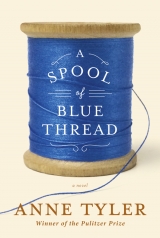

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

PART FOUR. A Spool of Blue Thread

14

YEARS AGO, when the children were small, Abby had started a tradition of hanging a row of ghosts down the length of the front porch every October. There were six of them. Their heads were made of white rubber balls tied up in gauzy white cheesecloth, which trailed nearly to the floor and wafted in the slightest breeze. The whole front of the house took on a misty, floating look. On Halloween the trick-or-treaters would have to bat their way through diaphanous veils, the older ones laughing but the younger ones on the edge of panic, particularly if the night was windy and the cheesecloth was lifting and writhing and wrapping itself around them.

Stem’s three little boys clamored to have the ghosts put up this year the same as always, but Nora said it couldn’t be done. “Halloween isn’t till Wednesday,” she told them. “We’ll be gone by then.” They were vacating the house on Sunday – the earliest date that Red was allowed into his apartment. The plan was for all of them to be resettled by the start of the work week.

But Red overheard, and he said, “Oh, let them have their ghosts, why don’t you? It’ll be their last chance. Then our men can haul them down for us when they come in on Monday morning.”

“Yes!” the little boys shouted, and Nora laughed and flung out her hands in defeat.

So the ghosts were brought forth from their paper-towel carton in the attic, and Stem climbed up on a ladder to hang them from the row of brass hooks screwed into the porch ceiling. Up close, the ghosts looked bedraggled. They were due for one of their periodic costume renewals, but nobody had the time for that with everything else that was going on.

Jeannie and Amanda’s chosen items had already been moved out by the two Hughs in Red’s pickup. Stem’s items were consolidated in a corner of the dining room. Denny’s one box was in his room, but he said he couldn’t take it with him on the train. “We’ll UPS it,” Jeannie decided.

“Or just, maybe, one of you keep it,” he said. And that was how it was left, for the moment.

There were still a few things in the attic, still a few things in the basement – most of them to be discarded. The rest of the house was so empty it echoed. One couch and one armchair stood on the bare floor in the living room, waiting to go to Red’s apartment. The dining-room table had been sent to a consignment shop and the kitchen table stood in its place, ridiculously small and homely, also to go with Red. The larger pieces of furniture had had to be carried out through the front door, because maneuvering them through the kitchen was too difficult; and each time that happened, someone had to scoop up the long trains of the two center ghosts on the porch and anchor them to either side with bungee cords. Even so, Stem and Denny – or whoever was doing the carrying – would be snared from time to time in swags of cheesecloth, and they would duck and curse and struggle to free themselves. “Why on earth these damn things had to be strung up now …” one would say. But nobody went so far as to suggest taking them down.

The whole family had been commenting on how helpful Denny had been lately, but then what did he do? He announced on Saturday evening that he’d be leaving in the morning. “Morning?” Jeannie said. The Bouton Road contingent was eating supper at her house, now that their pots and dishes were packed, and she had just set a pork roast in front of Amanda’s Hugh for carving. She plunked herself down in her chair, still wearing her oven mitts, and said, “But Dad’s moving in the morning!”

“Yeah, I feel bad about that,” Denny said.

“And Stem in the afternoon!”

“What can I do, though?” Denny asked the table in general. “There’s supposed to be a hurricane coming. This changes everything.”

His family looked puzzled. (The hurricane was all over the news, but it was predicted to strike just north of them.) Jeannie’s Hugh said, “Usually people head away from a hurricane, not toward it.”

“Well, but I need to make sure things are battened down at home,” Denny said. There was a pause – a stunned little snag in the atmosphere. “Home” was not a word the family connected with New Jersey. Not even Denny, as far as anyone had known until this moment. Jeannie blinked and opened her mouth to speak. Red looked around the table with a questioning expression; it wasn’t clear that he had heard. Deb was the first to find her voice. She said, “I thought your things were all packed up in a garage, Uncle Denny.”

“They are,” Denny said. “They’re in my landlady’s garage. But my landlady’s on her own; I can’t just tell her to fend for herself, can I?”

Stem asked, “Couldn’t you at least stay till we get Dad moved?”

“The Weather Channel is saying Amtrak might stop the trains by tomorrow afternoon, though. Then I’d be stuck here.”

“Stuck!” Jeannie said, looking offended.

“They’re talking about cutting service to the whole Northeast Corridor.”

“So …” Red said. He drew a deep breath. “So, let’s see if I’ve got this straight. You plan on leaving in the morning.”

“Right.”

“Before I’m in my new place.”

“ ’Fraid so.”

“The thing of it is, though,” Red said, “what about my computer?”

Denny said, “What about it?”

“I was counting on you to set up my Wi-Fi. You know I’m not good at that stuff! What if I can’t connect? What if my laptop goes all temperamental on account of being relocated? What if I try to log on and get nothing, just one of those damn ‘You are not connected to the Internet’ screens? What if I get a whirling beach ball that goes on and on and on, and I can’t get out of it, can’t make contact, can’t hook up anywhere?”

He was asking not only Denny but all of them, sending a wild, scattered gaze around the table. Denny said, “Dad. Amanda’s Hugh knows way more about computers than I do.”

But Amanda’s Hugh said, “Who, me?” And Red just kept staring into one face and then another. Finally Nora, who was seated next to him, set a hand on top of his. “We will take care of all that, I promise, Father Whitshank,” she said.

Red peered at her for a moment, and then he relaxed. No one pointed out that Nora didn’t even have her own e-mail address.

“Well, this is just great,” Jeannie told Denny. She stripped off her oven mitts and slammed them down next to her plate. “You waltz on out whenever you like; everything stops for Lord Denny. Everyone’s just thankful you stayed as long as you did; everyone’s falling all over themselves because it’s such a rare and exalted privilege when you honor us with your presence.”

“The prodigal son,” Nora said contentedly, and she smiled across the table at Petey. “Isn’t it?” she asked him.

But Petey had his mind on the hurricane. He said, “What if you get picked up in the air, Uncle Denny, like the mean neighbor lady in The Wizard of Oz? Do you think that might could happen?”

“You never know,” Denny said, and he chose a roll from the bread basket and gave it a jaunty upward toss before setting it on his plate.

Sunday dawned cloudy and ominous, which was no surprise. Even without a direct hit, the hurricane was bound to spread a swath of wind and rain and electrical glitches throughout the city. Before things could get any worse, therefore, Jeannie and Amanda dropped off their husbands to help with the heavy lifting, and then Amanda collected the three little boys and the dog and took them back to her house so they would be out from underfoot. Jeannie’s assignment was to drive Red to his apartment, along with a small load of kitchen items, and start settling him in. No point making him witness the final dismantling of the house, was everybody’s reasoning. But he kept dragging his heels. Ordinarily a man who hated to impose, he had peevishly refused Nora’s offer of cold cereal for breakfast and requested eggs, although the eggs were packed in a cooler by then and the skillet was in the bottom of a carton. “Dad—” Stem had begun, but Nora had said, “That’s all right. I can fix him eggs in a jiffy.”

Then Red took so long to eat them that he was still at it when Jeannie arrived. She had to wait, barely hiding her impatience, while he slowly and methodically forked up tiny mouthfuls, chewing in a contemplative way as he watched Stem and the two Hughs pass back and forth through the dining room with boxes for Jeannie’s car. “She’s always telling me she should have known what kind of person I was when she found out I didn’t recycle,” Amanda’s Hugh was telling Stem, “but how about what I should have seen, from the note she wrote to complain about it?”

Jeannie jingled her car keys and said, “Dad? Shall we hit the road?”

“Last night I dreamed the house burned down,” he told her.

“What, this house?”

“I could see all the beams and uprights that hadn’t been exposed since when my father built the place.”

“Oh, well …” Jeannie said, and she made a sad little secret face at Nora, who was rewrapping the skillet in newspaper. “That’s understandable, really,” she said. Then she asked, “Did Denny get off okay?”

“No,” Red said, “I think he’s still in bed.”

“In bed!”

Nora said, “I knocked on his door a while ago and he said he was getting up, but maybe he went back to sleep.”

“He was the one who couldn’t wait to leave!”

“Calm yourselves,” Denny said. “I’m up.”

He was standing in the doorway, already wearing his jacket, with a canvas duffel bag hanging from each shoulder and a third, much larger bag at his feet. “Morning, all,” he told them.

Jeannie said, “Well, finally!”

“I see we’ve beaten the rain, so far.”

“Only through pure blind luck,” she said. “I thought you were in such a hurry!”

“I overslept.”

“Have you missed your train?”

“Nah, I’ve still got time.” He looked over at his father, who was single-mindedly pursuing a stray bit of egg white with his fork. “How’re you feeling, Dad?” he asked.

“I’m okay.”

“Excited about your new place?”

“No.”

“There’s coffee,” Nora told Denny.

“That’s all right. I’ll get some at the station.” He waited a beat. “Should I call a cab?” he asked. “Or what?”

He was looking at Jeannie, but Nora was the one who answered. “I can take you,” she told him.

“Seems like you’ve got your hands full.”

He looked again at Jeannie. She flung back her ponytail with an angry snap and said, “Well, I can’t do it. My car’s packed to the gills.”

“It’s no trouble,” Nora said.

“Ready, Dad?” Jeannie asked.

Red set his fork down. He wiped his mouth with a paper towel. He said, “It seems wrong to just walk off and let other folks do the work.”

“But we’re going to work at the new place. You’re the only one who can tell me where you want your spatulas kept.”

“Oh, what do I care where my spatulas are kept?” Red asked too suddenly and too loudly.

But he heaved himself to his feet, and Nora stepped forward to press her cheek to his. “We’ll see you tomorrow evening,” she told him. “Don’t forget you promised to come to our house for supper.”

“I remember.”

He lifted his windbreaker from the back of his chair and started to put it on. Then he paused and looked at Denny. “Say,” he said. “That guy with the French horn, was that your doing?”

Denny said, “What?”

“Did you arrange it? I can just about picture it. Paying a guy good money, even, just so we’d all start missing you.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Red gave a shake of his head and said, “Right.” He chuckled at himself. “That would be too crazy,” he said. He shrugged into his windbreaker and settled the collar. “Still, though,” he said. “How many guys in tank tops listen to classical music?”

Denny looked questioningly at Jeannie, but she was ignoring him. “Got everything, Dad?” she asked.

“Well, no,” he said. “But the others are going to bring it, I guess.” Then he walked over to Denny and set a palm on his back in a gesture that was halfway between a clap and a hug. “Have a good trip, son.”

“Thanks,” Denny said. “I hope the new apartment works out.”

“Yeah, me too.”

Red turned from Denny and left the dining room, with Jeannie and Nora trailing behind. Denny picked up the bag at his feet and followed.

“See you in a while,” Red told the two Hughs in the front hall. They were just coming in for another load, both of them slightly winded.

Jeannie’s Hugh asked Jeannie, “Are you leaving now? I think we can maybe fit one more box in.”

“Never mind that; just put it on the truck,” she said. “I want to get going.” And she shouldered past him and hurried to catch up with Red, as if she feared he might try to escape. They threaded between the tied-back swags of cheesecloth on the porch; Stem stood aside to let them pass. “We should be over there in an hour or so,” he told Red. Red didn’t answer.

At the bottom of the steps, Red paused and looked back at the house. “It wasn’t a dream per se, as a matter of fact,” he told Jeannie.

“What’s that, Dad?”

“When I had that dream the house burned down, it wasn’t an actual dream dream. It was more like one of those pictures you get in your head when you’re half asleep. I was lying in bed and it came to me, kind of – the burnt-out bones of the house. But then I thought, ‘No, no, no, put that out of your mind,’ I thought. ‘It will do okay without us.’ ”

“It will do just fine,” Jeannie said.

He turned and set off down the flagstone walk, then, but Jeannie waited for Denny and Nora, and when they had caught up she reached across Denny’s burden of bags to give him a hug. “Say goodbye to the house,” she told him.

“Bye, house,” he said.

“The last time I missed church, I was in the hospital having Petey,” Nora told Denny as she was driving.

“So, does this mean you’re going to hell?”

“No,” she said in all seriousness. “But it does feel odd.” She flicked on her turn signal. “Maybe I’ll try to make the evening prayer service, if we’re finished moving in by then.”

Denny was gazing out his side window, watching the houses slide past. His left hand, resting on his knee, kept tapping out some private rhythm.

“I guess you’ll be glad to get back to your teaching,” she said after a silence.

He said, “Hmm?” Then he said, “Sure.”

“Will you always just substitute, or do you want a permanent position someday?”

“Oh, for that I’d have to take more course work,” he said. He seemed to have his mind elsewhere.

“I can imagine you’d be really good with high-school kids.”

He swung his eyes toward her. “No,” he said, “the whole thing got me down, it turns out. It was kind of depressing. Everything you’re supposed to teach them, you know it’s only a drop in the bucket – and not all that useful for real life anyhow, most of the time. I’m thinking I might try something else now.”

“Like what?”

“Well, I was thinking of making furniture.”

“Furniture,” she said, as if testing the word.

“I mean, work that would give me something … visible, right? To show at the end of the day. And why fight it: I come from people who build things.”

Nora nodded, just to herself, and Denny returned to looking out his side window. “That thing about the French horn,” he said to a passing bus. “What was that, do you know?”

Nora said, “I have no idea.”

“I hope he’s not losing it.”

“He’ll be all right,” Nora said. “We’ll make sure to keep an eye on him.”

They had reached the top of St. Paul Street now. It would be a straight shot south to Penn Station. Nora sat back in her seat, her fingers loose on the bottom of the wheel. Even driving, she gave the impression of floating. She said, “I would just like to say, Denny – Douglas and I would both like to say – that we appreciate your coming to help out. It meant a lot to your mom and dad. I hope you know that.”

He looked her way again. “Thanks,” he said. “I mean, you’re welcome. Well, thank you both, too.”

“And it was nice of you not to tell about his mother.”

“Oh, well, it’s nobody’s business, really.”

“Not to tell Douglas, I mean. When he was younger.”

“Oh.”

There was another silence.

“You know what happened?” he asked suddenly. There was something startled in his tone, as if he hadn’t intended to speak until that instant. “You know when I was mending Dad’s shirt?”

“Yes.”

“His dashiki kind of thing?”

“Yes, I remember.”

“I was thinking I would never find the right shade of blue, because it was such a bright blue. But I went to the linen closet where Mom always kept her sewing box, and I opened the door, and before I could even reach for the box this spool of bright-blue thread rolled out from the rear of the shelf. I just cupped my hand beneath the shelf and this spool of thread dropped into it.”

They were stopped for a red light now. Nora sent him a thoughtful, remote look.

“Well, of course that can be explained,” he said. “First of all, Mom would have that shade, because she was the one who had made the dashiki in the first place, and you don’t toss a spool of thread just because it’s old. As for why it was out of the box like that … well, I did spill a bunch of stuff out earlier when I was sewing on a button. And I guess the rolling had to do with how I opened the closet door. I set up a whoosh of air or something; I don’t know.”

The light turned green, and Nora resumed driving.

“But in the split second before I realized that,” he said, “I almost imagined that she was handing it to me. Like some kind of, like, secret sign. Stupid, right?”

Nora said, “No.”

“I thought, ‘It’s like she’s telling me she forgives me,’ ” Denny said. “And then I took the dashiki to my room and I sat down on my bed to mend it, and out of nowhere this other thought came. I thought, ‘Or she’s telling me she knows that I forgive her.’ And all at once I got this huge, like, feeling of relief.”

Nora nodded and signaled for a turn.

“Oh, well, who can figure these things?” Denny asked the row houses slipping past.

“I think you’ve figured it just right,” Nora told him.

She turned into Penn Station.

In the passenger drop-off lane, she shifted into park and popped her trunk. “Don’t forget to keep in touch,” she told him.

“Oh, sure. I’d never just disappear; they need me around for the drama.”

She smiled; her two dimples deepened. “They probably do,” she said. “I really think they do.” And she accepted his peck on her cheek and then gave him a languid wave as he stepped out of the car.

The clouds overhead were a deep gray now, churning like muddy waters stirred up from the bottom of a lake, and inside the station, the skylight – ordinarily a kaleidoscope of pale, translucent aquas – had an opaque look. Denny bypassed the ticket machines, which had lines that wound back through the lobby, and went to stand in the line for the agents. Even there some ten or twelve people were waiting ahead of him, so he set down his bags and shoved them along with his foot as the line progressed. He could sense the anxiety of the crowd. A middle-aged couple standing behind him had apparently not thought to reserve, and the wife kept saying, “Oh, God, oh, God, they’re not going to have any seats left, are they?”

“Sure they are,” her husband told her. “Quit your fussing.”

“I knew we should have called ahead. Everybody’s trying to beat the hurricane.”

“Hurkeen,” she pronounced it. She had a wiry, elastic Baltimore accent and a smoker’s rusty voice.

“If there’s not any seats for this one we’ll catch the next one,” her husband told her.

“Next one! Watch there not be a next one. They’ll stop running them after this one.”

The husband made an exasperated huffing sound, but Denny sympathized with the wife. Even with his own reserved seat, he didn’t feel entirely confident. What if they shut down the trains before his train arrived? What if he had to turn around and go back to Bouton Road? Stuck in his family, trapped. Ingrown, like a toenail.

The man in front of him was called to a window, and Denny shoved his bags farther up. He was going to get the elderly agent with the disapproving face; he just knew it. “Sorry, sir …” the agent would say, not sounding sorry in the least.

But no, he got the cheery-looking African-American lady, and her first words when he gave her his confirmation number were “Aren’t you the lucky one!” He signed for his ticket gladly, without his usual muttering at the price. He thanked her and lugged his bags to the Dunkin’ Donuts to buy coffee and, on second thought, a pastry as well, to celebrate. He was going to make it out of here after all.

The few tables outside the Dunkin’ Donuts were occupied, and so were all the benches in the waiting room. He had to eat standing against a pillar with his bags piled at his feet. More passengers were milling around than at Christmas or Thanksgiving, even, all wearing frazzled expressions. “No, you can’t buy a candy bar,” a mother snapped at her little boy. “Stick close to me or you’ll get lost.”

A mellifluous female voice on the loudspeaker announced the arrival of a southbound train at gate B. “That’s B as in Bubba,” the voice said, which Denny found slightly odd. So did the young woman next to him, apparently – an attractive redhead with that golden tan skin that was always such an unexpected pleasure to see in a redhead. She quirked her eyebrows at him, inviting him to share her amusement.

Sometimes you glance toward a woman and she glances toward you and there is this subtle recognition, this moment of complicity, and anything might happen after that. Or not. Denny turned away and dropped his paper cup in the waste bin.

The train at gate B-for-Bubba was traveling to D.C., where nobody seemed to want to go, but when Denny’s northbound train was announced there was a general surge toward the stairs. Denny thought of what Jeannie’s Hugh had said the night before; shouldn’t all these people be heading away from the hurricane? But north was where home was, he’d be willing to bet – drawing them irresistibly, as if they were migratory birds. They pressed him forward, down the stairs, and when he reached the platform he felt a twinge of vertigo as they steered him too close to the tracks. He pulled ahead, making his way to where the forward cars would board. But he didn’t want the quiet car. Quiet cars made him edgy. He liked to sit surrounded by a sea of anonymous chatter; he liked the living-room-like coziness of mixed and mingled cell-phone conversations.

The train curved toward them from a distance, almost the same shade of gray as the darkened air it moved through, and a number of cars flashed past before it shrieked to a stop. There didn’t appear to be a quiet car, as far as Denny could tell. He boarded through the nearest door and chose the first empty seat, next to a teenage boy in a leather jacket, because he knew he had no hope of sitting by himself. First he heaved his luggage into the overhead rack, and only then did he ask, “This seat taken?” The boy shrugged and looked away from him, out the window. Denny dropped into his seat and slipped his ticket from his inside breast pocket.

Always that “Ahh” feeling when you settle into place, finally. Always followed, in a matter of minutes, by “How soon can I get out of here?” But for now, he felt completely, gratefully at rest.

People were having trouble finding seats. They were jamming the aisle, bumbling past with their knobby backpacks, calling to each other in frantic-sounding voices. “Dina? Where’d you go?” “Over here, Mom.” “There’s room up ahead, folks!” a conductor shouted from the forward end.

The train started moving, and those who were still standing lurched and grabbed for support. A woman arguably old enough to be offered a seat loomed above Denny for a full minute, and he studied his ticket with deep concentration till another woman called to her and she moved away.

Row houses passed in a slow, dismal stream – their rear windows drably curtained or blanked out with curling paper shades, their back porches crammed with barbecue grills and garbage cans, their yards a jumble of rusty cast-off appliances. Inside the car, the hubbub gradually settled down. Denny’s seatmate leaned his head against the window and stared out. As imperceptibly as possible, Denny slid his phone from his pocket. He hit the memory dial and then bent forward till he was almost doubled up. He didn’t want this conversation overheard.

“Hey, there. It’s Alison,” the recording said. “I’m either out or unavailable, but you can always leave me a message.”

“Pick up, Allie,” he said. “It’s me.”

There was a pause, and then a click.

“You act like saying ‘It’s me’ will make me drop everything and come running,” she said.

Another time, he might have asked, “And didn’t it?” Three months ago he might have asked that. But now he said, “Well, a guy can always hope.”

She said nothing.

“What’re you up to?” he asked finally.

“I’m trying to get ready for Sandy.”

“Who’s Sandy?”

“What is Sandy, idiot. Sandy the hurricane; where have you been?”

“Ah.”

“On the news they’re showing people laying sandbags across their doorways, but where on earth do you buy those?”

“I’ll see to that,” he told her. “I’m already on the train.”

Another pause, during which he held very still. But in the end, all she said was “Denny.”

“What.”

“I have not said yes to that yet.”

“I realize you haven’t,” he said. He said it a bit too quickly, so she wouldn’t retract the word “yet.” “But I’m hoping that the sight of my irresistible self will work its magic.”

“Is that right,” she said flatly.

He squinched his eyes almost shut, and waited.

“We’ve already talked about this,” she told him. “Nothing’s changed. No way am I going to let things go on like they were before.”

“I know that.”

“I’m tired. I’m worn out. I’m thirty-three years old.”

The conductor was standing over him. Denny sat up straight and thrust his ticket at him blindly.

“I need somebody I can depend on,” she said. “I need a guy who won’t change jobs more often than most people change gym memberships, or take off on a road trip without any notice, or sit around all day in sweat pants smoking weed. And most of all, someone who’s not moody, moody, moody. Just moody for no reason! Moody!”

Denny leaned forward again.

“Listen,” he said. “Allie. You’re always asking what on earth is wrong with me, but don’t you think I wonder too? I’ve been asking it all my life; I wake up in the middle of the night and I ask, ‘What’s the matter with me? How could I screw up like this?’ I look at how I act sometimes and I just can’t explain it.”

The silence at the other end was so profound that he wondered if she had hung up. He said, “Al?”

“What.”

“Are you there?”

“I’m here.”

He said, “My dad says he remembers my mom’s gone even while he’s asleep.”

“That’s sad,” Allie said after a moment.

“But I do, too,” he said. “I remember you’re gone, every second I’ve been away.”

All he heard was silence.

“So I want to come back,” he said. “I want to do things differently this time.”

More silence.

“Allie?”

“Well,” she said, “we could take it day by day, I guess.”

He let out his breath. He said, “You won’t regret it.”

“I probably will, in fact.”

“You won’t, I swear to God.”

“But this is a trial run, understand? You’re only here on approval.”

“Absolutely. No question,” he said. “You can kick me out the first mistake I make.”

“Oh, Lord. I don’t know why I’m such a pushover.”

He said, “Are my things still in your garage?”

“They were the last time I looked.”

“So … I can move them back into the house?”

When she didn’t answer immediately, he took a tighter grip on the phone. “I’m not saying I have to,” he said. “I mean, if you tell me I have to live above the garage again, just to start with, I would understand.”

Allie said, “Well, I don’t know that we would need to go that far.”

He relaxed his grip on the phone.

The two young girls just behind him could not stop laughing. They kept dissolving in cascades of giggles, sputtering and squeaking. What did girls that age find so funny? The other passengers were reading, or listening to their music, or typing away on their computers, but these two were saying “Oh, oh, oh” and gasping for breath and then going off in more gales of laughter.

Denny glanced toward his seatmate, half expecting to exchange a look of bafflement, but to his horror, he discovered that the boy was crying. He wasn’t just teary; he was shaking with sobs, his mouth stretched wide in agony, his hands convulsively clutching his kneecaps. Denny couldn’t think what to do. Offer sympathy? Ignore him? But ignoring him seemed callous. And when someone showed his grief so openly, wasn’t he asking for help? Denny looked around, but none of the other passengers seemed aware of the situation. He transferred his gaze to the seat back in front of him and willed the moment to pass.

It was like when Stem first came to stay, when he slept in Denny’s room and cried himself to sleep every night and Denny lay silent and rigid, staring up at the dark, trying not to hear.

Or like when he himself, years later in boarding school, longed all day for bedtime just so he could let the tears slide secretly down the sides of his face to his pillow, although not for any good reason, because God knows he was glad to get away from his family and they were glad to see him go. Thank heaven the other boys never realized.

It was this last thought that told him what to do about his seatmate: nothing. Pretend not to notice. Look past him out the rain-spattered window. Focus purely on the scenery, which had changed to open countryside now, leaving behind the blighted row houses, leaving behind the station under its weight of roiling dark clouds, and the empty city streets around it, and the narrower streets farther north with the trees turning inside out in the wind, and the house on Bouton Road where the filmy-skirted ghosts frolicked and danced on the porch with nobody left to watch.