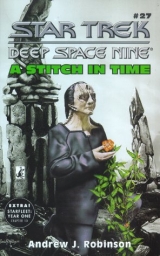

Текст книги "A Stitch in Time "

Автор книги: Andrew Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

After I left the campsite with Dukat, I panicked when I found myself alone in the forest at night. The blackness was so thick I felt like I had been swallowed by a huge beast. Dukat’s inert body and the enveloping foliage and humidity made it difficult to breathe. I had to stop and allow my body and eyes to adjust. Slowly the illuminating marks we had previously established to determine my route began to appear, and I made my tentative way, alerting my senses to be aware of those nocturnal creatures looking for prey. Pythas had taken me into the forest many times during daytime, but it was a different world at night. Every sound, every unexpected touch of a branch or ground creeper stopped my heart. The soft, canopied light that made this world so benign and life‑enhancing during the day was transformed into a killing ground of competing predators, and those of us who relied on a highly developed sense of sight were the prey.

“Are you all right?” It was Pythas, but I couldn’t see him.

“Yes,” I lied. I wanted to weep for happiness that I had found him.

“This way.” I moved in the direction of his voice, and just as I wondered how I would follow him, I noticed that he had placed an illuminating mark on his back. At that moment I truly appreciated his obsession with detail. After a tense but steady march, we came to a trail that took us up along a steep ridge. It was a hard climb, but at one point the forest discernibly thinned out and I felt I could breathe again. Even though my body ached with the strain of carrying Dukat to the top, I was relieved that I was no longer being slapped in the face by malevolent vegetation. Once we reached the top of the promontory, it was a short distance to the house.

“Who I am is not important,” I said as I raised the level of the enhancer. “It’s all a dream and as soon as you answer my questions you’ll wake up and return to your beloved forest.”

It was an advantage, I realized, to have connected him before he regained consciousness. Along with the drug and the light containment field, the suggestion of a dream reality was more threatening to a soldier like Dukat than the familiar context of a hostile interrogation. He sat on a chair with a low back in the middle of an intense cone of light while I remained in the outer dark. His squinting eyes told me that it was difficult for him to see me with any clarity. But his eyes also revealed that he would match the power of his mind with anyone who dared. My best chance with such an experienced and proud adversary was to press my advantage.

“PROCAL DUKAT!” I screamed harshly. He winced and tried to follow me as I receded deeper into the darkness of the room and moved around behind him. His head stopped and snapped to the other side where the containment field also prevented him from turning around to follow me.

“Why did you come here?” I whispered. He tried to shift the weight of his body to stand up and when he realized that he couldn’t, that even the range of his arm movement was limited, he rested his hands in his lap and tried to move into a deep relaxation. In a way it was touching: the old man reverting to the mind control exercises he had learned as a child. I remained still and let the silence extend as I very gradually raised the level of his subliminal anxiety.

“Why was it necessary?” I asked softly.

The silence continued to the point where I had to fight my own impatience. Usually the effectiveness of an interrogation is assured by its sense of timelessness; the maddening possibility that it could go on forever. In this case I was acutely aware that we had to finish by first light when Pythas would have to contact the compound and inform the others of Dukat’s “disappearance.” And yet I had to wait for his response, for some kind of reaction, before I could continue. To force the procedure would only betray my limitations. His breathing had a maddening regularity, and I wasn’t even sure if he was still conscious. I had modulated the enhancer to the upper end of level three, far past the point of no reaction. I wondered if I had attached the filament at the base of his skull correctly.

Suddenly he caught his breath in a ragged gasp that sounded like fear. His body shivered violently, and he held his breath longer than I thought possible. Whatever he was experiencing was terrifying and only his bedrock discipline enabled him to contain it. To admit that fear would have any effect on him was the equivalent of an act of cowardice to a man like him, and I began to suspect that he would literally go mad or die before he’d give me the cue I needed.

“Get inside! Get inside their appendages!” he yelled. “It’s your only chance! You’re going to die–at least die with honor not running away with your backs exposed to their death and ridicule–get inside! Use your hands, your teeth whatever is left is nothing but the last knowing that you died not running like gutted cowards but get inside!” he babbled on one long breath, his face turning red with the effort to control a horror that was uncontrollable. He began to cough and flecks of blood appeared on his lips. “Get inside! Embrace them your lives are not important nobody cares if you live but how you die in the face. . . .” His coughing turned to gagging and choking. He was apoplectic, and tears began to appear. His rage was impotent, and he knew it. He was crying like a little boy whose tantrum was having no effect whatsoever on the outside world. “You cowardly bastards!” he sobbed in a hoarse whisper. His voice was going. “Why won’t you die like men?”

I made the decision to modulate down to the lowest level. I knew the risk I was taking–this might give him the respite he needed to outlast the night–but his threshold was high, and he was perilously close to snapping into insanity or worse. I had to reinsert myself in his process somehow. He would try to match his will with anything I imposed from the outside and fight to the death; I had to become involved, even at the risk of imprinting my identity on his memory. I moved back around into his purview. His eyes were closed, his body clenched as if trapped by the horror of his last image. I came to the edge of the cone of light.

“Why are you frightening me like this? What have I ever done to you?” I asked simply.

He opened his eyes and squinted at me. “You.” Was there recognition?

“Yes, it’s me.” I squatted so that I was at eye level. I tried to soften myself, round off all the sharp edges. “Why are we here? Why have you brought me? I was asleep and safe.”

“There is no safety. You saw them!” he whispered fiercely, his eyes burning with his vision. “We can never sleep. How many times have I warned you? They even invade our dreams and we have to fight them there.” He was feverish, but there was definitely a look of recognition. I had a sudden intuition.

“But what can we do?” I asked like a child. “We’re asleep. How can we defend our dreams?” The clenched muscles of his face began to slowly give way to a smile. I was right.

“Tell me, Father. Please.” A hint of the real son’s overenunciated and ponderous diction began to creep into my voice. I even tried to lengthen my neck. I was summoning up the image of Dukat’s son as much as I could from just that one meeting on Romulus.

“You have to be strong on every level. Cowardice is like a disease and these people will infect you any way they can. Look what happened at Kobixine. They said negotiate with the arachnids. I said no.” The voice was harsh, whispered, but he was going to communicate at any cost. “We have the advantage. Exterminate them. That’s what they want to do to us. We’re outnumbered, but we have the element of surprise on our side. We have to use it!” The old man began to cough again and flecks of blood and spittle flew into my face. “Gul Karn caved in. He became infected. We lost our advantage and the arachnids slaughtered us.” The memory was fresh and bitter. “That’s why Karn had to die, son. That’s why we need the Brotherhood. They must not be allowed to infect us!”

I began to breather easier. Now we were getting to the crux. “Who are they, Father? Tell me so I can recognize them,” I pleaded.

“You know them!” I could feel the heat of the old man’s anger. “How many times have I warned you? Only fools don’t listen!”

“I’m sorry, Father,” I whispered.

“They’re the same people who now want to kiss the Federation’s ass and sign treaties that turn us all into women. Again, we have the advantage and the civilians and the traitors are pissing it away.” His disgust was corrosive. “We have two implacable enemies, son. How are we going to fight them if we turn our warriors into women? That’s what the Assembly wants to do!”

“The Federation . . . yes,” I said. “They only understand power . . .”

“And the Klingons, boy! Don’t forget them!” he commanded as if they were surrounding us. “They understand power, too, and if they think we’d rather talk than die. . . .” Dukat trailed off.

“I won’t forget them, Father.” I started to modulate the enhancer up. I didn’t want to lose him. His eyes widened with a new thought.

“Did you go to Romulus?” he asked.

“Yes, I did. With Barkan,” I added.

“He’s good. He’s good, son,” the old man nodded. “But watch him. He’s like his father. If a better deal can be made. . . .” I modulated higher. He was seized by a spasm and his face contorted into a rictus. “That’s what they look like!” he screamed. “That’s what they really look like when you strip away. . . .” His breath ran out and he began to choke in an attempt to refill his lungs. I chose not to modulate down. “We have to . . . kill them. Carriers . . . they carry the disease. Every one of them. Surround the Assembly . . . let everyone watch so they never forget. Ghemor . . . Lang . . . the guls who stand with them . . . especially the traitors!” Dukat was energized and tried to rise as if he were exhorting his troops. The frustration of not being able to poured into his words.

“The Brotherhood has to move now! The families must take their rightful place. Support the Directorate or die. And no exile! Exile is just deferred treachery. Those who were meant to rule must rule. End these negotiations with the Federation. Use the Romulans to drive the wedge! What did they say?” he suddenly asked me. “Will they move with us against the Klingons?”

“They said . . . yes. Yes, they will.” I didn’t know if this was the right answer, but I had to keep moving. Dawn was breaking.

“Good. Cripple the Klingons and then we can move against the disease itself.”

“The Federation,” I said.

“Yes, boy. The Federation. But first we have to root it out here . . . we have to purify Cardassia before. . . .” His breathing was becoming increasingly tortured, and his voice was reduced to a painful rasp. I was afraid that the sustained exertion would seriously injure him to a point that aroused suspicions. I shut the enhancer down. His eyes closed and his ashen face relaxed. I left the containment field in place and stepped outside to clear my head. No matter how objective I tried to remain, I could never remain totally unaffected by another man’s horror. Fear was a contagious disease. It was nearly full light now, and I knew that I had little time to bring him back before the others arrived.

When I stepped back inside he appeared to be sleeping. I turned off the containment field and hid the enhancer and the recording devices which would document Dukat’s “confession.” I prepared a lighter dose of the plaktartoxin and reattached the sling to my body. When I turned back I was shocked to see him standing and looking at me with a clear and level expression.

Suddenly he attacked me, and as I stumbled back to avoid his furious rush I nearly spilled the toxin on myself. I slammed him into the wall and he sagged. He had no reserves with which to maintain his advantage. I twisted his right arm around to his back and administered the toxin. As I was attaching him to the sling he turned his head and faced me.

“Who are you?” he asked for the second time, fighting against the toxin’s effect. This was one tough old warrior.

“Your worst nightmare,” I replied.

“Ah,” he croaked. “Then Tain sent you.” He gave me one last murderous look before he lost consciousness. In a flash I realized that I hadn’t got him to name any members of the Brotherhood. But I was more concerned about his associating me with Enabran Tain.

19

Entry:

Hands yanked and ripped the clothes off my body. I was unable to make any effort to stop them and couldn’t make out their faces.

“Strip him completely. He’s dead.” It was Doctor Bashir’s voice. But I’m not dead, I wanted to say. I couldn’t form the words to voice them. I was absolutely helpless as they lifted my naked body and threw me into the deep pit on top of the other bodies.

“Ah, Elim,” the body next to mine said. “You, too.” It was Tain.

“Sooner or later we all end up here,” the body beneath me observed. It was Tolan. All the bodies in the pit were murmuring.

“But we’re alive,” I protested above the babbling drone. “What are we doing in here?”

“This is the final strategem, Ten Lubak.” It was Calyx. “If you can master this one, you’ve found your place.”

“But this is horrible. This can’t be my place. How can I master this?” I pleaded.

“This isyour place,” Lokar’s voice informed me. “And you must never forget it.”

“Just tread lightly, Elim. Use the silences,” Pythas’s voice advised me. I tried to move so I could see him, but I couldn’t.

“Accept, Elim,” Mila told me. “Stop fighting who you are and then you can move ahead.”

“But why? Why are we here? And where’s Palandine?” Before anyone could answer I felt a load of soil and rocks fall on my body.

“That’s the last one,” Doctor Bashir called above me. “Cover them up and seal off the pit. For the good of the quadrant they must never be allowed to return.”

“But why?” I cried. “Calyx, how do I master this?” My questions were answered by the falling soil and the murmuring babble. “How? Tell me! How?”

I pushed myself away from the desk, bathed in sweat and gasping for breath. I stood up and looked around the room. Slowly, I came back to the station and the night silence. I had fallen asleep working at the desk. I rubbed my head where it had rested fitfully against the hard surface. This was probably my last night on the station. Perhaps forever. I had so much work I wanted to complete. It was late, but I punched a code on the station comm.

The voice cleared a passage in the throat to be able to speak. It was exactly what I couldn’t do in the dream. “Yes?” the Doctor asked.

“Doctor, forgive me, but I need to see you,” I said as calmly as I could.

“Garak?”

“I do apologize, but it’s important.”

“What’s wrong?” the Doctor asked, trying to gauge the level of importance.

“It’s not a medical emergency. Please, I realize this is an imposition.” There was a silence and I heard another voice in the background. Ezri Dax. A muffled conversation. The Doctor cleared his throat again.

“I’ll be right over,” he said.

“Thank you, Doctor.” I turned to the window, and the eternal night of space. My beloved stars. Only a nightmare as terrible as this could make me so grateful to be alive on this station. How ironic that I would be leaving it in a few hours.

“It’s the anxiety of going back to Cardassia,” the Doctor assured me. “And it’s a very dangerous mission. Does one ever become inured to the possibility of death?” the Doctor asked.

“Not really,” I answered as I served the Tarkalian tea. “If we lose our fear of death, we lose an important ally.”

“I don’t know, Garak.” The Doctor sipped his tea. “Perhaps you should talk to Ezri about this. I don’t know how much help I can be.”

“Ezri, with all due respect, wasn’t in the dream.”

“Neither was I,” the Doctor replied.

“On the contrary, my friend, you were.” He gave me his puzzled look, which wrinkled his brow. I was always amazed at how deep the furrows were for one so young.

“I trust you don’t mean that literally.”

“You were in my dream,” I maintained.

“Garak, you can’t believe. . . . Look here.” The Doctor took a deep breath. “My . . . persona . . . my symbolic representation was in your dream to . . . serve a purpose devised by your subconscious mind to satisfy some . . . need. It had nothing to do with me other than how your psyche used me . . . the way a . . . play‑wright uses a character.” The Doctor paused and shook his head. The idea of his participation in my dream had ruffled his science. “This area has always been a great mystery. If I had a dream about . . . Hippocrates, you can’t believe that this ancient Greek healer actually showed up,” he challenged.

“We exist on many levels at the same time, Doctor. This level. . . .” I gestured to the room and its objects. “. . . the space/time continuum, I believe you call it, is perhaps the narrowest and least dimensional of all. But it’s the one in which we choose to relate to each other as corporeal beings in a defined material space measured by units of time. It serves a purpose, yes, but it’s a purpose that’s been determined by our interaction on otherlevels, deeper and more complex than this one.”

“What’s the purpose of this one then?” he asked impatiently.

“To consummate the agenda created by our more dimensional selves!” A passion had crept into my voice, and the Doctor just looked at me.

“ ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’ ” he quoted.

“Who’s that?” I asked.

“Shakespeare,” the Doctor replied.

“Hmmh.” I nodded in agreement, surprised that for once the author of the politically misguided Julius Caesarmade sense.

“I’ve never heard you talk like this before,” he said. “ I had no idea Cardassians held such ideas.”

“Most don’t. But we once did.”

“So you’re saying . . . what? That this level is the concrete manifestation of . . .” he stopped.

“Of who we are, Doctor. Our being. Human being. Cardassian being. But we have become these beings– arebecoming, always in the processof becoming–on these other dimensional levels that are not limited by the measures of time and space. And the great determining factor of our becoming is relationship. Unrelated, I become unrelated. Alienated. Opposed, I become an antagonist. Unified, I become integrated. A functioning member of the whole.” The Doctor was thoughtful; his previous agitation had dissolved.

“You’re a scientist, Doctor. You have a deep understanding of thislevel. I don’t mean just the mechanics. You understand about relationship, the laws that attract and repel, the combinations that nurture and poison. Health and disease. Integrity and breakdown.”

“In your dream,” he said, “I presided over the burial of yourself and the people you were most intimately related to. Why?”

“You said, ‘for the good of the quadrant . . . they must never be allowed to return.’ Why would you say that?” I asked.

“I can only think that. . . .” He stopped and shook his head. “I’m sorry, Garak. This is not easy for me. I still can’t help thinking this was yourdream. Even if I was invited . . . you were the playwright.”

“Yes, but put yourself in that part. Why would you bury these people and cover up the pit?” The Doctor looked at me in frustration. “Please. Indulge me. It’s vital that I have your answer.”

“If you and the others were carriers of some disease,” he shrugged. “In our fourteenth century on Earth there was a terrible plague, the Black Plague, which wiped out half of Europe’s population. People believed that the dead bodies had to be destroyed, burned . . . buried . . . because it was the only way to prevent the spread of the disease. . . .”

My comm sounded. “Garak.” It was Kira.

“Yes, Commander.”

“Can you be ready to leave at oh‑seven‑hundred hours?”

I sighed. It was less than an hour, but I had no choice.

“Certainly.”

“See you in Airlock 11. Pack lightly.”

“Just my hygiene kit and a change of undergarments,” I said lightly. We clicked off. The Doctor was studying me with an interest in his face I hadn’t seen in years.

“Well? Is it the Black Plague, Doctor? Or just the ramblings of an old spy on the eve of battle?”

“You’re an amazing man, Garak.”

“And my gratitude to you can never be adequately expressed. But I shall try,” I promised.

“Please. What have I done?” he asked genuinely.

“That time you extended yourself so generously and found a way to remove the wire from my brain without killing me . . .”

“I would have done that for anyone,” the Doctor interrupted.

“I’m sure that’s true, but that’s not what I mean. All during the time the device was deteriorating, I was convinced I was going to die.”

“You were even resigned to it,” he reminded me.

“I was also convinced that it was all a dream, and I kept asking myself what you were doing there.”

The Doctor was puzzled. “But what you just told me, that our dreams are just another way we relate . . . ?”

“I had forgotten. That point of my life was perhaps the lowest. I had forgotten many things. When I ‘woke up’ and realized that because of you I was going to live–at that moment, I began to recollect some valuable information.”

“About dreams?” he asked.

“Yes. But specifically about relationships, and how they set the course of our lives. You not only ‘saved’ my life, you also made it possible for me to live it.” The Doctor’s face darkened.

“What is it, Doctor?”

“The time I wounded you in that holosuite program. . . .”

“Yes,” I prompted expectantly.

“I never apologized for my action.”

“And you must neverapologize!” I urged.

“Please, Garak. This is not the time to give me a lesson on how to behave like a hardened spy. . . .”

“No, no, no. On the contrary, when you shot me, my dear friend, that was the next step in my process of remembering. I was going to sacrifice the others, the people you considered your friends, because that was the only way I could be sure to save myself. You opposed me. Indeed, you would have killed me if necessary.”

“I’m sure it would never have gotten to that point,” the Doctor muttered.

“You would have killed me,” I repeated. “For the greater good.” The clichй suddenly had another meaning for both of us. “This is my last trip to Cardassia. I’m not returning. You were in the dream for a very specific reason. Once again, you helped me remember. Thank you, Julian.” I put my hand on his shoulder.

“You’re welcome,” he smiled warmly. “And by the way. It wasn’t the dead bodies that carried the disease. It was later determined that it was the rats feeding on the bodies who were the transmitters.”

“Then I guess we’ll go to Cardassia and look for the rats,” I said.

“Be careful, Garak. And look after my hot‑headed friend, will you?”

“Don’t worry. We’ll look after each other,” I answered him. He moved to the door. “Did you really have a dream about Hippocrates?” I asked.

“Yes. Actually I did.”

“Why am I not surprised?” I replied.

Kira was waiting in front of the airlock when I turned the corner.

“Odo’s on his way. How are you feeling?” she asked.

“I’ve never been better, Commander,” I replied with fervor. Kira gave me a long look.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen you so enthusiastic, Garak.”

“I’ve finally remembered why I’m here.”

20

Entry:

“Let’s walk, Elim. It’s a lovely day.” Tain was waiting for me in front of the Assembly building.

“As you wish,” I agreed with pleasure and mild surprise. Over the years we rarely met outside his office; only an emergency or drastic change of plan would alter the routine. Now as we walked through the late morning sun and pedestrians at a leisurely pace I experienced a connection to the surrounding bustle and energy in a way that felt almost normal. A father and his son taking a stroll. Tain was heavier, and I could hear his breathing labor with the effort. He’s an old man, I thought. He’s mortal. I’d never thought about Tain in this way, and I became protective as we approached an aggressive knot of pedestrians at the edge of the Coranum Sector. One man was about to run Tain down when I intercepted his path and bumped him to the side. I ignored his challenge as we continued.

“Yes, Elim. I’m getting old.” It wasn’t the first time he picked up my thoughts; this was how our conversations usually went. “It’ll happen to you, too. You’ll wake up one day and realize that you have just enough energy.”

“For what?” I asked. I was alerted.

“To leave your affairs in order,” he replied. “But you have to start thinking about these things long before that day arrives.” Behind the hooded half‑smile was the steely focus that always challenged me to rise to the occasion.

“You’re leaving the Order,” I said.

“I am.”

“Where are you going?” I tried to control the sudden sense of dislocation that had usurped my newly found connection to the community.

“To the Arawak Colony.” Of course. His beloved mountains in Rogarin Province.

“Is Mila going with you?” I asked.

“She is.” I struggled to put all the forming questions into some kind of order. I wasn’t paying attention to our surroundings, and it was only when Tain stopped that I looked around and realized where we were.

“There is the matter of succession, Elim. The Order has managed to steer a course that’s been consonant with Cardassian security. The new leadership must maintain that course.” I didn’t know if it was the uncertainty about my own future or the fact that we were standing in the grounds where Palandine and I had spent so much of our time together, but I felt the inevitability of some kind of final reckoning. This was so typical of his manipulation. Just moments ago I was feeling protective of this benign old man, my father. And now . . . the irony filled my mouth with a bitter taste.

“Yes, you see. It’s a problem,” he nodded. “Two problems, actually. The less serious is that you’ve been connected to the incident with Procal Dukat. But we expected that he might retain enough memory of the interrogation. What was not expected was Barkan Lokar’s recognition. While there’s nothing they can prove, still, you’ve made some powerful enemies. Lokar has determined who you work for and he and the young Dukat now have you in their sights. Of course our stature is measured by the enemies we make, and that would be reason enough to allow you to succeed me,” he said in a gentle, almost paternal tone that was keeping me off balance. He moved to the covered seating area, where the sun filtered through the old vegetation. I had never been here with anyone but Palandine. With a long sigh he settled into a patch of sunlight on the low bench.

“This is a beautiful place. I can understand why it’s an ideal rendezvous,” he observed.

“I always expected that you’d find out,” I said.

“But what were you thinking? Not of the long term, certainly. And it’s not just anywoman. She’s Lokar’s wife. Sooner or later he’s going to find out. You know that, don’t you?” he asked with a sharp edge.

“Yes,” I answered. The benign mask was slipping, and I began to see the depth of his anger.

“And when he does, your powerful enemy now becomes an implacable one. He won’t rest until he has destroyed every trace of you.” He was spitting his words at me. “What are you going to do?” he demanded.

“I don’t know,” I admitted with tightly wound control.

“You don’t know!” he repeated with a disgust I hadn’t heard since I was a boy and failed to record all the details of one of our walks. “And I’m supposed to pass my life’s work on to someone who can’t think beyond his lust?”

“It’s not lust,” I argued.

“Sentimentality,” he hissed. “Even worse. You jeopardize our mission, the security of our people because of pathetic sentiments. And all this while, instead of giving up your life to the work, hardening yourself into a leader who could inspire others and expand the vision, you’re playing out Hebitian fantasies with another man’s wife!”

“Yes. Just like Tolan!” I exploded. “Perhaps he wasmy real father after all.”

Tain rose like a man many years younger and grabbed my shoulder in a powerful grip. His anger was now a murderous fury and it was all I could do to hold my stance against the pain of his grip. His cold eyes told me I had betrayed him. Worse, I had failed him. He let go of my shoulder and turned away from me. My entire body trembled. When he turned back he had regained his composure.

“You’ve been returned to probe status. You will be given a period of time to prove whether you have anything of value to contribute to the organization. This, of course, is contingent on your never seeing the woman again and immediately setting into motion a plan to eliminate Barkan Lokar. A plan that will not implicate the Order. From now on you will report to Corbin Entek.” He could have been speaking into a comm chip.

“And who will be succeeding you?” I asked.

“He already has. I leave for Arawak tonight.”

“Who is he?” I persisted.

“Pythas Lok.” He watched me for a moment. His mask was back in place. “Goodbye, Elim.” He turned and walked away.

As I watched him leave, I felt completely empty and wondered how I could feel such emptiness. This sudden, wrenching reversal of fortune . . . everything changed beyond recognition. . . . And yet . . . there was no anger, no self‑pity . . . no fear. Only release. Release from the secrets. Release from the limbo where, ever since I was a boy, I had been trapped between imposed obligations and feelings of mysterious longing mixed with shame. I felt empty . . . and free.

I had to see her again.

“I was expecting you,” Mila said when the door opened. I followed her inside, and instead of the customary trip down to the basement she took me to the large central room, which was filled with stacks of packing bins.

“I’m afraid we’re not leaving you much,” she said. “The furnishings have already been taken away.”

“I wasn’t expecting anything.” I tried to keep all irony out of my tone.

“It’s your choice, Elim.” Her voice was just as neutral. “The house is yours to live in.”

“I assumed Pythas would be moving in.”

“The house belongs to Enabran, not to the Order,” she explained. “Under the circumstances you have the choice to live here.”

“Do you know the circumstances . . . Mila?”