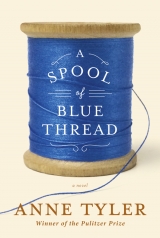

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“This was at a savings and loan,” Dane said. “I have no plans to make my career in savings and loans, believe me.”

“The point is, what reputation you get. What opinion your community has of you. Now, you may not feel that a savings and loan is your be-all and your end-all …”

How could this man have been the hero of Mrs. Whitshank’s romance? Whether you found it dashing or tawdry, at least it had been a romance, complete with intrigue and scandal and a wrenching separation. But Junior Whitshank was dry as a bone, droning on relentlessly while the other diners ate their food in dogged silence. Only his wife was looking at him, her face alight with interest as he discussed the value of hard labor, then the deplorable lack of initiative in the younger generation, then the benefits conferred by having lived through the Great Depression. If young folks today had lived through a depression the way he had lived through a depression – but then he broke off to call, “Ah! Going out with your buddies?”

It was Merrick he was addressing. She was crossing the hall, heading toward the front door, but she stopped and turned to face him. “Yup,” she said. “Don’t wait supper.” Her hair had become a mass of bubbly black curls that bounced all over her head.

“Merrick’s fiancé, now; he’s gone into his family’s business,” Mr. Whitshank told the others. “Doing a fine job too, I gather. Course we couldn’t call him a practical fellow – doesn’t know how to change his own oil, even; can you believe it?”

“Well, toodle-oo,” Merrick said, and she trilled her fingers at the table and left. Her father blinked but then picked up his thread – the “spoiledness” of the rich and their complete inability to do for themselves – but Abby had stopped listening. She felt suddenly hopeless, defeated by his complacent, self-relishing drawl, his not-quite-right “I and your dad” and his trying-too-hard Northern i’s, his greedy attention to the details of class and privilege. But Mrs. Whitshank went on smiling at him, while Red just helped himself to another slice of tomato. Earl was stacking biscuits three high on the rim of his plate, as if he planned to take them home. Ward had a shred of chicken stuck to his lower lip.

“All of which,” Mr. Whitshank was saying, “shows why you would never. Ever. Under any circumstances. Knuckle under to these people. I’m talking to you, Redcliffe.”

Red stopped salting his tomato slice and looked up. He said, “Me?”

“Why you would not kowtow to them. Butter them up. Soft-soap them. Tell them, ‘Yes, Mr. Barkalow,’ and, ‘No, Mr. Barkalow,’ and, ‘Whatever you say, Mr. Barkalow. Oh, we wouldn’t want to discommode you, Mr. Barkalow.’ ”

Red was cutting into his tomato slice now, not meeting his father’s eyes or even appearing to hear him, but his cheekbones had a raw, scratched look as if they’d been raked by someone’s fingernails.

“ ‘Oh, Mr. Barkalow,’ ” Mr. Whitshank said in a simpering voice. “ ‘Is this mutually agreeable to you?’ ”

“We got that trunk down, boss,” Landis said. “Got her just about flat to the ground.”

Abby wanted to hug him.

Mr. Whitshank was preparing to say more, but he paused and looked over at Landis. “Oh,” he said. “Well, good. Now all’s we have to do is wait for Mitch to finish lunch at his durn mother-in-law’s.”

“I wouldn’t hold my breath, boss. You ever met his mother-in-law? Woman is a cooking fiend. Seven children, all of them married, all with children of their own, and every Sunday after church they all get together at her house and she serves three kinds of meat, two kinds of potato, salad, pickles, vegetables …”

Abby sat back in her chair. She hadn’t realized how tightly she had been clenching her muscles. She wasn’t hungry anymore, and when Mrs. Whitshank urged another piece of chicken on her she mutely shook her head.

“Another thing,” Red said.

He had paused next to Abby as the men were leaving the dining room. Abby, collecting a fistful of dirty silverware, turned to look at him.

“If you’re thinking you shouldn’t come to the wedding because it’s too short of a notice,” he said, “that wouldn’t be a problem, I promise. A lot of people Merrick invited are staying away. All those friends of Pookie Vanderlin’s, and their moms and dads too – they’ve mostly said no. We’re going to end up with way too much food at the reception, I bet.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” Abby told him, and she gave him a quick pat on the arm as if to thank him, but what she really meant to convey was that she had already put his father’s tirade out of her mind and she hoped that he would do the same.

Dane, waiting for Red in the doorway, sent her a wink. He liked to poke fun at Red’s devotion sometimes, referring to him as “your feller.” Usually this made her smile, but today she just went back to her table clearing, and after a moment he and Red walked on out to join the others.

She set the silverware next to the kitchen sink where Mrs. Whitshank was washing glasses, and then she returned to the dining room. There stood Mr. Whitshank, scooping a gooey chunk of peach cobbler from the baking dish with his fingers. He froze when he saw Abby, but then he lifted his chin defiantly and popped the chunk into his mouth. With showy deliberation, he wiped his fingers on a napkin.

Abby said, “It must be hard to be you, Mr. Whitshank.”

His fingers stilled on the napkin. He said, “What’s that you say?”

“You’re glad your daughter’s marrying a rich boy but it irks you rich boys are so spoiled. You want your son to join the gentry but you’re mad when he’s polite to them. I guess you just can’t be satisfied, can you?”

“Missy, you’ve got no business taking that tone with me,” he said.

Abby felt as if she were about to run out of breath, but she stood her ground. “Well?” she asked. “Can you?”

“I’m proud of both my children,” Mr. Whitshank said in a steely voice. “Which is more than your daddy can say for you, I reckon, with that disrespectful tongue of yours.”

“My father is very proud of me,” she told him.

“Well, maybe I shouldn’t be surprised, considering where you come from.”

Abby opened her mouth but then closed it. She snatched up the cobbler dish and marched out to the kitchen with it, her back very straight and her head high.

Mrs. Whitshank had left off washing dishes to start drying some of those that were sitting on the drain board. Abby took the towel from her, and Mrs. Whitshank said, “Why, thank you, honey,” and returned to the sink. She didn’t seem to notice how Abby’s hands were shaking. Abby felt bitterly triumphant but also wounded in some way – cut to the quick.

How dare he say a word about where she came from? He of all people, with his shady, shameful past! Her family was very respectable. They had ancestors they could brag about: a great-great-grandfather, for instance, who had once rescued a king. (Granted, the rescue was merely a matter of helping to lift a carriage wheel out of a rut in the road, but the king had nodded to him personally, it was believed.) And a great-aunt out west who’d gone to college with Willa Cather, although it was true that the great-aunt hadn’t known at the time that Willa Cather existed. Oh, there was nothing lower-class about the Daltons, nothing second-rate, and their house might be on the smallish side but at least they got along with their neighbors.

Mrs. Whitshank was talking about dishwashing machines. She just didn’t see the need, she was saying. She said, “Why, some of my nicest conversations have been over a sinkful of dishes! But Junior thinks we ought to get a machine. He’s all for going out and buying one.”

“What does he know about it?” Abby demanded.

Mrs. Whitshank was quiet a moment. Then, “Oh,” she said, “he just wants to make my life easier, I guess.”

Abby fiercely dried a platter.

“People don’t always understand Junior,” Mrs. Whitshank said. “But he’s a better man than you know, Abby, honey.”

“Huh,” Abby said.

Mrs. Whitshank smiled at her. “Could you check out on the porch, please,” she asked, “and see if there’s any dishes?”

Abby was glad to leave. She might have said something she’d be sorry for.

No one was sitting on the porch. She picked up Merrick’s cereal bowl and her spoon, and then she straightened and surveyed the lawn. At the moment, both chainsaws were silent. The air seemed oddly bright; evidently that naked trunk had made more difference than she had suspected. It was lying flat now, pointing toward the street, and Landis was untying a length of rope that had been looped around its circumference. Dane had paused for a cigarette, Earl and Ward were loading the wheelbarrow, and Red was standing next to the sheared-off stump with his head bowed.

From his posture, Abby thought at first that he was brooding about what had happened at lunch, and she turned away quickly so he wouldn’t know she had seen. But in the act of turning, she realized that what he was doing was counting tree rings.

After all Red had been through today – the grueling physical effort and the din and the punishing heat, the altercation with the neighbor and the painful scene with his father – Red was calmly studying that stump to find out how old it was.

Why did this hearten her so? Maybe it was the steadiness of his focus. Maybe it was his immunity to insult, or his lack of resentment. “Oh, that,” he seemed to be saying. “Never mind that. All families have their ups and downs; let’s just figure the age of this poplar.”

Abby felt buoyed by a kind of airiness at her center, like the airiness of the lawn once that trunk had been felled. She stepped back into the house so lightly that she made almost no sound at all.

“What’s going on out there?” Mrs. Whitshank asked. She was wiping a counter; the last of the pots and pans had been dried and put away.

Abby said, “Well, they got the trunk down, but Mitch hasn’t shown up yet. Dane is taking a cigarette break, and Ward and Earl and Landis are clearing the yard, and Red is counting tree rings.”

“Tree rings?” Mrs. Whitshank asked. Then, perhaps imagining that Abby had no knowledge whatsoever of the natural world, she said, “Oh! He must be guessing its age.”

“He was just standing there, after all that fuss, wondering how old a poplar was,” Abby said, and all at once she felt on the verge of tears; she had no idea why. “He’s a good man, Mrs. Whitshank,” she said.

Mrs. Whitshank glanced up in surprise, and then she smiled – a serene, contented, radiant smile that turned her eyes into curls. “Why, yes, honey, he is,” she said.

Then Abby went out to the porch again and settled in the swing. It was the prettiest afternoon, all breezy and yellow-green with a sky the unreal blue of a Noxzema jar, and in a minute she was going to tell Red she’d like to ride with him to the wedding. For now, though, she was saving that up – hugging it close to her heart.

She nudged a porch floorboard with her foot to set the swing in motion, and she swung slowly back and forth, absently tracing the familiar, sandy-feeling undersides of the armrests with her fingertips. Her eyes were on Dane now; she watched him with a distant feeling of sorrow. She saw how he dropped his cigarette, how he ground it beneath his heel, how he picked up his axe and sauntered over to a branch. What a world, what a world. And then the line that came after that one: “Who would have thought,” the witch had asked, “that a good little girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness?”

But Abby stood up from the swing, even so, and started walking toward Red, and with every step she felt herself growing happier and more certain.

PART THREE. Bucket of Blue Paint

10

EVERY GROUND-FLOOR ROOM but the kitchen had double pocket doors, and above each door was a fretwork transom for the air to circulate in the summer. The windows were fitted so tightly that not even the fiercest winter storm could cause them to rattle. The second-floor hall had a chamfered railing that pivoted neatly at the stairs before descending to the entrance hall. All the floors were aged chestnut. All the hardware was solid brass – doorknobs, cabinet knobs, even the two-pronged hooks meant to anchor the cords of the navy-blue linen window shades that were brought down from the attic every spring. A ceiling fan with wooden blades hung in each room upstairs and down, and out on the porch there were three. The fan above the entrance hall had a six-and-a-half-foot wingspan.

Mrs. Brill had wanted a chandelier in the entrance hall – a glittery one, all crystal, shaped like an upside-down wedding cake. Silly woman. Junior had dissuaded her by pointing out the impracticality: any time the tiniest cobweb was spotted trailing from a prism, he would need to send a workman over with a sixteen-foot stepladder. (He failed to disclose that for another client, he had once designed an ingenious cable-and-winch lift system to raise and lower a chandelier at will.) His main objection, of course, was that a chandelier would not have been in keeping with the house. This was a plain house, in the way that a handcrafted blanket chest is plain – simple, but impeccably built, as Junior, who had built it, should know. He had overseen every detail, setting his hand to every part of it except those parts that somebody else could do better, like the honeycombing of tiny black-and-white ceramic tiles in the bathroom, laid by two brothers from Little Italy who didn’t speak any English. The stairway, though, with the newel posts running clean through the hand-cut openings in the treads, and those pocket doors that glided almost silently into their respective walls: those were Junior’s. He was a brash and hasty man in all other areas of life, a man who coasted through stop signs without so much as a toe on the brake, a man who bolted his food and guzzled his drinks and ordered a stammering child to “come on, spit it out,” but when it came to constructing a house he had all the patience in the world.

Mrs. Brill had also wanted velvet-flocked wallpaper in the living room, fitted carpets in the bedrooms, and red-and-blue stained glass in the fanlight above the front door. None of which she got. Ha! Junior won just about every argument. Mostly, as with the chandelier, he cited impracticalities, but when he needed to he was not averse to bringing up the issue of taste. “Now, I don’t know why, Mrs. Brill,” he would say, “but that is just not done. The Remingtons didn’t do that, nor the Warings, either”—naming two families in Guilford whom Mrs. Brill especially admired. Then Mrs. Brill would retreat—“Well, you know best, I suppose”—and Junior would proceed as he had originally intended. This was the house of his life, after all (the way a different type of man would have a love of his life), and against any sort of logic he clung to the conviction that he would someday be living here. Even after the Brills moved in and their cluttery decorations choked the airy rooms, he remained serenely optimistic. And when Mrs. Brill started talking about how isolated she felt, how far from downtown, when she went to pieces after she found those burglar tools in the sunroom, he heard the click of his world settling into its rightful place. At last, the house would be his.

As it had been all along, really.

Sometimes, in the weeks when he was sprucing the place up before he installed his family, he drove over in the early morning just to take a walk-through, to relish the thrillingly empty rooms and the non-squeaking floorboards and the sturdy faucet handles above the bathroom sink. (Mrs. Brill had wanted handles she’d seen in a Paris hotel, faceted crystal knobs the size of Ping-Pong balls. In Junior’s opinion, though, the only sensible design was a chubby white porcelain cross – easiest to turn with soapy fingers – and for once Mr. Brill had spoken up and agreed with him.)

He liked to gaze up the stairs and imagine his daughter sweeping down them, an elegant young woman in a white satin wedding gown. He envisioned the dining-room table lined with a double row of grandchildren, mostly boys, his son’s boys to carry on the Whitshank name. They would all have their faces turned in Junior’s direction, like sunflowers turned to the sun, listening to him hold forth on some educational topic. Maybe he could assign a topic each night at the start of the meal – music, or art, or current events. A ham or perhaps a roast goose would sit in front of him waiting to be carved, and the water would be served in stemmed goblets, and the salad forks would have been refrigerated ahead of time as he had observed the maid doing in the Remingtons’ house in Guilford.

Everything till now had been makeshift – his ragtag upbringing, his hidey-hole courtship, his limping-along marriage, and his shabby little rented house in a rundown neighborhood. But now that was about to change. His real life could begin.

Then Linnie Mae had to go and interfere with the porch swing.

In the Brills’ time, the porch swing had been an ugly white wrought-iron affair featuring sharp-edged curlicues that gouged a person’s spine. Its rust-pocked figure-eight hooks made a screechy, complaining sound, and the heavy chains could seriously pinch your fingers if you gripped them wrong. But Mrs. Brill had swung in that swing as a little girl, she’d told Junior, and it was clear from the lingering way she spoke how fondly she looked back on that little girl, how she cherished the notion of her cute little childhood self. So Junior had had to allow it.

When the Brills moved out, they left behind all their porch furniture because they were going to an apartment. Mrs. Brill told Junior, in a sad little voice, to be sure and look after her swing, and Junior said, “Yes, ma’am, I’ll certainly do that.” The moment they were gone, though, he climbed up on a ladder and unhooked the swing himself. He knew what he wanted in its stead: a plain wooden bench swing varnished in a honey tone, with a row of lathed spindles forming the back and supporting each armrest. It should hang by special ropes that were whiter and softer than ordinary ropes, easier on the hands, and when it moved there should be no sound at all, or at most just a genteel creak such as he imagined you would hear from the sails on a sailboat. He had seen such a swing back home, at Mr. Muldoon’s. Mr. Muldoon managed the mica mines, and his house had a long front porch with varnished floorboards, and the steps were varnished as well, and so was the swing.

Junior couldn’t find this swing ready-made and he had to commission one. It cost a fortune. He didn’t tell Linnie how much. She asked, because money was an issue; the down payment on the house had just about ruined them. But he said, “What difference does it make? There’s not a chance on this earth I would live in a place with a white lace swing out front.”

It arrived raw, as he’d specified, so that it could be finished to the shade he envisioned. He had Eugene, his best painter, see to that. Another of his men spliced the ropes to the heavy brass hardware, a fellow from the Eastern Shore who knew how such things were done. (And who whistled when he saw the brass, but Junior had his own private hoard and it was not his fault there was a war on.) When the swing was hung, finally – the grain of the wood shining through the varnish, the white ropes silky and silent – he felt supremely satisfied. For once, something he’d dreamed of had turned out exactly as he had planned.

Up to this point, Linnie Mae had barely visited the house. She just didn’t seem as excited about it as Junior was. He couldn’t understand that. Most women would be jumping up and down! But she had all these quibbles: too expensive, too hoity-toity, too far from her girlfriends. Well, she would come around. He wasn’t going to waste his breath. But once the swing was hung he was eager for her to see it, and the next Sunday morning he suggested taking her and the kids to the house in the truck after they got back from church. He didn’t mention the swing because he wanted it to kind of dawn on her. He just pointed out that since it was only a couple of weeks till moving day, maybe she’d like to carry over a few of those boxes she’d been packing. Linnie said, “Oh, all right.” But after church she started dragging her heels. She said why didn’t they eat dinner first, and when he told her they could eat after they got back she said, “Well, I’ll need to change out of my good clothes, at least.”

“What do you want to do that for?” he asked. “Go like you are.” He hadn’t brought it up yet, but he was thinking that after they’d moved in, Linnie should give more thought to how she dressed. She dressed like the women back home dressed. And she sewed most of her clothes herself, as well as the children’s. There was something thick-waisted and bunchy, he had noticed, about everything that his children wore.

But Linnie said, “I am not lugging dusty old boxes in my best outfit.” So he had to wait for her to change and to put the kids in their play clothes. He himself kept his Sunday suit on, though. Until now their future neighbors, if they ever peeked out their windows (and he would bet they did), would have seen him only in overalls, and he wanted to show his better side to them.

In the truck, Merrick sat between Junior and Linnie while Redcliffe perched on Linnie’s lap. Junior chose the prettiest streets to drive down, so as to show them off to Linnie. It was April and everything was in bloom, the azaleas and the redbud and the rhododendron, and when they reached the Brills’ house – the Whitshanks’ house! – he pointed out the white dogwood. “Maybe when we’re moved in you could plant yourself some roses,” he told Linnie, but she said, “I can’t grow roses in that yard! It’s nothing but shade.” He held his tongue. He parked down front, although with all they had to unload it would have made more sense to park in back, and he got out of the truck and waited for her to lift the children out, meanwhile staring up at the house and trying to see it through her eyes. She had to love it. It was a house that said “Welcome,” that said “Family,” that said “Solid people live here.” But Linnie was heading toward the rear of the truck where the boxes were. “Forget about those,” Junior told her. “We’ll see to them in a minute. I want you to come on up and get to know your new house.”

He set a hand on the small of her back to guide her. Merrick took his other hand and walked next to him, and Redcliffe toddled behind with his homemade wooden tractor rattling after him on a string. Linnie said, “Oh, look, they left behind their porch furniture.”

“I told you they were doing that,” he said.

“Did they charge you for it?”

“Nope. Said I could have it for free.”

“Well, that was nice.”

He wasn’t going to point out the swing. He was going to wait for her to notice it.

There was a moment when he wondered if she would notice – she could be very heedless, sometimes – but then she came to a stop, and he stopped too and watched her taking it in. “Oh,” she said, “that swing’s real pretty, Junior.”

“You like it?”

“I can see why you would favor it over wrought iron.”

He slid his hand from the small of her back to cup her waist, and he pulled her closer. “It’s a sight more comfortable, I’ll tell you that,” he said.

“What color you going to paint it?”

“What?”

“Could we paint it blue?”

“Blue!” he said.

“I’m thinking a kind of medium blue, like a … well, I don’t know what shade exactly you would call it, but it’s darker than baby blue, and lighter than navy. Just a middling blue, you know? Like a … maybe they call it Swedish blue. Or … is there such a thing as Dutch blue? No, maybe not. My aunt Louise had a porch swing the kind of blue I’m thinking of; my uncle Guy’s wife. They lived over in Spruce Pine in this cute little tiny house. They were the sweetest couple. I used to wish my folks were like them. My folks were more, well, you know; but Aunt Louise and Uncle Guy were so friendly and outgoing and fun-loving and they didn’t have any children and I always thought, ‘I wish they’d ask if I could be their child.’ And they sat out in their porch swing together every nice summer evening, and it was a real pretty blue. Maybe Mediterranean blue. Do they have such a color as Mediterranean blue?”

“Linnie Mae,” Junior said. “The swing is already painted.”

“It is?”

“Or varnished, at least. It’s finished. This is how it’s going to be.”

“Oh, Junie, can’t we paint it blue? Please? I think how best to describe that blue is ‘sky blue,’ but by that I mean a real sky, a deep-blue summer sky. Not powder blue or aqua blue or pale blue, but more of a, how do you say—”

“Swedish,” Junior said through set teeth.

“What?”

“It was Swedish blue; you had it right the first time. I know because every goddamn house in Spruce Pine had Swedish-blue porch furniture. You’d think they’d passed a law or something. It was a common shade. It was common and low-class.”

Linnie was looking at him with her mouth open, and Merrick was tugging his hand to urge him toward the house. He wrung his fingers free and charged on up the walk, leaving the others to follow. If Linnie said one more word, he was going to fling back his head and roar like some kind of caged beast. But she didn’t.

The main thing he needed to do before they moved in was add a back porch. All the house had now was a little concrete stoop – one of the few battles with the Brills that Junior had lost, although he had pointed out to them repeatedly that their architect had provided no space for the jumble of normal life, the snow boots and catchers’ masks and hockey sticks and wet umbrellas.

Junior always made a spitting sound when someone mentioned architects.

He didn’t have men to spare these days because of the war. Two of them had enlisted right after Pearl Harbor, and one had gone to work at the Sparrows Point Shipyard, and a couple more had been drafted. So what he did, he took Dodd and Cary off the Adams job and set them to roughing out the porch, after which he finished the rest on his own. He went over there in the evenings, mostly, using the last of the natural light for the outside work and after that moving inside (the porch was enclosed at one end) to continue under the glare of the ceiling fixture his electrician had installed.

He liked working by himself. Most of his men, he suspected – or the younger ones, at least – found him stern and forbidding. He didn’t set them straight. They’d be talking woman troubles and trading tales of weekend binges, but the instant he showed himself they would shut up, and inwardly he would smile because little did they know. But it was best they never found out. He still did some hands-on work; he wasn’t too proud for that, but generally he did it off in some separate room – cutting dadoes, say, while the rest of them were framing an addition. They’d be gossiping and joking and teasing one another, but Junior (usually so talkative) worked in silence. In his head, a tune often played without his deciding which one—“You Are My Sunshine” for one task, say, and “Blueberry Hill” for another – and his work would fall into the tempo of the song. One long week, installing a complicated staircase, he found himself stuck with “White Cliffs of Dover” and he thought he would never finish, he was moving so slowly and mournfully. Although it did turn out to be a very well made staircase. Oh, there was nothing like the pleasure of a job done right – seeing how tidily a tenon fit into a mortise, or how the proper-size shim, properly shaved, properly tapped into place, could turn a joint nearly seamless.

A couple of days after he took Linnie to visit the house, he drove over there around four p.m. and parked in the rear. As he was stepping out of the truck, though, he saw something that stopped him dead in his tracks.

The porch swing sat next to the driveway, resting on a drop cloth.

And it was blue.

Oh, God, an awful blue, a boring, no-account, neither-here-nor-there Swedish blue. It was such a shock that he had a moment when he wondered if he was hallucinating, experiencing some taunting flash of vision from his youth. He gave a kind of moan. He slammed the truck door shut behind him and walked over to the swing. Blue, all right. He bent to set a finger on one armrest and it came away tacky, which was no surprise because up close, he could smell the fresh paint.

He looked around quickly, half sensing he was being watched. Someone was lurking in the shadows and watching him and laughing. But no, he was alone.

He had the key out of his pocket before he realized the back door was already open. “Linnie?” he called. He stepped inside and found Dodd McDowell at the kitchen sink, blotting a paintbrush on a splotched rag.

“What in the hell do you think you’re doing?” Junior asked him.

Dodd spun around.

“Did you paint that swing?” Junior asked him.

“Why, yes, Junior.”

“What for? Who told you you could do that?”

Dodd was a very pale, bald-headed man with whitish-blond eyebrows and lashes, but now he turned a deep red and his eyelids grew so pink that he looked teary. He said, “Linnie did.”

“Linnie!”

“Did you not know about it?”

“Where did you see Linnie?” Junior demanded.

“She called me on the phone last night. Asked if I would pick up a bucket of Swedish-blue high-gloss and paint the porch swing for her. I thought you knew about it.”

“You thought I’d hunt down solid cherry, and pay an arm and a leg for it, and put Eugene to work varnishing it in a shade to look right with the porch floor, and then have you slop blue paint on it.”

“Well, I didn’t know. I figured: women. You know?” And Dodd spread his hands, still holding the brush and the rag.

Junior forced himself to take a deep breath. “Right,” he said. “Women.” He chuckled and shook his head. “What’re you going to do with them? But listen,” he said, and he sobered. “Dodd. From now on, you take your orders from me. Understand?”

“I hear you, Junior. Sorry about that.”

Dodd still looked as if he were about to cry. Junior said, “Well, never mind. It’s fixable. Women!” he said again, and he gave another laugh and then turned and walked back out and shut the door behind him. He just needed a little time to get ahold of himself.