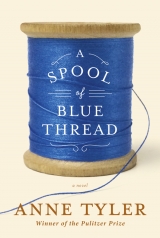

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“Then why—?”

“Let me get this clear,” he told her. “I don’t have a place to live anymore, is that what you’re saying?”

“No, and me neither. Can you believe it? Would you ever think that she could act so ugly? And then I had to carry all those things down the street – my suitcase and that great knobby bundle and your canister with the bread inside and – oh! Junior! Your milk bottle! I forgot your milk bottle! I’m so sorry!”

“That’s what you’re sorry about?”

“I’ll buy us another. Milk was ten cents at this store I went past. I’ve got ten cents, easy.”

“You are telling me I’m sleeping on the street tonight,” Junior said.

“No, wait; I’m getting to that. There I was, toting all our worldly goods, walking down the street and crying, and I was looking for a ROOM TO LET sign but I didn’t see nary a one so finally I just knocked on some lady’s door and said, ‘Please, my husband and I have lost our home and we’ve got no place to stay.’ ”

“Well, that would never work,” Junior said. (He didn’t bother dealing just now with the “husband” part.) “Half the country could say that.”

“You’re right,” Linnie said cheerfully. “It didn’t work a bit, not with her nor with the next lady either nor the lady after that, though all of them were real nice about it. ‘Sorry, honey,’ they said, and one lady offered me a square of gingerbread but I was still full from the charity sandwich. By then I was way down Dutch Street. I’d turned left at the café and of course I didn’t bother asking there, not after how they’d treated me. But the next lady said that she would take us in.”

“What?”

“And it’s a nicer room, too. It’s got a bigger bed, so you won’t have to sleep on a chair. No bureau, but there’s a nightstand with drawers, and a closet. The lady let me have it because her husband’s been laid off work and she’s been thinking for a while now, she said, that maybe their little boy should move in with his sister so they could rent his room out for five dollars a week.”

“Five dollars!” Junior said. “Why so steep?”

“Is that steep?”

“At Mrs. Davies’s I pay four.”

“You do?”

“Is this with meals?” Junior asked.

“Well, no.”

Junior looked longingly toward Mrs. Davies’s house. For one half-second, he contemplated climbing her steps and ringing the doorbell. Maybe he could reason with her. She’d always seemed to like him. She had asked him to call her Bess, even, but that would have felt impertinent; she had to be in her forties. And just this past Christmas Eve she had invited him down to her parlor for a glass of something special (as she called it) that she had bought at the paint store, but that had been sort of uncomfortable because even though Junior missed having people to talk to, somehow with Mrs. Davies he hadn’t been able to think of a single thing to say.

Maybe he could make like he had come to return his key, and then he would happen to mention that he barely knew Linnie Mae (which was true, in fact), that she was nothing to him, merely a girl from home in need of a place to stay, and he had taken pity on her.

But right while he had his eyes on the house, a little gap in the parlor curtain closed with an angry snap, and he knew there was no use trying.

He set off toward the Essex, and Linnie walked beside him with a bounce to each step, almost as if she were skipping. “You’re going to like Cora Lee,” she said. “She comes from West Virginia.”

“Oh, she’s ‘Cora Lee’ already, is she.”

“She thinks we’re just real cute and adventurous to be up here on our own so far away from our families.”

“Linnie Mae,” he said, stopping short on the sidewalk, “how come you claimed I was your husband?”

“Well, what else could I tell people? How would anyone give us a room if they didn’t think we were married? Besides: I feel married. It didn’t even feel like I was telling a story.”

“ ‘Lie’ is what they call it up here,” he told her. “They don’t pussyfoot around calling it a ‘story.’ ”

“Well, I can’t help that. Down home it’s rude to say ‘lie,’ as you very well know your own self.” She gave him a little poke in the ribs, and they started walking again. “Anyhow,” she said, “neither one applies, not ‘lie’ nor ‘story’ neither. I honestly feel like you and I have been husband and wife forever, from a time before we were born, even.”

Junior couldn’t think where to begin to argue with that.

They had reached his car now and he walked around to the driver’s side and got in and started the engine, leaving Linnie Mae to open the passenger door herself. If it weren’t that she was the only one who knew where all his earthly belongings were, he would gladly have left her behind.

The new room was not nicer than the old one. It was even smaller, in a millworker’s squat clapboard house about five blocks south of Mrs. Davies’s. The bed was a single with a sunken-in mattress, admittedly wider than the cot at Mrs. Davies’s but not by much, and there was a water stain on the ceiling near the window. But Cora Lee seemed pleasant enough – a plump, brown-haired woman in her early thirties – and almost her first words as she was showing him the room were, “Now, I want you to tell us if anything’s not right, because we’ve never taken in roomers before and we don’t know just how it’s done.”

“Well,” Junior said, “in the old place, I was paying four dollars. We were paying four dollars.”

But from the way Cora Lee’s face suddenly lurched and froze, he could tell she had set her heart on five. A cannier man might have argued even so, but Junior didn’t have it in him and he changed the subject to the bathroom arrangements. Cora Lee looked happy again. Now that her husband wasn’t working, she said, Junior was welcome to take first turn at the bathroom in the mornings. Linnie, meanwhile, was bustling around needlessly straightening the bedspread. Plainly she found money talk embarrassing.

Once Cora Lee had left them on their own, Linnie came to stand in front of him and wrap her arms around him as if they were honeymooners or something, but he freed himself and went to check the closet. “Where’s my Prince Albert tin?” he asked.

“It’s in with your shaving things.”

He reached down a wrinkled paper bag from the closet shelf. Sure enough, there was the tin, and his roll of bills was still folded inside it. He put it back. “We need to buy something for supper,” he said.

“Oh, I’m taking us out for supper.”

“Out where?”

“Did you see that place on the corner? Sam and David’s Eatery. Cora Lee says it’s clean. Tonight’s special is the meatloaf plate, twenty cents apiece.”

“Forty cents total, that means,” he said. “One of those tall cans of salmon from the grocery store is not but twenty-three cents, and it lasts me half a week.”

Although it wouldn’t last both of them half a week, he realized, and he felt something close to fear at the thought of having to feed two instead of one.

“But I want us to celebrate,” Linnie said. “It’s our first real night together; last night didn’t count. And I want me to be the one that pays.”

He said, “How much money have you got, anyhow?”

“Seven dollars and fifty-eight cents!” Linnie said, as if it were something to brag about.

He sighed. “You’re better off saving it up,” he told her.

“Just this once, Junie? Just on our first night?”

“Could you please not call me Junie?” he said.

But he was already putting his jacket back on.

Out on the street Linnie was jubilant, hanging on to his arm and chattering away as they walked. She said Cora Lee had offered them half a shelf in the icebox. “The refrigerator,” she corrected herself. “They have a Kelvinator. We could keep our milk there and some cheese, and then when I know her better I’ll ask to use her stove one time. I’ll clean up after myself real good so she lets me use it again, and next thing you know it will be like the kitchen’s our own. I know just how to work it.”

Junior could well believe it.

“Also I’m getting a job,” she said. “I’m finding me one tomorrow.”

“Now, how are you going to do that?” Junior asked. “It’s not like a thousand grown men aren’t pounding these same streets hunting any work they can hustle up.”

“Oh, I’ll find something. Just wait.”

He drew away and walked separate from her. He felt he was caught in strands of taffy: pull her off the fingers of one hand and then she was sticking to the other. But he had to play his cards right, because he needed that room she had got them. Assuming he couldn’t somehow persuade Mrs. Davies to take him back.

Sam and David’s was tiny, with its specials listed in whitewash on the steamy front window. The twenty-cent meatloaf plate included bread and string beans. Junior let Linnie tug him inside. There were four small tables and a counter with six stools; Linnie chose a table although Junior would have felt easier at the counter. The customers at the counter were lone men in work clothes, while those at the tables were couples.

“You don’t have to have the meatloaf,” Linnie told him. “You can get something pricier.”

“Meatloaf will be fine.”

A woman in an apron came out and filled their water glasses, and Linnie beamed up at her and said, “Well, hey there! I am Linnie Mae, and this here is Junior. We’ve just moved into the neighborhood.”

“Is that so,” the woman said. “Well, I am Bertha. Sam’s wife. I bet you’re staying at the Murphys’, aren’t you.”

“Now, how did you know that?”

“Cora Lee stopped by and told me. She was just real tickled she’d found such a nice young couple. I said, ‘Honey, they’re the ones should be tickled.’ There’s no finer people around than Cora Lee and Joe Murphy.”

“I could tell that,” Linnie said. “I could tell straight off. I took one look at that sweet smiling face of hers and I could tell. She’s just like the people back home.”

“We’re all like the people back home,” Bertha said. “We all are the people back home. That’s what Hampden’s made up of.”

“Well, aren’t we lucky, then!”

Junior studied the price list on the wall behind the counter until they were finished talking.

Over the meatloaf, which turned out to taste better than anything he’d eaten in a good long while, Linnie told him she had a plan to lower their room rent. “You will keep your eyes open for some little thing that needs fixing,” she said. “Some loose board or saggy hinge or something. You’ll ask Cora Lee if it would be all right if you saw to it. Don’t mention money or nothing.”

“Anything,” he said.

She clamped her mouth shut.

“You’ve got to stop talking so country if you want to fit in here,” he told her.

“Well, and then a few days later you will fix something else. This time don’t ask; just fix it. She’ll hear the hammering and come running. ‘I hope you don’t mind,’ you tell her. ‘I just noticed it and I couldn’t resist.’ Of course she’ll say she doesn’t mind a bit; you can see from that leak in our ceiling that her husband’s not going to do it. Then you’ll say, ‘You know,’ you’ll say, ‘I’ve been thinking. Seems to me you want someone around to keep this house repaired, and it’s occurred to me that we might could work something out.’ ”

“Linnie, I think they need the cash,” he told her.

“Cash?”

“They’d rather let the house fall apart and go on eating, is what I’m saying.”

“Well, how could that be? They still need a roof over their heads! They still need a roof that doesn’t leak.”

“Tell me: are people not having hard times in Yancey County?” Junior asked.

“Well, sure they’re having hard times! Half the stores are closed and everyone’s out of work.”

“Then why don’t you understand about the Murphys? They’re probably one payment away from losing their house to the bank.”

“Oh,” Linnie Mae said.

“Nothing’s the same anymore,” he said. “No one’s in any position to cut us a deal. And no one can give you a job. You’ll use up your seven dollars and that will be the end of it, and I can’t afford to support you even if I wanted to. Do you know what’s in my Prince Albert tin? Forty-three dollars. That’s my entire life savings. It used to be a hundred and twenty before things changed. I’ve gone without for years, even in better times – given up smoking, given up drinking, eaten worse than my daddy’s dogs used to eat, and if my stomach felt too hollow I’d walk to the grocery store and buy a pickle from out of the barrel for a penny; a sour dill pickle can really kill a man’s appetite. I was Mrs. Davies’s longest-lasting roomer, and it’s not because I liked fighting five other men for the bathroom; it’s because I had ambitions. I wanted to start my own business. I wanted to build fine houses for people who knew to appreciate them – real slates on the roofs, real tiles on the floors, no more tarpaper and linoleum. I’d have good men under me, say Dodd McDowell and Gary Sherman from Ward Builders, and I’d drive my own truck with my company’s name on the sides. But for that, I’d need customers, and there aren’t any nowadays. Now I see it’s never going to happen.”

“Well, of course it will happen!” Linnie said. “Junior Whitshank! You think I don’t know, but I do: you went all the way through Mountain City High and never made less than an A. And you’ve been carpentering with your daddy since you were just a little thing, and everyone at the lumberyard knew you could answer any question that anybody there asked you. Oh, you’re bound to make it happen!”

“No,” he said, “that’s not the way it works anymore.” And then he said, “You need to go home, Linnie.”

Her lips flew apart. She said, “Home?”

“Have you even finished high school? You haven’t, have you.”

She raised her chin, which was answer enough.

“And your people will be wondering where you are.”

“It’s all the same to me if they’re wondering,” she said. “Anyhow, they don’t care. You know that me and Mama have never gotten along.”

“Still,” he said.

“And Daddy has not spoken to me in the last four years and ten months.”

Junior set his fork down. “What: not a word?” he asked.

“Not a single word. If he needs me to pass the salt, he tells Mama, ‘Get her to pass me the salt.’ ”

“Well, that is just spiteful,” Junior said.

“Oh, Junior, what did you imagine? I’d get caught with a boy in the hay barn and next day they’d all forget? For a while I thought you might come for me. I used to picture how it would happen. You’d pull up in your brother-in-law’s truck as I was walking down Pee Creek Road and ‘Get in,’ you’d tell me. ‘I’m taking you away from here.’ Then I thought maybe you’d send me a letter, with my ticket money inside. I’d have packed up and left in a minute, if you’d done that! It wasn’t only my daddy who didn’t speak to me; not much of anyone did. Even my two brothers acted different around me, and the girls who were nicey-nice at school were just trying to get close, it turned out, so that I’d tell them all the details. I thought when I went on to high school they wouldn’t know about it and I could make a fresh start, but of course they knew, because the kids from grade school who came along with me told them. ‘There’s Linnie Mae Inman,’ they’d say; ‘her and her boyfriend paraded stark nekkid through her brother’s graduation party.’ Because that’s what it had grown into, by then.”

“You act like it was my fault,” he told her. “You’re the one who started it.”

“I won’t say I didn’t. I was bad. But I was in love. I’m still in love! And I know that you are, too.”

He said, “Linnie—”

“Please, Junior,” she said. She was smiling, he didn’t know why, but there were tears in her eyes. “Give me a chance. Can’t you please do that? Don’t let’s talk about it just now; let’s enjoy our supper. Isn’t our supper good? Isn’t the meatloaf delicious?”

He looked down at his plate. “Yes,” he said, “it is.”

But he didn’t pick his fork up again.

On the walk home, she began asking him about his day-to-day life: how he spent his evenings, what he did on weekends, whether he had any friends. Even though he’d drunk nothing but water with his meal, he started to get that elated feeling that alcohol used to give him. It must have come from spilling all the words that he had kept stored up for so long. Because the fact was that he didn’t have any friends, not since Ward Builders shut down and he’d lost touch with the other workmen. (To be social, a person needed money – or men did, at any rate. They needed to buy liquor and hamburgers and gas; they couldn’t just sit around idle, chitchatting the way women did.) He told Linnie he did nothing with his evenings, he’d often as not spend them washing his clothes in the bathtub; and when she laughed, he said, “No, I mean it. And weekends I sleep a lot.” He was past shame; he told her straight out, not trying to look popular or successful or worldly-wise. They climbed the steps of the Murphys’ house and let themselves in the front door, passing the closed-off parlor where they could hear a radio playing – some kind of dance-band music – and the sound of two children good-naturedly squabbling about something. “You peeked; I saw!” “No I didn’t!” Even though it wasn’t Junior’s parlor and he had never met those children, he got a homey feeling.

They climbed the stairs and went to their room (no lock on this door), and right away Junior started worrying about what next. On his own, he would have gone to bed, since he always got such an early start in the mornings, but that might give Linnie the wrong idea. She might have the wrong idea even now; he sensed it from the demure way she took her coat off, and the care she took hanging it up. She removed her hat and placed it on the closet shelf. Her hair was in disarray and she patted it tentatively with just the tips of her fingers, keeping her back to him, as if she were getting ready for him. Something about the pale, meek nape of her neck, exposed by the accidental parting of her hair at the rear of her head, made him feel sorry for her. He cleared his throat and said, “Linnie Mae.”

She turned and said, “What?” And then she said, “Take your jacket off, why don’t you? Make yourself comfortable.”

“See, I’m trying to be honest,” he said. “I’d like to get everything clear between us.”

The beginnings of a crease developed between her eyebrows.

“I feel bad about what you’ve been through back home,” he said. “I guess it wasn’t much fun. But when you think about it, Linnie, what have we really got to do with each other? We hardly know each other! We went out together less than a month! And I’m trying to make it on my own up here. It’s hard enough for one; it’s impossible for two. Back home, at least you’ve got family. They’d never let you starve, no matter how they feel about you. I think you ought to go home.”

“You’re just saying that because you’re mad at me,” she told him.

“What? No, I’m not—”

“You’re mad I didn’t tell you how old I was, but why didn’t you ask how old I was? Why didn’t you ask if I was in school, or whether I worked someplace, or how I spent all the time that I wasn’t with you? Why weren’t you interested in me?”

“What? I was interested, honest!”

“Oh, we both know what you were interested in!”

“Hold on,” he said. “Is that fair? Who was the first to start taking her clothes off, might I remind you? And who dragged me into that barn? Who made me put my hand on her? Were you interested in how I spent my time?”

“Yes, I was,” she said. “And I asked you. Only you never bothered answering, because you were too busy trying to get me on my back. I said, ‘Tell me about your life, Junior; come on, I want to know everything about you.’ But did you tell me? No. You’d just start unbuttoning my buttons.”

Junior felt he was losing an argument that he didn’t even care about. He had wanted to make an entirely different point. He said, “Shoot, Linnie Mae,” and jammed his fists hard in his jacket pockets, except something in his left pocket stopped him and he pulled it out and looked at it. Half a sandwich, wrapped in a handkerchief.

“What’s that?” she asked him.

“It’s a … sandwich.”

“What kind of sandwich?”

“Egg? Egg.”

“Where’d you get an egg sandwich?”

“Lady I worked for today,” he said. “Half I ate and half I brought home to give to you, but then you were all set on us going out for supper.”

“Oh, Junior,” she said. “That’s so sweet!”

“No, I was just—”

“That was so nice of you!” she said, and she took the sandwich out of his hand, handkerchief and all. Her face was pink; she suddenly looked pretty. “I love it that you brought me a sandwich,” she said. She unwrapped it, reverently, and studied it a moment and then looked up at him with her eyes brimming.

“It’s squashed, though,” he said.

“I don’t care if it’s squashed! I love it that you thought about me while you were away at work. Oh, Junior, I’ve been so lonely all these years! You don’t know how lonely I’ve been. I’ve been so all, all alone all this time!”

And she flung herself on him, still holding that sandwich, and started sobbing.

After a moment, Junior lifted his arms and hugged her back.

She didn’t find a job, of course. That part of her plan didn’t work out. But her kitchen-sharing plan did. She and Cora Lee got to be friends, and they cooked together in the kitchen while they talked about whatever women talk about, and before long it just made more sense for Junior and Linnie to eat their meals with Cora Lee and her family. Then when the weather turned warm the two women hatched a plot to buy fruits and vegetables from the farmers who rolled into Hampden on their wagons, and they’d spend all day canning, blasting the kitchen with heat; and later Linnie would be the brave one who went around hawking their products to the neighbors. They didn’t make much money, but they made some.

And Junior actually did fix up a few things around the house, just because otherwise they would never have gotten done, but he didn’t charge anything or try to get a deal on the rent.

Even after times improved and Junior and Linnie moved into the house on Cotton Street, Linnie and Cora Lee stayed friends. Well, Linnie was friends with everybody, it seemed to Junior. Sometimes he wondered if those years of being an outcast had left her with an unnatural need to socialize. He’d come in after work and find wall-to-wall women in the kitchen, and all their mingled young ones playing in the backyard. “Don’t I get supper?” he would ask, and the women would scatter, rounding up their children on the way out. But he wouldn’t say Linnie was lazy. Oh, no. She and Cora still had their little canning business, and she answered the phone for Junior and saw to the billing and such as he began to have more customers. She was better with the customers than he was, in fact, always willing to take time for a little small talk, and adept at smoothing over any problems or complaints.

By then he had his truck – used, but it was a good one – and he had a few men working for him, and he owned a fine collection of tools that he’d bought from other men here and there who were down on their luck. These were really solid tools, the old-fashioned, beautifully made kind. A saw, for instance, with an oiled wooden handle that was carved with the most delicate and precise etching of a rosemary branch. It was true that the sweat that darkened the handle had not been his forebears’ sweat, but still he felt some personal pride in it. He always took excellent care of his tools. And he always went to lumberyards where he could choose his own lumber board by board. “Now, fellows, I know anything you might take it into your heads to put over on me. Don’t give me anything with dead knots, don’t give me anything warped or moldy …”

“What if I had been married?” he thought to ask Linnie years later. “What if you’d come up north and found me with a wife and six children?”

“Oh, Junior,” she said. “You would never do that.”

“What makes you so sure?”

“Well, for one thing, how would you get six children inside of just five years?”

“No, but, you know what I mean.”

She just smiled.

She acted older than he was, in some ways, and yet in other ways she seemed permanently thirteen – feisty and defiant, and stubbornly opinionated. He was taken aback to see how easily she had severed all connection with her family. It implied a level of bitterness that he had not suspected her capable of. She showed no desire to shed her backwoods style of speech; she still said “holler” for “shout,” and “tuckered” for “tired,” and “treckly” for “directly.” She still insisted on calling him “Junie.” She had an irritating habit of ostentatiously chuckling to herself before she told him something funny, as if she were coaching him to chuckle. She pressed too close to him when she wanted to persuade him of something. She plucked at his sleeve with picky fingers while he was talking to other people.

Oh, the terrible, crushing, breath-stealing burden of people who think they own you!

And if Junior was the wild one, how come it was Linnie Mae who’d caused every single bit of trouble he’d found himself in since they’d met?

He was a sharp-boned, narrow-ribbed man, a man without an ounce of fat who had never had much interest in food, but sometimes when he came home from work in the late afternoon and Linnie was out back gabbing with her next-door neighbor he would stand in front of the refrigerator and eat all the leftover pork chops and then the wieners, the cold mashed potatoes, the cold peas and the boiled beets, foods he didn’t even like, as if he were starving, as if he had never gotten what he really wanted, and later Linnie would say, “Have you seen those peas I was saving? Where are those peas?” and he would stay stone silent. She had to know. What did she think: little Merrick craved cold peas? But she never said so. This made him feel both grateful and resentful. Lord it over him, would she! She must really think she had his number!

At such moments he would run his mind back through that long-ago trip to the train station, this time doing it differently. Down the dark streets, turn right past the station, turn right again onto Charles Street and drive back to the boardinghouse. Let himself into his room and lock the door behind him. Drop onto his cot. Fall asleep alone.