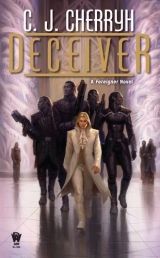

Текст книги "Deceiver "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Then somebody, one of Great-grandmother’s aishid, called out: “Nand’ Toby has been shot! Assistance here!”

12

« ^ »

Bren sighed into soft, cool pillows, next to Jago’s very warm company—after a session of what Jago called good exercise. It was blissful contentment—not without, however, the awareness that very many people were spending the night in somewhat less comfort, on guard around the estate, even on its roof. A little wind had started up, audibly whistling around the eaves, and there had been clouds in the west, good indicator of weather to come before morning.

Bren sighed, rolled over, and rested his head against Jago’s shoulder.

A knock came at the door.

Jago rolled out of bed so fast his head hit the mattress. An atevi knock meant somebody was opening the door, and that didn’t exclude assassins. Jago met the opening door stark naked except for a gun.

The intruder, limned in the dim light from the sitting room, had a Guild-uniform outline. And said, “Excuse me, nandi, but there is trouble at Najida.”

God. That was Tano. Bren bailed out of bed in no different condition than Jago and grabbed a robe. “What trouble, Tano-ji?”

“An attack, nandi. Your brother is injured, and Barb-daja is missing.”

His heart went leaden. “Did they get into the house?”

“No, nandi. They were outside. They were driven off.”

“How badly is my brother hurt?”

“Seriously, nandi, not fatally, is the report. They are bringing him to the house. The dowager’s physician is standing by.” Tano’s voice trailed off slightly as he pressed a hand to his ear. “There is a phone call from the house. Ramaso is reporting. The house is secure.”

Toby. God. Toby wasn’t his first duty. “The dowager,” he asked. “Cajeiri.”

“—was thought to be outside, nandi, but turned up in the house. Lucasi and Veijico, however, are failing to report.”

“Damn!” he said, and raked a hand through his hair. Complicitous? Tabini-aiji himself had assigned those two—they could notbe working for the Marid. Tabini’s organization could notbe that compromised.

And Tobyc

They could need blood at Najida. Human blood. Barb was missing. He was the only human on this side of the strait. “I have to go there,” he said. “I am Toby’s blood type. I have to get there as soon as possible.”

Jago nodded, once, affirmatively. “Yes,” she said, with no argument. And to Tano: “Wake Banichi. Safest we allgo back, nandi. We must wake Lord Geigi.”

All their plans were thrown upside down. It would look like retreat, which had its own impact on the situation for the whole region. But they had no choice.

Banichi had shown up before Tano even cleared the room. Four or five handsigns flew between them, and Banichi said, “I shall wake Lord Geigi. Haste is paramount. Packing can wait.” Two more handsigns and Banichi was gone.

“Algini will negotiate this with the locals,” Jago said, “and with the Guild. Dress, Bren-ji.”

Dress. Fast. He couldn’tgo over the emotional edge. He had Guild under his direction: he had Geigi’s plan for the situation left exposed and fragile. He couldn’t put them at risk by flying about in a mental fog. He had his professionals opposing other professionals who were intending to do all the damage they could, and he had to get his thoughts in order.

Getting that bus back down that road in the dark was not going to be safe. But they’d made a mistake coming back here earlier than they’d expected, relying on the Edi irregulars to hold back Guild professionals—political decision in a military situation, which was stillright, politically, but potentially, now, they had exposed a second target, depending on how many resources the Marid had left on the coastc and how far Tabini’s men had retreated.

They’d expected the strike to come at Kajiminda.

But Barb missing—and Cajeiri’s two new bodyguards with her—

God, that was damned suspicious, no matter Tabini had appointed them; and he hoped that Algini, who had major clout with the Guild, and Banichi, who had major ins with Tabini, could give them some information.

Which didn’t make damned sense. If they were infiltrators, why in hell go after Barb, and not the aiji-dowager, for God’s sake? Why not Cajeiri?

No, it sounded more like Cajeiri’s two guards were themselves in trouble. And if that was the case, either the enemy had been very lucky, or Najida was facing somebody very, very good, and thatdidn’t augur well for the safety of anybody, here or there.

He threw on his rougher clothes, sturdy coat, minimum of lace, and he put the gun in his pocket. More, over the lot, he put on Jago’s spare jacket—it was far shorter than his coat, and still weighed like lead, but he felt safer with that on, undignified as it looked. Jago ducked into the bedroom, helped him zip the jacket, grabbed up her own gear, and had him out into the front hall before Geigi and his majordomo arrived.

“An outrageous situation,” was Geigi’s word for what had happened. “One is devastated, Bren-ji, devastated at the attack on your household.” And to his majordomo: “We must support our neighbors, Bara-ji. My bodyguard will stay here with half of nand’ Bren’s guard to defend this house and my staff. We are calling in support from Najida and the township, and we are going with nand’ Bren in the care of his bodyguard, as quickly as we can, to bring nand’ Bren to his brother-of-both-parents. One asks, one asks fervently, Bara-ji, that you keep close, trust to your defense, and hold the house safe. Do not attempt to defend the grounds! Reinforcements are coming from the capital in a matter of hours. We are assured of it.”

Tabini knew what had happened, then. It was word he had not had, but expected.

And Tano and Algini were electing to stay at Kajiminda? It was a Guild decision. He didn’t meddle.

“Yes,” the old man said, bowing. “No one of ill intent will cross this threshold, nandi.”

Outside there was the sound of the bus engine, as it pulled up to the front door. Banichi and Jago were there, household servants had a small amount of gear, and there was no time for more farewells or expression of sentiment. They moved forward, the small party they had assembled. The majordomo opened one house door, and as it opened, Jago flung an arm around Bren, and hurried him for the bus door—which this time faced the house door at very short range. He scrambled up the tall steps at all the speed he could muster, Geigi boarded with Banichi, and Jago herself took over the driver’s seat while the assigned driver, a Najida man, took the seat behind.

The door shut. They rolled. Immediately. The bus whipped around the U of the drive, gathering speed as they headed down the long estate grounds road for the gate.

Bren didn’t ask whether he should be on the floor. Banichi had set Geigi on the floor in the stairwell, ordered their erstwhile driver to the floorboards and crouched on the floor beside Jago, holding on to the rail with one arm and keeping a heavy rifle tucked in the other while the bus roared along the road.

They slewed around what had to be the turn onto the main road and Jago opened it up for all it was worth, no matter the condition of the road.

“We are not using the bridge,” she warned them. “Hold on!”

God, Bren thought. He knew why not. The little bridge was a prime candidate for sabotage—but he wasn’t sure the bus could make it across the intermittent stream below.

It did. It scraped, but Jago shifted and spun the wheel, and they bounced, but they cleared it and kept going, breaking brush and throwing rock as they rejoined the road and opened up wide.

Banichi said one word into his com. That was all Bren saw of communications between their bus and anywhere else, but at very least Najida’s defenders were not going to mistake the bus for any other vehicle—even the irregulars couldn’t make that mistake.

Nor could their enemies, unfortunately. Bren maintained a death grip on the seat stanchion nearest, tried to keep his foot from contacting Geigi, who was having as difficult a time maintaining his place against the door.

It was no short trip. And they were going where they knewthe trouble was. Guild tactics were rarely those of pitched battle; but they were making racket enough it was likely to make their attackers think, one hoped, that they were coming back in full force, maybe with reinforcements, and leaving Kajiminda open.

It would not make it easier on Kajiminda’s defenders—but it would take their enemy time to change targets, overland. Few forces, but stealthy, preferring ambush if they could—that was Guild. And thus far the bus had met nothing to oppose them. Jago was risking herself, driving, but it was driving of a kind their village driver wouldn’t—probably couldn’t handle.

Jago slacked speed in a series of fast moves, took the bus around the turn onto the east-west road, the one from the train station, slewed it straight, and gathered top speed, just about as much as they could handle on the downhill.

“One thought the shuttle quite the worst,” Geigi muttered, from over his arm. “One is impressed with your bodyguard’s driving, Bren-ji. Quite impressed.”

They slowed again. This time it was the estate drive, and Jago made the corner without sending them into the culvert. They’d made it.

Shots raked the front windows on the driver’s side. Jago ducked and a dozen pocks erupted across the glass.

A fusillade of shots came from the other side, and Jago, upright in the seat and spinning the wheel with all her might in Bren’s upside-down view, pulled them into the yellow glare of the porch lights.

“Douse the porch lights,” Banichi snapped into his com, vexed. And nearly simultaneously shot to his knees and hit the door mechanism, sending it open onto the porch.

They had to move. Bren scrambled up to his knees, shoved at Geigi’s bulk to help him get rightwise around on the steps of the short stairwell, and helped steady him on the way down as armed Guild showed up to assist from outside. He thought he was going to descend the steps next. Banichi simply snatched him by the jacket and hauled him down—set him on his feet on the cobbles and shoved him toward the door.

Jago had to be all right. Bren couldn’t see her, but she had gotten them in—they had bulletproof glass in front. He hadn’t known they had. Thank God, he thought. Thank whoever did the details on the bus—

Banichi shoved him ahead. He was right with Geigi in passing the doors, past a small knot of the dowager’s men, all armed with rifles, and, Banichi letting him go, he turned half about to see Jago and their driver both inbound.

The door shut. Bars went into place.

“The dowager,” he asked on the next breath. “The young gentleman.”

“Safe, nandi,” Nawari said, “Toby-nandi is resting in the dowager’s suite. Siegi-nandi is attending him.”

That was the dowager’s physician. And in Ilisidi’s rooms. He heard with immense relief that Toby was alive—in what condition was not yet apparent, but alive. He began to shed the heavy jacket, and two of the staff assisted.

“Barb-daja?”

“We have not found her,” Nawari said. “Toby-nandi says she ran up the walk. She did not arrive at the top of the hill. Local folk are attempting to track her, but thus far have no indication of her whereabouts. And the two of the young gentleman’s bodyguard are still missing. They may be trying to track the attackers. We are devastated, nandi.”

“You have done everything possible,” he answered. Damned sure the house was upset. But he was not assigning blame at the moment. He looked back at Banichi and Jago, who were debriefing two of Cenedi’s men—Cenedi personally attending the dowager, he was sure—and saw that Jago had blood running down her cheek, a chip off the windshield, almost certainly.

That made him mad. His brother’s being injured made him mad. Whatever decision had sent his people out of safety and on to the hill in the dark made him mad, and at the moment there was nothing he could do about it, except see to Geigi’s comfort as best he could and attend to his brother.

Ramaso had come, standing quietly by the side of the Guild, waiting for instruction.

“Please arrange everything available, Rama-ji, to accommodate Lord Geigi, whatever you must do.”

“Your brother will have more need of the room than I shall, Bren-ji,” Geigi said. “And I brought neither staff nor bodyguard with me. Please let me not discommode him. I should rather share quarters downstairs with my nephew.”

“Then take my suite, nandi. I shall not need it tonight. Ease my mind by accepting.” He stifled a gasp as the heavy jacket at last slid free. “Now I must go to my brother.”

Resting, Nawari had said, with the physician still in attendance. Bren swallowed hard as Ramaso knocked for him, and opened the door on the dowager’s sitting room.

It was not a pretty sight: they had appropriated a buffet and a side table for surgery, and Toby was unconscious, looking pale under the light the physician’s attendants held aloft.

With an upward glance the physician saw him.

“I am his blood type, nandi,” Bren said.

“Good.” The physician, nand’ Siegi, gave a jerk of his elbow, and said, to an attending servant: “Chair.”

A servant helped him with his coat and his shirt sleeve. He sat down, and nand’ Siegi’s assistant arranged the equipment, found a vein—he ignored the procedure except to follow instructions and to try to quiet the pulse that had hammered in his skull ever since he had heard the news. On the table, Toby looked like wax, very, very still—sedated, one hoped.

Didn’t need to be shooting Toby all this adrenaline, he said to himself. Calm down. They were linked now. Direct transfusion. It wasn’t optimum, he guessed, but it was what they had. It was at least doing something—when there was, otherwise, damned little he could do.

At some point, Ilisidi put in an appearance. He was at disadvantage, far from able to stand up, and a little light-headed. He just stayed still and listened.

“We are doing well, aiji-ma,” he heard the physician say to her. “His vital signs are improving. The transfusion will be helpful.”

That was good then. He relaxed over the next while, except for the persistent paths his brain took about Guild business, the security of the house, and of Kajiminda.

And the dowager came back a second time, this time with Cajeiri, who looked at him and at Toby gravely and with very large eyes.

“One is exceedingly sorry, nand’ paidhi,” Cajeiri said.

“You were not outside, were you, young gentleman?”

“I was downstairs. I was quarreling with my bodyguard all day. They were not paying attention, so I left them to teach them a lesson. Everybody thought I had gone outside and down to the boats. And nand’ Toby and Barb-daja went with them to help find me, but they could not understand well enoughc”

“That is enough,” the dowager said. “The paidhi-aiji has other things on his mind. You will rest, nand’ paidhi!” Stamp went the cane. “Sweet tea for the paidhi! What are you standing there expecting? You, young gentleman, may go to your rooms. See you stay there! It is an indecent hour of the night!”

There was motion. In short order there was sweetened tea. He drank it down, and shut his eyes and listened to nand’ Siegi talking to his assistant. The dowager was safe. Cajeiri was. Nobody had gotten into the house, and if anything were going on, he thought his bodyguard would surely come in to advise him.

In time, nand’ Siegi pronounced himself satisfied, and turned his attention to Bren.

“Take more tea, a little nourishment. Rest a few hours, nand’ paidhi. Nand’ Toby is doing well, much assisted by your effort.”

“One is very grateful, nand’ physician. One is extremely grateful. How will nand’ Toby be?”

“He has been fortunate—fortunate to have had medical assistance at hand; fortunate in your arriving. We have repaired the damage. One foresees a good recovery. Tell him he should not exert, should not lift, and he will have no impairment. He should rest. My assistant will remain with him until he wakes. If you wish to stay with him to rest, that would not be amiss. He is greatly concerned for the lady.”

“One understands,” Bren said, and started to get up to bow, but Siegi prevented him with a gesture.

“Stay seated. Rest, nandi. If you wish to walk, use caution.”

“Yes,” he said. It was all there was to say, except, “My profound thanks, nandi.”

So all there was to do was sit there, wondering. Siegi left. The assistant sat beside the light, and Toby rested very quietly.

A servant came, offering more tea, which he declined.

His eyes grew heavy, though his mind continued to race. Then Cenedi came in, quietly, and went into the interior rooms to speak with the dowager, doubtless to report. Bren wanted desperately to know what was going on.

And in a little time Cenedi came out to the sitting room.

“There is no sign of the lady, nand’ paidhi,” Cenedi said. “Two of my men have been attempting to find a clear trail, which is greatly obscured by the passage of the young gentleman’s guard.”

Both hopeful—and grim. “How do you read those two, Cenedi-ji?” he asked.

“We cannot read them,” Cenedisaid, “except in their man’chi, which is considerably in question. The aiji’s men are investigating. These two were often in the operations center. We are not pleased, nandi, with that combination of circumstances.”

Things were in an absolute mess. If there was now question about the loyalty of the two young Guild, there was no knowing how much those two could have overheard, with application of effort—and Cenedi, one could read between the lines, was beyond angry at the situation.

“I shall consult with Banichi, Cenedi-ji. One believes we must make some decisions this morning, and make them quickly.”

“If we had the mecheiti we could find them,” the dowager said grimly. She had arrived silently in the doorway, having gotten no more sleep than he had. “You should have a stable of your own, nand’ paidhi. Someone in this benighted region should have a stable.”

“One wishes we did, aiji-ma,” he said, and stood up, gingerly, fully awake now, and only a little light-headed. It was true. Mecheiti could have tracked them. But the nearest were up in Taiben, near the capital, and bringing them in would take a day at least. “We can send to Taiben,” he said, “but one fears delay under these circumstances.”

“Speed is of the essence,” Ilisidi said grimly, and lowered her voice as Toby stirred, responding to the voices. “Lay plans, paidhi-aiji. Talk to your aishid and talk to Lord Geigi. We mustnot only react to their moves.”

“Yes,” he said. Press them back, the dowager meant. And move to get firm control of the region beforethey could receive any ransom demands—even if it meant Geigi taking control of the Maschi clan. Damned sure it was not a time for retreating and waiting with hands folded for their enemy to dictate the next move—he agreed with that agenda.

Moving into questionable territory to do it—that wasn’t so attractive, but the dowager was absolutely right. They could not back up and wait.

“I shall speak to Lord Geigi,” he said, and went outside, where Banichi was talking to Ramaso and gathered him up, Banichi with a finger to his ear and likely in touch with operations, bringing himself current with what Cenedi might have relayed to ops. “We may need to draw in Tano and Algini, Banichi-ji. We are going forward with our own agenda. Immediately.”

“Yes,” Banichi said. “They will not likely have killed Barb-daja. They would be fools.”

“They will have to find someone who can speak to her,” he said. “And then she knows very little of interest to them. Her main value is in exchange.” When he had started his career he had been practically the only bilingual individual on the continent. That had changed—partly, he was grimly aware, because of hiswork. He’d built the dictionary. He’d taken it from a carefully prescribed permitted word-list to a self-proliferating, auto-cross-referencing file that had gotten wider and wider circulation and contribution.

And with the atevi working on station and the station’s communicating with the planet, and Mospheira’s development of contacts on the continent just during the two years of the Troubles—one couldn’t rely any longer on there notbeing someone who could interrogate a human prisoner.

He couldn’t stay here with Toby while that happened. That wasn’twhere he was needed. Not even the search for Barb preempted the need to get onto the offensive and make their enemy reassess Barb’s value, if they for a moment doubted it.

And if Geigi was going to make the move they needed him to make, Geigi needed support—undeniably official support– not just a solo operation. And to stay alive where they planned to put him, Geigi needed Guild resources familiar with current onworld tech.

The dowager shouldn’t do it. But somebody official had to go with him.

It was a very, very short list of official people available to back Geigi up.

He knocked on Geigi’s door—his own, as happened—and walked into a night-dimmed suite. “One will rouse him, Bren-ji,” Banichi said, and Bren, finding himself a bit light-headed, subsided into his own favorite sitting-room chair.

In short order, Geigi came out, his considerable self wrapped in the bedspread in lieu of a night robe.

“Banichi says your brother is recovering, Bren-ji. This is excellent news.”

“One is greatly relieved. But impossible for me to stay here with him, Geigi-ji. The dowager urges us not to let our enemy seize the initiative. You and I—must continue—”

“Say no more! I am willing, Bren-ji. Outrageous goings-on, and not a shred of help from Maschi clan in our situation! I have lain awake thinking about it. I have thought about my sister, and my nephew, and the situation all across this coast. If I had been here, I would have been outraged. One cannot but help but feel a certain responsibility, as lord of this province—”

“No part of it, Geigi-ji, no part of it attaches to you. You gave your orders, which I well know, and if Maschi clan had followed them, the situation would not be the mess it is! Maschi clan did not maintain ties with the Edi during the Troubles. They did not oversee the transition of power in Kajiminda—everyone on this coast knows that much. Nobody in the north will fault you for taking action. And the aiji and the aiji-dowager will explain it to the rest of the aishidi’tat.”

“One regrets it, still,” Geigi said. “Gods know I did not want this. I did everything conceivable to avoid it. But unless Pairuti proves a better man than he has proved thus far, I shall take the lordship from him. Gods witness Maschi clan did not wantthe clan lordship tied to Kajiminda! Not from the beginning!”

“Times have changed, Geigi-ji. Many things have changed. Wehave changed. And if the nation we met in space comes calling—we musthave our house in order, Geigi-ji. We must. They have formed an impression of us as rational and stable people, with whom a treaty could be lasting. They are strange folk and accustomed to destroy what threatens them. Those of us who were on that voyage have not told all our experience of these people, not to anyone on earth but to Tabini-aijic and for good reason, Geigi-ji. We have no wish to see every lunatic in the aishidi’tat break out in proclaiming they were right, that we have put holes in the sky and people from the moon have taken offense. We dare not meet them with the attitudes of a past age, Geigi-ji, and if it means that you must take steps—one regrets, one regrets extremely the necessity. But this coast, this whole coast is locked in a pattern with the South that originated with the landing of my people on this world. Nothing has changed. Attitudes have not changed. The Marid still thinks domination of this coast is their way to rip the aishidi’tat apart and settle the world as they want it. Theseare your reasons, Geigi-ji. We are fighting against people who believe the space shuttle puts holes in the sky, and who believe they can go on fighting regional wars and profit from them. We know better. And we have to do something.”

“I am with you,” Geigi said. “If I have to appoint a proxy in the heavens, this has to be dealt with. I see that. You could not have convinced me until I saw this stupid attack, Bren-ji, this abysmally stupid action, and not even yet has a single messenger or even an inquiring phone call arrived from Maschi clan! When shall we go, Bren-ji? And most of all—with what resources?”

13

« ^ »

They moved Toby to his own suite and out of the dowager’s at the very crack of dawn. Nand’ Siegi said he was doing well enough, and that was a relief. Servants hurried about, arranging this and that, about which Toby knew nothing.

Bren watched, standing in the hall, judging that things would go more smoothly if he stayed out from underfoot.

And there was one other early watcher in the hall, a forlorn boy, escorted by his two remaining bodyguards. Cajeiri could be stone-faced—his grandmother’s teaching—but at the moment he was not. He looked very lost, very miserable, very short of sleep.

And for once, the disaster was not his fault.

Bren walked over to him, with Banichi attending, and Cajeiri bowed and looked at him about on a level—they were almost the same stature—and bowed a second time.

“One is extremely sorry, nand’ Bren. One is so extremely sorry!”

“One by no means blames you, young gentleman. Your bodyguards behaved badly. Not you.”

“We failed to manage them,” Cajeiri said.

“That would have been difficult,” Bren said, “where the Guild failed. No one blames you.”

“But everything is a mess, nandi! And if I had not gone downstairs, and if I had not evaded my guard—”

Bren shrugged. “Yet rather than consult with those guarding the estate, not to mention those who know you better, those two made a general and undisciplined rush to the boats and drew my brother with them. One may imagine my brother understood that one word and your name, young gentleman, if nothing else. Hence he went with them. And Barb-daja went with my brother. It was your guard’s foolish decision that took them outside.”

“Or perhaps a most ill-timed independence of action,” Banichi said. “And one does not discount that possibility, young gentleman.”

Cajeiri looked at him, confused.

“One does not believe,” Banichi said quietly, “that your bodyguards were acting against you, young gentleman, or they could have done so at any time—against you, or nand’ Bren, or your great-grandmother. I do not believe that motivated them. But Guild man’chi does not rush off into forbidden territory, taking innocent parties with them.”

Confusion became consternation. “You are saying that they werec”

“One does not know what they were doing. But they were not acting in your interest, nandi. If they were acting in your interest, they would not have lost track of you at any moment. If they were acting in your father’s interest, they would not have lost track of you.”

One had to remember the boy had spent two formative years with humans as his closest associates. The instinct for man’chi was potentially disturbed in him. It was one of the concerns everybody had had. If Cajeiri missed fine points—it was only what they were trying to correct.

But two near-adult Guild were a separate issue. When Guild attached—they attached. By what Banichi was saying– attachment had never happened in those two. Regarding Cajeiri, a minor child, that was clear. But if they were working at cross-purposes with the household the aiji himself had assigned them toc that was potentially a far darker matter.

And yet, Banichi had also said they were notacting againstCajeiri—or his father.

“Banichi?” Bren asked, suddenly aware hedidn’t understand what Banichi was reading in them, either, wasn’t wired to understand it—not the way Banichi picked up the clues.

“They were not focused on the young gentleman,” Banichi said. “They have not beenfocused on the young gentleman. They did not regard the young gentleman’s orders, or his anger. Or the aiji’s. This has been the difficulty.”

“Yes!” Jegari said suddenly, as if something had suddenly said the thought in his mind. And far more quietly, Antaro, under her breath: “Yes.”

“Did you know this?” Bren asked, looking at Banichi, shocked if this should be the case.

“One knew they were not attached,” Banichi said, “but not that they would never becomeattached, nandi. That was not evident until this incident. That they wished to be attached was evident, but wishing does not create a man’chi that does not exist.”

So something had tipped across a line for Banichi in that incident. Cajeiri hadn’t picked up on it. Jegari hadn’t been sure, Antaro looked still a little doubtful, but Banichi was willing to say so, now, for some reason which didn’t have clear shape to human senses.

“Explain,” he said, and used the request-form, not the order-form. “Explain, please, Banichi-ji. What is going through their heads? What are they up to?”

A slight shrug. “Their interests are not the young gentleman’s. They have reserved themselves. Now they have acted along those lines without consulting senior Guild in this house. The direction is not clear, but it is not in line with service to the young gentleman. They have laid their lives on this choice.”

“Literally?”

“Literally,” Banichi said grimly, and added a phrase from the machimi: hoishia-an kuonatei—a shooting star. Somebody flaring off. Sometimes it was gallant, admirable. And sometimes it was not. Often enough, in either case, it was fatal.

And it was one of those aspects of the machimi plays that never hadmade rational sense. His personal translation for it had been somewhere between suicide and irrational, emotionally driven sabotage.

“ Why?” he asked. “Do you think they actually askedToby to follow them into that mess, Banichi-ji?”

“Maybe they did,” Banichi said.

“Was it aimed against me?”

Banichi frowned. “One hesitates to guess that, nandi.”

The Guild did not guess. In public. He had to content himself with that, until he could get Banichi in private. But then Banichi said, in a low voice: “The young gentleman is involved, nandi. One surmises, surmises, understand, that while this household may seem ordinary to your staff—it seems vastly different to outsiders. —Is that so, Antaro?”