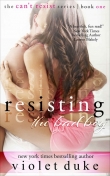

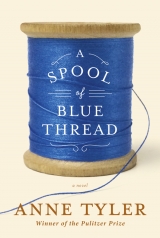

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Anne Tyler

A Spool of Blue Thread

PART ONE. Can’t Leave Till the Dog Dies

1

LATE ONE JULY EVENING IN 1994, Red and Abby Whitshank had a phone call from their son Denny. They were getting ready for bed at the time. Abby was standing at the bureau in her slip, drawing hairpins one by one from her scattery sand-colored topknot. Red, a dark, gaunt man in striped pajama bottoms and a white T-shirt, had just sat down on the edge of the bed to take his socks off; so when the phone rang on the nightstand beside him, he was the one who answered. “Whitshank residence,” he said.

And then, “Well, hey there.”

Abby turned from the mirror, both arms still raised to her head.

“What’s that,” he said, without a question mark.

“Huh?” he said. “Oh, what the hell, Denny!”

Abby dropped her arms.

“Hello?” he said. “Wait. Hello? Hello?”

He was silent for a moment, and then he replaced the receiver.

“What?” Abby asked him.

“Says he’s gay.”

“What?”

“Said he needed to tell me something: he’s gay.”

“And you hung up on him!”

“No, Abby. He hung up on me. All I said was ‘What the hell,’ and he hung up on me. Click! Just like that.”

“Oh, Red, how could you?” Abby wailed. She spun away to reach for her bathrobe – a no-color chenille that had once been pink. She wrapped it around her and tied the sash tightly. “What possessed you to say that?” she asked him.

“I didn’t mean anything by it! Somebody springs something on you, you’re going to say ‘What the hell,’ right?”

Abby grabbed a handful of the hair that pouffed over her forehead.

“All I meant was,” Red said, “ ‘What the hell next, Denny? What are you going to think up next to worry us with?’ And he knew I meant that. Believe me, he knew. But now he can make this all my fault, my narrow-mindedness or fuddy-duddiness or whatever he wants to call it. He was glad I said that to him. You could tell by how fast he hung up on me; he’d been just hoping all along that I would say the wrong thing.”

“All right,” Abby said, turning practical. “Where was he calling from?”

“How would I know where he was calling from? He doesn’t have a fixed address, hasn’t been in touch all summer, already changed jobs twice that we know of and probably more that we don’t know of … A nineteen-year-old boy and we have no idea what part of the planet he’s on! You’ve got to wonder what’s wrong, there.”

“Did it sound like it was long distance? Could you hear that kind of rushing sound? Think. Could he have been right here in Baltimore?”

“I don’t know, Abby.”

She sat down next to him. The mattress slanted in her direction; she was a wide, solid woman. “We have to find him,” she said. Then, “We should have that whatsit – caller ID.” She leaned forward and gazed fiercely at the phone. “Oh, God, I want caller ID this instant!”

“What for? So you could phone him back and he could just let it ring?”

“He wouldn’t do that. He would know it was me. He would answer, if he knew it was me.”

She jumped up from the bed and started pacing back and forth, up and down the Persian runner that was worn nearly white in the middle from all the times she had paced it before. This was an attractive room, spacious and well designed, but it had the comfortably shabby air of a place whose inhabitants had long ago stopped seeing it.

“What did his voice sound like?” she asked. “Was he nervous? Was he upset?”

“He was fine.”

“So you say. Had he been drinking, do you think?”

“I couldn’t tell.”

“Were other people with him?”

“I couldn’t tell, Abby.”

“Or maybe … one other person?”

He sent her a sharp look. “You are not thinking he was serious,” he said.

“Of course he was serious! Why else would he say it?”

“The boy isn’t gay, Abby.”

“How do you know that?”

“He just isn’t. Mark my words. You’re going to feel silly, by and by, like, ‘Shoot, I overreacted.’ ”

“Well, naturally that is what you would want to believe.”

“Doesn’t your female intuition tell you anything at all? This is a kid who got a girl in trouble before he was out of high school!”

“So? That doesn’t mean a thing. It might even have been a symptom.”

“Come again?”

“We can never know with absolute certainty what another person’s sex life is like.”

“No, thank God,” Red said.

He bent over, with a grunt, and reached beneath the bed for his slippers. Abby, meanwhile, had stopped pacing and was staring once more at the phone. She set a hand on the receiver. She hesitated. Then she snatched up the receiver and pressed it to her ear for half a second before slamming it back down.

“The thing about caller ID is,” Red said, more or less to himself, “it seems a little like cheating. A person should be willing to take his chances, answering the phone. That’s kind of the general idea with phones, is my opinion.”

He heaved himself to his feet and started toward the bathroom. Behind him, Abby said, “This would explain so much! Wouldn’t it? If he should turn out to be gay.”

Red was closing the bathroom door by then, but he poked his head back out to glare at her. His fine black eyebrows, normally straight as rulers, were knotted almost together. “Sometimes,” he said, “I rue and deplore the day I married a social worker.”

Then he shut the door very firmly.

When he returned, Abby was sitting upright in bed with her arms clamped across the lace bosom of her nightgown. “You are surely not going to try and blame Denny’s problems on my profession,” she told him.

“I’m just saying a person can be too understanding,” he said. “Too sympathizing and pitying, like. Getting into a kid’s private brain.”

“There is no such thing as ‘too understanding.’ ”

“Well, count on a social worker to think that.”

She gave an exasperated puff of a breath, and then she sent another glance toward the phone. It was on Red’s side of the bed, not hers. Red raised the covers and got in, blocking her view. He reached over and snapped off the lamp on the nightstand. The room fell into darkness, with just a faint glow from the two tall, gauzy windows overlooking the front lawn.

Red was lying flat now, but Abby went on sitting up. She said, “Do you think he’ll call us back?”

“Oh, yes. Sooner or later.”

“It took all his courage to call the first time,” she said. “Maybe he used up every bit he had.”

“Courage! What courage? We’re his parents! Why would he need courage to call his own parents?”

“It’s you he needs it for,” Abby said.

“That’s ridiculous. I’ve never raised a hand to him.”

“No, but you disapprove of him. You’re always finding fault with him. With the girls you’re such a softie, and then Stem is more your kind of person. While Denny! Things come harder to Denny. Sometimes I think you don’t like him.”

“Abby, for God’s sake. You know that’s not true.”

“Oh, you love him, all right. But I’ve seen the way you look at him—‘Who is this person?’—and don’t you think for a moment that he hasn’t seen it too.”

“If that’s the case,” Red said, “how come it’s you he’s always trying to get away from?”

“He’s not trying to get away from me!”

“From the time he was five or six years old, he wouldn’t let you into his room. Kid preferred to change his own sheets rather than let you in to do it for him! Hardly ever brought his friends home, wouldn’t say what their names were, wouldn’t even tell you what he did in school all day. ‘Get out of my life, Mom,’ he was saying. ‘Stop meddling, stop prying, stop breathing down my neck.’ His least favorite picture book – the one he hated so much he tore out all the pages, remember? – had that baby rabbit that wants to change into a fish and a cloud and such so he can get away, and the mama rabbit keeps saying how she will change too and come after him. Denny ripped out every single everlasting page!”

“That had nothing to do with—”

“You wonder why he’s turned gay? Not that he has turned gay, but if he had, if it’s crossed his mind just to bug us with that, you want to know why? I’ll tell you why: it’s the mother. It is always the smothering mother.”

“Oh!” Abby said. “That is just so outdated and benighted and so … wrong, I’m not even going to dignify it with an answer.”

“You’re certainly using a lot of words to tell me so.”

“And how about the father, if you want to go back to the Dark Ages for your theories? How about the macho, construction-guy father who tells his son to buck up, show some spunk, quit whining about the small stuff, climb the darn roof and hammer the slates in?”

“You don’t hammer slates in, Abby.”

“How about him?” she asked.

“Okay, fine! I did that. I was the world’s worst parent. It’s done.”

There was a moment of quiet. The only sound came from outside – the whisper of a car slipping past.

“I didn’t say you were the worst,” Abby said.

“Well,” Red said.

Another moment of quiet.

Abby asked, “Isn’t there a number you can punch that will dial the last person who called?”

“Star sixty-nine,” Red said instantly. He cleared his throat. “But you are surely not going to do that.”

“Why not?”

“Denny was the one who chose to end the conversation, might I point out.”

“His feelings were hurt, was why,” Abby said.

“If his feelings were hurt, he’d have taken his time hanging up. He wouldn’t have been so quick to cut me off. But he hung up like he was just waiting to hang up. Oh, he was practically rubbing his hands together, giving me that news! He starts right in. ‘I’d like to tell you something,’ he says.”

“Before, you said it was ‘I need to tell you something.’ ”

“Well, one or the other,” Red said.

“Which was it?”

“Does it matter?”

“Yes, it matters.”

He thought a moment. Then he tried it out under his breath. “ ‘I need to tell you something,’ ” he tried. “ ‘I’d like to tell you something.’ ‘Dad, I’d like to—’ ” He broke off. “I honestly don’t remember,” he said.

“Could you dial star sixty-nine, please?”

“I can’t figure out his reasoning. He knows I’m not anti-gay. I’ve got a gay guy in charge of our drywall, for Lord’s sake. Denny knows that. I can’t figure out why he thought this would bug me. I mean, of course I’m not going to be thrilled. You always want your kid to have it as easy in life as he can. But—”

“Hand me the phone,” Abby said.

The phone rang.

Red grabbed the receiver at the very same instant that Abby flung herself across him to grab it herself. He had it first, but there was a little tussle and somehow she was the one who ended up with it. She sat up straight and said, “Denny?”

Then she said, “Oh. Jeannie.”

Red lay flat again.

“No, no, we’re not in bed yet,” she said. There was a pause. “Certainly. What’s wrong with yours?” Another pause. “It’s no trouble at all. I’ll see you at eight tomorrow. Bye.”

She held the receiver toward Red, and he took it from her and reached over to replace it in its cradle.

“She wants to borrow my car,” she told him. She sank back onto her side of the bed.

Then she said, in a thin, lonesome-sounding voice, “I guess star sixty-nine won’t work now, will it.”

“No,” Red said, “I guess not.”

“Oh, Red. Oh, what are we going to do? We’ll never, ever hear from him again! He’s not going to give us another chance!”

“Now, hon,” he told her. “We’ll hear from him. I promise.” And he reached for her and drew her close, settling her head on his shoulder.

They lay like that for some time, until gradually Abby stopped fidgeting and her breaths grew slow and even. Red, though, went on staring up into the dark. At one point, he mouthed some words to himself in an experimental way. “ ‘… need to tell you something,’ ” he mouthed, not even quite whispering it. Then, “ ‘… like to tell you something.’ ” Then, “ ‘Dad, I’d like to …’ ‘Dad, I need to …’ ” He tossed his head impatiently on his pillow. He started over. “ ‘… tell you something: I’m gay.’ ‘… tell you something: I think I’m gay.’ ‘I’m gay.’ ‘I think I’m gay.’ ‘I think I may be gay.’ ‘I’m gay.’ ”

But eventually he grew silent, and at last he fell asleep too.

Well, of course they did hear from him again. The Whitshanks weren’t a melodramatic family. Not even Denny was the type to disappear off the face of the earth, or sever all contact, or stop speaking – or not permanently, at least. It was true that he skipped the beach trip that summer, but he might have skipped it anyhow; he had to make his pocket money for the following school year. (He was attending St. Eskil College, in Pronghorn, Minnesota.) And he did telephone in September. He needed money for textbooks, he said. Unfortunately, Red was the only one home at the time, so it wasn’t a very revealing conversation. “What did you talk about?” Abby demanded, and Red said, “I told him his textbooks had to come out of his earnings.”

“I mean, did you talk about that last phone call? Did you apologize? Did you explain? Did you ask him any questions?”

“We didn’t really get into it.”

“Red!” Abby said. “This is classic! This is such a classic reaction: a young person announces he’s gay and his family just carries on like before, pretending they didn’t hear.”

“Well, fine,” Red said. “Call him back. Get in touch with his dorm.”

Abby looked uncertain. “What reason should I give him for calling?” she asked.

“Say you want to grill him.”

“I’ll just wait till he phones again,” she decided.

But when he phoned again – which he did a month or so later, when Abby was there to answer – it was to talk about his plane reservations for Christmas vacation. He wanted to change his arrival date, because first he was going to Hibbing to visit his girlfriend. His girlfriend! “What could I say?” Abby asked Red later. “I had to say, ‘Okay, fine.’ ”

“What could you say,” Red agreed.

He didn’t refer to the subject again, but Abby herself sort of simmered and percolated all those weeks before Christmas. You could tell she was just itching to get things out in the open. The rest of the family edged around her warily. They knew nothing about the gay announcement – Red and Abby had concurred on that much, not to tell them without Denny’s say-so – but they could sense that something was up.

It was Abby’s plan (though not Red’s) to sit Denny down and have a nice heart-to-heart as soon as he got home. But on the morning of the day that his plane was due in, they had a letter from St. Eskil reminding them of the terms of their contract: the Whitshanks would be responsible for the next semester’s tuition even though Denny had withdrawn.

“ ‘Withdrawn,’ ” Abby repeated. She was the one who had opened the letter, although both of them were reading it. The slow, considering way she spoke brought out all the word’s ramifications. Denny had withdrawn; he was withdrawn; he had withdrawn from the family years ago. What other middle-class American teenager lived the way he did – flitting around the country like a vagrant, completely out of his parents’ control, getting in touch just sporadically and neglecting whenever possible to give them any means of getting in touch with him? How had things come to such a pass? They certainly hadn’t allowed the other children to behave this way. Red and Abby looked at each other for a long, despairing moment.

Understandably, therefore, the subject that dominated Christmas that year was Denny’s leaving school. (He had decided school was a waste of money, was all he had to say, since he didn’t have the least idea what he wanted to do in life. Maybe in a year or two, he said.) His gayness, or his non-gayness, just seemed to get lost in the shuffle.

“I can almost see now why some families pretend they weren’t told,” Abby said after the holidays.

“Mm-hmm,” Red said, poker-faced.

Of Red and Abby’s four children, Denny had always been the best-looking. (A pity more of those looks hadn’t gone to the girls.) He had the Whitshank straight black hair and narrow, piercing blue eyes and chiseled features, but his skin was one shade tanner than the paper-white skin of the others, and he seemed better put together, not such a bag of knobs and bones. Yet there was something about his face – some unevenness, some irregularity or asymmetry – that kept him from being truly handsome. People who remarked on his looks did so belatedly, in a tone of surprise, as if they were congratulating themselves on their powers of discernment.

In birth order, he came third. Amanda was nine when he was born, and Jeannie was five. Was it hard on a boy to have older sisters? Intimidating? Demeaning? Those two could be awfully sure of themselves – especially Amanda, who had a bossy streak. But he shrugged Amanda off, more or less, and with tomboyish little Jeannie he was mildly affectionate. So, no warning bells there. Stem, though! Stem had come along when Denny was four. Now, that could have been a factor. Stem was just naturally good. You see such children, sometimes. He was obedient and sweet-tempered and kind; he didn’t even have to try.

Which was not to say that Denny was bad. He was far more generous, for instance, than the other three put together. (He traded his new bike for a kitten when Jeannie’s beloved cat died.) And he didn’t bully other children, or throw tantrums. But he was so close-mouthed. He had these spells of unexplained obstinacy, where his face would grow set and pinched and no one could get through to him. It seemed to be a kind of inward tantrum; it seemed his anger turned in upon itself and hardened him or froze him. Red threw up his hands when that happened and stomped off, but Abby couldn’t let him be. She just had to jostle him out of it. She wanted her loved ones happy!

One time in the grocery store, when Denny was in a funk for some reason, “Good Vibrations” started playing over the loudspeaker. It was Abby’s theme song, the one she always said she wanted for her funeral procession, and she began dancing to it. She dipped and sashayed and dum-da-da-dummed around Denny as if he were a maypole, but he just stalked on down the soup aisle with his eyes fixed straight ahead and his fists jammed into his jacket pockets. Made her look like a fool, she told Red when she got home. (She was trying to laugh it off.) He never even glanced at her! She might have been some crazy lady! And this was when he was nine or ten, nowhere near that age yet when boys find their mothers embarrassing. But he had found Abby embarrassing from earliest childhood, evidently. He acted as if he’d been assigned the wrong mother, she said, and she just didn’t measure up.

Now she was being silly, Red told her.

And Abby said yes, yes, she knew that. She hadn’t meant it the way it sounded.

Teachers phoned Abby repeatedly: “Could you come in for a talk about Denny? As soon as possible, please.” The issue was inattention, or laziness, or carelessness; never a lack of ability. In fact, at the end of third grade he was put ahead a year, on the theory that he might just need a bigger challenge. But that was probably a mistake. It made him even more of an outsider. The few friends he had were questionable friends – boys who didn’t go to his school, boys who made the rest of the family uneasy on the rare occasions they showed themselves, mumbling and shifting their feet and looking elsewhere.

Oh, there were moments of promise, now and then. He won a prize in a science contest, once, for designing a form of packaging that would keep an egg from cracking no matter how far you threw it. But that was the last contest he entered. And one summer he took up the French horn, which he’d had a few lessons in during elementary school, and he showed more perseverance than the family had ever seen in him. For several weeks a bleating, blurting, fogged version of Mozart’s Horn Concerto No. 1 stumbled through the closed door of his room hour after hour, haltingly, relentlessly, till Red began cursing under his breath; but Abby patted Red’s hand and said, “Oh, now, it could be worse. It could be the Butthole Surfers,” which was Jeannie’s music of choice at the time. “I just think it’s wonderful that he’s found himself a project,” she said, and whenever Denny paused a few measures for the orchestral parts, she would tra-la-la the missing notes. (The entire family knew the piece by heart now, since it blared from the stereo any time that Denny wasn’t playing it himself.) But once he could make it through the first movement without having to go back and start over, he gave it up. He said French horn was boring. “Boring” seemed to be his favorite word. Soccer camp was boring, too, and he dropped out after three days. Same for tennis; same for swim team. “Maybe we should cool it,” Red suggested to Abby. “Not act all excited whenever he shows an interest in something.”

But Abby said, “We’re his parents! Parents are supposed to be excited.”

Although he guarded his privacy obsessively – behaved as if he had state secrets to hide – Denny himself was an inveterate snoop. Nothing was safe from him. He read his sisters’ diaries and his mother’s client files. He left desk drawers suspiciously smooth on top but tumbled about underneath.

And then when he reached his teens there was the drinking, the smoking, the truancy, the pot and maybe worse. Battered cars pulled up to the house with unfamiliar drivers honking and shouting, “Yo, Shitwank!” Twice he got in trouble with the police. (Driving without a license; fake ID.) His style of dress went way beyond your usual adolescent grunge: old men’s overcoats bought at flea markets; crusty, baggy tweed pants; sneakers held together with duct tape. His hair was unwashed, ropy with grease, and he gave off the smell of a musty clothes closet. He could have been a homeless person. Which was so ironic, Abby told Red. A blood member of the Whitshank family, one of those enviable families that radiate clannishness and togetherness and just … specialness; but he trailed around their edges like some sort of charity case.

By then both boys were working part-time at Whitshank Construction. Denny proved competent, but not so good with the customers. (To a woman who said, flirtatiously, “I worry you’ll stop liking me if I tell you I’ve changed my mind about the paint color,” his answer was “Who says I ever liked you in the first place?”) Stem, on the other hand, was obliging with the customers and devoted to the work – staying late, asking questions, begging for another project. Something involving wood, he begged. Stem loved to deal with wood.

Denny developed a lofty tone of voice, supercilious and amused. “Certainly, my man,” he would answer when Stem asked for the sports section, and “Whatever you say, Abigail.” At Abby’s well-known “orphan dinners,” with their assemblages of misfits and loners and unfortunates, Denny’s courtly behavior came across first as charming and then as offensive. “Please, I insist,” he told Mrs. Mallon, “have my chair; it can bear your weight better.” Mrs. Mallon, a stylish divorcee who took pride in her extreme thinness, cried, “Oh! Why—” but he said, “Your chair’s kind of fragile,” and his parents couldn’t do a thing, not without drawing even more attention to the situation. Or B. J. Autry, a raddled blonde whose harsh, cawing laugh made everyone wince: Denny devoted a whole Easter Sunday to complimenting her “bell-like tinkle.” Though B. J., for one, gave as good as she got. “Buzz off, kid,” she said finally. Red hauled Denny over the coals afterward. “In this house,” he said, “we don’t insult our guests. You owe B. J. an apology.”

Denny said, “Oh, my mistake. I didn’t realize she was such a delicate flower.”

“Everybody’s delicate, son, if you poke them hard enough.”

“Really? Not me,” Denny said.

Of course they thought of sending him to therapy. Or Abby did, at least. All along she had thought of it, but now she grew more insistent. Denny refused. One day during his junior year, she asked his help taking the dog to the vet – a two-person job. After they’d dragged Clarence into the car, Denny threw himself on the front seat and folded his arms across his chest, and they set off. Behind them, Clarence whimpered and paced, scritching his toenails across the vinyl upholstery. The whimpers turned to moans as the vet’s office drew closer. Abby sailed past the vet and kept going. The moans became fainter and more questioning, and eventually they stopped. Abby drove to a low stucco building, parked in front and cut the engine. She walked briskly around to the passenger side and opened the door for Denny. “Out,” she ordered. Denny sat still for a moment but then obeyed, unfolding himself so slowly and so grudgingly that he almost oozed out. They climbed the two steps to the building’s front stoop, and Abby punched a button next to a plaque reading RICHARD HANCOCK, M.D. “I’ll collect you in fifty minutes,” she said. Denny gave her an impassive stare. When a buzzer sounded, he opened the door, and Abby returned to the car.

Red had trouble believing this story. “He just walked in?” he asked Abby. “He just went along with it?”

“Of course,” Abby said breezily, and then her eyes filled with tears. “Oh, Red,” she said, “can you imagine what a hard time he must be having, if he let me do that?”

Denny saw Dr. Hancock weekly for two or three months. “Hankie,” he called him. (“I’ve got no time to clean the basement; it’s a goddamn Hankie day.”) He never said what they talked about, and Dr. Hancock of course didn’t, either, although Abby phoned him once to ask if he thought a family conference might be helpful. Dr. Hancock said he did not.

This was in 1990, late 1990. In early 1991, Denny eloped.

The girl was named Amy Lin. She was the wishbone-thin, curtain-haired, Goth-costumed daughter of two Chinese-American orthopedists, and she was six weeks pregnant. But none of this was known to the Whitshanks. They had never heard of Amy Lin. Their first inkling came when her father phoned and asked if they had any idea of Amy’s whereabouts. “Who?” Abby said. She thought at first he must have dialed the wrong number.

“Amy Lin, my daughter. She’s gone off with your son. Her note said they’re getting married.”

“They’re what?” Abby said. “He’s sixteen years old!”

“So is Amy,” Dr. Lin said. “Her birthday was day before yesterday. She seems to be under the impression that sixteen is legal marrying age.”

“Well, maybe in Mozambique,” Abby said.

“Could you check Denny’s room for a note, please? I’ll wait.”

“All right,” Abby said. “But I really think you’re mistaken.”

She laid the receiver down and called for Jeannie – the one most familiar with Denny’s ways – to help her look for a note. Jeannie was just as disbelieving as Abby. “Denny? Married?” she asked as they climbed the stairs. “He doesn’t even have a girlfriend!”

“Oh, clearly the man is bonkers,” Abby said. “And so imperious! He introduced himself as ‘Dr. Lin.’ He had that typical doctor way of ordering people about.”

Naturally, they didn’t find a note, or anything else telltale – a love letter or a photograph. Jeannie even checked a tin box on Denny’s closet shelf that Abby hadn’t known about, but all it held was a pack of Marlboros and a matchbook. “See?” Abby said triumphantly.

But Jeannie wore a thoughtful expression, and on their way back down the stairs she said, “When has Denny ever left a note, though, for any reason?”

“Dr. Lin has it all wrong,” Abby said with finality. She picked up the receiver and said, “It appears that you’re wrong, Dr. Lin.”

So it was left to the Lins to locate the couple, after their daughter called them collect to tell them she was fine although maybe the teeniest bit homesick. She and Denny were holed up in a motel outside Elkton, Maryland, having run into a snag when they tried to apply for a marriage license. By that time they had been missing three days, so the Whitshanks were forced to admit that Dr. Lin must not be bonkers after all, although they still couldn’t quite believe that Denny would do such a thing.

The Lins drove to Elkton to retrieve them, returning directly to the Whitshank house to hold a two-family discussion. It was the first and only time that Red and Abby laid eyes on Amy. They found her bewilderingly unattractive – sallow and unhealthy-looking, and lacking any sign of spirit. Also, as Abby said later, it was a jolt to see how well the Lins seemed to know Denny. Amy’s father, a small man in a powder-blue jogging suit, spoke to him familiarly and even kindly, and her mother patted Denny’s hand in a consoling way after he finally allowed that an abortion might be wiser. “Denny must have been to their house any number of times,” Abby told Red, “while you and I didn’t realize Amy even existed.”

“Well, it’s different with daughters,” Red said. “You know how we generally get to meet Mandy and Jeannie’s young men, but I’m not sure the young men’s parents always meet Mandy and Jeannie.”

“No,” Abby said, “that’s not what I’m talking about. This is more like he didn’t just meet her family; he joined it.”

“Rubbish,” Red told her.

Abby didn’t seem reassured.

They did try to talk with Denny about the elopement once the Lins left, but all he would say was that he’d been looking forward to taking care of a baby. When they said he was too young to take care of a baby, he was silent. And when Stem asked, in his clumsy, puppyish way, “So are you and Amy, like, engaged now?” Denny said, “Huh? I don’t know.”

In fact, the Whitshanks never saw Amy again, and as far as they could tell, Denny didn’t, either. By the end of the next week he was safely installed in a boarding school for problem teenagers up in Pennsylvania, thanks to Dr. Hancock, who made all the arrangements. Denny completed his junior and senior years there, and since he claimed to have no interest in construction work, he spent both summers busing tables in Ocean City. The only times he came home anymore were for major events, like Grandma Dalton’s funeral or Jeannie’s wedding, and then he was gone again in a flash.

It wasn’t right, Abby said. They hadn’t had him long enough. Children were supposed to stick around till eighteen, at the very least. (The girls hadn’t moved away even for college.) “It’s like he’s been stolen from us,” she told Red. “He was taken before his time!”

“You talk like he’s died,” Red told her.

“I feel like he’s died,” she said.

And whenever he did come home, he was a stranger. He had a different smell, no longer the musty-closet smell but something almost chemical, like new carpeting. He wore a Greek sailor’s cap that Abby (a product of the sixties) associated with the young Bob Dylan. And he spoke to his parents politely, but distantly. Did he resent them for shipping him off? But they hadn’t had a choice! No, his grudge must have gone farther back. “It’s because I didn’t shield him properly,” Abby guessed.