, all respectful, to something Lucasi and Veijico were telling them—and he thought—

I was stupid when I thought I could ever bring somebody that smart in that fast. I was too nice.

These two are not easy to manage and they come with no ties to me the way Jegari and Antaro have. These two cheat. They lie. They sneak. And that would be all right, except—they disrespect me. They annoy me. One has to be smarter than they are to make them behave themselves, there is nokinship between us, and the fight has to go on all the time—because their man’chi is notto me nor to anybody in the whole midlands– maybe not to anybody up in their mountains, who knows?

It wouldbe easier if I were older. If I could impress them—I could get their man’chi. But they left home to join the Guild. So one supposes man’chi is no longer there. And right now they belong to nobody except maybe the Guild. They say they report to my father, but I doubt they really feel man’chi toward him, or the Guild, or anybody in the world, even their own clan, which is small—too small for theirambitions. One can see that. They have probably always had trouble.

Which was not to say they were bad. Or wrong.