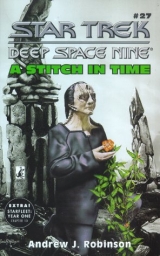

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

The death toll rises every day. We are now over the one billion mark. This is a numbing, dry statistic. I’m certain that when you read this, Doctor, you will have a disturbed reaction. Others will rationalize that the figure is commensurate with Cardassian complicity. And a third group will simply shrug: it’s not their problem. My reaction would probably have been a combination of the latter two. Like most people, I want to get on with the business of my life and what’s done is done and doesn’t warrant any further loss of sleep or appetite.

Our med unit has been converted into a burial unit. It’s a logical progression; the survivors have all been accounted for and only the dead remain unclaimed. More immediate, of course, is the potential for decaying corpses to spread disease. So every day now I am engaged in the hardest work of my life; I find that nothing has prepared me for this. My feelings are spent, my moral rationalizations are empty, and I can’t say it’s not my problem when I’m pulling and lifting and throwing bodies of people who once only wanted to go about the business of their lives.

A Federation official suggested that we simply vaporize all corpses. Underneath the suggestion was the judgment that our burial customs are archaic and morbid. At first I became angry and wanted to berate him for his lack of sensitivity as well as for his own culture’s morbidity in representing death as sanitary and disassociated from life. But I realized that we were no better. We created technologies that dispensed death efficiently and from a distance; we never took responsibility for our personal actions because we were in the service of a greater good–the Cardassian state. Colonel Kira once told me how many Bajorans died during the Cardassian Occupation, and my mind rejected the figure like a piece of garbage. We’d been in the service of the state, I had told myself, and the state had determined what was necessary. But now I understand why she hated me. More important, I now understand that constant burning, almost insane look in her eyes.

Most of us who are left, Doctor, are insane. We have to be in order to survive and emerge from our isolation. It’s the only way we can live with the pain of what we did. Or didn’t. Each of us accepts the amount of responsibility we are capable of bearing. Some accept nothing, and these people are quickly swallowed by their isolation, their insanity transformed into a rationalized evil. A smaller group accepts total responsibility, and their insanity is an unbearable burden that cripples and eventually grinds them down. The rest of us carry what we can and leave the rest. For myself, Doctor, when a corpse is too heavy to bury I try to remember to ask someone to help me.

18

Entry:

“Was he a member?” Palandine asked.

“I don’t know. I’ve often wondered myself. I suspect he probably was. He was a simple man.” The sun was going down and we were completely immersed in the shadows cast by the foliage.

“You make his simplicity sound like a defect,” she observed.

“Tolan was . . . somewhat gullible . . . superstitious. . . .” My feelings about the man had become conflicted, and Palandine picked up on this.

“Was he your real father?” she asked.

“Why do you ask?” Ever since Lokar had reported our encounter on Romulus to Palandine there’d been any number of questions she’d tried not to ask.

“I don’t know. I suppose I’m just trying to reconcile statistical analysis with Romulan gardens.” We lapsed into a long, stony silence. Usually she knew better than to expect a real answer when she did ask about my working life. We both tried not to venture into certain personal spaces; often the attempt functioned as a barrier. I’m sure she knew that I was more than a data analyst at the Hall of Records. She also understood that the less she knew about what I did the more chance our relationship had to survive. For the same reason I never asked about Lokar. The less information, the less damage if either one of us was betrayed.

“What do you hear from Kel?” I asked, trying to find a way around the barrier. She was completing her first Level at the Institute for State Policy.

“She may transfer,” Palandine said.

“Really?” I was surprised. Everything I had heard indicated that she was doing well. “To another discipline?”

“She doesn’t know. She’s not happy with the course orientation. She feels that the political education she’s receiving has been reduced to learning how to serve the military. She feels that it should be the other way around.” I could see that Palandine was concerned.

“A radical idea, but many people feel the same. How does her father feel?” I asked.

“I’m afraid she won’t get much support from that side of the family,” she replied carefully. I wasn’t surprised. Besides knowing the close alliance between the Lokar family and the military, I was also aware of a group called the Brotherhood, which was made up of elite Cardassian families traditionally associated with the aristocracy and the military. The Lokars were a mainstay of the Brotherhood; Barkan’s father, Draban Lokar–a venerable member of the Detapa Council–made little effort to hide his contempt for the civilian‑led government and fully supported the autonomy of the military’s Central Command. The Brotherhood claimed to be a friendly organization engaged in sporting and social events. As it turned out, I was alerted that at any moment I’d be assigned to investigate the Brotherhood and rumors of a conspiracy to disrupt the current tenuous balance between the Civilian Assembly and the Central Command.

“What about your family? Do they have any advice on the matter?” I asked. Palandine laughed.

“My parents are older people, Elim. When I enjoined with Barkan and gave up my career they felt that their work was done. They hold the Lokars in such high esteem that whatever old Draban decides is just fine with them.” The darkness and rising chill weren’t helping the mood. I stood up.

“Kel’s a very resourceful young lady. I’m sure. . . .”

“Have you been to one of their meetings?” Palandine suddenly asked.

“What?” I thought she was referring to the Brotherhood.

“The Oralian Way. Have you been?” Her heaviness was replaced by active curiousity.

“Yes . . . once,” I replied.

“Well? What did you think?” she pursued.

“I . . . it was a mistake. I shouldn’t have been there,” I struggled.

“Why not? Because they’re outlawed?”

“No . . . although . . .”

“What, Elim? Just tell me.” She was growing impatient with me.

“I’m of two minds. I know, that’s just another way of saying that I’m confused. One mind says these people are as deluded as Tolan Garak in thinking the Hebitians were a spiritually advanced civilization. They couldn’t adapt and they died–that’s the lesson, and I think we’ve learned it very well!” Very rarely did my emotions race so beyond my control. I was almost breathless. It was more than just anger at what I believed to be the weakness and delusion of these people. I suddenly wanted to throw a tantrum.

“And the other mind?” she asked quietly. I shook my head.

“I’m sorry,” I managed. I couldn’t even begin to put the other thoughts into words. Palandine smiled.

“Yes. What if they’re right? What if they couldhelp us reclaim something noble in ourselves? Where does that leave us?” We stood looking at each other. The night wind gusted through the foliage and I wondered where I’d be if I didn’t have this woman’s friendship.

“Do you remember where they are?” she asked.

“What? Now?” I began to panic.

“It’s either that or a meeting of the Bajoran Occupation Support Group,” she laughed with a delight I hadn’t heard in a long time.

“It was a while ago, Palandine. I don’t know if they’re in the same place . . . or if they even meet tonight.” Her enthusiasm rendered me as helpless as it did when I first met her.

“We’ll find out, won’t we?” She started to leave. I had no choice but to follow.

“What is this . . . support group?” I asked.

“Abandoned women whose children are either grown or away at school. We’re supposed to support our heroes, but we end up supporting each other.”

“To do what?” I asked naively.

“You don’t want to know, Elim,” she replied. As we left the grounds, I thought I heard a snapping sound. When I looked back all I could see was the shadowy outline of the foliage dancing with the gusting wind against the dying light.

It was no trouble finding the house again, but as we stood on the walkway everything was quiet and dark.

“Is this the entrance?” Palandine asked.

“No, it’s along the side,” I pointed. She moved quickly along the building and stopped in front of the door. As I caught up with her, the door opened and the Guide was standing there as if she’d been expecting us. I couldn’t tell if she remembered me, but she reacted warmly to Palandine’s delighted look.

“Come in, please,” she offered, and without hesitation led the way down the narrow stairs. This time instead of turning left into the main room we passed through a curtained entrance to the right. We then followed her into a dark hallway that opened up into a small room with a few low cushioned chairs and soft indirect lighting. The Guide invited us to sit. Palandine immediately complied, and for a moment my discomfort was so acute I wanted to bolt. Although we were the only people in the room, I was aware of movement all around me. As my eyes adjusted, and I reluctantly and awkwardly settled into the low seat, I saw that the walls were covered with a frieze, and that this was the source of the movement. It began at the bottom of one corner and ran continuously around the room, moving gradually higher until it finished at the top of the same corner. It depicted what looked like the daily activities of another time and culture, performed by half‑naked people who were Cardassian, but leaner and somehow more refined. My discomfort with this unaccustomed low style of sitting and with the Guide’s smiling silence was replaced by fascination with the frieze. As I studied the figures I realized how heavy and restricting my clothes were. How protected we were, I thought. And from what? I tugged at my pants to cross my legs. There was nothing salacious about these people, but they were all attractive. The limbs and torsos of both young and old were exposed as they went about their duties of growing, hunting, gathering, building, communing, raising their families in postures and attitudes that were similar to our own but different enough to be considered archaic. The sequence of these rites and activities began with the miracle of birth and ended with the mystery of death. Palandine and I were spellbound as we followed their sensuous movement along the frieze. It was clear that these people had embraced their lives with vitality and joy.

“Hebitians,” Palandine murmured.

“Celebrating the cycles,” the Guide added.

“I want to get up there and join them,” Palandine said. “But we’re a little late, aren’t we?” Sadness passed like a cloud over her radiant face.

“For them, yes,” the Guide laughed. “But not for us. Look at the way the frieze spirals up as it moves around the room. Because it ends at the top only means that their cycle has ended. What you can’t see is that another cycle begins at a higher spiral appropriate for the next age. Our age.” Palandine and I looked at the place where the visible spiral ended, and we tried to imagine the next.

“You seem less careful this time,” she suddenly said to me. She did remember. Somehow I wasn’t surprised. The threat I had felt years before in this woman’s presence–the fear–had evaporated.

“What’s your name?” Palandine asked.

“Astraea,” she replied.

“Elim says that you’re a guide.”

“Sometimes.”

“My name is Palandine. Can you help me?”

“It would be my pleasure, Palandine.”

“What do I do?” Palandine was unashamedly childlike in her openness.

“Come back. Both of you,” she simply replied. Palandine nodded agreement, and something was sealed between them. Just like that. Now the sadness passed to me. I wanted to cry, and my throat began to constrict.

“It’s all right, Elim. When you can. Everyone moves along the cycle according to his or her fateline.” Astraea looked at each of us. “Both of you have work to finish.” There was a long moment that felt like a lifetime, as we sat in the room, thinking about our work. The frieze now began to move in the upward direction. I was too amazed to ask if this was truly happening. People would disappear at the top while more would enter from below. Certain faces were recognizable, but I didn’t know why. Something was also rising within me, an energy moving up my spine to my head, and I began to feel dizzy. Two of the figures could have been Palandine and me, but I couldn’t be sure. I was almost nauseous with the energy surging within me. The figures completed the cycle and disappeared at the top. The frieze stopped moving.

“Thank you for coming.” The dizziness and nausea passed. My head was lighter, and I felt cleansed. I looked at Palandine, and she now radiated with such light that I turned away, inexplicably embarrassed as if I had seen something I shouldn’t. Astraea led the way back up the stairs and ushered us out.

“Come back,” she said with the same warmth. “You’re always welcome.”

As we took the long walk back to the Coranum Sector, neither of us spoke. When we had left Astraea at the door, Palandine was as serene as I had ever seen her; but when she stopped not far from the Tarlak Grounds and looked at me, her face was troubled. The evening had been like a dream that contained an important message I struggled to remember.

“I care for you, Elim–deeply. But even with her help . . . how can we undo the choices?” Such a simple question, and everything inside me began to shrink. She held her hand up and I attached my palm to hers. We held for a long moment. She nodded and walked off into the night, leaving me undefended against questions I couldn’t answer and feelings I couldn’t control.

“Tonight?!”

Prang looked at me. He immediately knew I was not in full possession of myself. This was not the way an operative embarked upon a vital mission. His face reflected a concern I had never seen before. I summoned every resource within me to gather my scattered emotions. After Palandine had left, I had spent the rest of the night sitting in the Grounds near the children’s area. When Prang informed me that I was leaving for the Morfan Province on Cardassia II on an assignment whose termination was “yet to be determined,” I couldn’t control my reaction.

“You knew this was imminent,” Prang said.

“Yes, of course,” I replied. I took a deep breath, and my disparate parts began to snap back. “I was up most of the night. Perhaps something I ate,” I shrugged.

“You look like you’re not eating anything,” Prang observed. If Tain was the father of the Obsidian Order, Prang was its mother.

“I’m fine, Limor. Please excuse me.” I was now in full possession, and relieved that the demands of work would now push everything else to the side. Prang watched me for another moment to make sure.

“You’re going to the Ba’aten Peninsula in Morfan, where you’ll meet your contact. All the information is on your chip.” The Ba’aten was the last remaining rain forest in the Union, which made it a much‑desired vacation area for Cardassians. How the Peninsula had resisted the great climatic change was still a scientific mystery.

“There is one procedure we need to complete today. Come with me.” Prang led me out of his bare office and took me to the research department, where all the new technologies are developed and tested. Mindur Timot, the cheerful and ancient head of research, was waiting for us. He thumped a raised pallet with one hand while working a computer panel with the other.

“Ah, Elim. We have something special for you today. Lie down here, if you will. Head close to me.” I complied, as Timot now thumped me on the shoulder.

“I’ve just about calibrated the connective adjustment. . . .” Timot mumbled, as he continued to work the panel. His other hand was now probing my skull behind the right ear. The man’s ambidexterity was impressive.

“Yes. That’s your molecular structure. Otherwise the brain would never accept the little coil.” Timot held up a small wire device with four or five coils that began with a tight one and widened out. “And that wouldn’t be very good, would it, Elim?”

“What is it,” I asked.

“Well, I don’t have a name for it yet,” he realized with a laugh. “For the time being we’ll just call it the wire. Simply, I’m going to attach the small coil to the cranial nerve cluster that transmits feelings of pleasure and pain.” He held the wire in front of me and demonstrated. “The wider end will be placed just beneath the cranial subcortex, where the Cardassian brain–in its infinite wisdom–” he laughed again as he pressed the actual point, “decides what to do with this pleasure or pain. With the wire, Elim, your pain, at a certain point, mind you, my boy, we can’t take away allyour pain–that would be monstrous–at a certain point, before that critical moment when the pain would induce you to do or say anything to relieve it, at that point, Elim, the wire is calibrated vibratorily to stimulate enough of an endorphin flow to actually convertthe pain into a pleasurable feeling, which would enable you to endure the most vigorous interrogation and, dare I say, torture.” The old man’s enthusiasm raced like a hound to his triumphant conclusion. I was less enthusiastic, however. I looked at Prang. I knew why I was being fitted with this “wire.”

“It’s because of my threshold rating on the enhancer, isn’t it?” I stated more than asked.

“Eventually every field operative will be fitted with the device,” he replied.

“You mustn’t take this personally, Elim,” Timot cautioned kindly. “Your pain threshold, contrary to certain received wisdom, is something that can neither be considered a sign of character strength or weakness nor ‘improved’ by practice. It’s given to you along with your height, weight, and fateline, my boy. When I tell you that this wire will give you no trouble, as long as you don’t meddle with it, you can believe me. You know that, don’t you, Elim?”

“Yes, I do, Mindur.” The man had never given me anything but superb technology and sound advice. “Please continue,” I submitted.

“Good boy.” Timor thumped my shoulder again.

As I stood on the Promontory, which overlooks the southern end of the Peninsula and the Morfan Sea, I understood that nothing could have prepared me for this sight. Surrounded on three sides by the aquamarine waters, the lushness and green vibrancy of the vegetation formed a dense canopy containing a teeming variety of life underneath. It was fed and nurtured by an abundance of rain that fell nowhere else. Above the canopy, complex patterns traced by innumerable species of avian flight made me dizzy. At one time these forests and the life they sustained had covered much of the surface of our planets. I remembered the Hebitian frieze and its lush background. Of course we were different people: it was a different world. The more the forests receded, it seems, the more we covered ourselves. Their world didn’t need an agent of the Obsidian Order to investigate a group of prominent Cardassians who “happened” to be spending their vacation together. It didn’t have Enabran Tain targeting one of his bitterest enemies, Procal Dukat, a powerful member of the Central Command. And I’m certain it didn’t have fathers who refused to acknowledge their sons. If we lived on the next spiral of the cycle of life, how did we know it wasn’t going downward?

“It’s a beautiful sight, isn’t it?” the familiar voice asked from behind. The stealth as well as the familiarity startled me. I was waiting for my contact, and not to hear him approach was embarrassing. I turned . . . and there he was.

“Pythas Lok.” His slight frame and the shadow of a mocking smile stood surprisingly near.

“But you can’t afford to get too lost in the scenery,” he said. “Otherwise people can creep up on you.”

“Or ghosts from the past.”

“Did you think I was dead, Elim?” he asked.

“I didn’t know what to think. I kept track of you until Orias and then every trace of your existence was erased. It was like you never existed.”

“True, but I was never a ghost.”

“Whenever I made an inquiry it was blocked. And then I heard a rumor that the Order had organized an ‘invisible’ cadre. I couldn’t confirm it, but I always had my suspicions.” Pythas didn’t answer–and I didn’t expect him to. “It’s good to see you, Pythas.”

“It was just a matter of time, Elim. Come inside. I think I have some information that can get us started.” His grace was even more refined as he moved to the small house that was our assigned base of operations. If anything could have taken my mind off downward spirals it was the appearance of Pythas. As I followed his light and soundless tread, I felt invigorated for the task at hand.

* * *

“Draban Lokar?” I repeated.

Pythas nodded. “He and Dukat are the primary motivators of the Brotherhood.”

“Are the sons, Barkan Lokar and Skrain Dukat, also involved with this business?”

Pythas nodded, again. “I’ve had the opportunity to watch them both in action,” he said.

“On Bajor?”

“And on Empok Nor. They’re definitely members of the Brotherhood, but they’re not part of this gathering at the compound,” Pythas assured me. The “compound” was a vacation resort privately owned by the Brotherhood for the benefit of its members.

“Did you also observe Gul Toran on Bajor?” I asked.

Pythas looked at me with a thin smile. “I would have been surprised if you hadn’t heard.”

“And shortly after the Competition Tain recruited you,” I said.

“What was good for you, Elim, was usually agreeable to me as well,” he wryly observed.

“Do you suppose Tain recruited other people who were betrayed by Lokar?” I asked.

Pythas shrugged. “What better way to motivate your agents than to give them the opportunity to settle old scores?”

“All right, my friend, let’s see if we can’t settle some of our own,” I said as I rubbed my hands together.

Pythas had spent enough time in the Peninsula to become habituated to the mysteries of the rain forest. It was an assignment ideally suited to his temperament. Over the years, his modest demeanor and quiet ways had turned him into more of a solitary person than I ever was. I had learned to withdraw my presence as a tool, but I was always aware of my need for contact, and that my value as an operative lay in my ability to engage others in a nonthreatening manner that drew them out. Pythas had learned to withdraw his presence as a way of life–and he moved through the world like a shadow. I was not surprised that Tain had recruited him for the “invisibles.” It took a special person to be able to operate in such unrelentingly anonymous circumstances–no family, no fixed base or identity–and there was no doubt in my mind that he was one of the most brilliant agents in the Order.

Our relationship picked right up where it had left off at Bamarren. Other than Prang, I have never met anyone where so much was communicated with so few words. His eyes had a depth and eloquence that told me everything I wanted to know. How ironic that my lust for conversation was satisfied by someone who rarely spoke. When he was betrayed in his final Competition at Bamarren, he had considered taking his revenge on Four Lubak, but soon came to realize instead that Lubak and Barkan Lokar had done him a favor. Pythas not only admired Lokar’s ability to seduce others to his will, he recognized it as an indispensable trait of leadership that he didn’t possess. He’d been about to resign his One status when Tain entered his life. It was almost uncanny how Tain stayed so thoroughly informed of our Bamarren progress; I’ve often wondered if Calyx had been involved. With the invisibles, Pythas found his life work and seemed genuinely fulfilled. If he missed the intimate connection to a family, he never said.

Our assignment was a simple one: we were to gather indisputable information that we could present to the Detapa Council and the Civilian Assembly to discredit both the Brotherhood and Tain’s enemy, Procal Dukat. To this end, Pythas used the cover of Tonarkin Bine, an experienced forest guide who’d been recommended to the Brotherhood as someone who would be invaluable in planning their recreational activities. Dukat was an avid outdoorsman, and he met with “Tonarkin” several times to arrange ambitious forest treks. Pythas won him over with his unassuming confidence and familiarity with the forest. This was no mean feat, for hidden within the beauty and endless variety of the flora and fauna that attracted people to the rain forest were innumerable dangers that posed serious threats to the uninitiated. It was planned that before the main trek, which would involve several members of the various Brotherhood families vacationing at the compound, Pythas and Dukat would take a shorter trek to explore some possible routes. This suited Dukat, who wanted to have a more authentic wilderness experience before the “women and the complainers” got involved.

After they had settled in at the campsite, located near our base, Pythas would find a way to expose Dukat to a numbing drug that would enable us to abduct him and bring him back to the house. With the help of the enhancer I would have until the middle of the next morning to complete my interrogation and extract sufficient damning intelligence before I returned him to a specified area. During the interrogation, Pythas would return to the compound and organize a search team. It would be determined that the old man had gone to relieve himself away from the campsite after dark and been attacked by a poisonous plaktar.Delirious, he had wandered even farther away, until he’d passed out in the designated spot. When he would return to consciousness he would never remember what had happened to him.

“As you can see, the plaktarhas a flatter body and longer legs than the tortubial.” Pythas pointed out the differences on his own carefully detailed drawings. “It’s very easy to confuse the two . . . and potentially deadly if you do. One lick of the plaktar’s tongue, depending on the amount of toxin released. . . .” It was another late night, and the information was beginning to bounce off of my skull.

“Please, Pythas, tell me it’s not necessary to know as much as you do,” I begged.

“It is. This is not the Mekar, Elim. And it’s not Cardassia City. You have no idea what’s in that forest. Whether you trek for a week or carry an old man a short distance. . . .” Pythas was merciless. He was determined to teach me in days what it had taken months for him to assimilate about the forest and its denizens.

On the eve of the celebration of Gul Minok’s victory over the Samurian invaders, which traditionally ushers in the beginning of the longest Cardassian holiday period, Pythas organized the equipment in preparation for the overnight trek with Dukat. He handed me a small vial filled with greenish liquid.

“I think it best if you kept this.” I nodded and took the vial.

“If they do an analysis . . . ?” I started to ask.

“It’s a synthetic that’ll match the plaktar’s toxin,” he answered as he tied off the last pack. “Anything else?” he asked.

“No,” I assured him. I could see that he wasn’t altogether convinced.

“It’s important that you cover all tracks between the base and where Dukat will be discovered. And make sure you arrive at the campsite before dark. . . .”

“Pythas, we’ve been over this how many times? I’m no longer a probe.” Perhaps it was because he was accustomed to working by himself, but his incessant repetition of details led me to believe that he could never completely trust others. Either that or he was the most compulsive person I had ever known.

“Good luck,” he said as he lifted the packs. His wiry strength was always a surprise.

“And to you, Pythas,” I replied.

“Who are you?” The old man’s eyes snapped open and immediately focused on me. Either the antidote produced this kind of sudden reaction or Dukat possessed a great ability to recover his self‑control. I suspected the latter. Everything had gone according to plan. I arrived at the campsite shortly after Pythas and Dukat–just before nightfall. Dukat was eager to explore the immediate vicinity; he was energized by the day’s exertion and by being in a place he clearly loved. Pythas had a difficult time convincing him there wasn’t enough light and that the forest was too dangerous after dark.

“The time could be better spent going over possible routes, and getting some rest for an early start,” he reasoned.

Dukat reluctantly agreed, and after they spent an interminable amount of time going over topographical diagrams, and Pythas had patiently answered Dukat’s unending questions (the old man’s reputation as a brilliant military strategist indeed had merit), they finally settled into their camp shells. There was another interminable wait for some sign that Dukat had fallen asleep. Finally, a muttering snore set Pythas and me into action. He moved like a shadow to Dukat’s shell, raised the side panel and applied the “plaktartoxin” to the back of his right hand. All of this happened without a sound. As Pythas moved back to his shell to dress, Dukat grunted.

“What’s this on my hand?” he demanded.

Pythas and I froze in our tracks. Could he somehow be resistant to the drug? We waited in tense silence until we heard the long sigh of a body surrendering to a point just before death. Immediately we were mobilized. According to our plan, I attached Dukat to an infantry sling and shifted his weight to the top of my back across my shoulders. Thankfully, he was a thin, wiry man. I carried him in the direction that a later investigation would determine was the route he took when he awoke in the middle of the night to relieve himself and lost his way trying to get back to camp. Pythas laid the tracks of his own search route and we rejoined at the place Dukat would later be “discovered.” From there it was a relatively short distance to our base.