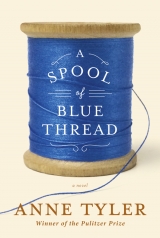

Текст книги "A Spool of Blue Thread"

Автор книги: Anne Tyler

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

She was the bane of his existence. She was a millstone around his neck. That night back in ’31 when he went to collect her from the train station and found her waiting out front – her unevenly hemmed gray coat too skimpy for the Baltimore winter, her floppy, wide-brimmed felt hat so outdated that even Junior could tell – he’d had the incongruous thought that she was like mold on lumber. You think you’ve scrubbed it off but one day you see it’s crept back again.

He had considered not going to collect her. She had telephoned him at his boardinghouse, and when he heard that confounded “Junie?” (nobody else called him that) in her stringy high voice he’d known instantly who it was and his heart had sunk like a stone. He’d wanted to slam the earpiece onto the hook again. But he was caught. She had his landlady’s phone number. Lord only knew how she’d gotten it.

He said, “What.”

“It’s me! It’s Linnie Mae!”

“What do you want?”

“I’m here in Baltimore, can you believe it? I’m at the railroad station! Could you come pick me up?”

“What for?”

There was the tiniest pause. Then, “What for?” she asked. All the bounce had gone out of her voice. “Please, Junie, I’m scared,” she said. “There’s a whole lot of colored folks here.”

“Colored folks won’t hurt you,” he said. (They didn’t have any colored back home.) “Just pretend you don’t see them.”

“What am I going to do, Junior? How am I going to find you? You have to come and get me.”

No, he did not have to come and get her. She didn’t have the least little claim on him. There was nothing between them. Or there was only the worst experience of his life between them.

But he was already admitting to himself that he couldn’t just leave her there. She’d be as helpless as a baby chick.

Besides, a little sprig of curiosity had begun to poke up in his mind. Someone from home. Here in Baltimore!

The fact was, there weren’t a whole lot of people he knew to talk to in Baltimore.

So, “Well,” he said finally. “You be waiting, then.”

“Oh, hurry, Junie!”

“Wait out front. Go out the main door and watch for my car out front.”

“You have a car?”

“Sure,” he said. He tried to sound offhand about it.

He went back upstairs for his jacket. When he came down again, his landlady cracked her parlor door open and poked her head out. She had hair of a peculiar gold color with curls he couldn’t quite understand: each as round and flat as a penny, plastered to her temples. “Everything all right, Mr. Whitshank?” she asked, and Junior said, “Yes, ma’am,” and crossed the foyer in two strides and was gone.

Now, Junior’s belongings back then wouldn’t have filled a decent-size suitcase, but he did own a car of sorts: a 1921 Essex. He’d bought it off another carpenter for thirty-seven dollars when they all lost their jobs at the start of hard times. He’d justified the expenditure on the grounds that a car would help in his hunt for work, and that had turned out to be the case although he hadn’t bargained on its many crotchets and breakdowns. It crossed his mind, as he was coaxing the cold engine to life, that he could have told Linnie to take a streetcar instead. But he knew that would have been beyond her. Streetcars were foreign to her. She’d have bungled it somehow. He couldn’t even picture her making that train trip by herself, because she would have had to transfer in Washington, D.C., he knew, not to mention a whole lot of smaller stations before then.

He lived in the mill district, north of the station – a good distance north, in fact. To go south he cut east to St. Paul and then chugged between the rows of dimly lit houses, leaning forward from time to time to wipe the fog of his breath off the windshield. At length he passed the train station and turned right, onto the paving that crossed in front of its important-looking columns. He spotted Linnie immediately – the only person out there, her white, anxious face swiveling from side to side. But he didn’t stop for her. Without consciously deciding to, he gathered speed and drove on. He took another right onto Charles Street and headed for home, but halfway up the first block he started picturing how her forehead would have smoothed when she caught sight of him, how relieved she would have looked, how experienced and knowing he would have seemed arriving in his red Essex. He circled back around and passed the important columns again, and this time he veered into the pickup lane. Slowing to a stop, he watched as she snatched up her cardboard suitcase and hurried to open the passenger door.

“Did you drive past me once before?” she demanded as soon as she was seated.

Just like that, he lost his advantage.

“I was getting ready for bed,” he said, and his voice came out sounding whiny, somehow. “I’m half asleep.”

She said, “Oh, poor Junie, I’m sorry,” and she leaned across her suitcase to kiss his cheek. Her lips were warm, but she gave off the smell of frost. Also, underneath, another smell, one he associated with home: something like fried bacon. It weighed down his spirits.

But after he started driving, putting the Essex through its gears, he began to feel in control again. “I don’t know why you’re here,” he told her.

“You don’t know why I’m here?” she said.

“And I don’t know where I’m going to take you. I don’t have the money to put you up in a hotel. Unless you have money.”

If she did, she wasn’t letting on. “You’re taking me home with you,” she told him.

“No, I’m not. My landlady only rents to men.”

“You could slip me in, though.”

“What: slip you into my room?”

She nodded.

“Not on your life,” he said.

But he kept driving in the direction of the boardinghouse, because he didn’t know what else to do.

They reached an intersection, and he braked and turned to look at her. Five years, just about, hadn’t changed her in the least; she might still be thirteen. Her face still seemed drawn too tight, as if she didn’t have quite enough skin to go around, and her lips were still thin and colorless. It was as if she had frozen in time the day he left. He didn’t know why he had ever found her attractive. But clearly she couldn’t tell what he was thinking, because she smiled and ducked her chin and looked up at him sideways and said, “I wore those shoes you like so much.”

What shoes could those be? He didn’t remember any shoes. He glanced down at her feet and saw dark, high-heeled pumps with ankle straps, so blocky and oversized that her shins looked as slender as clover stems.

“How did you find out where I was?” he asked her.

She stopped smiling. She straightened and stood her big purse on the tip end of her knees.

“Well,” she said, and she gave a sharp nod. (He’d forgotten how she used to do that. It said, “Down to business.” It said, “Let me handle this.”) “Four days ago was my birthday,” she said. “I’m eighteen years old now.”

“Happy birthday,” he said dully.

“Eighteen, Junie! Legal age!”

“Legal age is twenty-one,” he told her.

“Well, for voting, maybe … and I already had my suitcase packed; I already had my money saved. I earned it picking galax every fall since you left. But I laid low till I was eighteen, so nobody could stop me. Then the day after my birthday, I had Martha Moffat drive me to the Parryville lumberyard and I asked the fellows there if they could say where you’d gone off to.”

“You asked the whole yard?” he said, and she nodded again.

He could just picture how that must have looked.

“And this one fellow, he told me you might could have headed north. He said he remembered you coming in one day, wondering if anyone knew where this carpenter was they called Trouble, on account of his name was Trimble. And they told you Trouble’d gone to Baltimore, so maybe that’s where you went, this fellow said, looking for work. So I got Martha to ride me to Mountain City and I bought a ticket to Baltimore.”

Junior was reminded of those movie cartoons where Bosko or someone steps off a cliff and doesn’t even realize he’s standing on empty space. Had Linnie not grasped the chanciness? He could have moved on years ago. He could be living in Chicago now, or Paris, France.

It seemed to him all at once a kind of failure that he was not; that here he still was, all this time afterward. And that she had somehow known he would be.

“Martha Moffat’s name is Shuford now,” Linnie was saying. “Did you know Martha got married? She married Tommy Shuford, but Mary Moffat’s still single and it’s like to kill her soul, you can tell. She acts mad at Martha all the time about every little thing. But then they never did get along as good as you’d expect.”

“As well,” he said.

“What?”

He gave up.

They were traveling through downtown, with the buildings set cheek to jowl and the streetlights glowing, but Linnie barely glanced out the window. He had thought she would be more impressed.

“When I got off the train in Baltimore,” she said, “I went straight to the public telephone and I looked for you in the book, and when I couldn’t find you I called everybody named Trimble. Or I would have, except Trouble’s first name turned out to be Dean and that came pretty soon in the alphabet. And he said you had looked him up, and he’d told you where you might could find work, but he didn’t know if they’d hired you or not and he couldn’t say where you were living, unless you were still at Mrs. Bess Davies’s where a lot of workingmen board at when they first come north.”

“You should get a job with Pinkerton’s,” Junior said. He wasn’t pleased to hear how easy he’d been to find.

“I worried you had moved by now, found a place of your own or something.”

He frowned. “There’s a depression on,” he said. “Or haven’t you heard?”

“It’s fine with me if you live in a boardinghouse,” she said, and she patted his arm. He jerked away, and for a while after that she was quiet.

When they reached Mrs. Davies’s street he parked some distance from the house, at the darker end of the block. He didn’t want anyone seeing them.

“Are you glad I’m here?” Linnie asked him.

He shut off the engine. He said, “Linnie—”

“But my goodness, we don’t have to go into everything all at once!” Linnie said. “Oh, Junior, I’ve missed you so! I haven’t once looked at a single other fellow since you left.”

“You were thirteen years old,” Junior said.

Meaning, “You’ve spent all the time since you were thirteen never having a boyfriend?”

But Linnie, misunderstanding, beamed at him and said, “I know.”

She picked up his right hand, which was still resting on the gearshift knob, and pressed it between both of hers. Hers were very warm, despite the weather, so that his must have struck her as cold. “Cold hands, warm heart,” she told him. Then she said, “And so here I am, about to spend the first full night with you I’ve ever had in my life.” She seemed to be taking it for granted that he had decided to slip her in after all.

“The first and only night,” he told her. “Then tomorrow you’re going to have to find yourself someplace else. It’s risky enough as it is; if Mrs. Davies caught wind of you, she’d put us both out on the street.”

“I wouldn’t mind that,” Linnie said. “Not if I was with you. It would be romantic.”

Junior withdrew his hand and heaved himself out of the car.

At the foot of the front steps he made her wait, and he opened the front door silently and checked for Mrs. Davies before he signaled Linnie to come on in. Every creak of the stairs as he and Linnie climbed made him pause a moment, filled with dread, but they made it. Arriving on the third floor – the servants’ floor, he’d always figured, on account of its tiny rooms with their low, slanted ceilings – he gave a jab of his chin toward a half-open door and whispered, “Bathroom,” because he didn’t want her popping in and out of his room all night. She wriggled her fingers at him and disappeared inside, while he continued on his way with her suitcase. He left his door cracked a couple of inches, the light threading out onto the hall floorboards, until she slipped inside and shut it behind her. She was carrying her hat in one hand and her hair was damp at the temples, he saw. It was shorter than when he’d first known her. It used to hang all the way down her back, but now it was even with her jaw. She was breathless and laughing slightly. “I didn’t have my soap or a facecloth or towel or anything,” she said. Even though she was whispering, it was a sharp, carrying whisper, and he scowled and said, “Ssh.” In her absence he’d stripped to his long johns. There was a small, squarish armchair in the corner with a mismatched ottoman in front of it – the only furniture besides a narrow cot and a little two-drawer bureau – and he settled into it as best he could and arranged his winter jacket over himself like a blanket. Linnie stood in the middle of the room, watching him with her mouth open. “Junie?” she said.

“I’m tired,” he said. “I have to work tomorrow.” And he turned his face away from her and closed his eyes.

He heard no movement at all, for a time. Then he heard the rustle of her clothing, the snap of two suitcase clasps, more rustling. The louder rustle of bedclothes. The lamp clicked off, and he relaxed his jaw and opened his eyes to stare into the dark.

“Junior?” she said.

He could tell she must be lying on her back. Her voice had an upward-floating quality.

“Junior, are you mad at me? What did I do wrong?”

He closed his eyes.

“What’d I do, Junior?”

But he made his breath very slow and even, and she didn’t ask again.

11

WHAT LINNIE HAD DONE WRONG:

Well, for starters, she’d not told him her age. The first time he saw her she was sitting on a picnic blanket with the Moffat twins, Mary and Martha, both of them seniors in high school, and he had just assumed that she was the same age they were. Stupid of him. He should have realized from her plain, unrouged face, and her hair hanging loose down her back, and the obvious pride she took in her new grown-upness – most especially in her breasts, which she surreptitiously touched with her fingertips from time to time in a testing sort of way. But they were such large breasts, straining against the bodice of her polka-dot dress, and she was wearing big white sandals with high heels. Was it any wonder he had imagined she was older? Nobody aged thirteen wore heels that Junior knew of.

He had come with Tillie Gouge, but only because she’d asked him. He didn’t feel any particular obligation to her. He picked up a molasses lace cookie from the picnic table laden with foods, and he walked over to Linnie Mae. Bending at the waist – which must have looked like bowing – he offered the cookie. “For you,” he said.

She lifted her eyes, which turned out to be the nearly colorless blue of Mason jars. “Oh!” she said, and she blushed and took it from him. The Moffat twins became all attention, sitting up very straight and watching for what came next, but Linnie just lowered her fine pale lashes and nibbled the edge of the cookie. Then, one by one, she licked each of her fingers in turn. Junior’s fingers were sticky too – he should have chosen a gingersnap – and he wiped them on the handkerchief he drew from his pocket, but meanwhile he was looking at her. When he’d finished, he offered her the handkerchief. She took it without meeting his eyes and blotted her fingers and handed it back, and then she bit off another half-moon of cookie.

“Do you belong to Whence Baptist?” he asked. (Because this picnic was a church picnic, given in honor of May Day.)

She nodded, chewing daintily, her eyes downcast.

“I’ve never been here before,” he said. “Want to show me around?”

She nodded again, and for a moment it seemed that that might be the end of it, but then she rose in a flustered, stumbling way – she’d been sitting on the hem of her dress and it snagged briefly on one of her heels – and walked off beside him, not so much as glancing at the Moffat twins. She was still eating her cookie. Where the churchyard met the graveyard she stopped and switched the cookie to her other hand and licked off her fingers again. Once again he offered his handkerchief, and once again she accepted it. He thought, with some amusement, that this could go on indefinitely, but when she’d finished blotting her fingers she placed her cookie on the handkerchief and then folded the handkerchief carefully, like someone wrapping a package, and gave it to him. He stuffed it in his left pocket and they resumed walking.

If he thought back on that scene now, it seemed to him that every detail of it, every gesture, had shouted “Thirteen!” But he could swear it hadn’t even crossed his mind at the time. He was no cradle robber.

Yet he had to admit that the moment when he’d taken notice of her was the moment she had touched her own breasts. At the time it had seemed seductive, but on second thought he supposed it could be read as merely childish. All she’d been doing, perhaps, was marveling at their brand-new existence.

She walked ahead of him through the cemetery, her skinny ankles wobbling in her high-heeled shoes, and she pointed out her daddy’s parents’ headstones – Jonas Inman and Loretta Carroll Inman. So she was one of the Inmans, a family known for their stuck-up ways. “What’s your first name?” he asked her.

“Linnie Mae,” she said, blushing again.

“Well, I am Junior Whitshank.”

“I know.”

He wondered how she knew, what she might have heard about him.

“Tell me, Linnie Mae,” he said, “can I see inside this church of yours?”

“If you want,” she said.

They turned and left the cemetery behind, crossed the packed-earth yard and climbed the front steps of Whence Cometh My Help. The interior was a single dim room with smoke-darkened walls and a potbellied stove, its few rows of wooden chairs facing a table topped with a doily. They came to a stop just inside the door; there was nothing more to see.

“Have you got religion?” he asked her.

She shrugged and said, “Not so much.”

This caused a little hitch in the flow, because it wasn’t what he’d expected. Evidently she was more complicated than he had guessed. He grinned. “A girl after my own heart,” he said.

She met his gaze directly, all at once. The paleness of her eyes startled him all over again.

“Well, I reckon I should go pay some heed to the gal I came here with,” he said, making a joke of it. “But maybe tomorrow evening I could take you to the picture show.”

“All right,” she said.

“Where exactly do you live?”

“I’ll just meet you at the drugstore,” she said.

“Oh,” he said.

He wondered if she was ashamed to show him to her family. Then he figured the hell with it, and he said, “Seven o’clock?”

“All right.”

They stepped back out into the sunlight, and without another glance she left him on the stoop and made a beeline for the Moffat twins. Who were watching, of course, as keen as two sparrows, their sharp little faces pointing in Junior and Linnie’s direction.

They had been seeing each other three weeks before her age came out. Not that she volunteered it; she just happened to mention one night that her older brother would be graduating tomorrow from eighth grade. “Your older brother?” he asked her.

She didn’t get it, for a moment. She was telling him how her younger brother was smart as a whip but her older brother was not, and he was begging to be allowed to drop out now and not go on to the high school in Mountain City the way their parents were expecting him to. “He’s never been one for the books,” she said. “He likes better to hunt and stuff.”

“How old is he?” Junior asked her.

“What? He’s fourteen.”

“Fourteen,” Junior said.

“Mm-hmm.”

“How old are you?” Junior asked.

She realized, then. She colored. She tried to carry it off, though. She said, “I mean he’s older than my other brother.”

“How old are you?” he said again.

She lifted her chin and said, “I’m thirteen.”

He felt he’d been kicked in the gut.

“Thirteen!” he said. “You’re just a … you’re not but half my age!”

“But I’m an old thirteen,” Linnie said.

“Good God in heaven, Linnie Mae!”

Because by now, they were doing it. They’d been doing it since their third date. They didn’t go to movies anymore, didn’t go for ice cream, certainly didn’t meet up with friends. (What friends would those have been, anyhow?) They just headed for the river in his brother-in-law’s truck and flung a quilt any old which way under a tree and rushed to tangle themselves up in each other. One night it poured and it hadn’t stopped them for a minute; they lay spread-eagled when they were finished and let the rain fill their open mouths. But this wasn’t something he had talked her into. It was Linnie who had made the first move, drawing back from him in the parked truck one night and shakily, urgently tearing open her button-front dress.

He could be arrested.

Her father grew burley tobacco, and he owned his land outright. Her mother came from Virginia; everyone knew Virginians thought they were better than other people. They would call the sheriff on him without the least hesitation. Oh, Linnie had been so foolish, so infuriatingly brainless, to meet him like that at the drugstore in the middle of her hometown wearing her dress-up dress and her high-heeled shoes! Junior lived over near Parry ville, six or eight miles away, so maybe no one who had seen them together in Yarrow knew him, but it couldn’t have escaped their notice that he was a grown man, most often in shabby clothes and old work boots with a day or two’s worth of beard, and it wouldn’t be that hard to find out his name and track him down. He asked Linnie, “Did you tell anybody about us?”

“No, Junior, I swear it.”

“Not the Moffat twins or anyone?”

“No one.”

“Because I could go to jail for this, Linnie.”

“I didn’t tell a soul.”

He made up his mind to stop seeing her, but he didn’t say so right then because she would get all teary and beg him to change his mind. There was something a little bit hanging-on about Linnie. She was always talking about this great romance of theirs, and telling him she loved him even though he never mentioned love himself, and asking him if he thought so-and-so was prettier than she was. It was because it was all so new to her, he guessed. God, he’d saddled himself with an infant. He couldn’t believe he had been so blind.

They folded the quilt and they got in the truck and Junior drove her back to town, not saying a word the whole ride although Linnie Mae chattered nonstop about her brother’s upcoming graduation party. When he drew up in front of the drugstore, he said he couldn’t meet her the following night because he’d promised to help his father with a carpentering job. She didn’t seem to find it odd that he would be carpentering at night. “Night after that, then?” she said.

“We’ll see.”

“But how will I know?”

“I’ll get word to you when I’m free,” he said.

“I’m going to miss you like crazy, Junior!”

And she flung herself on him and wrapped her arms around his neck, but he pulled her arms off him and said, “You’d better go on, now.”

Of course he didn’t get word to her. (He didn’t know how she had thought he would do that, seeing as he’d said they couldn’t tell anyone else.) He stayed strictly within his own territory – two acres of red clay outside Parryville bounded by a rickrack fence, in the three-room cabin he shared with his father and his last unmarried brother.

As it happened, the three of them did have work that week, replacing the roof on a shed for a lady down the road. They would set out early every morning in the wagon, with a tin bucket of buttermilk and a hunk of cornpone for their lunch, and they’d turn their mule loose in Mrs. Honeycutt’s pasture and go up on the roof to work all day in the blazing sun. By evening Junior would be so bushed that it was all he could do to force supper down. (His brother Jimmy had taken over the cooking after their mother died – just fried up whatever meat they’d last killed, using the half-inch of white grease that waited permanently in the skillet on the wood stove.) They’d be in bed by eight or eight thirty, workingmen’s hours. Three days in a row they did that, and Junior didn’t give more than a thought or two to Linnie Mae. Once Jimmy asked if he wanted to go into town after supper and see if they could find any girls, and Junior said, “Nah,” but it wasn’t on account of Linnie. It was just that he was too beat.

Then they finished with the roof, and they didn’t have anything else lined up. Junior spent the next day at home, but he was bored out of his mind and his father was acting ornery, so he figured maybe the next morning he would walk on down to the lumberyard and look for work. They were used to having him come and go there; they could generally use a hand.

He was sitting out on the stoop with the dogs, smoking a cigarette – the twilight still at that stage where it’s transparent, the fireflies just beginning to turn on and off in the yard – when a car he didn’t know pulled in, a beat-up Chevrolet driven by a fellow in a seed-store cap. And a girl jumped out the front passenger door and walked over to him, saying, “Hey, Junior.” One of the Moffat twins. The dogs raised their heads but then settled their chins on their paws again. “Hey back,” Junior said, not using a name because he didn’t know which one she was. She handed him a piece of white paper and he unfolded it, but it was hard to read in the dusk. “What’s this?” he asked.

“It’s from Linnie Mae.”

He held it up to the faint lantern-light that was coming through the screen door. “Junior, I need to talk to you,” he read. “Let the Moffats give you a ride to my house.”

He got a lump of ice in his chest. When a girl said she needed to talk … oh, Lord. Part of him was already trying to figure out where to run, how to get away before she delivered the news that would trap him for life. But the Moffat twin said, “You coming?”

“What: now?”

“Now,” she said. “We’ll ride you over.”

He stood up and stepped on his cigarette. “Well,” he said. “All right.”

He followed her to the car. It was a closed car with four doors, and she got into the front and left him to settle in the rear beside the other twin, who said, “Hey, Junior.”

“Hey,” he said.

“You know our brother Freddy.”

“Hey, Freddy,” he said. He didn’t recall ever meeting him. Freddy just grunted, and then shifted gears and pulled out of the yard and set off down Seven Mile Road.

Junior knew he should make conversation, but all he could think about was what Linnie was going to tell him and what he was going to do about it. What could he do about it? He wasn’t such a bastard as to pretend it hadn’t been him. Although it did cross his mind.

“Linnie’s folks are throwing a party for Clifford tonight,” the first twin said.

“Who’s Clifford?”

“Clifford her brother. He’s finished eighth grade.”

“Oh.”

It seemed to him kind of funny to make such a fuss about eighth grade. When he had finished eighth grade, the big to-do was over why on earth he was set on going on to high school. His father had had it in mind to put him to work, while Junior was thinking that there were still some things he hadn’t learned yet.

Linnie surely didn’t expect him to come to the party, did she? Even she couldn’t be that dumb.

But the twin said, “She’ll be able to slip out of the house easy, being as there’s family around. They’ll never notice she’s gone.”

“Oh,” he said, relieved.

That seemed to use up all their conversational topics.

They cut over on Sawyer Road instead of driving on into Yarrow, so he supposed the Inmans’ farm must lie to the north of town. The smell of fresh manure started drifting through his open window. Sawyer Road was just gravel, and every time the Chevrolet hit a bump the headlamps flickered and threatened to die. It made him nervous. Shoot, everything made him nervous.

He wondered if this was a setup, if they’d have the sheriff ready and waiting at the house. Junior wasn’t liked by the sheriff. As a boy he’d caused a near-accident when he and some friends of his were riding on the back of a wagon and they signaled to the car behind that it was okay to pass. And there’d been a few other situations, over the years.

Freddy turned left where Sawyer Road butt-ended into Pee Creek Road, which was paved and gave a much smoother ride. Some distance after that he turned right, onto a dirt driveway. The house looked big to Junior. It was painted white or light gray and all the windows were lit. A few cars and trucks were parked at different angles on the grass out front. Freddy drove around to the rear, though, where Junior could make out the silhouettes of several dark sheds and barns. “Here we are,” the first twin said.

A shadow moved away from the nearest barn and turned into Linnie, wearing something pale. As she approached the car, Junior asked the Moffats, “Are you-all going to wait for me, or what?”

Before they could answer, Linnie stepped up to his window and whispered, “Junior?”

“Hey,” he said.

She leaned in close, although she couldn’t be thinking he would do anything soft in front of these people, could she? He fended her off by opening his door, nudging her backward. “You-all wait here,” he told the Moffats. “I’m going to need a ride home.”

Linnie said, “Thanks, Freddy. Hey, Martha; hey, Mary.”

“Hey, Linnie,” the twins said in chorus.

Junior stepped out of the car and shut the door behind him, and immediately Freddy shifted into reverse and started backing up. “Where’re they going?” Junior asked Linnie.

“Oh, off somewheres, I guess.”

“How am I getting home?”

“They’ll be back! Come on.”

She was leading him toward the barn she’d come out of, gripping him by the hand. He resisted. “I’m not going to be but a minute,” he said. “They should have stayed.”

“Come on, Junior. Someone will see you!”

He gave up and followed her into the barn, which was pitch-dark once she had shut the door behind them. “Let’s go up in the loft,” she whispered.

But that didn’t feel right. You could be cornered, in a loft. “We can talk down here,” he said. “I can’t stay long. I need to get home. Are you sure the Moffats know to come for me? Why’d you tell them about us? You swore you wouldn’t tell a soul.”

“I didn’t! Just the twins. They think it’s romantic. They’re real happy for us.”