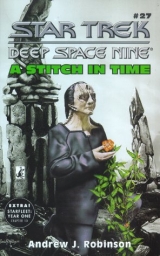

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“What do you think it is?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I’ve heard of a student being asked to leave–it happens often. But never ‘reassigned.’ Who else was at your hearing?”

Simultaneously, I realized that I should not be telling her any of this–and Charaban appeared. He stood behind Palandine. She saw my change of focus and turned. She shook her head.

“Not now, Barkan,” she told him.

“What better time? This is the opportunity, so we take it,” he explained to her. I didn’t know what they were talking about, but I strongly felt the need to be prepared for anything. Especially when Charaban spoke of taking an opportunity.

“Hello, Lubak. Is it still Ten or are you number One?” he inquired.

“My name is Elim Garak,” I replied.

“Yes, I know that,” he laughed. “But is it you or is it Eight Lubak that I have to keep my eye on now?” It was the appearance of warmth that made his charm so attractive. A part of me wanted to tell him everything, to challenge the duplicity of his negative evaluation, but the clarity I found in the Lower Prefect’s office was still with me. Looking at him, I was reminded how Palandine had taught me to smile when I asked questions.

“You have to watch both of us, Barkan.”

“Yes, One and Two. Of course. But who makes the final decisions? Whose thinking do I pit mine against?” he challenged. He assumed that he had some kind of advantage and he pressed it. I saw three openings for attack. He saw my stance and prudently covered the openings.

“I think it’s you, Elim.” He countered with another stance.

“He’s leaving Bamarren today,” Palandine told him. She was also telling him something else. Charaban maintained his stance and never took his eyes off me, but his expression changed.

“Why?” If anything, he was even more surprised than Palandine. Even with his treachery, he hadn’t believed that my dismissal from Bamarren was a possibility. This told me that he had had little or nothing to do with my change of fortune. His entire attitude toward me changed. I was no longer an opponent to be engaged and probed for weakness, but a baffling specimen of some lower order. Assuming I had been rejected and sent home, he stepped out of the strategem.

That’s hisweakness, I thought, and said nothing to counter his assumption. After a long moment, when he understood that I was not going to be forthcoming with any details, he moved on.

“So it’s Eight,” he said, dismissing me from his world.

“I don’t think you understand, Barkan. . . .” Palandine began to say.

“It’s not necessary that he understand,” I dismissed him from myworld. “If you don’t mind, I’d like to have a few moments alone with Palandine before I go.” This seemed to amuse him, and he looked at Palandine, who nodded back.

“Certainly,” he said, with a smile that showed how gracious he could be. “Good‑bye . . . Elim Garak. Perhaps we’ll meet someday in the Tarlak Sector.” I understood the kind of circumstances under which he imagined such a meeting would take place–Elim the maintenance worker setting up the dais for a triumphant hero of the Empire. But it was my fault; I had told him everything he wanted to know about my life. All you have to do is smile when you ask. I answered him with a smile of my own.

“Perhaps you should tell him,” he said to Palandine. They held a look before he turned and left. I wanted to ask what, but I waited for her.

“We’re to be enjoined after the Third Level Culmination,” she finally said.

And it all became clear. Of course. Palandine and Barkan had been connected all along. How else could his sudden appearances be explained? She was a vital part of the recruiting process.

“I wanted to tell you. Especially as I got to know you and . . . like you. I’m sorry, Elim.”

I was surprisingly calm. I felt nothing.

“It was important that we win the Competition,” she said.

“We,” I smiled.

“Yes. We. Our lifelines are going to be enjoined, Elim; we’re partners, and our success can only be ensured by our working together.”

“So he told you to recruit me for the Competition,” I said.

“No. That was my idea. When I first met you I knew.”

“Knew what?”

“That you were . . .” She hesitated, carefully maintaining a distance. “. . . Different.”

“Well . . . I suppose I should be honored.” I was working very hard to maintain my own distance.

“I wanted to tell you. But when I realized . . . I didn’t want to hurt you,” she said with a gentleness that rankled me.

“I’m not hurt. Neither one of you can hurt me. I wish you a successful . . . partnership.” I didn’t want to stay any longer; my numbness was beginning to dissolve, and I couldn’t trust myself to control whatever was emerging. I made an awkward bow–a pathetic attempt to be proper–and started to leave.

“Please, Elim.” She stopped me. “I meant it when I said I needed a friend. I could talk to you. I’ll always consider you my friend.”

“And Barkan? Is he also my friend? Should I accept the way he treated me–used me–as friendship?” The numbness was gone, which only made the pain of losing her much worse.

“Barkan is ambitious. I wanted you on the council, but he felt that it would only give you an advantage when you–inevitably–challenged him for the leadership. He couldbe your friend someday, Elim.” I laughed, too loudly, and she flared in response. “You’re so naпve. You still don’t know what this is all about, do you?”

“I wonder if you’re not the one. . . .” I stopped. I was afraid that once I started to relate the details of his treachery I wouldn’t be able to contain the rage that was spreading to every part of my body like a deadly disease.

“I love him, Elim. And I’m also ambitious. I want what he wants. You’ll understand this when you find someone to share your. . . .”

“I have to go.” I shut myself off like a closing worm‑hole. “Good‑bye, Palandine.” I turned and left. I am number One, I kept reminding myself.

* * *

Eight, who was now designated the number One of Lubak, helped me clean my area. We said very little. When everything was done, I stood in front of my compartment.

“Let me show you something,” I said. He moved next to me. I took Mila from her sandy home. At first he didn’t see her, but when I brought my hand close he reacted.

“So that’s what it was,” he said as Mila’s skin rippled and changed coloration to find a suitable disguise. “We knew you had something in there, but after what you did to Three nobody was going to try to find out again.”

“He’s the reason I succeeded in the Wilderness,” I said.

“And in the Competition,” Eight added. He understood what I meant.

“You can beat Charaban.” I lowered my voice to a fierce whisper.

“We’ll see.” Eight replied.

“No, you can. Because you have the very quality that goes right to his weakness. I had to have Mila to learn how to cover my thinking, but even then I walked into his traps. You won’t, and he’ll be forced to make assumptions about you–and they’ll be wrong.” We watched Mila ripple and change. “My name is Elim Garak. I don’t know where I’m being sent, but I hope you’ll remember me as your friend.”

“When I was told today that I was One Lubak, I was honored . . . and afraid that I’d lose you as a friend. Thank you. My name is Pythas Lok.”

Neither one of us ever took our eyes off Mila, who was still trying to blend into his surroundings.

* * *

I had just enough time to complete my last mission at Bamarren. I returned to the Mekar Wilderness with Mila and to the rock formation that was his original home. I found the escarpment where I had hidden myself that first day, and put Mila on the ground in front of the opening. He stood poised and still, various shades of desert playing across his skin. Something powerful was stirring deep inside me, and I began to shake. Mila snapped his head to the side, the way he does when he senses light or heat change. Convulsive waves pushed up from my center and tears filled my eyes, blinding me. I had absolutely no control over what was happening to me. By the time the convulsions subsided and my eyes cleared, Mila had disappeared into the rock‑and‑sand home he came from.

As I hiked back to the Institute, I had the thought that maybe somebody was doing the same thing for me and bringing me back home.

PART II

“Truth is in the eye of the beholder, Doctor. I never tell the truth because I don’t believe there is such a thing . . .”

“You’re not going to tell me.”

“But you don’t need me to tell you, Doctor . . . if you’ll just notice the details. They’re scattered like crumbs . . .”

1

Entry:

I’m afraid that the “invasion” was not all I had hoped for. The Dominion’s grip on Cardassia is as tight as ever, and it’s going to require another, greater concerted effort on the part of the Federation and its allies to loosen that grip. The most significant change is that the wormhole is closed . . . and so is my shop.

And Jadzia is gone. The station is a sadder and grayer place without her. I’m surprised at how keenly I feel her absence. Even though I know that her symbiont has been “joined” with another person . . . well, it’s not the same, is it? Indeed, knowing that Jadzia’s personality is somehow contained along with several others within this other person, I wonder how I would react if we were ever to meet. It would take some preparation on my part. Trills are such a unique race.

But are they? We all–to some degree–contain the memories, traits, fragments of those personalities that came before us. Indeed, perhaps we are even “joined” on a deeper, more spiritual level. The first Hebitians believed this. Each generation is not only succeeded by the next, it is subsumed by it, so that the past is always present and actively involved in creating the future. So in a sense there is no past and future; there is only the present. And I must say that Jadzia’s spark and vibrancy reflected this immediacy.Which is why we were all drawn to her–like moths to a flame.

I must say, however, that Commander Worf’s manner of mourning has completely baffled me. Entombing himself in that ludicrous holosuite program with Vic and his incomprehensible human gibberish . . . those maudlin songs. . . . The doctor has reminded me that these are personal choices, and it’s not for us to judge how one chooses to mourn. Quite so. Who can even begin to understand another’s grief?

“Do you judge people by the clothes they ask you to make?” the doctor asked once. I bit back my response, but the point was well taken. Besides, I’m not making anyone clothes these days. I now spend my time decoding Cardassian military transmissions, some of which are prototypes of codes I created for the Order. Ironic . . . and disturbing. Odo has been charged with the task of gathering the intercepted transmissions and bringing them to me. One day I asked if he wasn’t ever disturbed by the fact that he was at war with his own people. Did he feel a sense of betrayal? As far as he’s concerned, the Founders conducting this war are betraying everything the Great Link stands for, and therefore they must be defeated. I nodded and agreed . . . but I’m still disturbed.

And I hate this work! I’d much rather be sewing.

“What does Tir Remara want with you?” Colonel Kira demanded, ignoring my offer of tea. Immediately an entire picture formed in my head of the scenario her abrupt question suggested: Tir Remara–a spy, perhaps even a changeling, preying upon a lonely Cardassian who was working for the Federation and engaged in top‑secret work.

“She wants to have my children,” I replied with a serious look.

“You can’t be serious,” she managed.

“I’m not. Now do you want this tea or not?”

“No . . . thank you,” she allowed. It was so difficult for her to muster even a sliver of civility with a member of my race.

“Remara and I are friends. Not terribly close. We get together occasionally. We’re curious about each other.” I sipped at my tea. Kira watched me with a cold expression, waiting for me to continue.

“We found we had a mutual friend, and we have come to . . . enjoy each other’s company.”

“What mutual friend?” Kira was puzzled; who or what would a Bajoran and a Cardassian have in common?

“Ziyal,” I replied.

Kira nodded. “Yes, of course.” The mention of her former protйgй’s name reminded her of what weheld in common: a great affection for Ziyal.

“Why are you asking, Colonel?”

“Because Remara has been making inquiries about you, Garak.”

“Really?”

“And if you arefriends, I don’t know why she wouldn’t be asking you directly.”

“Yes.” My mind was racing. “My thoughts as well.Unless, of course . . .”

“What?” Kira asked.

“She’s planning to write a book about me.” Kira didn’t think that was humorous. “Watch her,Garak. And be careful what you tell her.” She left as abruptly as she entered. I smiled at the irony of being told to watch my mouth. What was going on here? Was it Kira’s concern about a possible breach of security? A friendship between a Bajoran and a Cardassian? And if Remara wasn’t writing a book, what did she want this information for?

2

Entry:

“Careful, Elim. These plants have delicate tendrils. Lower them slowly, so they find the holes.”

I took the Edosian orchid from Father and slowly lowered the pale, dangling feelers over the prepared soil. These orchids were his favorite flowers, and somehow he was able to make them grow in this section of the Tarlak Grounds.

“Just hold the plant for a moment directly above–the tendrils will align themselves.” His voice was almost a whisper. “Now watch closely.”

As if they had eyes, the tendrils swayed until they found the openings Father had dug and paused above them.

“Now lower the plant slowly.” I did. When the root ball had settled in the depression, Father immediately filled in the sides with his special mixture, which he claimed was the secret. People would come from distant places to see the Grounds and especially the miracle of Father’s orchids, which had no logical reason to exist in this climate. When someone asked how he was able to grow them in an outside environment, he’d gauge how serious the questioner was and answer accordingly. To those few he judged to be sufficiently patient, he gave a soil sample and some instructions; to the rest he’d smile and say that Tarlak had a secret ideal quality. And it did–but only because Father had made it that way with his care and unlimited patience.

The Grounds was Father’s passion, and when I returned from Bamarren I worked as his assistant while waiting for my next placement. At first it felt odd to be working at these simple and mindless tasks. But I began to notice that Father was now talking to me more, telling me about the various plants and shrubs and flowers. We spent very little time among the monuments and tombs. Gradually, I began to accept the change and even to enjoy the pace of this work. This was probably Father’s intention.

When I first arrived home, Mother and Father accepted the fact that I was no longer a boy. They looked older to me, especially Father, and the changes I had undergone at Bamarren had created a distance between us that we all found awkward.

During this period I never saw Tain. Once I asked Mother how he was, and she replied that as far as she knew he was fine. I occasionally heard footsteps above us and wondered when he’d come back into my life–a question tinged with some anxiety–but Mother and Father never mentioned him, and I went about my own business.

I spent very little time at home. I found a training area nearby where I practiced my sets of martial forms. I was determined not to lose the fine edge of my conditioning.Occasionally, I would be challenged by someone, usually an ex‑soldier or martial student, but they were never strong or accomplished enough to give me a true match. In a short time I found myself conducting an informal class, where I taught a variegated group the rudimentary forms. These classes were far more valuable than fighting outmatched opponents.

Otherwise, I reverted to a solitary existence, waiting for my life to find new purpose and constantly wondering what my friends . . . and enemies . . . were doing at Bamarren. I had ideas about the coming Competition that I wished I could communicate to Pythas, ideas that would ensure Barkan’s humiliation. And there were feelings I had no words for that I wished I could make known to Palandine.

“That’s who he is now, Tolan. He’s a man.” I heard mother’s voice as I approached the opened door to our housing unit after a training session.

“He’s hard, Mila,” Father said.

“He has to be,” she replied.

“But to the point where he’s unreachable?” Father asked. “Where nothing penetrates? How can he express even his basic needs if he’s trapped inside a shell?”

“It’s better this way, Tolan. I know what’s in store for him,” Mother interrupted. There was a momentary silence.

“More Bamarren,” Father said, almost to himself. There was another silence indicating the discussion was over. I decided to take a walk.

The next day, Father and I were weeding and pruning across from the children’s area where mothers and caretakers bring children to play. The adults talked among themselves, worked, or read while the children’s voices created a constant background of musical chatter. We had been working quietly and steadily, but I knew Father wanted to speak. I didn’t know why he hesitated.

“Elim, have we ever spoken about the first Hebitians?” Father broke the silence with a question so strange it almost made me laugh.

“No,” I carefully answered.

“What do you know about them?”

“They were . . . the first peoples . . . before the climatic change.” Our school histories never spent much time talking about the Hebitians. “They had primitive solar technologies. When the rain forests and grasslands were taken over by the deserts, they died off. They couldn’t adapt.”

“That’s what you were taught.” Father barely shook his head. “That’s not what happened, Elim.”

I said nothing. We continued to work as I listened to the children’s voices punctuated by the clipping and raking and digging.

“The only thing that was primitive about the Hebitians is the way we’ve treated them in the historical record.” I stopped working and looked around. This was the first time I had ever heard him challenge received orthodoxy, and my first concern was that no one was listening. Father noticed this and smiled.

“I see your Bamarren education has taken hold. Fertile ground for young minds.” Slowly and painfully, I thought, he raised himself to his full height, stretched, and picked up his bag.

“Let’s have some tea.” He laughed because he knew that the tea he drank, which was brewed from the roots of some shrub, had made me gag the first–and only–time I’d tried it. I had a separate container of the common chobanvariety. We took our containers and settled in a shady place that faced the playing children.

“Look at them. With young minds you can plant anything and it grows into ideas and beliefs.” We watched one child begin to explore beyond the play area until she was intercepted by the caretaker who, judging by her gestures, was explaining why the toddler mustn’t stray.

“The first Hebitians had an advanced culture that was sophisticated on every level, Elim. Yes, it was solar‑based, but they were able to support themselves, and this is what most of the planet looked like.” He waved his tea container to indicate the Grounds. The idea was almost too outlandish for me. Soft and green places are rare on Cardassia.

“It’s hard to imagine, isn’t it? We live in constant struggle with the land. We’ve become as hard and dry. . . .” Father trailed off and sipped his tea. I thought of my favorite place at Bamarren, and almost told Father about it–but how could I describe the enclosure without speaking of her?

“What were they like?” I asked, giving my full attention to him.

“Do you remember, Elim, when I took you to the Hebitian remains outside Lakarian City?”

“Yes.” I was just a boy then, and we had walked around the crumbling walls and piles of stone and pulverized tile. I had enjoyed the trip more for its novelty than for anything else, but I remembered one carving on the side of a wall. It was of a winged creature with a Cardassian face that was turned toward a sun disc. Extending down from the creature’s body were several tentacles that divided just before entering the bodies of people who were standing on a globe and looking up to the creature. The tentacles went through the people and into the globe itself. I told this to Father and he laughed.

“You remember that?”

“And you said that it should be preserved before it eroded.” I remembered his indignation.

“I did. When I went to my superior and suggested that what was left of the entire city be preserved, he told me that it had already been taken care of. What was salvageable was sold to Romulan art dealers, who in turn placed the pieces in various museums and collections throughout the quadrant. All that’s left now is dust.” Father was silent again.

“What were they like?” he muttered, repeating my question. “They valued the soul, Elim. They were organized–they had to be, they had determined enemies–but their energy wasn’t devoted to the conquest of others, to accumulating resources they couldn’t produce themselves. They were able to support themselves, and this self‑sufficiency allowed them to nurture and celebrate their group soul with art and culture.”

“Who were their enemies?” I asked, fascinated and somewhat uneasy with what Father was saying.

“We were.”

The paradox stopped me. “But . . . how is that possible? We . . . we are descended from those people.” I remembered that Calyx had called me an “air man” and wondered if I didn’t get it from Father. Mother often complained that he didn’t have a grasp of what she called our “power‑driven reality,” and he would reply that his reality was driven by the same power that grew his plants and shrubs. These arguments always left the house feeling divided and cold.

“I know this is hard for you to understand, Elim. Our racial policies forbid enjoining with subjected peoples. The Hebitians were the envy of the surrounding planets, what we now call the Cardassian Union. As long as their planet, this one we call Cardassia Prime, was healthy and self‑sufficient, they were able to withstand any attempts at conquest. But when the climate began to change and resources dwindled, the ‘group soul’ weakened. People lost their faith in the old ways . . . disease killed millions . . . it was just a matter of time. The ones who were left surrendered to the invaders, who brought their organization based on military conquest and expansion and blended with them. We come from both these peoples.”

Father fell silent again. A howling child caught our attention. I was grateful for the distraction from Father’s very different version of our past. I’d been taught that the first Hebitians were a primitive people and had died off in the climatic catastrophe; that the survivors had built a new civilization that became superior in all ways.

“I love this place, Elim. And it means a great deal to me that we’re able to spend this time with each other working here.” Father smiled and put his hand on my shoulder. He rarely touched me, and the contact embarrassed me . . . and sent a warm feeling through my body. I felt like one of his plants. He kept his hand on my shoulder and stared at me with an intensity that made me afraid of what he was going to say next.

But he said nothing. We finished work and packed our things in silence. The silence continued throughout the trip home on the public transport. Just before we entered the house, Father stopped and looked at me.

“I want to show you something, Elim.”

He led me into his private chamber, where he kept everything from cuttings to work records. He put his bag down and unlocked a huge compartment. After a moment of moving things I couldn’t see, he pulled out something that looked like a face that was made from stone‑like material. He held it out to me. It was the same creature’s face as on the carved mural I had remembered earlier.

“What is it?” I asked.

“It’s a recitation mask. Hebitian poets wore it at festivals that celebrated Oralius.”

“Was he . . . their leader?” I asked.

“In a spiritual sense.”

My confusion must have been apparent, because Father nodded his understanding. “I know this is difficult. Oralius was not a corporeal being, Elim, he didn’t live as we do. He was a presence, a spiritual entity that guided people toward the higher ideals they were encouraged to live by.” Father was working hard to describe something for which I had absolutely no reference point.

“How did this ‘encourage’ them?” I asked.

“At the festival, the poet would put the mask on before he’d recite. In this way, he was no longer Elim or Tolan or any of ‘us.’ He was a conduit . . . a connector who with the help of his poetry brought the higher power of Oralius down to those of us who were there . . . who wanted this . . .” Father searched for the word.

“Encouragement? “I ventured.

“Yes.” Father was pleased with my interest.

“Was this your . . . ‘power,’ which makes the plants and flowers grow?”

Father’s face broke into a beaming smile, and I thought he was going to grab me. He had never looked at me like this, and I felt somehow proud that my question had gotten such a reaction. Suddenly he looked past me, and his expression–so open and so animated with the attempt to explain what essentially was unexplainable–became as unreadable as that disembodied mask.

Mother was at the door. I don’t know how long she had been there, but she was not pleased.

“Oh, Tolan,” was all she said.

“Get cleaned up, Elim,” Father said. I was aware of a strong forcefield that I had been caught in the middle of many times before. It always made me feel helpless, and this time was no exception. I gladly complied. As I was about to leave the room, however, I saw Mother’s eyes as she looked at Father. Intimate was not a word I would ever have used to describe their relationship–efficient or collaborative, perhaps–but I had never seen how much distance actually existed between them until this very moment.

I hurried past Mother and out of the room.

3

Entry:

“Is it too hot for you?” I asked.

“It’s hot.” Remara tentatively arranged her long body along the surface of the smooth rock. “But I think it’s bearable.”

Remara had asked several times if she could join me in the holosuite program I frequented, but I had never taken her seriously. I was convinced that only Cardassians could bear the heat of the rocks. Finally I agreed, but I was prepared to end the program immediately, anticipating that she’d change her mind after the first blast. But somehow she not only survived it but managed to find a position on her rock that looked almost comfortable. I must confess that her lithe body pressed against the rock presented a vision of feminine sensuality that added to my enjoyment.

“You used to come here with Ziyal, didn’t you?”

“We both enjoyed the experience. It was like a haven from the storm.”

“Yes, it must have been difficult.” Remara shifted her body, and I could see that she was perspiring profusely. Her skin began to meld with the rock.

“What was difficult?” I asked.

“Your relationship with her father. It must have affected you and Ziyal,” she replied.

“She knew who he was,” I said.

“Did she know who you were?”

“Of course,” I smiled. “A plain and simple tailor who craved a friend to sit with on the rocks.” Remara smiled back, but she was not to be deterred.

“Did Ziyal know that you had played a part in the death of her grandfather?” Her smile was even more radiant because of the effects of the heat. The longer she endured, the more beautiful she became.

“I’m glad to see the heat agrees with you, my dear. I had no idea that Bajorans had this kind of tolerance.”

“We’re very fond of our solar baths,” she said, shifting again to another graceful position. “Did she hold his death against you?”

“If she did, she never shared it with me.”

“Weren’t you at all curious to know?”

“Not nearly as curious as you are about me. When Colonel Kira asked me why you were making inquiries, I joked that perhaps you were writing a book. Perhaps it’s not a joke. You’re very well informed.”

“Nerys asked you that, did she?”

“And she found it curious that you wouldn’t address these questions to me directly.”

“I’m not surprised.” Now she was fully reclined on the rock with her face up. It was getting difficult to breathe. How ironic if I were the one to call off the program because of the heat. “Nerys and I have had our difficulties in the past,” she said, her voice seeming to come from a great distance. Her eyes were closed, and she was totally integrated with the rock

“Oh?”

“We knew each other on Bajor.”

“Really? Were you in the Resistance as well?” I watched her raise her right leg and flex her foot, which made the lean muscles along her thigh ripple. I forced myself to breathe deeply. Perhaps it was the heat, but even with the distance between us her physical presence was crowding and overpowering me.

At one point Kira and I became quite close,” she said dreamily. I wondered if she were about to fall asleep.

“And now you’re not.”

“Our lives took very different paths. No,” she finally answered, “I didn’t join the Resistance.” Remara opened her eyes, sat up, and gave one last serious stretch. “You know, Elim, I think I’ve reached the limit of my tolerance.”

And not a moment too soon, I thought. In one easy motion, she slid off the rock and led the way to the exit. I lingered for a moment, to savor her movement and wondered how an artist could capture the exquisite harmony of her physique. I also wondered how a man could continue his relationship with her knowing full well the danger involved. The major’s question echoed in my head: What doesshe want from you, Elim?

4

Entry:

The next morning I was surprised to find that Father had left for work without me.

“You’re coming with me this morning,” were Mother’s first words. When I began to ask where we were going she cut me off.

“You’ll find out,” was all she would say. I quickly ate something while she waited. Neither of us spoke; the heaviness in the room said everything.