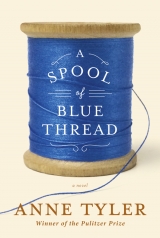

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“The next-door people are back,” Jeannie called, stepping in from the screen porch.

Next door was almost the only house as unassuming as theirs was, and the people she was referring to had been renting it for at least as long as the Whitshanks had been renting theirs. Oddly enough, though, the two families never socialized. They smiled at each other if they happened to be out on the beach at the same time, but they didn’t speak. And although Abby had once or twice debated inviting them over for drinks, Red always voted her down. Leave things as they were, he told her: less chance of any unwelcome intrusions in the future. Even Amanda and Jeannie, on the lookout during the early days for playmates, had hung back shyly, because the next-door people’s two daughters always brought friends of their own, and besides, they were slightly older.

So for all these years – thirty-six, now – the Whitshanks had watched from a distance while the slender young parents next door grew thicker through the middle and their hair turned gray, and their daughters changed from children to young women. One summer in the late nineties, when the daughters were still in their teens, it was noticed that the father of the family never once went down to the water, spending the week instead lying under a blanket in a chaise longue on their deck, and the summer after that, he was no longer with them. A muted, sad little group the next-door people had been that year, when always before they had seemed to enjoy themselves so; but they did come, and they continued to come, the mother taking her early-morning walks along the beach alone now, the daughters in the company of boyfriends who metamorphosed into husbands, by and by, and then a little boy appearing and later a little girl.

“The grandson has brought a friend this year,” Jeannie reported. “Oh, that makes me want to cry.”

“Cry! What for?” Hugh asked her.

“It’s the … circularity, I guess. When we first saw the next-door people the daughters were the ones bringing friends, and now the grandson is, and it starts all over again.”

“You sure have given these folks a lot of thought,” Hugh said.

“Well, they’re us, in a way,” Jeannie said.

But you could see Hugh found that hard to understand.

On the Friday that the Whitshanks arrived, only the men and the children went down to the water. The women were busy unpacking and making beds and organizing supper. But by Saturday, when Amanda and her family showed up, they’d all settled into their routine of a full morning on the beach, and lunch at the house in their sandy swimsuits, and then afternoon on the beach again. The canvas canopy sheltered the white-skinned Whitshank grown-ups, but the in-laws sat brazenly in the sun. Stem’s three little boys challenged the breakers to bowl them over but then ran away at the last minute, shrieking with laughter, while Stem stood guard at the water’s edge with his arms folded. Amanda’s Elise, storky and pale in a tutu-like swimsuit, stayed high and dry on a corner of the blanket underneath the canopy, but Susan and Deb spent most of their time diving through the waves. Susan was fourteen this summer – Elise’s age, but she seemed to have more in common with thirteen-year-old Deb. Both she and Deb were children still, although Deb was a skinny little thing while Susan was more solidly built, waistless and nearly flat-chested but with something almost voluptuous about her full lips and her large brown eyes. The two of them had a bedroom to themselves this year. Elise used to bunk with them rather than in her parents’ cottage, but not any longer. (She’d gotten stuck up, Deb and Susan claimed.) Alexander was mostly on his own as well – too young for the girls and too sedentary for Stem’s boys. Mostly he stayed seated at the water’s edge, letting the surf froth up and then ebb around his soft white legs, except for when his father coaxed him into a game of paddle ball or a ride on a raft.

Elsewhere on the beach, teenagers built giant sand castles, and mothers dipped their babies’ bare feet in the foam, and fathers threw Frisbees to their children. Seagulls screamed overhead, and a little plane flew up and down the coastline, trailing a banner that advertised all-you-can-eat crabs.

Amanda and Amanda’s Hugh didn’t seem to be getting along. Or Amanda wasn’t getting along; Hugh appeared cheerfully unaware. Anything he said to her she answered shortly, and when he invited her to take a walk on the beach, she said, “No, thanks,” and turned the corners of her mouth down as she watched him set off on his own.

Abby, sitting next to Amanda but outside the canopy, under the sun, said, “Oh, poor Hugh! Don’t you think you should go with him?” (She was eternally monitoring her daughters’ marriages.) But Amanda didn’t answer, and Abby gave up and went back to her reading. A stack of trashy magazines had been discovered beneath the TV, no doubt left behind by a previous renter, and they had passed through the hands of her granddaughters and then her daughters and ended up with Abby herself, who was leafing through one now and tsk-ing over the silliness. “All this excitement about could so-and-so be pregnant,” she told her daughters, “and I don’t even know who so-and-so is! I’ve never heard of her.” In her skirted pinkswimsuit, her plump shoulders glistening with suntan lotion and her legs lightly dusted with sand, she looked something like a cupcake. She hadn’t ventured into the water at all so far, and neither had Red. In fact, Red was wearing his work shoes and dark socks. Evidently this was the year when the two of them were declaring themselves to be officially old.

“I remember when I first met him, I thought he was a jerk,” Amanda told Denny. She must have been referring to Hugh. “I had that apartment on Chase Street with a garbage chute at the end of the hall, and I kept finding bags of garbage just sitting on the floor around the chute, not sent down the way they should have been. And poking out of the bag I’d see beer bottles and chili cans, things that should have been put in the recycling bin. It made me furious! So one day I taped a sign to a bag: WHOEVER DID THIS IS A PIG.”

“Oh, Amanda! Honestly,” Abby said, but Amanda didn’t seem to hear her. “I don’t know how he knew it was me,” she told Denny, “but he must have. He knocked on my door and he was holding my sign. ‘Did you write this?’ he said, and I said, ‘I most certainly did.’ Well, he put on this big charm act. Said he was terribly sorry, it wouldn’t happen again, he didn’t know the recycling rules and he hadn’t sent the bag down the chute because it wouldn’t fit, blah blah – as if that were any excuse. But I admit, he won me over. You know what, though? I should have paid attention. There it was, all spelled out for me from the beginning: This is a man who thinks he’s the only person on the planet. How much clearer could it have been?”

“So, now does he recycle?” Denny asked.

“You’re missing the point,” Amanda said. “I’m talking about his nature, the very nature of the man. It’s all about what’s expedient, for him. He’s just arranged to sell the restaurant to someone for next to nothing, for a song, merely because he’s bored and he wants to go into something new. Can you believe it?”

“I thought you approved of the something new,” Denny said. “I thought you said it was brilliant.”

“Oh, I was just being supportive. Besides, it’s not the something new I mind; it’s the way he goes about getting rid of the old. He didn’t even consult me! Just took the very first offer he got, because he wants what he wants when he wants it.”

Abby touched Amanda’s arm. She sent a meaningful glance toward Elise, but Amanda said, “What,” and turned away again. And Elise just then stood up in one long graceful movement and began walking toward the water, as if nothing the grown-ups said could have anything to do with her.

“I didn’t know that was how you met,” Abby said. “That’s kind of like a movie! Like a Rock Hudson – Doris Day movie where they start out hating each other. I thought you met in the elevator or something.”

“The man is impossible,” Amanda said, as if Abby hadn’t spoken.

“You can see why he’d jump at the chance to sell, though,” Denny said. “I don’t guess it’s easy unloading a place that serves nothing but turkey.”

“Well, it’s not married to turkey. It could serve other things. And it’s got tons of equipment, ovens and such, that are worth a lot of money.”

“Oh,” Abby said, “poor Hugh. Men don’t handle failure well at all.”

“Mom. Please. Enough with the ‘poor Hugh.’ ”

“Want to take a walk, Ab?” Red asked suddenly. It wasn’t clear whether he’d been listening to what was being said. Maybe he really did feel like a walk just then. At any rate, he heaved himself to his feet and stepped over to give Abby a hand up. She was still shaking her head as they started off down the beach.

“Now they’ll have a long talk about what a bad wife I am,” Amanda said, watching them go.

“Dad walks so slowly these days,” Jeannie said. “Look at him. He’s so stiff.”

“How does he manage at work?” Denny asked her.

“I don’t notice it so much at work. It’s not as if he does anything physically demanding there anymore.”

They watched their parents meet up with Nora, who was returning from a walk of her own. She exchanged a few words with them and then continued toward Stem and her children, floating ethereally through a group of teenage boys tossing a football at the water’s edge. A black tie-on skirt fluttered and parted over her modest one-piece swimsuit, and her dark hair lifted from her shoulders in the breeze. The teenage boys halted their game to follow her with their eyes, one of them cradling the football under his arm.

“The unwitting femme fatale,” Denny murmured, and Amanda gave a little hiss of amusement.

“Is Elise having any fun?” Jeannie asked Amanda. “It doesn’t seem she’s joining in much this year.”

“I have no idea,” Amanda said. “I’m only her mother.”

“I guess ballet has kind of taken her away from things.”

Amanda didn’t answer. The three of them were silent a moment, their gazes fixed on a nearby toddler in a swim diaper who was pursuing a committee of gulls. The gulls strutted ahead of him at a dignified pace, gradually speeding up although they pretended not to notice him.

“How about Susan?” Jeannie asked Denny. “Is she having a good time?”

“She’s having a great time,” he said. “She really likes coming here. These are the only cousins she’s got.”

“Oh, does Carla not have any siblings?”

“Just an unmarried brother.”

Jeannie and Amanda raised their eyebrows at each other.

“How is Carla these days?” Amanda asked after a moment.

“Fine as far as I know.”

“Do you see much of her?”

“No.”

“Do you see anybody?”

“Do I see anybody?”

“You know what I mean. Any women.”

“Not really,” Denny said. And then, just when it seemed the conversation was finished, he added, “Face it, I’m hardly a catch.”

“Why not?” Jeannie asked.

“Well, I kind of come across as a deadbeat. I mean, it’s not as if I’ve been blazing an impressive career path all these years.”

“Oh, that’s ridiculous. Lots of women would fall for you.”

“No,” Denny said, “when you think about it, things haven’t changed much since the days when parents were trying to marry their daughters off to guys with titles and estates. Women still want to know what you do when they meet you. It’s the first question out of their mouths.”

“So? You’re a teacher! Or a substitute teacher, at least.”

“Right,” Denny said.

A little girl ran past them toward the water – the granddaughter of the next-door people. Reflexively, Denny and his sisters half turned to watch the next-door people threading from their house to the beach, carrying towels and folding chairs and a Styrofoam cooler. They arrived at a spot some twenty feet distant from the Whitshanks. The grown-ups unfolded their chairs and settled in a straight row facing the ocean, while the grandson and his friend went down to where the little girl was bounding into the surf.

“Have we ever found out for sure that they come for just the one week?” Amanda asked. “Maybe they’re here all summer.”

“No,” Jeannie said, “we saw them arrive that time, remember? With their suitcases and their beach equipment.”

“Maybe they stay on, then, after we leave.”

“Well, maybe. I guess they could. But I like to think that they go when we do. They have the same conversation we always have: next year, should they make it two weeks? But by the end of their vacation they say, ‘Oh, one week is enough, really.’ And so they come for the same week year after year, and fifty years from now we’ll be saying”—here Jeannie’s voice changed to an old-lady whine—“ ‘Oh, look, it’s the next-door people, and the grandson’s got a grandson now!’ ”

“They’ve brought their lunch today,” Denny said. “We could check out their menu.”

Jeannie said, “What if we marched over there, right this minute, and introduced ourselves?”

“It would be a disappointment,” Amanda said.

“How come?”

“They would turn out to have some boring name, like Smith or Brown. They’d work in, let’s say, advertising, or computer sales or consulting. Whatever they worked in, it would be a letdown. They’d say, ‘Oh, how nice to meet you; we’ve always wondered about you,’ and then we’d have to give our boring names, and our boring occupations.”

“You really think they wonder about us?”

“Well, of course they do.”

“You think they like us?”

“How could they not?” Amanda asked.

Her tone was jokey, but she wasn’t smiling. She was openly studying the next-door people with a serious, searching expression, as if she weren’t so sure after all. Did they find the Whitshanks attractive? Intriguing? Did they admire their large numbers and their closeness? Or had they noticed a hidden crack somewhere – a sharp exchange or an edgy silence or some sign of strain? Oh, what was their opinion? What insights could they reveal, if the Whitshanks walked over to them that very instant and asked?

It was the custom for the men to do the dishes every evening while they were on vacation. They would shoo the women out—“Go on, now! Go! Yes, we know: put the leftovers in the fridge”—and then Denny would fill the sink with hot water and Stem would unfurl a towel. Meanwhile Jeannie’s Hugh, one of those thorough, conscientious types, reorganized the whole kitchen and scrubbed down every surface. Red might carry a few plates in from the dining room, but soon, at the others’ urging, he would settle at the kitchen table with a beer to watch them work.

Amanda’s Hugh wasn’t around for this. Her little family ate most of their suppers in town.

On their final evening, Thursday, the cleanup was more extensive. Every leftover had to be dumped, and the refrigerator shelves had to be emptied and wiped down. Jeannie’s Hugh was in his element. “Throw it out! Yes, that too,” he said when Stem held up a nearly full container of coleslaw. “No point hauling it all the way back to Baltimore.” The three of them slid a glance toward Red, who shared his sister’s horror of waste, but he was thumbing through one of the trashy magazines and he failed to notice.

“What’s the plan for tomorrow?” Denny asked. “We leaving at crack of dawn?”

Hugh said, “Well, I should, at least. I’ve got half a dozen messages on my cell phone.” He meant messages from the college. “Lots of stuff to see to in the dorms.”

“So,” Denny told Stem, “that means fall is coming.”

“Pretty soon,” Stem said. He returned a not-quite-clean plate to the sink.

“You don’t want to wait too long to move back home,” Denny told him, “or the kids will have to switch schools.”

Stem was drying another plate. He stopped for a second, but then he went on drying. “They’ve already switched,” he said. “Nora registered both of the older boys last week.”

“But it makes more sense for you to move back, now that I’m staying on.”

Stem laid the plate on a stack of others.

“You’re not staying,” he said.

“What?”

“You’ll be leaving any time now.”

“What are you talking about?”

Denny had turned to look at him, but Stem went on wiping plates. He said, “You’ll pick a fight with one of us, or you’ll take offense at something. Or one of those calls will come in on your phone from some mysterious acquaintance with some mysterious emergency, and you’ll disappear again.”

“That’s bullshit,” Denny told him.

Jeannie’s Hugh said, “Oh, well now, guys …” and Red looked up from his magazine, one finger marking his place.

“You just say that because you wish I weren’t staying,” Denny told Stem. “I’m well aware you want me out of the way. It’s no surprise to me.”

“I don’t want you out of the way,” Stem said. They were facing each other squarely now. Stem was gripping a plate in one hand and the towel in the other, and he spoke a little more loudly than he needed to. “God! What do I have to do to convince you I’m not out to get you? I don’t want anything that’s yours. I never have! I’m just trying to be a help to Mom and Dad!”

Red said, “What? Wait.”

“Well, isn’t that just like you,” Denny told Stem. “Spilling over with selflessness. Holier than God Almighty.”

Stem started to say something more; he drew in a breath and opened his mouth. Then he made a despairing noise that sounded like “Aarr!” and without even seeming to think about it, he wheeled toward Denny and gave him a violent shove.

It wasn’t an attack, exactly. It was more an act of blind frustration. But Denny was caught off balance. He staggered sideways, dropping the plate he held so that it shattered across the floor, and he tried to right himself but fell anyhow, his head grazing the edge of the table before he landed in a sitting position.

“Oh,” Stem said. “Gosh.”

Red stood up, slack-mouthed, with his magazine dangling from one hand. Hugh was hovering in front of the fridge and saying, “Guys. Hey, guys,” and gripping his washrag in a useless sort of way.

Denny began struggling to his feet. His left temple was bleeding. Stem bent to offer him a hand, but instead of accepting it, Denny lunged at him from a half-standing position and butted Stem in the sternum. Stem buckled and fell backwards, slamming against a cabinet. He sat up again, but he looked groggy, and he raised a hand tentatively to the back of his head.

All at once the kitchen was full of fluttering women and shocked, wide-eyed children. There seemed to be a multitude of them, way more than could be accounted for. Abby was saying, “What is this? What’s happened?” and Nora was leaning over Stem, trying to help him up. “Keep him sitting,” Jeannie told her. “Stem? Do you feel dizzy?” Stem went on holding his head, with an uncertain look on his face. Shards of the plate lay all around him.

Denny stood backed against the sink. He seemed bewildered, more than anything. “I don’t know what came over him!” he said. “He just went from zero to sixty!” Blood was traveling down the side of his face, darkening the olive green of his T-shirt.

“Look at you,” Jeannie told him. “We’ve got to get you to an emergency room. The two of you.”

“I don’t need an emergency room,” Denny said, at the same time that Stem said, “I’m okay. Let me up.”

“They both have to go,” Abby said. “Denny needs stitches and Stem might have a concussion.”

“I’m fine,” Stem and Denny said in chorus.

“Let’s at least put you on the couch,” Nora told Stem. She didn’t seem all that perturbed. She helped him to his feet, this time without Jeannie’s objecting, and guided him out of the room. All the children followed dumbly except for Susan, who was standing very close to Denny and stroking his wrist. Tears were streaming down her cheeks. “What are you crying about?” Denny asked her. “This is nothing. It doesn’t even hurt.” She nodded and swallowed, tears still streaming. Abby put an arm around her and said, “He’s okay, honey. Head wounds always bleed a lot.”

“Out,” Jeannie said. “Everyone out of the kitchen while I check the damage. Get me the first-aid kit, Hugh. It’s in the downstairs bathroom. Susan, I need paper towels.”

Red had sunk back onto his chair at some point, but Abby touched his shoulder and said, “Let’s go to the living room.”

“I don’t understand what happened,” he told her.

“Me neither, but let’s leave Jeannie to take care of things.”

She helped him up, and they moved toward the door. Only Susan remained. She handed Jeannie a roll of paper towels. “Thanks,” Jeannie said. She tore off several sheets and dampened them under the faucet. “First we’re going to clean the wound and see if it needs stitches,” she told Denny. “Sit down.”

“I do not need stitches,” he said. He lowered himself to a chair. She leaned over him and pressed the wad of damp towels to his temple. Susan, meanwhile, sat down in the chair next to his and picked up one of his hands. “Hmm,” Jeannie said. She peered at Denny’s cut. She refolded the paper towels and dabbed again at his temple.

“Ouch,” he said.

“Hugh? Where’s that first-aid kit?”

“Coming right up,” Jeannie’s Hugh said as he entered the kitchen. He handed her what appeared to be a fisherman’s metal tackle box.

Jeannie said, “Go tell the others not to let Stem fall asleep, hear? Leave that,” because Hugh was stooping to pick up shards of the plate. “We need to make sure he doesn’t go into a coma.” She had always been the type who grew authoritative in a crisis. Her long black ponytail almost snapped as she flicked it out of her way.

Hugh left. As soon as he was gone, Denny said, “I swear this was not my fault.”

“Really,” Jeannie said.

“Honest. You’ve got to believe me.”

“Susan, find me the Neosporin.”

Susan raised her eyes to Jeannie’s face but went on sitting there.

“Ointment. In the first-aid kit,” Jeannie told her. She folded the paper towels yet again. They were almost completely red now. Susan let go of Denny’s hand to reach for the kit. Her blouse had a brushstroke of blood smeared across one shoulder.

“We were just doing the dishes,” Denny said, “peaceful as you please. Then Stem flies off the handle because I say he can move home now.”

“Yes, I can just imagine,” Jeannie said.

“What is that supposed to mean?”

She tossed the paper towels into the garbage bin and accepted the Neosporin from Susan. “Hold still,” she told Denny. She applied a dab of ointment. He held still, gazing up at her steadily. She said, “When are you going to drop all this, Denny? Get over it! Give it up!”

“Give what up? He was the one who started it!”

“Don’t you think everyone’s got some kind of … injury? Stem himself, for instance! Couldn’t I feel jealous too, if I put my mind to it? Dad favors Stem way over me, even though I’m a really good worker. He’s always talking about Stem taking charge of the business someday, as if I didn’t exist, as if I couldn’t do every single thing a man can do once somebody shows me how. But guess what, Denny: the fact is that nobody has to show Stem how. He was just, seems like, born knowing how. He can figure things out without being told. He honestly does deserve to be in charge.”

Denny made an impatient snorting noise that she ignored. “Butterfly bandages,” she told Susan. “If you can find me some of those, we’re in business.”

Susan rooted through the first-aid kit, which didn’t seem well organized. She tossed aside scissors, tweezers, rolls of gauze, a bottle of vinegar for jellyfish stings, and came up with a box of butterfly bandages.

“Great,” Jeannie said. She shook several out onto the table, then picked up one and tore open the wrapping. “A few of these should do the trick,” she told Denny. “Hold still, please.”

“It’s not his being in charge I mind,” Denny said. “I sure don’t want to be in charge. It’s that Dad isn’t satisfied with the rest of us. His own three children! You said it yourself: you should be the one taking over the business. You’re a Whitshank. But oh, no, Dad had to go hunting outside the family for someone.”

“He didn’t go hunting,” Jeannie said. She drew back to study the bandage she had applied, and then she reached for another. “He didn’t choose to have Stem join the family. It just happened.”

“All my life, Dad has made me feel I didn’t quite measure up,” Denny said. “Like I’m … lame; I’m lacking. Listen to this, Jeannie: when I was working in Minnesota one summer, I had a boss who thought I had a really good eye. We were putting in cabinets, and I would come up with these design plans that he said were fantastic. He asked if I’d ever considered going into furniture making. He thought I had real talent. Why doesn’t Dad ever feel that way?”

“And then what?” Jeannie asked.

“What do you mean, what?”

“What happened with the furniture making?”

“Oh, well … I forget. I think we moved on to the boring part, then. Baseboards or something. So I quit, by and by.”

Jeannie sighed and collected the bandage wrappings from the table. “Okay, Susan,” she said. “You can help your dad to the living room now.”

But just as Denny was getting to his feet, Stem walked in, with Nora close behind. By the looks of him, he’d recovered from the blow to his head. He seemed himself again, only paler and more rumpled. “Denny,” he said, “I want to apologize.”

“He is very, very sorry,” Nora put in.

“I should not have lost my temper, and I want to pay for your String Cheese Incident T-shirt.”

Denny made a little puffing sound of amusement, and Abby, who had come into the room behind them – of course she had to be part of this, falling all over herself to set her family to rights – said, “Oh, Stem, that’s no problem; I’m sure we can treat it with OxiClean,” which made Denny laugh aloud.

“Forget it,” he told Stem. “Let’s just say it never happened.”

“Well, that’s very generous of you.”

“Fact is, I’m kind of relieved to find out you’re human,” Denny said. “Till now I didn’t think you had a competitive bone in your body.”

“Competitive?”

“Let’s shake on it,” Denny said, holding out his hand.

Stem said, “Why do you say I’m competitive?”

Denny let his hand drop. “Hey,” he said. “You just assaulted me for saying I should be the one to help out with Mom and Dad. You don’t call that competitive?”

“God damn!” Stem said.

Nora said, “Oh! Douglas.”

Stem socked Denny in the mouth.

It wasn’t an expert blow – it landed clumsily, a bit askew – but it was enough to send Denny tumbling back onto his chair. Blood bubbled up instantly from his lower lip. He gave a dazed shake of his head. Abby shrieked, “Stop! Please stop!” and Jeannie said, “Oh, for heaven’s sake,” and Susan started crying again and biting her knuckles. The others appeared in the doorway so instantaneously that it almost seemed they’d been lying in wait for this. Stem was looking surprised. He stared down at his fist, which was scraped across the knuckles. He shifted his gaze to Denny.

“Out,” Jeannie ordered everyone.

Then she said, in a weary tone of voice, “First we’re going to clean the wound and see if it needs stitches.”