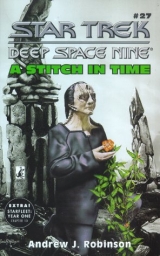

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

I looked for my advantage. This was not an equal match, and my gigantic friend was in the full flush of a berserker blood lust. I sighed. I’m too old for this, I thought. I needed to slow him down and find better ground than this. As his head appeared coming up the narrow circular stairwell I charged, grabbed hold of the stanchion, swung my body around, and kicked the side of his head with both feet. This just made him angrier. I made for the upper Promenade–and wondered if Calyx might be enjoying this spectacle from wherever he was. The giant’s roar caught the attention of the people on the upper Promenade, one of whom was Chief O’Brien, who emerged from an alcove where he had been doing some repair work on a panel.

“Garak, what have you got yourself into now?” he asked as I approached.

“Get security, Chief, and tell them to prepare the biggest cell they have . . . or a smaller coffin for me,” I said as I moved into the alcove and squeezed through the opening where the panel had been. I had an idea. I could hear the Chief behind me try to reason with the berserker, who just pushed him aside.

I came out into a Jeffries tube. I wasn’t sure which direction to take, but I had to choose quickly. My pursuer was struggling with the small passage, but he was not going to be deterred.

“Go left, Garak,” the Chief kindly directed, “and take the third opening on your right!” I think he understood my plan. The massive Klingon followed me as I crouch‑ran up the tube. One, two, three openings. Could I fit in? No time to debate. I squeezed in on my belly and shimmied forward. The giant grabbed hold of my left foot and started pulling me back. I strained against his vise‑like grip . . . and my boot came off in his hand. I managed to shimmy beyond his reach and thankfully out the other end and into a larger parallel Jeffries tube.

I turned back to see if the Klingon was foolish enough to follow. It was such an obvious trap. His anguished roar answered me. Somehow he had managed to squeeze himself far enough into the passage to get thoroughly stuck. He couldn’t go forward or back. And I recognized the look on his face. He was suffering from a claustrophobic attack. The more he struggled, the worse it got.

“Don’t move, it’ll only get worse,” I warned him. His look was a mixture of wanting to kill me and desperately needing my help.

“Don’t move!” He calmed down. “Keep breathing, deeply. Deeply. That’s right.”

“Help me,” he croaked. I was touched by the giant’s childlike surrender. I knew the feeling well.

“I will,” I replied and immediately wondered why I had agreed. I’m getting soft, I thought. However, I needed to find someone who could help me help him.

“Don’t leave me!” His voice was on the edge of panic. The tables had indeed turned.

“I won’t. But you must promise me that you’ll behave once you’re extricated.” His eyes flashed with impotent anger. I decided that I might as well get something for my trouble. “I’m not going to help you unless you promise me that you’ll behave like a gentleman.”

“I promise.” Claustrophobic anguish won out over Klingon pride.

“And you must promise me one more thing.” I wasn’t finished.

“What?”

“That you’ll never call me or any member of my race a spoonhead again.”

“But you area spoonhead,” he reasoned. The request was incomprehensible to him.

“I’m warning you, unless you make a solemn warrior’s promise, I will desert you.”

“I promise.” The poor creature was nearly in tears. I almost felt sorry for him.

The day after the incident, Odo called me in to take my statement. As I approached his office, the giant, accompanied by two security people, was coming out. He stopped when he saw me, and I braced myself for trouble, as did the two guards. Instead, he solemnly thanked me for staying with him until O’Brien and Odo arrived.

“I wouldn’t have expected that from a . . . Cardassian–you see, I haven’t forgotten my promise,” he assured me. They moved off, and I must admit that I was quite taken aback. Evidently there is honor among dolts.

Odo was his usual thorough self. After my version of the incident, he reckoned that since the damage was minimal and the Klingon was returning to the front the case could be closed.

“What about the dabo girl?” I inquired.

“She’s not pressing charges.”

“How magnanimous of her.”

“Magnanimity has nothing to do with it. Quark won’t let her,” Odo said with disgust.

“Ah–let me guess: Bad for business.”

“Yes. But she seems quite interested in seeing you to express her gratitude,” Odo said with no irony.

“Well, that’s not necessary.”

“As you wish. Her name is Tir Remara.” The name rang a bell.

I was about to leave when Odo asked about the designs for his “new” sartorial look. I could see that he was masking his concern, so I assured him that the sketches were some of my finest creations, and would be ready within the week. He grunted his thanks and I stepped out onto the Promenade. Love does make fools of us all.

15

Entry:

The days of preparation for the Competition were exhilarating. They started when Nine approached me as I sat alone in our quarters reading the first part of Cylon Pareg’s Eternal Stranger,a saga spanning several generations of a Cardassian family during the early and middle Union. Spellbound by its magic, I tried to avoid the interruption until I saw the expression of demented awe on Nine’s face as he stood waiting. I then understood why he was there.

“Charaban One says that the first meeting . . .”

“Should you be telling me this here, Nine?” I interrupted. Perhaps he could carry a message, but he didn’t know how to deliver it. At that moment Eight appeared and paused in the doorway to register Nine and me before going to his area. Nine was nonplussed; he didn’t know what to do. I put my padd back in my compartment, stroked Mila–who was visible only to me–and quickly walked out. After a confused moment, Nine followed.

When he caught up with me in the corridor he tried to continue with the message, but I motioned him to be silent. His almost total lack of awareness astounded me; he must indeed come from an important family to have lasted this long at Bamarren. The subtleties of security training were evidently eluding him. We were well into the common ground triangulated by the three First Level buildings when I stopped and faced him.

“Was this necessary?” Nine asked. Judging from his offended air, any kind of security was beneath him.

“What’s your message, Nine?” I smiled at him. I wanted to slap his pinched, inbred face, but I doubt that would have furthered my cause. He liked me even less, especially in the present situation.

“Charaban One. . . .” It stuck in his throat. Why was I, a low‑born Ten with no connections, on the receiving end of this message? I waited and continued to smile.

“Yes, Nine?” He grimaced as if he swallowed something bitter.

“The first meeting is tonight, after your tutorial. You’re to report to the Palaestra for cleanup duty. The assignment has been filed with One Tarnal, who will meet you there.” Nine was now back to his officious self. “This is extremely confidential, Ten!” he ended with a final attempt to maintain his superiority.

“I assume Eight is excepted,” I replied.

“What?” He had no idea what I meant. Eight had walked into our quarters and seen the two of us, and was at this very moment putting together a scenario that would be very close to the truth.

“Of course not! No one must know. The fate of Bamarren depends on these plans,” he intoned. A young man whose received wisdom consists of the scraps others have thrown away.

“Thank you, Nine,” I replied graciously. I know he wanted desperately to ask me why I was being involved in his cousin’s mission. He certainly didn’t dare ask Charaban. And it was beneath his dignity to ask me. He swallowed again, an even more bitter taste, and marched off to a life of diminishing returns. It was just as well Eight was alerted. One of my goals was to get him involved before he was recruited by Ramaklan.

When I arrived at the Palaestra after a computer‑systems tutorial at which I was severely criticized for my wandering attention, Second and Third Level agonistics–the advanced training phase after the Pit–were just finishing. One Tarnal met me in the main atrium and led me to the custodial office, where I was given implements and instructed to work until I had cleaned the twelve studios and two hygiene chambers in the building.

“Another murk was supposed to assist you, but he’s been reassigned, and nobody’s taken his place. Don’t dawdle or sleep, and be out of here by the morning classes. Now get going!” As I walked away I heard the custodian ask Tarnal what it was I had done to deserve this punishment.

“Nobody told me. But I know he’s got a mouth on him,” Tarnal replied.

I was well into my fifth room, and convinced that Charaban had set me up and that I wasbeing punished, when a person I didn’t know suddenly appeared in the doorway. He looked around to make sure I was alone.

“Follow me,” he said, satisfied that I was. His body had a low and powerful center of gravity, and his eyes sliced into me when they made contact. There was no denying him. I dropped what I was doing and obeyed. Without a word, he led me down three subterranean levels and into a conference room that featured a large monitor at one end. Charaban and an immensely overweight student were waiting. The latter’s formlessness was a contrast to the compactness of my guide.

“Is this the murk?” the heavy one asked.

“You don’t recognize him, do you?” Charaban replied with his smile.

“He’s filthy,” the heavy one observed with a contemptuous look.

“I’ve been cleaning half the night!” I was indignant. The work was bad enough without the insult.

“I didn’t ask for your opinion, murk!” the fat student snapped. The sharp‑eyed one just studied me, which added to my disorientation.

“A murk who got by you twice,” Charaban needled. He was enjoying himself at the fat one’s expense and I was the instrument. “I don’t think that ever happened to you before.” Charaban turned to me. “He still doesn’t believe it happened.”

The other snorted in disgust, and his jowls shuddered in agreement. I wondered how someone that heavy could endure the physical regimen at Bamarren. He truly was the exception to the reigning student ideal of lean and muscular.

“We’d better get started,” Sharp Eyes quietly suggested.

“This is Ten Lubak,” Charaban abruptly announced to the others. “Ten, this is One Drabar,” indicating Sharp Eyes, “and this is Two Charaban, who was eager to finally meet you.” Two snorted and shuddered again. One Drabar moved to a control panel and entered a code. An image appeared on the monitor that was part topographical map and part diagram.

“There are spies operating everywhere, and we know who most of them are. The best ones we don’t know, of course.” Charaban was not smiling when he looked at me. “You’ll be approached by Ramaklan if you haven’t been already.” He paused and the three of them looked at me. I now understood One Drabar’s function.

“No. No one but One Charaban has talked to me about the Competition,” I directly addressed Drabar. He held my look with his probing eyes and then turned back to Charaban, who computed his look before he continued.

“Ramaklan will. Expect it, Ten,” Charaban ordered. It was impressive how he could move with warp speed between smiling charm and steely command. I nodded in response. He referred to the monitor.

“The rock formation at the center is the one Gramarg successfully defended two Competitions ago. Tarnal couldn’t touch them. It doesn’t look like much of a challenge . . . until you actually get out there. The exposure, the slope of the terrain . . . it all works for the defender. Considering the stakes of this Competition, Ramaklan is well advised to defend here.” He pointed to the redoubt an obvious stronghold for the defenders. “It’s a real challenge.” Charaban fell silent, and the four of us studied the graphic.

This was a part of the Wilderness I was not familiar with. Charaban was right; at first sight it didn’t look formidable. But as the coordinates revolved dimensionally and we perceived the gradual and insidious angle of the rising slope that led to the formation, we understood that the shape of the high ground allowed for no blind spots. There were 360 degrees of unobstructed exposure for the defenders.

“Any ideas? Observations?” Charaban asked.

“Ramaklan bastards!” Two Charaban muttered. “Look at that!” His stubby finger traced a circle in the air. “They can see everything around them. They won’t need that many men scanning terrain from inside. So of course they’ll commit the better part of their troops to the flanks coming out of either side of the rock formation to intercept any attempts to get behind them.”

“Which can work to our advantage,” Drabar said.

“How?” Charaban asked.

“If a small force canget behind their position, they’ll encounter less resistance in a surprise attack,” Drabar replied, never taking his eyes off the diagram.

“But how do we get behind their position?” Charaban asked.

“Outflank them. It’s the only way,” Two Charaban maintained.

“Both sides?” Charaban pressed. His fat second paused, not sure.

“Yes,” he finally replied.

“Then what’s left for the main frontal attack if we commit enough troops for both sides?” Charaban didn’t wait for an answer. “No, Drabar’s right. It has to be a small flanking force that surprises from behind and executes a holding action while the main force engages frontally.” Charaban was sure of that much. “How do we get behind, Drabar?” He wanted an answer.

“I don’t know yet,” Drabar replied.

“Ten?” Charaban’s eyes were almost angry, as if to ask what I was doing in the same room with them. All charm and politesse were gone. I was startled; it was the same look he’d given me at the Central Gate when I airily announced my success.

“There’s something I don’t understand,” I began carefully. “Why can’t a small force position itself behind the enemy beforethey array their flanking positions?”

“Because, murk, they are allowed to establish their position before we can begin our attack!” Two Charaban threw an exasperated look to his superior.

“They can dig in, Ten,” Drabar explained, “and then we have from dusk to dusk of the following day to dislodge their position . . .”

“. . . and take their place!” Charaban punctuated.

“Why are we dancing around, One?” his second wanted to know. “You invited the murk for a reason, and it wasn’t to ask stupid questions.” They all looked at me: Two Charaban with an impatient sneer, Drabar like I was another graphic on the monitor, and One with a questioning smile that wondered if I knew that this was the right moment to grab my opportunity. The image of Palandine stroking her ridges appeared.

“I’m here because I know how to get past their flanks and behind the rock formation,” I said with a confidence that was part bravado.

“Really? Well, mates, I’m glad to have been present for the second coming of Gul Minok,” the fat Charaban bellowed with utter contempt. Gul Minok was a legendary hero of the early Union. I bit down and held my ground.

“Do we know the status of the moons that night?” I asked.

“What do you think, Ten?” Charaban returned the question, not unkindly.

“If it was their choice of time as well as place, all three will be at full strength,” I answered. He nodded in agreement. I was now on surer footing.

“But it’s not that important,” Drabar interjected. “In a Competition all the night probes are coming from one source–the defended area–and they’re trained on the expected direction of the attack. Night is not the advantage one would expect.”

“But still enough of an advantage for the major part of an attack to take place,” Two stated.

“And the advantage grows proportionally to the skill level of the flanking force in operating with stealth,” Charaban added, looking at me.

I knew what he wanted. It didn’t take genius for someone to figure out that my success in the Wilderness depended on my ability to diminish my presence. But to give him what he wanted meant that I would have to teach others the skill. What would I be left with? Would I not surrender the source of my power? And what would I receive in return? The image of Palandine helped me to remember what I had learned that night: that I was being offered the opportunity of a greater power. Charaban watched me. I was at the edge of my experience, and the only way I was going to expand the frontier was to act.

“The difficulty is finding students who can execute the necessary maneuver,” I said, answering Charaban’s look.

“What?” This was too much of a leap in logic for fat Charaban. “What maneuver?” Drabar didn’t understand either, but that only increased his attention.

“Stealth,Two Charaban. Did you leave the room or is it getting too late for you?” Charaban was sharp with his second. He turned back to me. “It’s even more difficult than that. Whoever you use can only come from your group. And as you decide how many you will need, remember that once inside the rock formation you will have to throw up an effective resistance to create the diversion we need.” Charaban was pushing me now.

“With phasers we should be . . .”

“No phasers inside the rocks,” Charaban interrupted. “Only outside. Once you get in it’s hand‑to‑hand combat.” Charaban pushed me even harder. “What’s your plan, Ten?”

“Six men. Two groups of three.” I was sweating with the effort to visualize the operation as I studied the diagram.

“Yes?” Charaban urged.

“I lead one group along the southern flank, which is the more difficult one. One Lubak will lead the . . .”

“No,” corrected Charaban. “You can’t use One.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because he will resent your leadership. He already regards you as a threat. One must never know what you’re doing.”

“That means I can’t use any of his allies.” I was worried as to how I was going to assemble a team with what was left of the group.

“Unless they find greater opportunity with you.” Two Charaban’s tone was almost civil.

Opportunity. Of course. Ambition. The power is with the leader others are willing to follow because he promises them an advantage they lack. I began to see what the exchange was.

“Who leads the other team?” Charaban wasn’t finished.

“Eight.” Logically the best choice, once I got beyond my obligation to One Lubak.

“And if he’s the Pit warrior you claim he is then he should work with the others.” Charaban remembered my assessment and challenged its truth.

“It’s crucial that the members of your group perform well in the combat phase,” added Drabar.

Besides Eight and myself there was Five . . . and Three. I detested Three. Plus he was an ally of One. But his massive strength was matched by his ferocity. Charaban knew that I was struggling with choice.

“Whoever they are, Ten, just make sure that Ramaklan hasn’t already recruited them. Our task is difficult enough; betrayal would make it nearly impossible,” he warned.

“And betrayal means that the leader has failed to earn the trust of his men,” fat Charaban added to the warning.

When I had finished cleaning the last room and replaced the implements, the first colors of dawn were stretching across the desert and lighting my way back to the First Level compound. I was exhausted from the long night’s test. I had made my first alliance, and was now part of a cohort looking to seize political power by an act of force. I felt stripped and exposed. The boy who had played among the stately monuments in the Tarlak Sector and pretended to heroism and great deeds had been left behind. Now that I was faced with the hard work of actual leadership, the fear of failure–the very thing Charaban told me there was no room for–had assumed new dimensions. Find your allies, I heard Calyx say, and work from there.

That morning Eight and I were assigned to a construction unit repairing an old barrier on the western perimeter. I told him I needed to talk without other ears, and we managed to work ourselves away from the rest of the team. He knew about the Competition, and he knew that the Ramaklan and the Charaban were recruiting. It happened that he had an appointment to meet with a Ramaklan recruiter that evening.

“But I knew I’d be contacted by you,” he said as a simple matter of fact.

“How?” I asked.

“Charaban warned me.” Eight studied my confused reaction. “He didn’t tell you we spoke?”

“No.” Anger replaced confusion, but we had to continue our work of identifying weak sections of wall and marking them for repair. And I had to continue assembling my team. “What did he say?”

“He asked me to be involved. When he told me you were committed I agreed.” Again, simply stated. We scraped the wall to cover our conversation.

“Thank you,” I said with relief. Eight was the difference between success and the abyss; especially with the others. Eight was respected by everyone, even Three. One despised him, but he harmed Eight at the expense of his own leadership stature.

“He said you were leading our team, and that you would make the assignments. That’s quite an honor.” In his quiet way Eight was impressed.

I described our mission and what I wanted from him. He would take Five and Three to penetrate the northern flank while I led Two and Four on the southern. I explained my choices, based on the restrictions Charaban had given me.

“Don’t take Two,” Eight said.

“Why?” I asked.

“He can’t be trusted–especially if One is not involved. They’re family.” How did everybody except me have this personal information? “If Two agrees, chances are he’s a Ramaklan spy.”

“Who’s left?” I was certain there was no one.

“Seven,” he replied.

“He’s too raw. His ridges have barely emerged. We need fighters,” I protested.

“He has great heart, and he’s loyal. I’ll make sure he’s ready to fight,” Eight assured me. “I’ll take him on my team and you take Three. That’ll be the challenge. If you can get Three past their flank undetected. . . .”

The signal to stop working interrupted Eight, but I knew what he meant. Stealth requires the kind of sustained patience that’s almost totally missing in Three. If there’s no room for failure, then there must be a solution to every problem. I wanted very much to believe that that indeed was so.

16

Entry:

During the period leading to the Competition, my only respite from the preparations was when Palandine and I managed to spend some time together. Besides the training area, we would meet in the secluded study nooks of the Archival Center and in sections of the Grounds she knew would be safe. Tonight we were in an enclosure of the Grounds that was made impenetrable by the thick surrounding foliage. This was the place she had wanted to show me before we were interrupted by the intern at the Center.

Our conversations covered all the areas that were forbidden–names, personalities, family backgrounds, and most important, the true power structure of Bamarren. The Institute was a microcosm of Cardassian society, and the adults–prefects, docents, and custodians–controlled from a distance. The idea was that students would become more effective citizens of the greater culture if they learned how to administer the microcosm themselves. There was a constant striving upwards at Bamarren, just as there was in the greater society, and at the highest levels that striving was transmuted into imperial expansion. The students of Bamarren were the future guardians of Cardassian security; we would become the eyes and ears of the military, the diplomats and the politicians. In these meetings Palandine was teaching me how to use my eyes and ears in a manner that complemented the teachings of Calyx and Mila.

“And you have to use that wonderful smile of yours more often, Elim.”

“What’s that got to do with listening?” That was the subject, and Palandine had typically made a jump in logic I couldn’t follow. She also forgot that I was a Cardassian male and smiling was not one of our strong features.

“If they feel comfortable with you, people will tell you stories about themselves that will reveal their deepest secrets.”

“But what if the stories aren’t true?” I challenged. “I could smile till my cheeks hurt, and you could tell me any kind of story you wanted–and what would I know about you except what you invented?”

“You would know, if you were truly listening, the kind of story I use to define myself,” she asserted.

“But it’s not the truth!” I maintained.

“Why not? Because it’s not what youbelieve? Or it doesn’t fit a definition of the truth that someone taught you? Look at people, Elim.” Palandine gestured as if the enclosure were filled with people. “Observe them. The way they walk and talk, the way they hold themselves and eat their meals. That’s what they believe about themselves. Is it the ‘truth’? Are they really that way? I don’t know. Perhaps it isa lie. But what people lie about the most are themselves, and these lies become the stories they believe and want to tell you.”

“As long as I’m smiling,” I mumbled. This conversation had started when I complained that others–especially Palandine–seemed to have information that was inaccessible to me. It progressed into one of our heated discussions relating intelligence gathering to the nature of truth itself.

“Truth, as we’ve learned to define it, is not only overrated,” she went on with a controlled passion, “it’s designed to keep people in the dark.”

This last statement stopped me.

“You mean the way we’ve been taught?” I asked.

“Of course.”

“What about our government?”

“They tell us the stories that we need to know in order to be good citizens,” she replied carefully.

“They don’t tell us the truth, is what you’re saying,” I concluded.

“There you go again. They tell us theirtruth, Elim, and we are here to learn how to listen.” Palandine paused and gave me one of her looks that went to the back of my head and made me shiver. “You’re so serious, Elim, so glum that even before you open your mouth you’re telling a story. But the nonverbal stories are the most dangerous, because they can be interpreted any number of ways. You have to smile, because you have power. If you listen to people with the look you have on your face right now, they’ll suspect that you’ll disapprove or criticize or–even worse–laugh at their stories. And there’s nothing worse than being ridiculed. You know that.”

And I did. Perhaps that was why I was so resistant to the idea of smiling. It made me feel vulnerable to others, the way I had with Charaban that night at the Central Gate.

“Let the ones without power scowl and make fierce faces. You smile. It’s an invitation to connect with another person. And once the invitation is accepted, relax and listen . . . you’ll come to know as much as you’ll ever need to about that person,” she said with a smile that I greedily accepted.

* * *

Palandine also introduced me to poetry, particularly the work of Maran Bry, who was notorious for being critical of the Bajoran occupation.

Ghosted light, colored by the gas and

dust of the Corillion Nebula

Dances in my dreams and descends

like a shimmering wave

Where it fills the space between sleep and waking

And clothes my loneliness with your naked birth.

She opened her eyes and the light from the Blind Moon, the third and weakest in our system, reflected the excitement she felt in his poetry. At that moment I could have died and gone to the Hall of Memories if I’d been able to take this moment with me.

“Yes, ‘Solar Winds,’ ” a voice said behind me, so soft as to be almost unrecognizable. “I also enjoy his ‘Paean to Kunderah.’

The price they paid in blood is returned

by your healing kiss,

My matriarch, keeper of the mysteries and companion

To those heroes who stood between us

and eternal night.

It was Charaban; and as stunning as his sudden presence was the choice of poem. “Kunderah” unfavorably contrasts the celebrated victory against the Klingons with the Bajoran Occupation. He stood there, watching us with a bemused expression, framed by the narrow opening of fendle leaves that connected the pathway to our green and muffled enclosure. With his easy grace and smile, it was as if he’d always been here.

“I didn’t know you liked Maran Bry, Barkan.” Palandine behaved as if she expected him.

“You never asked . . . Palandine,” he replied, amused by this use of their names. “And what kind of example are we setting for Elim Garak?” This was the first time I had heard my full name since I had left home, and it suddenly made me feel self‑conscious. I stood up awkwardly.

“No, no, please,” Charaban motioned me back down. “I didn’t mean to disrupt your . . . poetry reading.

” Palandine’s laugh was more delighted than ever.

“ ‘No, no,’ said the Mogrund, ‘I didn’t mean to take the bad children to the subterranean city,’ ” she said with Mogrund ferocity.

“I hope you’re not comparing me to the Mogrund,” Charaban said with mock outrage.

“Well, I suppose you’re a little better looking than that,” Palandine allowed. (The Mogrund was a spiky lump with several frightening red eyes.)

“Unless there are some wrongs here I need to right.” Charaban imitated the creature’s voice–which was easier for him since his own voice was already halfway there. I knew they were enjoying the banter but I felt caught in the middle, and vulnerable. According to the rules, I was in a place I did not belong, with a female student, indulging in “personal excesses.” But if the two of them were concerned, they certainly didn’t show it.

“I never would have guessed the two of you shared a love of poetry,” Charaban said with genuine surprise.

“Who exposed us?” Palandine asked.

“Drabar. I asked him to do a security check on Ten Lubak. You’re not a Ramaklan spy, are you, One Ketay?” he asked with the same lack of concern. Her answer was another laugh and a provocative look that challenged any and all assumptions he dared make about her. I jumped up.

“I swear,” I began, trying to overcome a very dry mouth. “I’ve told her nothing of our plans, One Charaban, and she has never asked.” It was true; we talked about everything except our work.