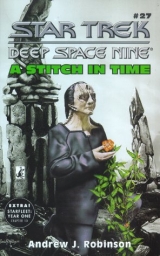

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

19

Entry:

There was an almost surreal quality to Bamarren the next day. The Institute looked like a clean and orderly outpost harboring the sick, wounded, and disfigured from some horrific war. With the help of a cane, I walked with a painful, crouching limp; my right leg and back were just short of being broken. Others were not so fortunate. The infirmaries were overflowing with serious cases like Three, who had lost his eye, and worse. Those races who accuse Cardassians of being nothing better than mindless predators would rest their case if they saw the elite of our youth on the morning after the Competition.

At a special assembly in the outdoor arena, the Bamarren students gathered as Charaban and One Ramaklan stood on the sunken stage waiting for us. I sat with Eight and the other Lubaks, and we dedicated our lives and loyalty to the Empire in a rousing version of “Cardassia Forever.” Unity was the stated theme of the rally, but the actual business was the transference of power from Ramaklan to Charaban, a ritual that was performed by the opposing factions after every Competition to legitimize the new order.

With a brittle dignity, Ramaklan handed the Bamarren Saber, the symbol of student leadership, to One Charaban, who graciously accepted it. In his speech, he praised the Ramaklan side for their “courageous and well‑planned opposition” and we all cheered, knowing that never in the history of the Competition had a side capitulated so quickly. As I watched him speak, I tried to remember that moment the day before when I had clearly seen him assume the mask of leadership. What was it I saw in that moment that continued to nag at me? Could I even trust what I saw, given the state I was in? But his mastery was so complete now, his speech and carriage so elegant and reassuring, that I let the memory of that moment go and joined the others in acceptance and adulation.

I scanned the audience from my vantage point, looking for Palandine. This was one of the few occasions when males and females were brought together. The females had their own Competition and leadership structure, but we all participated in any major group ritual. I finally located her sitting down near the front. She was strongly focused on the ritual transfer and on Charaban. I understood that she’d soon be preparing for her own Competition, and that whatever transpired here today would have special meaning for her.

And then it happened. The irony, of course, was that I had gotten past my mixed feelings of yesterday and was basking in the glow of our victory. I even enjoyed the aches and pain of my body as evidence of my participation. I accepted Charaban’s patronage and leadership, and was prepared to serve as a member of his council. At one of our last planning sessions, Charaban had told me that after we’d won the Competition he was going to ask me to join the council as his Second Level liaison, a prestigious position that would consolidate my own base of power. I was about to become a member of the inner circle of Bamarren leadership.

As Charaban introduced each member of his council, with his title and a brief description of his duties–Two Charaban would coordinate and organize the council agenda, Drabar would oversee all school training programs–I was becoming increasingly intoxicated with a nervous excitement. As a young boy playing in the Tarlak Sector, my dreams and fantasies had been fueled by a desire for this kind of recognition. I grabbed hold of my cane, determined not to stumble as I made my way down to the front.

“. . . and last, for the important position of Second Level liaison, which requires someone who is able to represent his entire Level in such a way as to assure their voice in all policy matters. . . .”

All First and Second Level business would funnel through me before it reached the council. The power of the position was self‑evident. I positioned my good leg, so that I could rise without wobbling. Eight, anticipating that I would be called, was ready to assist if necessary.

“. . . Nine Lubak!”

I started to rise, expecting a correction. I had heard the words, but my body was programmed to go. Eight, however, grabbed my elbow and prevented me from making an even bigger fool of myself. Nine Lubak? But there was no correction. Nine, sitting almost directly in front of me, rose to the cheers and applause that rightfully belonged to me. Nine Lubak!? I had a violent urge to vomit. Eight turned to me. I thought he was going to instruct me to breathe again, but he knew better. I retreated inside and put on a neutral mask. At the end of the ceremony we rose and chanted the Ten Obligations and ended with–

“Victory!”

“For the Empire!”

–three times. Eight, I knew, wanted to speak, but I remained behind the mask and hobbled off. I didn’t want to speak to anyone . . . and I didn’t, for days following the ceremony. I simply disappeared.

20

Entry:

The truth is that I have come to enjoy tailoring. The problems of measuring, choosing a fabric and design suitable to the person and the occasion, cutting and putting the pieces together in a comfortable and attractive fit can keep my mind away from those realities over which I have no control. And the more difficult the problem, the more peace of mind I am able to maintain. Designing something for Odo, for example, is a unique challenge. He appeared in my shop one day and began to inspect the mounted displays as if there were hidden messages in the designs and arrangements. When I asked if there was something I could help him with, he replied that he was looking for some “ideas.”

“Changing style, are we?” Odo shrugged, trying to appear unattached to such frivolous concerns. But I knew what this was all about–it was only a matter of time before he decided to make himself more attractive to Kira. Yet as I tried to elicit the specific details of what he wanted, he became shy and reticent–almost irritable.

“Something that’s not so . . . baggy,” he said as he impatiently gestured to his drab constable uniform. I could understand his concern. Major Kira’s tightly wrapped figure made us all look baggy.

I looked up from Odo’s designs, stretched, and felt a twinge of stiffness in my lower back. I had lost track of time, and decided that a short walk would relieve the tension that had accumulated from holding the same physical position for so long. As I came through the doors I nearly ran into Dr. Bashir.

“Doctor. What an unexpected surprise.” And it was . . . for both of us.

“Hallo . . . Garak. . . .” I realized that his breeziness was a cover for the awkwardness of this chance encounter. Was he passing by? Coming in? Standing here debating with himself?

“Can I offer you some tea?” I asked, perversely ignoring his discomfort.

“I don’t want to be a bother. I’m sure you’re busy,” he gently demurred.

“No bother. Your timing’s impeccable, as always. I was just taking a break. It’s that time of day, isn’t it?”

Bashir smiled and accepted the invitation. I led the way back into the shop, and while I coaxed two teas–one red leaf and one Earl Grey–from my ancient replicator in the back, the doctor strolled about as if he were genuinely interested in the various sartorial displays. He was clearly ill at ease, and I wondered how the gulf between us had widened to such an extent. I was determined to narrow it.

“Who was this Earl Grey person?” I asked, as I cleared a space for us at the counter and positioned two stools.

“I don’t really know. Probably a rich man in our nineteenth century who came up with this blend,” he speculated.

“More money than taste,” I replied. The smell of the tea always put my teeth on edge.

Even with his discomfort, Bashir’s laugh had an ease and charm that reminded me of someone else. We remained silent as we sipped our respective teas. Sounds from the Promenade drifted in.

“I understand that you were quite the knight in shining armor the other day,” he said, breaking the silence, obviously referring to my escapade with the Klingon giant.

“Please, Doctor, it’s an incident best forgotten by everyone,” I replied.

“Why? You behaved honorably not only toward the dabo girl, but with the Klingon soldier as well. Staying with him like that when he was suffering was well beyond the call of duty,” the Doctor said sincerely. “Are you embarrassed by what you did?”

“I’m embarrassed by the attention it’s brought me. Please, let’s say no more about it,” I requested. The Doctor shook his head and went back to his tea. We drifted into another silence.

“What I amembarrassed about,” I said too loudly, “is my lack of control at our last luncheon. It was inexcusable.”

“It’s one of the reasons I stopped by today. I hadn’t seen you since and I wanted to make sure you were all right,” he said.

“That’s very kind of you, Doctor. I’m fine.” This took me by surprise. Perhaps this was not such a chance encounter after all. He waskind–perhaps the kindest person I’ve ever known. His courtesy, his consideration, indeed, his willingness to put himself at risk for people he didn’t even know often astonished me. But I found his present concern about my welfare grating. I renewed my determination to rise above my irritation.

“You seemed quite upset when you left,” he began, knowing full well how crotchety (as he put it) I could become at these ministrations of his. “Have you been taking those pills?”

“No . . . well, yes, but I don’t think they’re doing much.” After the incident when the Doctor removed the cranial implant and saved my life I had terrible headaches. They have lessened considerably, but during moments of stress my head can sometimes feel like it’s coming apart.

“You should have told me,” the Doctor admonished in that parental tone he took with his disobedient patients. “I’ll reconfigure the formula and have some new pills for you tomorrow.”

“That’s very kind of you, Doctor,” I repeated, attempting to control my growing impatience.

“What is it, Garak? What’s going on?” he asked with the disarming directness of his profession.

“Other than waiting for this invasion to take place? I’ll be an old man when the Federation finally gets organized. Is it really necessary to get everyone’s input? Romulans and Klingons need to be toldwhat to do, not consulted or persuaded!” The expression on Bashir’s face told me that I was working myself up again. “As you can see, my patience is being strained.”

“Are you afraid of what you’ll find there when the invasion happens?” he asked.

“Perhaps of what I won’tfind there,” I replied. He nodded. Silence returned as we sipped our cooling teas. Even if I had wanted, how could I even begin to explain to him?

“Quark has a new, rather interesting holosuite program,” he said, changing the subject–or so I thought.

“Let me guess. It has to do with some epic battle pitting the beleaguered British against some Cardassian‑type implacable foe,” I needled.

“No, no,” Bashir laughed. “I’m afraid now’s not the time for that. Reality has overwhelmed fantasy. No, the new program enables one to revisit his past. To pick a time, a pivotal incident.”

“For what purpose?” If I wasn’t sure, my returning irritation alerted me to where this was going. I knew I had to be careful.

“With a minimum of programming–time, place, key people–you can recreate a scene where you feel something happened that . . .” Bashir paused, looking for the word.

“. . . that was negative, injurious, a wrong choice,” I prompted.

“Yes,” he conceded.

“So you can change it,” I added.

“Well, not actually,of course . . . but psychologically, physiologically. . . .” He also was treading very carefully. I took a deep breath.

“And you think this is something I should do?” I asked bluntly.

“Honestly? Yes, I do,” he replied, relieved that it was finally said.

“I see.” The tea was cold now, but I kept sipping. “But you wouldn’t need a program like that, would you, Doctor?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I have moments in my past. . . .”

“No,” I interrupted. “I mean that with your enhanced genetic capacity you are able to revise your personal history just by sitting in a room and rethinking those ‘moments’ from your past.”

Bashir said nothing. With a faint smile, he looked down into the mug of tea he was holding between his hands, as if trying to keep it warm.

A Bolian client came down the steps outside the door and was about to enter the shop, but for some reason he stopped at the threshold. He looked at us, turned, and went back the way he came.

“I’m keeping you from your business.” Bashir stood up. “I won’t take up any more of your time.”

“I’m pleased you stopped by.” I was about to escort him to the door.

“No, you’re not,” he said quietly.

“Excuse me?”

“Garak, I come from a culture that has perfected the ‘stiff upper lip,’ ” he explained with the same faint smile.

“What does that mean?” It was a genuine question; there was a change in his attitude.

“It means that we never complain, never admit to our feelings, never ask for help. It’s just not done,” Bashir explained. “And those people who ‘lack character’ and insist on airing their needs–especially in public–are subject to ridicule . . . and worse. Does this sound familiar?”

“Perhaps,” I replied softly.

“But I’m also a doctor, Garak. And I know which group of people suffers the most. I really won’t take up any more of your time.” He extended his hand, which he rarely did, and I took it. “Thank you for the tea.” He turned and went out the door.

I stood there for a long moment, deeply upset. I felt trapped within myself, knowing what I had to do to get out but unable even to begin. Yes, Doctor, it does sound familiar. But as to the question of which group suffers the most. . . .

21

Entry:

At the end of three years, a review process was customary, to determine whether or not a student would progress to the next Level and if so, with what designation. It was a nerve‑racking time for all of us. If you didn’t progress, you were sent back home in disgrace. And if you did, you were given your position in the group commensurate with your evaluated performance of the past three years.

After Charaban’s betrayal I became as withdrawn and solitary as I had been when I first came to the Institute. I tried to spend time with Palandine, but it never quite worked out; between her regular duties and the recruitment and planning for the female Competition, she had little time for anything else. But there was something else, a distance that had crept between us that I didn’t understand. I felt ashamed, that somehow I had failed and it was my fault, but I found it difficult to discuss. This was probably the loneliest I had ever been.

On my way to the review hearing I felt conflicted. The lonely, betrayed part of me desperately wanted to go home and happily follow in Father’s work. I hadn’t seen my family in three years. And yet was it possible, after what I’d experienced here at Bamarren–the taste for success and recognition and, yes, power that I’d developed–to spend the rest of my life cleaning up after parades and tending gardens? The childish fantasies had been replaced by real accomplishment and real friendship. No–I wanted to stay.

And the moment that I came to this decision I realized that I wanted to achieve two goals: to beat Charaban in the next Competition and to win Palandine’s love. The conflict dissolved, and I knew why I wanted to be here. All I had to worry about now was my designation. I was certain that I would progress, but to achieve these goals I needed a high place in my group. I began as number Ten because I came from the lower orders of society. To remain at Ten would mean that I had made little or no impression–which I didn’t for a moment believe would happen. It was clear to everyone that family and social standing count at the beginning, but after that advancement was solely dependent upon performance. Even Charaban’s betrayal could be overcome.

By the time I arrived at the Prefecture I was ready for my hearing. I walked into the anteroom, where other students–including my section mates–waited in varying degrees of anxiety. One Lubak was pale; it was almost certain that he would be demoted. Nine wore a sneering smile and looked at me from his superior height. Ever since he was made Second Level liaison he truly believed it was because of merit. He couldn’t even deliver a message. I smiled back. Three had been sent home; his disability made him unfit for further education. Two fidgeted, preparing, I’m sure, a complicated presentation designed to tell the review panel exactly what he thought they’d want to hear. Why he never went to the political Institute I’ll never know. Four was his relaxed self. He had nothing to fear; he would move through Bamarren from beginning to end on a straight line. He always knew how to take care of himself. Five would no doubt move up; he was an asset in every area, and except for Eight the most decent one in the group. Six had long since gone home. He wanted to succeed so badly, but his body couldn’t withstand the constant assault of the training. I’m sure he found an academic situation. Seven was amazingly calm. Ever since the Competition he was a new person. Even his ridges looked stronger. He was sure to advance. Eight was the only person who deserved number One as much as I did–maybe more. My solitary behavior was not always in service to the group. Eight and I exchanged encouraging looks. The support of my one constant friend was all I wanted. I sat there and shut out everything else.

“Ten Lubak!” I jumped up and One Tarnal, our section leader, ushered me into the Lower Prefect’s office. Going in numerical order, I was the last one of my group to go in. I was surprised when Tarnal didn’t come inside with me. And when my eyes had adjusted to the darker room, I was even more surprised to see only two people, the First Prefect and someone in civilian mufti standing with his back turned toward me pouring a drink. Where were the student evaluators? The Lower Prefect? Why would the First Prefect involve himself in a First Level evaluation? And who was . . . ?

“Hello, Elim.” The stranger turned and it was Enabran Tain!

“Ten Lubak.” The Prefect motioned me to the chair, but I couldn’t move. The two men just looked at me. All my preparation for the evaluation flew out of my head, and I felt as exposed as I had my first time in the Wilderness.

“Ten Lubak,” the Prefect repeated.

“Yes, Prefect,” was all I could manage. What was Tain doing here?

“Sit down,” he instructed. I obeyed. Tain passed an information chip to the Prefect, who consulted it. During the ensuing silence I stole a glance to Tain, who was wearing his avuncular smile. What do I call him, I wondered. Certainly not Uncle Enabran.

“What do you think you’ve learned here?” the Prefect finally asked. It wasn’t so much his question as his attitude that threw me off balance. The question I had expected; his air of boredom, as if the day was one student too long, I hadn’t.

“I . . .” He wasn’t even looking at me. Tain, however, continued to smile and wait patiently for my answer. Somehow his presence, disorienting as it was, encouraged me, and I found myself directing my answers to him.

“I’ve learned that appearances deceive and that the purity of my thinking creates a sure path to the truth,” I replied.

“So,” Tain began, “you believe all this to be a lie?” He gestured to the room.

“It’s deceptive.”

“Why?” he asked.

“Because our thinking is impure. . . .” I still didn’t know how to address him.

“Is that all? The purity of one’s thinking?” he pursued.

“There are the hidden intentions of others.”

“How are they hidden?”

“By what they say they are. How they present themselves. But pure thinking is trained to penetrate these guiles and come into direct contact with the true intention.” My confidence was returning, and I was able to maintain a strong contact with Tain. Ordinarily it would be considered extremely disrespectful to look at an elder like this, but behind his genial demeanor was a serious challenge. It was like the game we had played when he’d tested the keenness of my observation on the street.

“How is pure thinking able to penetrate the appearance?” Tain’s smile was now gone. I hesitated.

“How, Elim?” The questions became sharper.

“Initially by watching the direction of the eye movement when the interrogee answers, the frequency or absence of blinking; the intonation of the voice, the inflection–was it flat? Overstated? Were the answers glib, prepared? The breathing. . . .”

“Yes yes,” Tain pushed me beyond the basics. “What else?”

“If the person can’t hold his space.”

“Space? Explain.”

“If the energy field around him loses its shape and dissipates, then he has no defense against my probe and I can penetrate to his essential core.” As I held Tain’s look, I realized that I was locked into hisenergy field. We were two Pit warriors engaged in a strategem.

“Who am I, Elim?”

I didn’t hesitate. “Someone I must never let out of my awareness.” This was the first time I was not terrified by his steady and unblinking eyes, which revealed nothing but my own reflection. After a moment he nodded and broke eye contact.

“And what do you think has been your most serious lapse of discipline, Ten Lubak?” the Prefect asked in his disinterested tone. Or was it rather an uninflected way of asking questions that would reveal nothing. I began to answer that there were certain classes where I had given in to the boredom and did nothing to motivate my interest.

“And what about your regnar,Elim?”

The breath flew out of me. I looked at Tain with naked amazement.

“Mila. Is that his name?”

In an instant, my carefully constructed mask for this meeting was ripped away, and I experienced a fear I had never felt before. I realized then that Tain knew more about me than I had ever imagined. The Prefect now looked at me for the first time.

“Ah, I see,” Tain continued when I couldn’t. “You think that you’re the only one who can ‘disappear.’ A big mistake, Elim.” He watched as I started to breathe again.

“Is there a lesson here, do you think?” he asked gently.

“If you’ve mastered a tool or technique. . . .” I began, but I needed more air, and my tongue was thick and dry. They both waited patiently while I swallowed and breathed. “. . . Then there are others who have done the same before you,” I managed to get out. Calyx first taught me this lesson.

“That’s right, Elim,” he said as if he were addressing a child. “Whatever your mind conceives or imagines already exists in the world. It doesn’t make the thought or conception any less valuable; it just means that this technique you’ve discovered must be used carefully, and with the understanding that if you use it against other people, it can also be used against you.”

With a clarity I’d never had, I heard what he was really saying to me. Charaban had deceived me by masking his true intentions, hiding them behind a friendship he’d never meant to extend beyond the Competition. I had taken it for granted that because he befriended me he had no hidden intentions. I felt a rush of shame. What a fool he had made of me. And then a disturbing thought attacked me: was Palandine doing the same? I knew what Charaban had wanted from me–but what did shewant?

“Then you know about One Charaban and One Ketay.” I looked at them both.

“So you havelearned this lesson. I’m impressed, Elim.” Tain turned to the Prefect. “I think this will suffice.” The Prefect nodded and turned the chip off.

“You will be leaving Bamarren,” the Prefect said to me.

I just stared at him. It was clear that this was the end of the review–and I had expected to receive my new designation.

“Leaving?”

“Today. The shuttle will meet you in front of the Central Gate before the Assembly,” the Prefect explained.

“But . . . this is . . .” It was a stunning blow, but I refused to submit. “This is unfair, Prefect. Yes, I admit . . . I broke rules. But I have done good work . . . in the Pit . . . ask Calyx! In the Wilderness! Charaban’s victory was. . . .”

“He probably would have won, but nowhere near as impressively as he did with your contribution. We know all this, Elim, even with his negative recommendation,” Tain added with his half‑smile. I wasn’t surprised by this last piece of information, but it sharpened the bitter taste in my mouth.

“You’re being assigned to another school,” the Prefect informed me.

“What kind of school?” I asked as my heart sank into the floor.

“You’ll discover that when you get there,” the Prefect answered. “Today you will return home. You will tell your parents only that you are awaiting reassignment. In the meantime, you will work with your father until the orders come. I advise you to make your preparations.”

I automatically stood up, but I couldn’t leave. There was so much that was unsaid, unresolved.

“What is it, Garak?” the Prefect asked, using my name. Just like that . . . I was no longer a student.

“If I had stayed. . . .” I began.

“But you didn’t, Elim,” Tain interrupted. “Pure thinking doesn’t include ‘what might have been if.’ ”

I snapped to, inclined my head and started for the door.

“Mila,” Tain’s voice stopped me. “A woman’s name for a male regnar?”

I just stood there, looking at them both. Did the Prefect know my connection to Tain? Did he know that my parents lived in his house, and that my mother was his servant?

“No matter.” He gave me a last smile, and I left the office. The waiting room was filled again with other nervous students who were studying me intently, trying to discern my fate. I drew myself up and made the choice to expand my presence. I looked them each in the eye. I am number One, no matter what might have been, and from now on I’m going to make my presence count.

22

My shed has become somewhat more bearable, but the clutter and confinement of the interior space requires that I leave the door open. To keep myself busy when I’m not working with the med unit, Doctor, I am engaged in a project I must tell you about. It baffles me. Perhaps you can tell me if I’m losing my mind altogether.

Tain’s house, as I mentioned, is rubble. One day I began moving some of the debris and arranging it into a pile. Since there was too much debris for just one pile I arranged another. And then another. Until after hours of work I had carefully assembled several piles of debris in varying shapes and forms. I continued to create these piles and arrange them for two, maybe three weeks, not knowing what I was trying to accomplish. But the work was satisfying, Doctor–it felt good. And each day, when it became too dark to work, I would survey my creations, and I never felt prouder of anything I had ever done in my life. I don’t know where the shapes came from, and I certainly couldn’t explain their significance; but somehow they held me in their power.

After several weeks I asked Parmak what he thought this was all about. He’d stop by intermittently and check on my progress at various stages, but he always kept his own counsel. On this day, he moved through the piles (there were dozens by now) and studied them from all vantage points. A very careful man. Finally, after what seemed like an age, he stopped in front of the pile that was the largest and held the central, dominant position. He turned to me with the strangest expression on his face–and looked me directly in the eyes for the first time.

“I think this is your own archeological dig, Elim. You are unearthing the artifacts of a previous civilization–a civilization that will never return–and arranging them into a memorial for that civilization and its dead. This is your own personal Tarlak Sector. You’re clearing the way for us to move on. Thank you, Elim. This is an honor for me.”

Parmak then chanted a section of the Cardassian burial ritual. He mentioned the names of several friends and relatives, and as he chanted, the cumulative emotional power of his voice was almost unbearable. I, too, had a list of the dead that long, and whispered their names as he chanted. Parmak then took his right hand, ripped open a finger on a sharp piece of metal, and allowed the blood to drip on this central “monument.”

“Thank you,” he repeated, and walked away, his finger still dripping blood.

But what baffles me, Doctor, is that I attach no meaning to what I’m doing here. I’m just doing it because I need to. And to be truthful, I don’t see this as a memorial at all. On the contrary–if I could, I’d singlehandedly rebuild this city myself, piece by piece. I stood here watching Parmak’s blood dry on this pile of rubble, engulfed by a feeling of loss and utter mystification as to what these piles mean.

Just assure me that I’m not going mad, Doctor.

23

Entry:

I knew where Palandine was in the training area, and I waited behind a barrier for her class to come to an end. She was speaking with a classmate when I made my presence known. Her mate was somewhat shocked that a male student would behave in such a brazen manner, but Palandine gestured that she would deal with me and sent the mate on her way.

“So what did you use me for?” I asked.

“What do we ever use each other for?” she replied without hesitation.

“Answering a question with a question is an old trick, Palandine.”

“No trick. I needed a friend.”

“And you don’t need a friend now.” I hated the tone that was creeping into my voice.

“It’s complicated, Elim.”

I was afraid to ask why.

“What did you use mefor?” she asked.

The question truly baffled me. I only wanted her love. Was that using her? I would gladly have given mine in return. I would give anything . . . and I still would.

“I’m leaving Bamarren,” I said. “Today.”

“Why?” It was her turn to be baffled.

“They didn’t say. I was just told that I was being sent to another school.” As I said it, my heart began to sink again.

“Then you’re not being sent home?” she asked, genuinely not understanding.

“Only until I am reassigned.”

“Reassigned?” She thought for a moment. “Elim, are you sure it’s a school where you’re going?”

“That’s what the First Prefect told me.”

“The First Prefect?” I began to sense her concern.