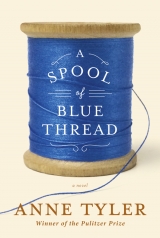

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

13

JUNIOR HAD EUGENE take the porch swing down to Tilghman Brothers, an establishment near the waterfront where Whitshank Construction sent customers’ shutters when they were so thick with paint that they resembled half-sucked toffees. Evidently the Tilghman brothers owned a giant vat of some caustic solution that stripped everything to the bare wood. “Tell them we need the swing back in exactly a week,” Junior told Eugene.

“A week from today?”

“That’s what I said.”

“Boss, those fellows can take a month with such things. They don’t like to be hurried.”

“Tell them it’s an emergency. Say we’ll pay extra, if we have to. Moving day is two Sundays from now, and I want the swing hanging by then.”

“Well, I’ll try, boss,” Eugene said.

Junior could see that Eugene was thinking this was an awful lot of fuss for a mere porch swing, but he had the good sense not to say so. Eugene was an experiment – Junior’s first colored employee, hired when the draft had claimed one of the company’s painters. He was working out okay, so far. In fact, last week Junior had hired another.

Linnie Mae had been worrying lately that Junior would be drafted himself. When he pointed out that he was forty-two years old, she said, “I don’t care; they could raise the draft age any day now. Or you might decide to enlist.”

“Enlist!” he said. “What kind of fool do you take me for?”

He had the feeling sometimes that his life was like a railroad car that had been shunted onto a side track for years – all the wasted, wild years of his youth and the years of the Depression. He was lagging behind; he was running to catch up; he was finally on the main track and he would be damned if some war in Europe was going to stop him.

When the swing came back it was virgin wood – a miracle. Not the tiniest speck of blue in the least little seam. Junior walked all around it, marveling. “Lord, I hate to think what-all they must have in that vat,” he told Eugene.

Eugene chuckled. “You want I should varnish it?” he asked.

“No,” Junior said, “I’ll do that.”

Eugene shot him a look of surprise, but he didn’t comment.

The two of them carried it out back and set it upside down on a drop cloth, so that Junior could varnish the underside first and give it time to dry before he turned it over. It was a warm May day with no rain in the forecast, so Junior figured he could safely leave it out overnight and come back the next morning to do the rest.

Like most carpenters, he had an active dislike of painting, and also he was conscious that he wasn’t very good at it. But for some reason it seemed important to accomplish this task on his own, and he worked carefully and patiently, even though this was the part of the swing that wouldn’t show. It was a pleasant occupation, really. The sunlight was filtering through the trees, and a breeze was cooling his face, and “Chattanooga Choo Choo” was playing in his mind.

You leave the Pennsylvania Station ’bout a quarter to four,

Read a magazine and then you’re in Baltimore …

When he was done, he cleaned his brush and put away the varnish and the mineral spirits, and he went home for supper feeling pleased with himself.

The next morning he came back to finish the job. The swing was dry, but a fine dusting of pollen was stuck to the underside of the seat. He should have foreseen that. No wonder he hated painting! Cursing beneath his breath, he dragged the drop cloth toward the back porch with the swing along for the ride. Then he spread another drop cloth inside the enclosed end of the porch and hauled the swing in and set it right side up. This was going to be done properly, by God. He tried to forget how the lower surfaces of the armrests had rasped against his fingertips when he grabbed hold of them.

Eugene had painted the back porch interior earlier in the week, and the smells of paint and varnish combined to make Junior feel slightly light-headed. He drew the brush along the wood with dreamy strokes. Wasn’t it interesting how the grain of the wood told a story, almost – how you could follow the threads and be surprised at how far they traveled, or where they unexpectedly broke off.

He wondered if someday Merrick would be proposed to in this swing, if Redcliffe’s children would swoop back and forth in it so raucously that their mother would seize the ropes to slow it down.

After Junior learned how a man could feel about his children, he had conceived a deep and permanent anger toward his father. His father had had six sons and a daughter, and he’d let them loose easier than a dog lets loose of her pups. The older Junior got, the harder he found it to understand that.

He made a quick, sharp, shaking-away motion with his head, and he dipped his brush again.

This varnish was the color of buckwheat honey. It drew out the character of the wood and added depth. No more of those eternal Swedish-blue swings of home! No more raggedy braided rugs and rusted metal gliders; no more baby-blue porch ceilings that were meant, he supposed, to suggest the sky; no more battleship-gray porch floors.

Linnie was going to start up the walk on moving day, and at the foot of the porch steps, “Oh!” she would say. She would be staring at the swing; one hand would fly to her mouth. “Oh, why—!” Or maybe not. Maybe she would conceal her surprise; she might be crafty enough. Either way, Junior himself would climb the steps without breaking stride. He wouldn’t give a sign that anything was different. “Shall we go in?” he would ask her, and he would turn to her and gesture hospitably toward the front door.

There was a satisfaction to imagining this scene, and yet he felt something was lacking. She wouldn’t fully realize all that lay behind it: his shock at what she had done and his outrage and his sense of injustice, and his hard work to repair the damage. Eugene’s trip to Tilghman Brothers, the exorbitant fee they had charged for the expedited service (exactly double their regular fee), Junior’s two separate trips to apply the varnish and the final trip he would make Friday morning to screw the eyebolts back in and reattach the ropes on their figure eights and hang the swing from the ceiling: she would have no idea of any of that. It echoed the pattern of their lives together – all the secrets he had kept from her despite his temptation to tell. She would never know how deeply he had longed to free himself all these years, how he had stayed with her only because he knew she would be lost otherwise, how onerous it had been to go on and on, day after day, setting right what he had done wrong. No, she had absolute faith that he had stayed because he loved her. And if he told her otherwise – if he somehow managed to convince her of his sacrifice – she would be crushed, and the sacrifice would have been for nothing.

He circled each spindle with his brush, smoothing varnish into each joint, tracing the crevices of the lathing with tender, caressing strokes.

Dinner in the diner,

nothing could be finer

Than to have your ham ’n’ eggs in Carolina …

On Friday when he went back to hang the swing he took along more boxes from home and a few small pieces of furniture – the play table from the children’s room and the little chairs that went with it. Might as well haul as much as possible over ahead of time. He parked in the rear and carried everything in through the kitchen and up the stairs. While he was up there, he indulged himself in a survey of his new property. He stood at the hall railing to admire the gleaming entrance hall below, and he stepped into the main bedroom to gloat over its spaciousness. His and Linnie’s beds were already in place – twin beds, like those the Brills had had, delivered last week by Shofer’s. Linnie couldn’t understand why they didn’t keep on sharing their old double, but Junior said, “It just makes more sense, when you think about it. You know how I’m always tossing and turning in the middle of the night.”

“I don’t mind you tossing and turning,” Linnie said.

“Well, we’ll just try this out, why don’t we. We’re not throwing the double away, after all. If we change our minds we can always move it back in from the guest room.”

Although privately, he had no intention of moving it back. He liked the idea of twin beds – their Hollywood-style glamour. Besides, he’d spent enough of his childhood sharing a bed with various brothers.

In the far corner of the bedroom stood the Brills’ armoire, which he also considered glamorous. It made his cheeks burn, though, to remember that he had first understood it to be called a “more.” “Mrs. Brill,” he had said, “I hear you’re not taking your more to the new place. You think I could buy it off you?”

Mrs. Brill’s eyebrows had knotted. “My—?” she said.

“Your more in the bedroom. Your boy said it was too big.”

“Oh! Why, certainly. Jim? Junior was just wondering if he could buy our armoire.”

It wasn’t till then that Junior had realized his mistake. He was furious at Mrs. Brill for witnessing it, even though he had to admit that she had behaved very tactfully.

In a way, it was her tact he was furious at.

Oh, always, always it was us-and-them. Whether it was the town kids in high school or the rich people in Roland Park, always someone to point out that he wasn’t quite measuring up, he didn’t quite make the grade. And it was assumed to be his own fault, because he lived in a nation where theoretically, he could make the grade. There was nothing to hold him back. Except that there was something; he couldn’t quite put his finger on it. There was always some little tiny trick of dress or of speech that kept him on the outside looking in.

Nonsense. Enough. He owned a giant cedar-lined closet now that was meant for storing nothing but woolens. The wallpaper in this bedroom came all the way from France. The windows were so tall that when he stood at one, a person down on the street could see from the top of Junior’s head almost to his knees.

But then he noticed a patch of blistered paint at the corner of one sill. The Brills must have left that window open during a rainstorm. Or else it was the result of condensation; that would not be good.

Also, the wallpaper underneath it was showing its seam too distinctly. In fact, the seam was separating. In fact, where the paper met the sill it was actually curling up from the wall a tiny bit.

Saturday was the day he went around giving estimates; that was when the husbands were home. So he didn’t stop by the new house. He wrapped up his appointments early, because tomorrow they were moving and there was still some packing to do. He got home about three o’clock and walked on through to the kitchen, where he found Linnie pulling cleaning supplies from the orange crate under the sink. She was kneeling on the floor, and the soles of her bare feet, which were facing him, were gray with dirt. “I’m home,” he told her.

“Oh, good. Could you reach down that platter from up top of the icebox? I clean forgot about it! I like to walked off and left it.”

He reached for the platter on the refrigerator and placed it on the counter. “I’ve half a mind to take another load to the house before it gets dark,” he told her. “It would make things that much easier in the morning.”

“Oh, don’t do that. You’ll wear yourself out. Wait for tomorrow when Dodd and them get here.”

“I wouldn’t take the heavy stuff. Just a few boxes and such.”

She didn’t answer. He wished she would get her head out of the orange crate and look at him, but she was all hustle-bustle, so after a minute he left her.

In the living room, the children were piling up empty cartons to build something. Or Merrick was. Redcliffe was still too little to have any plan in mind, but he was thrilled that Merrick was playing with him and he staggered around happily, dragging boxes wherever she told him to. The rug had been rolled up for the move and it gave them an expanse of bare floorboards. “Look at our castle, Daddy,” Merrick said, and Junior said, “Very nice,” and went on back to the bedroom to change out of his good clothes. He always wore his suit when he was giving estimates.

When he returned to the kitchen, Linnie was packing the cleaning supplies in a Duz carton. “Mrs. Abbott’s husband said no to half the features she was wanting,” Junior said. “He went straight down the list: ‘Why’s this cost so much? Why’s this?’ I wished I had known he would do that way before I went to all that trouble with my figures.”

“That’s a shame,” Linnie Mae said. “Maybe she’ll talk to him later and get him to change his mind.”

“No, she was just going along with it. ‘Oh,’ she said, all sad and mournful, each time he crossed something off.”

He waited for Linnie to comment, but she didn’t. She was wrapping a bottle of ammonia in a dish towel. He wished she would look at him. He was starting to feel uneasy.

Linnie Mae wasn’t the type to shout or sulk or throw things when she was mad about something; she would just stop looking at him. Well, she would look if she had some cause to, but she wouldn’t study him. She would speak pleasantly enough, she would smile, she would act the same as ever, and yet always there seemed to be something else claiming her attention. At such times, he surprised himself by his urgent need of her gaze. All at once he would realize how often she did look at him, how her eyes would linger on him as if she just purely enjoyed the sight of him.

He couldn’t think of any reason she would be mad at this moment, though. He was the one who should be mad – and was mad. Still, he hated this feeling of uncertainty. He walked over to stand squarely in front of her, with only the Duz carton between them, and he said, “Would you like to eat at the diner tonight?”

They seldom ate at the diner. It had to be a special occasion. But Linnie didn’t look at him, even so. She said, “I reckon we’ll have to, because I took everything in the icebox over to the house today.”

“You did?” he said. “How come?”

“Oh, Doris was keeping the children so I could get some packing done, and I just thought, ‘Why don’t I visit the new house on my own?’ You know I’ve never done that. So I packed up two bags of food and I caught the streetcar over.”

“We could have put the food on the truck tomorrow,” Junior said. His mind was racing. Had she seen the revarnished swing? She must have. He said, “I don’t know why you thought you had to lug all that by yourself.”

“I just figured I was going anyhow, so I might as well carry something,” she said. “And this way we can have breakfast there tomorrow, out of the way of the men.”

She was focusing on the canister of Bon Ami that she was setting upright in one corner of the carton.

“Well,” he said, “how’d the place look to you?”

“It looked okay,” she said. She fitted a long-handled scrub brush into another corner. “The door sticks, though.”

“Door?”

“The front door.”

So she had definitely gone in through the front. Well, of course she had, walking from the streetcar stop.

He said, “That door doesn’t stick!”

“You push down the thumb latch and it won’t give. For a moment I figured I just hadn’t unlocked it right, but when I pulled the door toward me a little first and then pushed down, it gave.”

“That’s the weather stripping,” Junior said. “It’s got good thick weather stripping, is why it does like that. That door does not stick.”

“Well, it seemed to me like it did.”

“Well, it doesn’t.”

He waited. He almost asked her. He almost came straight out and said, “Did you notice the swing? Were you surprised to see it back the way it was? Don’t you have to agree now that it looks better that way?”

But that would be laying himself open, letting her know he cared for her opinion. Or letting her think he cared.

She might tell him the swing looked silly; it was a trying-too-hard copy of a rich person’s swing; he was pretending to be someone he was not.

So all he said was, “You’ll be glad to have that weather stripping when winter comes, believe me.”

Linnie fitted a box of soap flakes next to the Bon Ami. After a moment, he left the room.

Walking to the diner in the twilight, they passed people sitting out on their porches, and everyone – friend or stranger – said “Evening,” or “Nice night.” Linnie said, “I hope the neighbors will say hey to us in the new place.”

“Why, of course they will,” Junior said.

He had Redcliffe riding on his shoulders. Merrick scooted ahead of them on her old wooden Kiddie Kar, propelling it with her feet. She was way too big for it now, but they couldn’t buy her a tricycle on account of the rubber shortage.

“That Mrs. Brill,” Linnie said. “Remember how she’d talk about ‘my’ grocer and ‘my’ druggist? Like they belonged to her! At Christmastime, when she’d drop off our basket: ‘I got the mistletoe from my florist,’ she’d say, and I’d think, ‘Wouldn’t the florist be surprised to hear he’s yours!’ I surely hope our new neighbors aren’t going to talk like that.”

“She didn’t mean it like it sounded,” Junior said. Then he took two long strides ahead of her and turned so that he was walking backwards, looking into her face. “She probably just meant that our florist might not carry mistletoe, but hers did.”

Linnie laughed. “Our florist!” she echoed. “Can you imagine?”

But her eyes were on old Mr. Early, who was hosing down his steps, and she waved to him and called, “How you doing, Mr. Early?”

Junior gave up and faced forward again.

The longest she’d ever stopped looking at him was when she wanted to have a baby and he didn’t. She’d wanted one for several years and he had kept putting her off – not enough money, not the right time – and she had accepted it, for a while. Then finally he had said, “Linnie Mae, the plain truth is I don’t ever want children.” She had been stunned. She had cried; she had argued; she had claimed he only felt that way on account of what had happened with his mother. (His mother had died in childbirth, taking the baby with her. But that had nothing to do with it. Really! He had long ago put that behind him.) And then by and by, Linnie had just seemed to stop savoring the sight of him. He had to admit that he had felt the lack. He’d always known, even without her saying so, that she found him handsome. Not that he cared about such things! But still, he had been conscious of it, and now something was missing.

He had been the one to give in, that time. He had lasted about a week. Then he’d said, “Listen. If we were to have children …” and the sudden, alerted sweep of her eyes across his face had made him feel the way a parched plant must feel when it’s finally given water.

Over supper he talked to Merrick and Redcliffe about how they would have their own rooms now. Redcliffe was busy squeezing the skins off his lima beans, but Merrick said, “I can’t wait. I hate sharing my room! Redcliffe smells like pee every morning.”

“Be nice, now,” Linnie Mae told her. “You used to smell like pee, too.”

“I never!”

“You did when you were a baby.”

“Redcliffe is a baby!” Merrick teased Redcliffe in a singsong.

Redcliffe popped another lima bean.

“Who wants ice cream?” Junior asked.

Merrick said, “I do!” and Redcliffe said, “I do!”

“Linnie Mae?” Junior asked.

“That would be nice,” Linnie Mae said.

But she was turned in Redcliffe’s direction now, wiping lima-bean skins off his fingers.

It was their custom to listen to the radio together after the children had gone to bed – Linnie sewing or mending, Junior reviewing the next day’s work plan. But the living room was a jumble now, and the radio was packed in a carton. Linnie said, “I guess maybe I’ll head off to bed myself,” and Junior said, “I’ll be up in a minute.”

He spent a while packing his business papers for the move, and then he turned out the lights and went upstairs. Linnie had her nightgown on but she was still puttering around the bedroom, putting the items on top of the bureau into drawers. She said, “Are you going to need the alarm clock?”

“Naw, I’m bound to wake on my own,” he said.

He stripped to his underthings and hung his shirt and overalls on the hooks inside the closet door, although as a rule he would have just slung them onto the chair since he’d be wearing them tomorrow. “Our last night in this house, Linnie Mae,” he said.

“Mm-hmm.”

She folded the bureau scarf and laid it in the top drawer.

“Our last night in this bed, even.”

She crossed to the closet and gathered a handful of empty hangers.

“But I can still visit you in your new bed,” he said, and he gave her rear end a playful tap as she walked past him.

She made a subtle sort of tucking-in move that caused his tap to glance off of her, and she bent to fit the hangers into the bureau drawer.

“Junior,” she said, “tell me the truth: where did that burglar’s kit come from?”

“Burglar’s kit? What burglar’s kit?”

“The one in Mrs. Brill’s sunroom. You know the one I mean.”

“I don’t have the slightest idea,” he said.

He got into bed and pulled the covers up, turned his face to the wall and closed his eyes. He heard Linnie cross to the closet again and scrape another collection of hangers along the rod. Outside the open window a car passed – an older model, from the putt-putt sound of it – and somebody’s dog started barking.

A few minutes later he heard her pad toward the bed, and he felt her settling onto her side of it. She lay down and then turned away from him; he felt the slight tug of the covers. The lamp on her nightstand clicked off.

He wondered how she had reacted when she first saw the revarnished swing. Had she blinked? Had she gasped? Had she exclaimed aloud?

He had a vision of her as she must have looked trudging up the walk with her two bags of food: Linnie Mae Inman in her country-looking straw hat with the wooden cherries on the brim, and her cotton dress with the cuffed short sleeves that exposed her scrawny arms and roughened elbows. It made him feel … hurt, for some reason. It hurt his feelings on her behalf. All alone, she would have been, threading up the hill beneath those giant poplars toward that wide front porch. All alone she must have figured out the streetcar, which was one she hadn’t taken before – she only ever went down to the department stores on Howard Street – and she’d decided which way to turn at the corner where she got off, and she had no doubt tilted her chin pridefully as she walked past the other houses in case the neighbors happened to be watching.

He opened his eyes and shifted onto his back. “Linnie Mae,” he said toward the ceiling. “Are you awake?”

“I’m awake.”

He turned so his body was cupping hers and he wrapped his arms around her from behind. She didn’t pull away, but she stayed rigid. He took a deep breath of her salty, smoky smell.

“I ask your pardon,” he said.

She was silent.

“I’m just trying so hard, Linnie. I guess I’m trying too hard. I’m just trying to pass muster. I just want to do things the right way, is all.”

“Why, Junior,” she said, and she turned toward him. “Junie, honey, of course you do. I know that. I know you, Junior Whitshank.” And she took his face between her hands.

In the dark he couldn’t see if she was looking at him or not, but he could feel her fingertips tracing his features before she put her lips to his.

Dodd McDowell and Hank Lothian and the new colored man were due to arrive at eight – Junior let his men start a little late when they worked on weekends – so at seven, he drove Linnie and the children to the house along with some boxes of kitchen things. The plan was that she would stay there unpacking while he went back to help load the furniture.

As they were pulling into the street, Doris Nivers from next door came out in her housecoat, carrying a potted plant. Linnie rolled down her window and called, “Morning, Doris!”

“I’m just trying not to bawl my eyes out,” Doris told her. “The neighborhood won’t feel the same! Now, this plant might not look to you like much, but it’s going to flower in a few weeks and give you lots of beautiful zinnias.”

“Zeenias,” she pronounced it, in the Baltimore way. She passed the plant through the window to Linnie, who took it in both hands and sank her nose into it as if it were blooming already. “I won’t say ‘Thank you,’ ” she told Doris, “because I don’t want to kill it off, but you know I’m going to think of you every time I look at it.”

“You just better had! Bye, kiddos. Bye, Junior,” Doris said, and she took a step backward and waved.

“So long, Doris,” Junior said. The children, who were still in a just-awakened stupor, merely stared, but Linnie waved and kept her head out the window till their truck had turned the corner and Doris was out of sight.

“Oh, I’m going to miss her so much!” Linnie told Junior, pulling her head in. She leaned past Redcliffe to set the plant on the floor between her feet. “I feel like I’ve lost my sister or something.”

“You haven’t lost her. You’re moving two miles away! You can invite her over any time you like.”

“No, I know how it will be,” Linnie said. She blotted the skin beneath her right eye and then her left eye with an index finger. “Suppose I ask her to lunch,” she said. “I ask her and Cora Lee and them. If I give them something fancy to eat they’ll say I’m getting above myself, but if I give them what I usually do they’ll say that I must not think they’re as high-class as my new neighbors. And they won’t invite me back; they’ll say their houses wouldn’t suit me anymore, and bit by bit they’ll stop accepting my invitations and that will be the end of it.”

“Linnie Mae. It is not a capital crime to move to a bigger place,” Junior said.

Linnie Mae reached into her pocket to pull out a handkerchief.

When he drew to a stop in front of the house, she asked, “Shouldn’t we park around back? What about all we’ve got to carry?”

“I thought we’d have a bite of breakfast first,” he said.

Which made no sense, really – they could eat breakfast just as well if he had parked in back – but he wanted to give their arrival the proper sense of occasion. And Linnie might have guessed that, because she just said, “Well. See there? Now you’re glad I brought that food over.”

While she was gathering herself together – hunting her purse on the floor and bending for her plant – he came around and opened the door for her. She looked surprised, but she passed Redcliffe to him, and then she stepped down from the truck. “Come on, kids,” Junior said, setting Redcliffe on the ground. “Let’s make our grand entrance.” And the four of them started up the walk.

Under the shelter of the trees the front of the house didn’t get the morning sun, but that just made the deep, shady porch seem homier. And the honey-gold of the swing, visible now through the balustrade, gladdened Junior’s heart. He had to stop himself from saying to Linnie, “See? See how right it looks?”

When his eyes caught a flash of something blue, he blamed it on the power of suggestion – a crazy kind of aftereffect of all that had happened before.

Then he looked again, and he froze.

A trail of blue paint traveled down the flagstones – a scattered explosion of blue starting directly in front of the steps and then collecting itself to proceed in a wide band down the walk, narrowing to a trickle as it approached his shoes. It was so thick that it almost seemed he could peel it up with his fingers; it was so shiny that he instinctively drew back his nearest foot, although on closer inspection he saw that it had dried. And anyone – or was it only Junior? – could tell from the briefest glance that it had been flung in anger.

Linnie, meanwhile, had disengaged her hand from his and gone ahead, calling, “Slow down, Merrick! Slow down, Redcliffe! Your daddy needs to unlock the door!”

It would take his men days to remove this. It would take abrasives and chemicals – offhand, he wasn’t even sure what kind – and scrubbing and scraping and grinding; and still, traces of blue would remain. Really the blue would never come off, not completely. There would be microscopic dots of blue in the mortar forever after, perhaps unnoticed by strangers but evident to Junior. He could see his future unreeling before him as clearly as a movie: how he would try one method, try another, consult the experts, lie awake nights, research different solutions like a man possessed, and no doubt end by having to dig the whole thing up and start over. Failing that, the walk would be marked indelibly, engraved with Swedish blue for all time.

And meanwhile Linnie Mae was heading up the walk with her spine very straight and her hat very level, all innocent and carefree. Not even a glance backward to find out how he was taking this.

Why had he worried for one second about abandoning her at the train station? She would have done just fine without him! She would do just fine anywhere.

She had set out to snag him and succeeded without half trying. She had weathered five years of public scorn entirely on her own. She’d ridden who knows how many trains on who knows how many branch lines and tracked him down without a hitch. He saw her craning her neck by the pickup lane; he saw her ringing strange ladies’ doorbells with her suitcase and her hobo bundle; he saw her laughing in the kitchen with Cora Lee. He saw her yanking his whole life around the way she would yank a damp sweater that she had pulled out of the washtub to block and reshape.

He supposed he should be glad of that last part.

Redcliffe stumbled but righted himself. Merrick was running ahead. “Wait,” Junior called, because they were nearing the steps now. They all stopped and turned toward him, and he walked faster to catch up. Birds were singing in the poplars above him. Small white butterflies were flitting in the one patch of sun. When he reached Linnie’s side he took hold of her hand, and the four of them climbed the steps. They crossed the porch. He unlocked the door. They walked into the house. Their lives began.