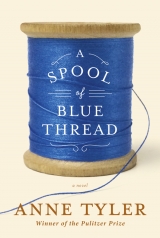

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“He’s acting too meek,” Amanda said. “This is too easy. We need to find out what’s behind it.”

“Yes, you have to wonder why he’s in such a hurry.”

They were talking to each other on their cell phones – Jeannie against a background of electric drills and nail guns, Amanda in the quiet of her office. Shockingly, no one had let them know right away about Red’s announcement. They’d had to hear it the next morning. Stem happened to mention it at work, while he and Jeannie were dealing with a cabinetry issue.

“You did tell him we should talk this over,” Jeannie had said immediately.

“Why would I tell him that?”

“Well, Stem?”

“He’s a grown-up,” Stem said, “and he’s doing what you’ve hoped for all along. Anyhow: whatever he does, Nora and I are leaving.”

“You are?”

“We’re just waiting till her church can find a new home for our tenants.”

“But you never said! You never discussed this with us!”

“Why should I discuss it?” Stem asked. “I’m a grown-up, too.”

Then he rolled up his blueprints and walked out.

“It’s like Stem’s a different person lately,” Jeannie told Amanda on the phone. “He’s almost surly. He was never like this before.”

“It must have to do with Denny,” Amanda said.

“Denny?”

“Denny must have said something to hurt his feelings. You know Denny’s never gotten over Stem moving back home.”

“What could he have said to him, though?”

“What could he have said that he hasn’t already said, is the question. Whatever it was, it must have been a doozie.”

“I don’t believe that,” Jeannie said. “Denny’s been on fairly good behavior lately.”

But as soon as she hung up, she phoned him. (Wasn’t it typical that even now, when he was living on Bouton Road again, she had to call his cell phone if she wanted to talk to him?)

It was past ten in the morning, but he must not have been fully awake yet. He answered in a muffled-sounding voice: “What.”

“Stem says Dad is going to move to an apartment,” Jeannie told him.

“Yeah, seems like he is.”

“Where did that come from?”

“Beats me.”

“And Stem and Nora are just waiting till their tenants find a new place and then they’re leaving too.”

Denny yawned aloud and said, “Well, that makes sense.”

“Did you say anything to him?”

“To Stem?”

“Did you say anything that made him want to leave?”

“Dad’s moving, Jeannie. Why wouldn’t Stem leave?”

“But he was leaving in any case, he said. And he’s been acting so different these days, so grumpy and short-tempered.”

“He has?” Denny said.

“Something’s eating him, I tell you. It sounds like he didn’t even try to talk Dad out of this.”

“Nope. None of us did.”

“You mean you think it’s okay? Dad giving up on the house his own father built?”

“Sure.”

“You’ll be out of a home, you know,” Jeannie said. “We’ll have to sell. I don’t see you affording the taxes on an eight-room house on Bouton Road; you don’t even have a job.”

“Right,” Denny said, not appearing to take offense.

“So will you go back to New Jersey?”

“Most likely.”

Jeannie was quiet a moment.

“I don’t understand you,” she said finally.

“Okay …”

“You live here; you live there; you move around like it doesn’t matter where you live. You don’t seem to have any friends; you don’t have a real profession … Is there anyone you really care about? I’m not counting Susan; our children are just … extensions of our own selves. But do you care how you worried Mom and Dad? Do you care about us? About me? Did you say something hurtful to Stem that’s made him mad at everyone?”

“I never said a word to Stem,” Denny said.

And he hung up.

“I feel awful,” Jeannie told Amanda. They were on the phone again, although this time Amanda had answered in a hurried, impatient tone. “What now?” she had asked, sounding more like Denny than she knew.

“I really let Denny have it,” Jeannie told her. “I accused him of being mean to Stem and giving grief to Mom and Dad and not working and not having any friends.”

“So? What part of that isn’t true?”

“I asked if he even cared about us. Well, specifically me.”

“A reasonable question, I’d say,” Amanda told her.

“I shouldn’t have asked that.”

“Get over it, Jeannie. He deserved every word.”

“But asking if he cared about me, when here he quit his job that time and fell behind on his rent so he could come and help out because I was afraid I was going to smash my baby’s head in!”

There was a silence.

“I didn’t know that,” Amanda said finally.

“You don’t remember that Denny came and stayed with me?”

“I didn’t know you were afraid you’d smash Alexander’s head in.”

“Oh. Well, forget that part.”

“You could have told me that. Or Mom. She was a social worker, for God’s sake!”

“Amanda, forget it. Please.”

There was another silence. Then Amanda said, “But anyhow. The rest of what you said, Denny had coming to him. He was mean to Stem. And he did give Mom and Dad grief; he made their lives a living hell. And he is unemployed, and if he’s got any friends we certainly haven’t met them. And I’m not so sure he cares the least little bit about us! You told me yourself he sounded kind of unhappy when he telephoned that night before he came home. Maybe he was just looking for some excuse to come home.”

“I still feel awful,” Jeannie said.

“Listen, I hate to run, but I’m late for an appointment.”

“Go, then,” Jeannie said, and she stabbed her phone to end the call.

Denny and Nora were in the kitchen, cleaning up after supper. Or Nora was cleaning up, because Denny had done the cooking. But he was still hanging around, picking up random objects here and there on the counter and looking at the bottoms of them and setting them down.

Nora had been talking about Sissy Bailey’s apartment. She had taken Red to see it earlier that afternoon. But he had claimed he could poke a hole in the walls with his index finger, so on Saturday a friend of the family who was a real-estate agent …

Denny said, “Is Stem pissed off about something?”

“Excuse me?” Nora said.

“Jeannie says he’s in a bad mood.”

“Why don’t you ask him?” Nora said. She angled one last saucepan into a tiny space in the dishwasher.

“I thought maybe you could tell me.”

“Is it so hard to just go talk to him? Do you dislike him that much? ”

“I don’t dislike him! Geez.”

Nora closed the dishwasher and turned to look at him. Denny said, “What, you don’t believe me? We get along fine! We’ve always gotten along. I mean, it’s true he can be kind of a goody-goody, like ‘See how much nicer I am than anybody else,’ and he talks in this super-patient way that always sounds so condescending, and legend has it he behaves so well when his life doesn’t work out perfectly although face it, how often has Stem’s life not worked out perfectly? But I have no problem with Stem.”

Nora smiled one of her mysterious smiles.

“Okay,” Denny said. “I’ll just ask him myself.”

“Thanks for making supper,” Nora told him. “It was delicious.”

He raised one arm and let it drop as he walked out.

In the sunroom the evening news was on, but Red was the only one watching. “Where’s Stem?” Denny asked.

“Upstairs with the kids. I think somebody broke something.”

Denny went back out to the hall and climbed the stairs. Children’s voices were tumbling over each other in the bunk room. When he entered, the little boys were snaking that racetrack of theirs across the floor while Stem sat on a lower bunk, studying two parts of a bureau drawer.

“What have we here?” Denny asked him.

“Seems the guys mistook the bureau for a mountain.”

“It was Everest,” Petey told Denny.

“Ah.”

“Could you hand me that glue?” Stem said.

“You really want to use glue on it?”

Stem gave him a look.

Denny passed him the bottle of carpenter’s glue on the bureau. Then he leaned against the door frame, arms folded, one foot cocked across the other. “So,” he said. “Sounds like you’re moving out.”

Stem said, “Yep.” He squirted glue on a section of dovetailing.

“I guess you’re pretty set on it.”

Stem raised his head and glared at Denny. He said, “Don’t even think about telling me I owe him.”

“Huh?”

The little boys glanced up, but then they went back to their racetrack.

“I’ve done my bit,” Stem told Denny. “You stay on yourself, if you think somebody ought to.”

“Did I say that?” Denny asked him. “Why would anybody stay on? Dad’s moving.”

“You know perfectly well he’s just hoping we’ll talk him out of it.”

“I don’t know any such thing,” Denny said. “What is it with you, these days? You’ve been behaving like a brat. Don’t tell me it’s just about Mom.”

“Your mom,” Stem said. He set the glue bottle on the floor. “She wasn’t mine.”

“Well, fine, if you want to put it that way.”

“My mom was B. J. Autry, for your information.”

Denny said, “Oh.”

The little boys went on playing, oblivious. They were staging spectacular wrecks on an overpass.

“And all along, Abby knew that,” Stem said. “She knew and she didn’t tell me. She didn’t even tell Dad.”

“I still don’t see why you’re going around in a snit.”

“I’m in a snit, as you call it, because—”

Stem broke off and stared at him.

“You knew, too,” he said.

“Hmm?”

“This doesn’t surprise you a bit, does it? I should have guessed! All that snooping you used to do: of course! You’ve known for years!”

Denny shrugged. He said, “It’s immaterial to me who your mom was.”

“Just promise me this,” Stem said. “Promise you won’t tell the others.”

“Why would I tell the others?”

“I’ll kill you if you tell.”

“Ooh, scary,” Denny said.

By now the little boys were taking notice. They’d stopped playing, and they were gaping at Stem. Tommy said, “Dad?”

“Go downstairs,” Stem told him. “The three of you.”

“But, Dad—”

“Now!” Stem said.

They stumbled to their feet and left, looking back at him as they went. Sammy was still clutching a plastic tow truck. Denny winked at him when he walked past.

“Swear to it,” Stem told Denny.

“Okay! Okay!” Denny said, holding up both hands. “Uh, Stem, are you aware how fast that glue dries? You might want to fit those pieces together.”

“Swear on your life that you will never let on to a soul.”

“I swear on my life that I will never let on to a soul,” Denny repeated solemnly. “I don’t get it, though. Why do you care?”

“I just do, all right? I don’t have to give you a reason,” Stem said. But then he said, “I read someplace that even brand-new babies recognize their mothers’ voices. Did you know that? They learn them in the womb. From the moment they’re born, it’s their mothers’ voices they prefer. And I thought, ‘Gosh, I wonder what voice I preferred, back then.’ It seemed kind of sad to me that there was some voice I’d been craving all my life but never got to hear, at least not past the first little bit. And now look: it was B. J. Autry’s voice – that gravelly rasp of hers and that trashy way of talking. When you think of how Abby talks, I mean talked! I should have belonged to Abby.”

“So?” Denny said. “And eventually you did. Happy endings all around.”

“But you remember how the family mocked B. J. behind her back. They’d wince when she gave that laugh of hers; they’d make faces at each other when she was holding forth about something. ‘Oh, you know me; I just say it like it is,’ she’d say. ‘I tell it like I see it; I’m not one to mince my words.’ As if that were something to brag about! And then everybody would share these secret glances, all round the table. So now I think, ‘God, I’d die of shame if they found out she was my mother.’ But I’m ashamed of feeling ashamed of her, too. I start thinking that the family had no right to act so snooty about her. I don’t know what to think! Sometimes it’s like I’m mourning what I missed out on: my real mother was sitting right there at our dining-room table and I never had an inkling, and it makes me mad as hell at Abby for not telling me – for that stupid, stupid contract. She wouldn’t allow my own mother to tell me I was her son! And if B. J. had ever wanted me back, oh, Abby was happy to hand me over. ‘Here you are, then’—easy come, easy go. And Dad: can you believe him? He told me he would have handed me over from the outset.”

“You talked to Dad about this?”

“Well, guess what,” Stem said, not appearing to hear him. “B. J. never did want me back, as it turned out. She looked straight across the table at me and she didn’t want me. She hardly ever saw me. She could have seen me any time, as often as she cared to, but she only came around now and then, two or three times a year.”

“So what? You didn’t even like her. You just said you hated her voice.”

“Still, she was my mother. One woman in the world who thinks you’re special – doesn’t every kid deserve that?”

“You had that. You had Abby.”

“Well, sorry, but that wasn’t enough. Abby was your mom. I needed my own.”

“You don’t think Abby thought you were special?” Denny asked.

Stem was silent. He stared down at the drawer in his hands.

“Come on,” Denny said. “She thought even the back of your neck was special. If she hadn’t, you’d have led a very different life, believe me. You’d have been shunted around who knows where, rootless, homeless, stuck in foster care someplace, and you’d probably have turned into one of those misfit guys who have trouble keeping a job, or staying married, or hanging on to their friends. You’d have felt out of place wherever you went; there’d be nowhere you belonged.”

He stopped. Something in his voice made Stem look up at him, but then Denny said, “Ha! You know what this proves.”

“What.”

“You’re just following the family tradition, is all, the wish-I-had-what-somebody-else-has tradition – till they do have it. Like old Junior with his dream house, or Merrick with her dream husband. Sure! This could be the family’s third story. ‘Once upon a time,’ ” Denny intoned theatrically, “ ‘one of us spent thirty years craving his real mother’s voice, but after he found it, he realized he didn’t like it half as much as his fake mother’s voice.’ ”

Stem gave a thin, unhappy smile.

“Damn. You’re more of a Whitshank than I am,” Denny said.

Then he said, “That glue’s bone-dry by now; didn’t I warn you? You’ll have to scrape it off and start over.”

And he straightened up from the door frame and went back downstairs.

The family’s real-estate friend dated from the days when Brenda had still been spry enough to be taken for a run now and then in Robert E. Lee Park. Helen Wylie used to walk her Irish setter there, and she and Abby had struck up a conversation. So when she arrived on Saturday morning – a breezy, sensible woman in corduroys and a barn jacket – no extensive instructions were needed. “I already know,” she told Red straight off. “What you want is something solidly built. Prewar, I’m thinking. You were crazy to even consider something in that new building! You want a place that you won’t be ashamed to show to your contractor buddies.”

“Well, you’re right,” Red said. Although he didn’t have any contractor buddies, at least none that would be paying social calls.

“Let’s go, then,” Helen told Amanda. Amanda was the one who had gotten in touch with her, and she would be coming along. Even Red had admitted that he could use some help on this.

The first apartment was near University Parkway – old but well kept, with gleaming hardwood floors. The landlord said the kitchen had been remodeled in 2010. “Who did your work?” Red asked. He screwed up his face when he heard the name.

The second place was a third-floor walk-up. Red was only slightly winded by the time he reached the top of the stairs, but he didn’t argue when Amanda pointed out that this wouldn’t be a good long-term proposition.

The third place did have an elevator, and it was of an acceptable age, but so many dribs and drabs of belongings were crammed inside that it was hard to get any real sense of it. “I’ll be honest,” the super said. “The previous tenant died. His kids will have his stuff moved out within the next two weeks, though, and I’m going to get it cleaned then and give it a fresh coat of paint.”

Amanda sent Helen a dispirited glance, and Helen turned the corners of her mouth down. A mole-colored cardigan sagged on the back of a rocker. A mug sat on the cluttered coffee table with a teabag tag trailing out of it. But Red seemed unfazed. He walked through the living room to the kitchen and said, “Look at this: he had everything arranged so he didn’t have to get up from the table once he’d sat down to breakfast.”

Sure enough, the rickety-looking card table held a toaster, an electric kettle, and a clock radio, all aligned against the wall, with a day-by-day pill organizer in the center where most people would have placed a vase of flowers. In the bedroom, Red said, “There’s a TV you can watch from the bed.” The TV was the heavy, old-fashioned kind, deeper than it was wide, and it stood on the low bureau across from the foot of the bed. “Watch the late news and then go straight to sleep,” Red noted approvingly, although no TV had ever been seen in his bedroom on Bouton Road. But maybe that had been Abby’s choosing. “This seems like a real convenient place for a guy making do on his own,” Red said.

Amanda said, “Yes, but …” and she and Helen exchanged another glance.

“But picture it minus the furnishings,” Helen suggested. “The TV and such will be gone, remember.”

“I could put my set there, though,” Red said.

“Of course you could. But let’s focus on the apartment itself. Do you like the layout? Is it spacious enough? The rooms seem a little small to me. And what about the kitchen?”

“Kitchen is good. Reach across the table, grab your toast straight out of the toaster. Take your heart pills. Turn on the weather report.”

“Yes … The floor is linoleum, did you notice?”

“Hmm? Floor looks fine. I think my folks had a kitchen floor like that in our first house.”

And that settled it. As Amanda told the others later, it appeared to be a question of imagination. Red’s imagination: he had none. He just seemed glad that someone else had arranged things so he wouldn’t need to.

Well, it did make things easier for his children. And they could always do some refurbishing after he’d moved in.

Helen was going to handle the house sale as well. She came in with them after the apartment tour to discuss the arrangements for that, with Stem and Denny joining in. “Such a comfortable old place this is,” she said, looking around the living room. “And of course the porch is a huge draw. It’s going to be a pleasure to show.”

Everyone except Red looked encouraged. Red was gazing toward a nearby newspaper as if he wished he could be reading it.

“But it is still a sluggish market,” Helen said. “And what I’ve learned is, buyers in these times expect perfection. We’ll want to spruce the place up some.”

“Spruce it up?” Red said. “What more could they possibly ask for? Every downstairs room but the kitchen’s got double pocket doors.”

“Oh, yes, I love the—”

“And it’s not often you see an entrance hall like ours, two-story. Or these open transoms with the handsawed fretwork.”

“But it isn’t air-conditioned,” Helen said.

Red said, “Oh, God,” and he slumped in his seat.

“These days—” Helen said.

“Yeah, yeah.”

“It won’t be so hard,” Denny told him. “They’ve got these mini-duct systems now where you won’t need to tear up the walls.”

Red said, “Who do you think you’re talking to? I know all about those systems.”

Denny shrugged.

“Also,” Helen said. She cleared her throat. She said, “This would be your choice entirely, but you might want to consider his-and-her master bathrooms.”

Red raised his head. He said, “Consider what?”

“I wouldn’t bring it up except you do own a contracting firm, so it wouldn’t be such an expense. That master bathroom you have now is gigantic. You could easily divide it in two, with a shower stall in between that’s accessible from both sides. I just saw the most dazzling shower stall, with river-pebble flooring and multiple rainmaker nozzles.”

Red said, “When my father built this house, it had only the one bathroom off the upstairs hall.”

“Well, that was back in the—”

“Then he added the downstairs powder room after we moved in, and we thought we were something special.”

“Yes, you certainly need a—”

“The master bathroom itself he didn’t put in till my sister and I were in high school. What he’d say if he heard about his-and-hers, I can’t even begin to imagine.”

“It’s customary, though, in the finer homes these days. As I’m sure you must have learned in your business.”

“He himself grew up with just a privy,” Red said. He turned to the others. “I bet you didn’t know that about your grandfather, did you?”

They did not. They knew next to nothing about their grandfather, in fact.

“Well, a privy,” Helen said with a laugh. “That would be a hard sell!”

“So we’ll forget about the his-and-hers,” Red told her. “Now, how long do you expect it will take to find a buyer?”

“Oh, once you’ve installed the air conditioning, and maybe upgraded your kitchen counters—”

“Kitchen counters!”

But then he clamped his lips tightly, as if reminding himself not to be difficult.

“It does seem the market’s started looking up,” Helen said. “There was a time there when places were languishing for a year or more, but lately I’ve been averaging, oh, just four to six months, with our more desirable properties.”

“In four to six months it will go to seed,” Red told her. “You know it’s not good for a house to sit empty. It will molder; it will get all forlorn; it will break my heart.”

Amanda said, “Oh, Dad, we would never let that happen. We’ll come and, I don’t know, throw family picnics here or something.”

Red just gazed at her miserably, his eyes so empty of light that he seemed almost sightless.

“Be honest,” Jeannie said to Amanda. “Does any little part of you feel relieved that Mom died so suddenly?”

“You mean on account of her lapses,” Amanda said.

“They would only have gotten worse; we can be pretty sure of that. Whatever they were. And Dad would be trying to look after her, and so would Nora; and Denny would have thought of some excuse to leave by then.”

“But maybe it was just, oh, a circulation problem or something, and the doctors could have fixed it.”

“That’s not very likely,” Jeannie said.

They were up in Red’s bedroom on a rainy Sunday afternoon, packing cartons while the others watched a baseball game downstairs. Both of them wore scruffy clothes, and Amanda’s chin was smudged with newspaper ink.

All week they had been packing, any free moment they could find. Separate islands of belongings had begun rising here and there in the house as people put in their requests: Abby’s crafts supplies and her sewing machine in the upstairs hall for Nora, the good china packed in a barrel in the dining room for Amanda. (Red would keep the everyday china, which they were leaving in the cupboard until just before moving day.) Color-coded stickers dotted the furniture – a few pieces for Red’s apartment, a few more for Stem and Jeannie and Amanda, and the vast majority for the Salvation Army.

Jeannie and Amanda dragged a filled carton between them out to the hall, where one of the boys could come get it later. Then Jeannie unfolded another carton and ran tape across the bottom flaps. “If I know Mom,” she said, “she’d have refused any surgery anyhow.”

“It’s true,” Amanda said. “Her advance directive basically asked us to put her out on an ice floe if she developed so much as a hangnail.” She was collecting framed photos from the top of Abby’s bureau. “I’m going to pack these up for Dad,” she told Jeannie.

“Will he have space for them?”

“Oh, maybe not.”

She studied the oldest photo – a snapshot of the four of them laughing on the beach, Amanda barely a teenager and the rest of them still children. “We look like we were having such a good time,” she said.

“We were having a good time.”

“Well, yes. But things could get awfully fraught, now and then.”

“At the funeral,” Jeannie said, “Marilee Hodges told me, ‘I always used to envy you and that family of yours. The bunch of you out on your porch playing Michigan poker for toothpicks, and your two brothers so tall and good-looking, and that macho red pickup your dad used to drive with the four of you kids rattling around in the rear.’ ”

“Marilee Hodges was a ninny,” Amanda said.

“Goodness, what brought that on?”

“It was hell riding in that truck bed. I doubt it was even legal. And I believe children should have their own rooms. And Mom could be so insensitive, so clueless and obtuse. Like that time she sent Denny for psychological testing and then told all of us his results.”

“I don’t remember that.”

“Supposedly one of those inkblot thingies showed he’d been disappointed in his early childhood by a woman. ‘What woman could that have been?’ Mom kept asking us. ‘He didn’t know any women!’ ”

“I don’t remember a thing about it.”

“It was pretty clear she loved him best,” Amanda said, “even though he drove her crazy.”

“You’re just saying that because you’ve got only one child,” Jeannie told her. “Mothers don’t love children best; they love them—”

“—differently, is all,” Amanda finished for her. “Yes, yes, I know.” Then she held up a photo of Stem at age four or five. “Would Nora like this, do you think?”

Jeannie squinted at it. “Put it in her box,” she suggested.

“And what do I do with this one of Denny?”

“Does he have a box?”

“He says he doesn’t want anything.”

“Start a box for him anyhow. I bet wherever he lives is nothing but bare walls.”

“I asked him yesterday,” Amanda said, “whether he had let his landlady know that he was coming back, and all he said was, ‘We’re working on that.’ ”

“ ‘Working on that’! What is that supposed to mean?”

“He’s so darn secretive,” Amanda said. “He pokes and pries into our lives, but then he gets all paranoid when we ask about his.”

“I think he’s mellowing, though,” Jeannie told her. “Maybe losing Mom has done that. When I was taking down the wall of photos in his room, I asked him, ‘Should I just chuck these?’ All those photos of the Daltons, those chunky aunts from the forties with their shoulder pads and thick stockings. But Denny said, ‘Oh, I don’t know; that seems kind of harsh, don’t you think?’ I said, ‘Denny?’ I actually knocked on the side of his head with my knuckles. ‘Knock knock,’ I said. ‘Is that you in there?’ ”

“Good,” Amanda said promptly. “Let’s give him these.” And she reached for a sheet of newspaper and started wrapping a photo.

“Denny’s getting nicer and Stem is getting crankier,” Jeannie said. “And Dad! He’s being impossible.”

“Oh, well, Dad,” Amanda said. “It’s like you can’t say anything right to him.” She placed the wrapped photo in the carton Jeannie had just set up. “He’s been fretting about the house so,” she said. “How long it will take to sell it, how people might not appreciate it … So I asked him, I said, ‘Should we try and get in touch with the Brills?’ ”

“The Brills,” Jeannie repeated.

“The original-owner Brills. The ones who had the house built in the first place.”

“Yes, I know who they are, Amanda, but wouldn’t they be dead by now?”

“Not the sons, I don’t imagine. The sons were only in their teens when Dad was a little boy. So I said, ‘What if all these years the sons have been pining over this house and wishing they still lived here?’ You remember what one of them said when their mother said they were moving. ‘Aw, Ma?’ he said. Well, you would think I’d suggested lighting a match to the place. ‘What are you thinking?’ Dad asked me. ‘Where did you get such a damn-fool notion as that? Those two spoiled Brill boys are not ever getting their hands on this house. Put it right out of your mind,’ he said. I said, ‘Well, sorry. Gee. My mistake entirely.’ ”

“It’s grief,” Jeannie told her. “He’s just lost the love of his life, bear in mind.”

“Which loss are you talking about – Mom or the house?”

“Well, both, I guess.”

“Huh,” Amanda said. “I never heard before that grief makes people bad-tempered.”

“Some it does and some it doesn’t,” Jeannie said.

They had reached that stage of packing where it seemed they’d created more mess than they had cleared out. Several half-filled cartons sat open around the room – the photos in a carton for Denny, blankets in a carton for Red, a mass of Abby’s sweaters in a carton for Goodwill. With each sweater there had been a debate—“Don’t you want to take this? You would look good in this!”—but after holding it up for a moment, one or the other of them would sigh and let it fall into the carton with the rest. The rug was linty, the floor was strewn with cast-off hangers and dry-cleaner’s bags, and a hard gray light from the stripped windows gave the room a bleak and uncared-for look.

“You should have heard Dad’s reaction when I told him he should maybe leave this bed behind and take a single,” Amanda said.

“Well, I can understand: he wants the bed that he’s used to.”

“You haven’t seen his apartment, though. It’s dinky.”

“It’s going to feel weird to visit him there,” Jeannie said.

“Yes, last night I had this peculiar moment when I was saying goodbye to him. He asked, ‘Don’t you want to take some leftovers with you?’ Mom’s thing to ask! ‘It’ll save you from cooking supper,’ he said, ‘one of the nights this week.’ Oh, Lord, isn’t it strange how life sort of … closes up again over a death.”

“Even the little boys have adjusted,” Jeannie said. “That’s kind of surprising, when you think about it – that children figure out so young that people die.”

“It makes you wonder why we bother accumulating, accumulating, when we know from earliest childhood how it’s all going to end.”

Amanda was looking around at the accumulation as she spoke – at the cartons and the stacked pillows and the tied-up bales of old magazines and the lamps with their shades removed. And that was nothing compared with the clutter elsewhere in the house – the towers of faded books teetering on the desk in the sunroom, the rolled carpets in the dining room, the stemware tinkling on the buffet each time the little boys stampeded past. And out on the front porch, waiting to go to the dump, the miscellaneous items that no one on earth wanted: a three-legged Portacrib, a broken stroller, a high chair missing its tray, and a string-handled shopping bag full of cracked plastic toys with somebody’s small, clumsy pottery house perched on top, painted in kindergarten shades of red and green and yellow.