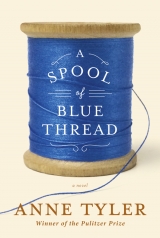

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Red had started noticing that any time it was a girls-only gathering, Pookie had a tendency to speak of Trey belittlingly. She mocked the loving care he gave to the sheet of blond hair that fell over his forehead, and she referred to him habitually as “the Prince of Roland Park.” “I can’t come shopping tomorrow,” she’d say, “because the Prince of Roland Park wants me to go to lunch with his mother.” Partly, this could be explained by the fact that her crowd liked to affect a tone of ironic amusement no matter what they were discussing. But also, Trey sort of deserved the title. Even during high school he had driven a sports car, and the Barristers’ house in Baltimore was only one of three that they owned, the others in distant resorts that advertised in the New York Times. Pookie said he was spoiled rotten, and she blamed it on his mother, “Queen Eula.”

Eula Barrister was stick-thin and fashionable and discontented-looking. Any time Red saw her in church, he was reminded of Mrs. Brill. Mrs. Barrister ran that church, and she ran the Women’s Club, and she ran her family, which consisted of just three people. Trey was her only child – her darlin’ boy, she was fond of saying; her poppet. And Pookie Vanderlin was nowhere near good enough for him.

Over the course of the summer, Red heard long recitals of Pookie’s tribulations with Queen Eula. Pookie was summoned to excruciating family dinners, to stiff old-lady teas, to Queen Eula’s own beautician to do something about her eyebrows. She was chided for her failure to write bread-and-butter notes, or for writing bread-and-butter notes that weren’t enthusiastic enough. Her choice of silver pattern was reversed without her say-so. She was urged to consider a wedding gown that would hide her chubby shoulders.

Over and over, Merrick gasped, like somebody on stage. “No! I can’t believe it!” she would say. “Why doesn’t Trey stick up for you?”

“Oh, Trey,” Pookie said in disgust. “Trey thinks she hung the moon.”

Not only that: Trey was inconsiderate, and selfish, and given to hypochondria. He forgot Pookie existed any time he ran into his buddies. And for once, just once in her life, she would like to see him make it through an evening without drinking his weight in gin.

“He’d better watch out, or he’ll lose you,” Merrick said. “You could have anyone! You don’t have to settle for Trey. Look at Tucky Bennett: he just about shot himself when he heard you’d gotten engaged.”

Often, Pookie delivered her recitals even though Red was present. (Red didn’t count, in that group.) Then Red would ask, “How come you put up with it?” Or “You said yes to this guy?”

“I know. I’m a fool,” she would say. But not as if she meant it.

That fall, when they were all back in college, Merrick fell into a pattern of coming home every weekend. This was unlike her. Red came home a lot himself, since College Park was so close, but gradually he realized that she was there even more often. She went with the family to church on Sunday, and afterwards she would stop out front to say hello to Eula Barrister. Even when Trey was not standing at his mother’s elbow (which generally he was), Merrick would be eagerly nodding her head in her demure new pillbox hat, giving a liquid laugh that any brother would know to be false, hanging on to every one of Eula Barrister’s prune-faced remarks. And in the evening, if Trey stopped by for a visit – as was only natural! Merrick said. He was marrying her best friend, after all! – the two of them sat out on the porch, although it was too cold for that now. The smell of their cigarette smoke floated through Red’s open window. (But if it was so cold, his children would wonder years later, why was his window open?) “I’ve had it with her. I tell you,” Trey said. “Nothing I do makes her happy. Everything’s pick, pick, pick.”

“She doesn’t properly value you, it sounds like to me,” Merrick said.

“And you should see how she acts with Mother. She claimed she couldn’t help Mother sample the rehearsal-dinner menus because she had a term paper due. A term paper! When it’s her wedding!”

“Oh, your poor mother,” Merrick said. “She was only trying to make her feel included.”

“How come you understand that, Bean, and Pookie doesn’t?”

Red slammed his window shut.

Junior told Red he was imagining things. After the situation blew up, after the truth came bursting out and nearly all of Baltimore stopped speaking to Trey and Merrick, Red said, “I knew this would happen! I saw it coming. Merrick planned it from the start; she stole him.”

But Junior said, “Boy, what are you talking about? Human beings can’t be stolen. Not unless they want to be.”

“I swear, she started plotting last summer and damned if she didn’t go through with it. She flattered Trey to his face and she ran him down to Pookie behind his back and she curtsied and kowtowed to his mother till I thought I was going to puke.”

“Well, it’s not like he was Pookie’s property,” Junior said.

Then he said, “And anyhow, he’s Merrick’s now.”

And two lines deepened at the corners of his mouth, the way they always did when he had settled some piece of business exactly to his liking.

An outside observer might say that these weren’t stories at all. Somebody buys a house he’s admired when it finally comes on the market. Somebody marries a man who was once engaged to her friend. It happens all the time.

Maybe it was just that the Whitshanks were such a recent family, so short on family history. They didn’t have that many stories to choose from. They had to make the most of what they could get.

Clearly they couldn’t look to Red for stories. Red just went ahead and married Abby Dalton, whom he had known since she was twelve – a Hampden girl, coincidentally, from the neighborhood where the Whitshanks used to live. In fact, he and she lived in Hampden themselves, during the early days of their marriage. (“Why’d we even bother moving,” his father asked him, “if you were going to head back down there the very first chance you got?”) Then after his parents died – killed by a freight train in ’67 when their car stalled on the railroad tracks – Red took over the house on Bouton Road. Certainly Merrick didn’t want it. She and Trey had a much better place of their own, not to mention their Sarasota property, and besides, she said, she had never really liked that house. It didn’t have en suite bathrooms, and when Junior had finally added one to the master bedroom, reconfiguring the giant cedar-lined storeroom back in the 1950s, she’d complained that she was jolted awake every time the toilet flushed. So there Red was, in the house he’d grown up in, where he planned to die one day. Not much of a story in that.

The neighborhood referred to it as “the Whitshank house” now. Junior would have been happy to know that. One of his major annoyances was that from time to time he’d been introduced as “Mr. Whitshank, who lives in the Brill house.”

There was nothing remarkable about the Whitshanks. None of them was famous. None of them could claim exceptional intelligence. And in looks, they were no more than average. Their leanness was the rawboned kind, not the lithe, elastic slenderness of people in magazine ads, and something a little too sharp in their faces suggested that while they themselves were eating just fine, perhaps their forefathers had not. As they aged, they developed sagging folds beneath their eyes, which anyway drooped at the outer corners, giving them a faintly sorrowful expression.

Their family firm was well thought of, but then so were many others, and the low number on their home-improvement license testified to nothing more than mere longevity, so why make such a fuss about it? Staying put: they appeared to view it as a virtue. Three of Red and Abby’s four children lived within twenty minutes of them. Nothing so notable about that!

But like most families, they imagined they were special. They took great pride, for instance, in their fix-it skills. Calling in a repairman – even one of their own employees – was looked upon as a sign of defeat. All of them had inherited Junior’s allergy to ostentation, and all of them were convinced that they had better taste than the rest of the world. At times they made a little too much of the family quirks – of both Amanda and Jeannie marrying men named Hugh, for instance, so that their husbands were referred to as “Amanda’s Hugh” and “Jeannie’s Hugh”; or their genetic predisposition for lying awake two hours in the middle of every night; or their uncanny ability to keep their dogs alive for eons. With the exception of Amanda they paid far too little attention to what clothes they put on in the morning, and yet they fiercely disapproved of any adult they saw wearing blue jeans. They shifted uneasily in their chairs during any talk of religion. They liked to say that they didn’t care for sweets, although there was some evidence that they weren’t as averse as they claimed. To varying degrees they tolerated each other’s spouses, but they made no particular effort with the spouses’ families, whom they generally felt to be not quite as close and kindred-spirited as their own family was. And they spoke with the unhurried drawl of people who work with their hands, even though not all of them did work with their hands. This gave them an air of good-natured patience that was not entirely deserved.

Patience, in fact, was what the Whitshanks imagined to be the theme of their two stories – patiently lying in wait for what they believed should come to them. “Biding their time,” as Junior had put it, and as Merrick might have put it too if she had been willing to talk about it. But somebody more critical might say that the theme was envy. And someone else, someone who had known the family intimately and forever (but there wasn’t any such person), might ask why no one seemed to realize that another, unspoken theme lay beneath the first two: in the long run, both stories had led to disappointment.

Junior got his house, but it didn’t seem to make him as happy as you might expect, and he had often been seen contemplating it with a puzzled, forlorn sort of look on his face. He spent the rest of his life fidgeting with it, altering it, adding closets, resetting flagstones, as if he hoped that achieving the perfect abode would finally open the hearts of those neighbors who never acknowledged him. Neighbors whom he didn’t even like, as it turned out.

Merrick got her husband, but he was a cold, aloof man unless he was drinking, in which case he grew argumentative and boorish. They never had children, and Merrick spent most of her time alone in the Sarasota place so as to avoid her mother-in-law, whom she detested.

The disappointments seemed to escape the family’s notice, though. That was another of their quirks: they had a talent for pretending that everything was fine. Or maybe it wasn’t a quirk at all. Maybe it was just further proof that the Whitshanks were not remarkable in any way whatsoever.

3

ON THE VERY FIRST DAY OF 2012, Abby began disappearing.

She and Red had kept Stem’s three boys overnight so that Stem and Nora could go to a New Year’s Eve party, and Stem showed up to collect them around ten o’clock the next morning. Like everyone else in the family, he gave only a token knock before walking on into the house. “Hello?” he called. He stopped in the hall and stood listening, idly ruffling the dog’s ears. The only sounds came from his children in the sunroom. “Hello,” he said again. He walked toward their voices.

The boys sat on the rug around a Parcheesi board, three stair-step towheads dressed scruffily in jeans. “Dad,” Petey said, “tell Sammy he can’t play with us. He doesn’t add the dots up right!”

“Where’s your grandma?” Stem asked.

“I don’t know. Tell him, Dad! And he rolled the dice so hard, one went under the couch.”

“Grandma said I could play,” Sammy said.

Stem walked back into the living room. “Mom? Dad?” he called.

No answer.

He went to the kitchen, where he found his father sitting at the breakfast table reading the Baltimore Sun. Over the past few years Red had grown hard of hearing, and it wasn’t till Stem entered his line of vision that he looked up from his newspaper. “Hey!” he said. “Happy New Year!”

“Happy New Year to you.”

“How was the party?”

“It was good. Where’s Mom?”

“Oh, somewhere around. Want some coffee?”

“No, thanks.”

“I just made it.”

“I’m okay.”

Stem walked over to the back door and looked out. A lone cardinal sat in the nearest dogwood, bright as a leftover leaf, but otherwise the yard was empty. He turned away. “I’m thinking we’ll have to fire Guillermo,” he said.

“Pardon?”

“Guillermo. We should get rid of him. De’Ontay said he showed up hungover again on Friday.”

Red made a clucking sound and folded his newspaper. “Well, it’s not like there aren’t plenty of other guys out there nowadays,” he said.

“Kids behave okay?”

“Yes, fine.”

“Thanks for looking after them. I’ll go get their stuff together.”

Stem went back into the hall, climbed the stairs, and headed toward the bedroom that used to be his sisters’. It was full of bunk beds now, and the floor was a welter of tossed-off pajamas and comic books and backpacks. He began stuffing any clothing he found into the backpacks, taking no particular notice of what belonged to which child. Then, with the backpacks slung over one shoulder, he stepped into the hall again. He called, “Mom?”

He looked into his parents’ bedroom. No Abby. The bed was neatly made and the bathroom door stood open, as did the doors of all the rooms lining the U-shaped hall – Denny’s old room, which now served as Abby’s study, and the children’s bathroom and the room that used to be his. He hoisted the backpacks higher on his shoulder and went downstairs.

In the sunroom, he told the boys, “Okay, guys, get a move on. You need to find your jackets. Sammy, where are your shoes?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, look for them,” he said.

He went back to the kitchen. Red was standing at the counter, pouring another cup of coffee. “We’re off, Dad,” Stem told him. His father gave no sign he had heard him. “Dad?” Stem said.

Red turned.

“We’re leaving now,” Stem said.

“Oh! Well, tell Nora Happy New Year.”

“And you thank Mom for us, okay? Do you think she’s running an errand?”

“Married?”

“Errand. Could she be out running an errand?”

“Oh, no. She doesn’t drive anymore.”

“She doesn’t?” Stem stared at him. “But she was driving just last week,” he said.

“No, she wasn’t.”

“She drove Petey to his play date.”

“That was a month ago, at least. Now she doesn’t drive anymore.”

“Why not?” Stem asked.

Red shrugged.

“Did something happen?”

“I think something happened,” Red said.

Stem set the boys’ backpacks on the breakfast table. “Like what?” he asked.

“She wouldn’t say. Well, not like an accident or anything. The car looked fine. But she came home and said she’d given up driving.”

“Came home from where?” Stem asked.

“From driving Petey to his play date.”

“Jeez,” Stem said.

He and Red looked at each other for a moment.

“I was thinking we ought to sell her car,” Red said, “but that would leave us with just my pickup. Besides, what if she changes her mind, you know?”

“Better she doesn’t change her mind, if something happened,” Stem said.

“Well, it’s not as if she’s old. Just seventy-two next week! How’s she going to get around all the rest of her life?”

Stem crossed the kitchen and opened the door to the basement. It was obvious no one was down there – the lights were off – but still he called, “Mom?”

Silence.

He closed the door and headed back to the sunroom, with Red following close behind. “Guys,” Stem said. “I need to know where your grandma is.”

The boys were just as he’d left them – sprawled around the Parcheesi board, jackets not on, Sammy still in his socks. They looked up at him blankly.

“She was here when you came downstairs, right?” Stem asked. “She fixed you breakfast.”

“We haven’t had any breakfast,” Tommy told him.

“She didn’t fix you breakfast?”

“She asked did we want cereal or toast and then she went away to the kitchen.”

Sammy said, “I never, ever get the Froot Loops. There is only two in the pack and Petey and Tommy always get them.”

“That’s because me and Tommy are the oldest,” Petey said.

“It’s not fair, Daddy.”

Stem turned to Red and found him staring at him intently, as if waiting for a translation. “She wasn’t here for breakfast,” Stem told him.

“Let’s check upstairs.”

“I did check upstairs.”

But they headed for the stairs anyway, like people hunting their keys in the same place over and over because they can’t believe that isn’t where they are. At the top of the stairs, they walked into the children’s bathroom – a chaotic scene of crumpled towels, toothpaste squiggles, plastic boats on their sides in the bottom of the tub. They walked out again and into Abby’s study. They found her sitting on the daybed, fully dressed and wearing an apron. She wasn’t visible from the hall, but she surely must have heard Stem calling. The dog was stretched out on the rug at her feet. When the men walked in, both Abby and the dog glanced up and Abby said, “Oh, hello there.”

“Mom? We’ve been looking for you everywhere,” Stem said.

“I’m sorry. How was the party?”

“The party was fine,” Stem said. “Didn’t you hear us calling?”

“No, I guess I didn’t. I’m so sorry!”

Red was breathing heavily. Stem turned and looked at him. Red passed a hand over his face and said, “Hon.”

“What,” Abby said, and there was something a little too bright in her voice.

“You had us worried there, hon.”

“Oh, how ridiculous!” Abby said. She smoothed her apron across her lap.

This room had become her work space as soon as Denny was gone for good – a retreat where she could go over any clients’ files she’d brought home with her, or talk with them on the phone. Even after her retirement, she continued to come here to read, or write poems, or just spend time by herself. The built-in cabinets that used to hold Linnie’s sewing supplies were stuffed with Abby’s journals and random clippings and handmade cards from when the children were small. One wall was so closely hung with family photographs that there was no space visible between one frame and the next. “How can you see them that way?” Amanda had asked once. “How can you really look at them?” But Abby said blithely, “Oh, I don’t have to,” which made no sense whatsoever.

Ordinarily she sat at the desk beneath the window. No one had ever known her to sit on the daybed, which was intended merely to accommodate any excess of overnight guests. There was something contrived and stagey in her posture, as if she had hastily scrambled into place when she heard their steps on the stairs. She gazed up at them with a bland, opaque smile, her face oddly free of smile lines.

“Well,” Stem said, and he exchanged a look with his father, and the subject was dropped.

What you do on New Year’s you’ll be doing all year long, people claim, and certainly Abby’s disappearance set the theme for 2012. She began to go away, somehow, even when she was present. She seemed to be partly missing from many of the conversations taking place around her. Amanda said she acted like a woman who’d fallen in love, but quite apart from the fact that Abby had always and forever loved only Red, so far as they knew, she lacked that air of giddy happiness that comes with falling in love. She actually seemed unhappy, which wasn’t like her in the least. She took on a fretful expression, and her hair – gray now and chopped level with her jaw, as thick and bushy as the wig on an old china doll – developed a frazzled look, as if she had just emerged from some distressing misadventure.

Stem and Nora asked Petey what had happened on the ride to his play date, but first he didn’t know what play date they were talking about and then he said the ride had gone fine. So Amanda confronted Abby straight on; said, “I hear you’re not driving these days.” Yes, Abby said, that was her little gift to herself: never to have to drive anyplace ever again. And she gave Amanda one of her new, bland smiles. “Back off,” that smile said. And “Wrong? Why would you think anything was wrong?”

In February, she threw her idea box away. This was an Easy Spirit shoe box that she had kept for decades, crammed with torn-off bits of paper she meant to turn into poems one day. She put it out with the recycling on a very windy evening, and by morning the bits of paper were lying all over the street. Neighbors kept finding them in their hedges and on their welcome mats—“moon like a soft-boiled egg yolk” and “heart like a water balloon.” There was no question as to their source. Everyone knew about Abby’s poems, not to mention her fondness for similes. Most people just tactfully discarded them, but Marge Ellis brought a whole handful to the Whitshanks’ front door, where Red accepted them with a confused look on his face. “Abby?” he said later. “Did you mean to throw these out?”

“I’m done with writing poems,” she said.

“But I liked your poems!”

“Did you?” she asked without interest. “That’s nice.”

It was probably more the idea Red liked – his wife the poet, scribbling away at her antique desk that he’d had one of his workmen refinish, sending her efforts to tiny magazines that promptly sent them back. But even so, Red began to wear the same unhappy expression that Abby wore.

In April, her children noticed that she’d started calling the dog “Clarence,” although Clarence had died years ago and Brenda was a whole different color, golden retriever instead of black Lab. This was not Abby’s usual absentminded roster of misnomers: “Mandy – I mean Stem” when she was speaking to Jeannie. No, this time she stuck with the wrong name, as if she were hoping to summon back the dog of her younger days. Poor Brenda, bless her heart, didn’t know what to make of it. She’d give a puzzled twitch of her pale sprouty eyebrows and fail to respond, and Abby would cluck in exasperation.

It wasn’t Alzheimer’s. (Was it?) She seemed too much in touch for Alzheimer’s. And she didn’t exhibit any specific physical symptoms they could tell a doctor about, like seizures or fainting fits. Not that they had much hope of persuading her to see a doctor, anyhow. She’d fired her internist at age sixty, claiming she was too old now for any “extreme measures,” and for all they knew he wasn’t even in practice anymore. But even if he were: “Is she forgetful?” he might ask, and they would have to say, “Well, no more than usual.”

“Is she illogical?”

“Well, no more than …”

There you had the problem: Abby’s “usual” was fairly scatty. Who could say how much of this behavior was simply Abby being Abby?

As a girl, she’d been a fey sprite of a thing. She’d worn black turtlenecks in winter and peasant blouses in summer; her hair had hung long and straight down her back while most girls clamped their pageboys into rollers every night. She wasn’t just poetic but artistic, too, and a modern dancer, and an activist for any worthy cause that came along. You could count on her to organize her school’s Canned Goods for the Poor drive and the Mitten Tree. Her school was Merrick’s school, private and girls-only and posh, and though Abby was only a scholarship student, she was the star there, the leader. In college, she plaited her hair into cornrows and picketed for civil rights. She graduated near the top of her class and became a social worker, what a surprise, venturing into Baltimore neighborhoods that none of her old schoolmates knew existed. Even after she married Red (whom she had known for so long that neither of them could remember their first meeting), did she turn ordinary? Not a chance. She insisted on natural childbirth, breast-fed her babies in public, served her family wheat germ and home-brewed yogurt, marched against the Vietnam War with her youngest astride her hip, sent her children to public schools. Her house was filled with her handicrafts – macramé plant hangers and colorful woven serapes. She took in strangers off the streets, and some of them stayed for weeks. There was no telling who would show up at her dinner table.

Old Junior thought Red had married her to spite him. This was not true, of course. Red loved her for her own sake, plain and simple. Linnie Mae adored her, and Abby adored her back. Merrick was appalled by her. Merrick had been forced to serve as Abby’s Big Sister back when Abby had first transferred to her school. Even then she had felt that Abby was beyond hope of rescue, and time had proven her right.

As for Abby’s children, well, naturally they loved her. It was assumed that even Denny loved her, in his way. But she was a dreadful embarrassment to them. During visits from their friends, for instance, she might charge into the room declaiming a poem she’d just written. She might buttonhole the mailman to let him know why she believed in reincarnation. (“Mozart” was the reason she gave. How could you hear a composition from Mozart’s childhood and not feel sure that he had been drawing on several lifetimes’ worth of experience?) Encountering anyone with even a hint of a foreign accent, she would seize his hand and gaze into his eyes and say, “Tell me. Where is home, for you?”

“Mom!” her children protested afterward, and she would say, “What? What’d I do wrong?”

“It’s none of your business, Mom! He was hoping you wouldn’t notice! He was probably imagining you couldn’t even guess he was foreign.”

“Nonsense. He should be proud to be foreign. I know I would be.”

In unison, her children would groan.

She was so intrusive, so sure of her welcome, so utterly lacking in self-consciousness. She assumed she had the right to ask them any questions she liked. She held the wrongheaded notion that if they didn’t want to discuss some intimate personal problem, maybe they would change their minds if she turned the tables on them. (Was this something she’d learned in social work?) “Let’s put this the other way around,” she would say, hunching forward cozily. “Let’s say you advise me. Say I have a boyfriend who’s acting too possessive.” She would give a little laugh. “I’m at my wit’s end!” she would cry. “Tell me what I should do!”

“Really, Mom.”

They had as little contact as possible with her orphans – the army veterans who were having trouble returning to normal life, the nuns who had left their orders, the homesick Chinese students at Hopkins – and they thought Thanksgiving was hell. They snuck white bread into the house, and hot dogs full of nitrites. They cowered when they heard she’d be in charge of their school picnic. And most of all, most emphatically of all, they hated how her favorite means of connecting was commiseration. “Oh, poor you!” she would say. “You’re looking so tired!” Or “You must be feeling so lonely!” Other people showed love by offering compliments; Abby offered pity. It was not an attractive quality, in her children’s opinion.

Yet when she went back to work, after her last child started school, Jeannie told Amanda it wasn’t the relief that she had expected. “I thought I would be glad,” she said, “but then I catch myself wondering, ‘Where’s Mom? Why isn’t she breathing down my neck?’ ”

“You can notice a toothache’s gone too,” Amanda said. “It doesn’t mean you want it back again.”

In May, Red had a heart attack.

It wasn’t a very dramatic one. He experienced a few ambiguous symptoms on a job site, was all, and De’Ontay insisted on driving him to the emergency room. Still, it came as a shock to his family. He was only seventy-four! He had seemed so healthy; he climbed ladders the same as ever and carried heavy loads, and he didn’t weigh a pound more than he had when he’d gotten married. But now Abby wanted him to retire, and both the girls agreed with her. What if he lost consciousness while he was up on a roof? Red said he would go crazy if he retired. Stem said maybe he could keep on working but quit going up on roofs. Denny was not on hand for this discussion, but he most probably would have sided with Stem, for once.

Red prevailed, and he was back on the job shortly after being discharged from the hospital. He looked fine. He did say he felt a bit weak, and he admitted to getting tired earlier in the day. But maybe that was all in his head; he was observed several times taking his own pulse, or laying one palm in a testing way across the center of his chest. “Are you all right?” Abby would ask. He would say, “Of course I’m all right,” in an irritated tone that he had never used in the past.

He had hearing aids now, but he claimed they were no help. Often he just left them sitting on top of his bureau – two pink plastic nubbins the size and shape of chicken hearts. As a result, his conversations with his customers didn’t always go smoothly. More and more, he allowed Stem to deal with that part of the business, although you could tell it made him sad to give it up.

He was letting the house go, too. Stem was the first to notice that. While once upon a time the house was maintained to a fare-thee-well – not a loose nail anywhere, not a chink in the window putty – now there were signs of slippage. Amanda arrived with her daughter one evening and found Stem reinstalling the spline on the front screen door, and when she asked, offhandedly, “Problem?” Stem straightened and said, “He’d never have let this happen in the old days.”

“Let what happen?”

“This screen was bagging halfway out of its frame! And the powder-room faucet is dripping, have you noticed?”

“Oh, dear,” Amanda said, and she prepared to follow Elise on into the house.

But Stem said, “It’s like he’s lost interest,” which stopped her in her tracks.

“Like he doesn’t care, almost,” Stem said. “I said, ‘Dad, your front screen’s loose,’ and he said, ‘I can’t keep on top of every last little thing, goddammit!’ ”

This was huge: for Red to snap at Stem. Stem had always been his favorite.

Amanda said, “Maybe this place is getting to be too much for him.”

“Not only that, but Mom left a kettle on the stove the other day, and when Nora stopped by, the kettle was whistling full-blast and Dad was writing checks at the dining-room table, totally unaware.”